Who will ascend to heaven, mistress mine, to fetch me back my lost wits? (Orlando furioso, XXXV.2)

Before we get into Orlando, I did want to assure some of you that I didn’t forget about giving updates about the release of my next novel, Daughter of Scorpions. I would personally love to have a concrete pub date for you all by this point, but unfortunately the course of publishing, much like true love, did never run smoothly. The group I use for my cover designs was bought out last year by, of all people, my digital publisher, and while that portents a greatly streamlined process for someone like me who uses both in the future, the transition—due to a variety of extenuating circumstances—has been extremely rocky. What that means for me is that it has ground the process of getting covers made down to a crawl; something that once took maybe three weeks total has been a months-long journey. While, as I showed you all in January, my front cover is ready to go, we’re still trying to get the spine and back cover finished (I can’t do both covers simultaneously because you need a finalized, formatted page count to correctly map the spine thickness).

What this means for you, dear readers, is while I had hoped for a March/April release, since I will still have to do a paperback proofread once we get the back cover files finalized, we are more realistically looking at a May/June timeline at this point. As I’ve said before, the best thing about self-publishing is that you have control over all parts of your book’s production, but the worst thing is that you have control over all parts of your book’s production. I will continue to keep you posted.

[IRL people in the last eight months who have foolishly asked me about when the next book is coming out after listening to my explanation…]

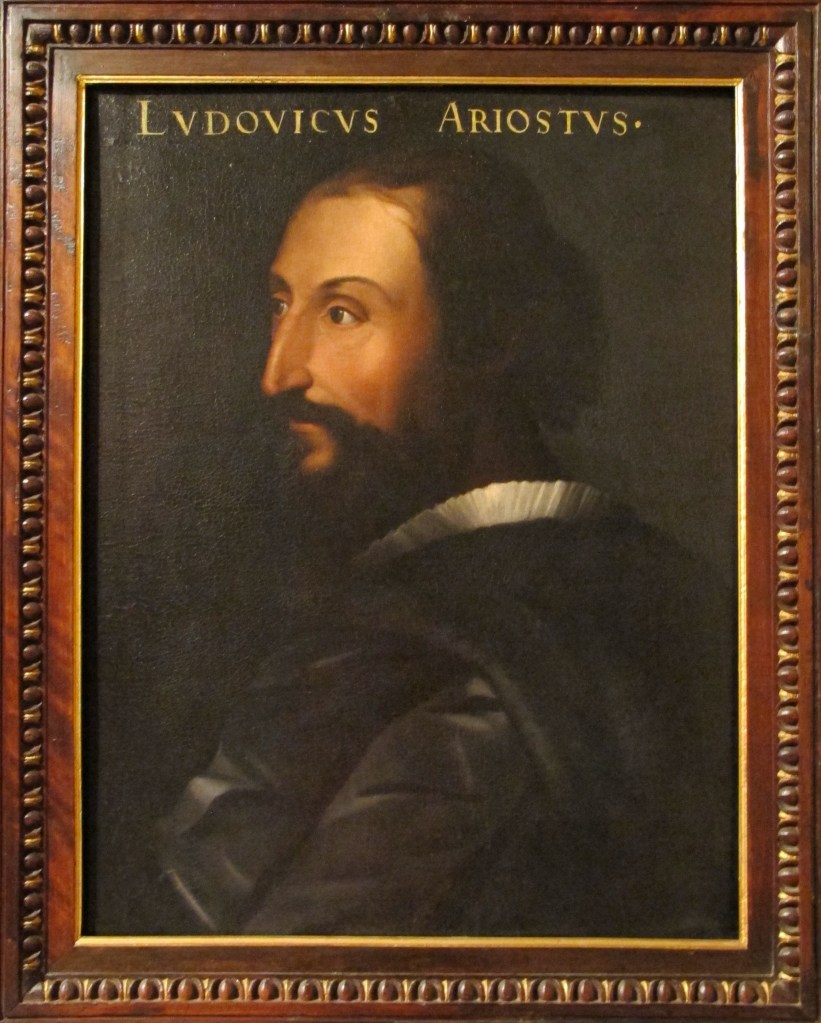

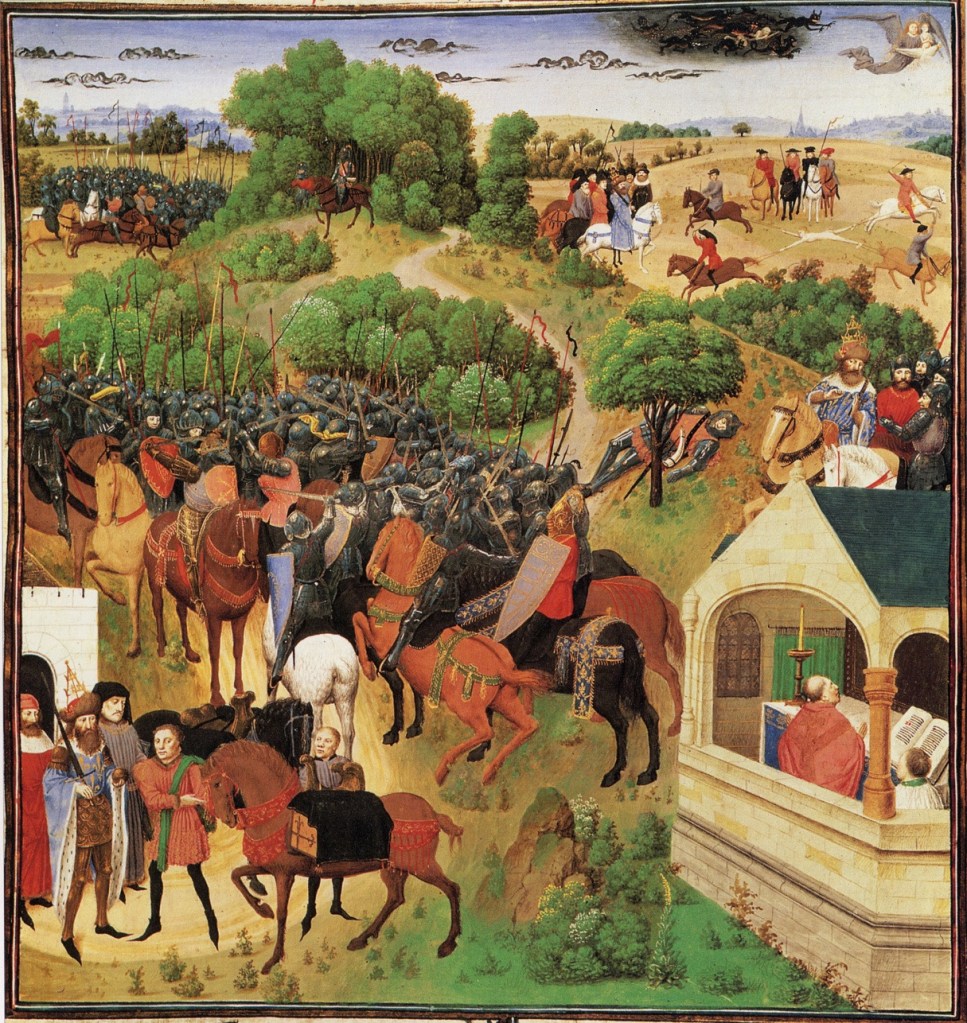

In the meantime, we’ll distract ourselves with another installment of medievalish Lit Crit, and look at the influential post-medieval poem, Orlando furioso. Written and revised over the course of nearly thirty years by Italian diplomat and court poet Ludovico Ariosto (1474-1533), Orlando would synthesize a whole swath of medieval European chason poetry and mythology, and adapt it for an emerging Renaissance audience hungry for an idealized chivalric past. Not only would Orlando preserve a compendium of continental and Arthurian mythos for a new generation, the poem itself would spawn dozens of imitators across Europe and basically create a whole subgenre of Renaissance-era stories about knights, their ladies, and their crazy adventures.

Despite Ariosto’s complaints that his patrons, the Italian House of Este, the dukes of Ferrara, weren’t supportive enough of his magnum opus, it’s actually hard to overstate how influential Orlando was to the wider European Renaissance literary scene. When I was reading through its plot, essentially a long series of thinly connected vignettes about a sprawling cast of noble lords and ladies engaging in chivalric quests, I literally did the meme of “Woman who has only read Mary Wroth’s Urania: ‘I’m getting serious Urania vibes from this.’” But of course, that’s getting the causation wrong. When we talked about Urania (1621) a couple of years ago, I mentioned how it was influenced by Orlando, but I think even I was unprepared for how much of Urania is essentially a fan fiction reworking of Orlando. Wroth uses (mostly) original characters based on her own English court acquaintances, but the structure is pure Orlando—and imagine my surprise when Wroth’s mysterious priestess-enchantress Melissea popped up in Ludovico Ariosto’s story as a virtually identical character named Melissa.

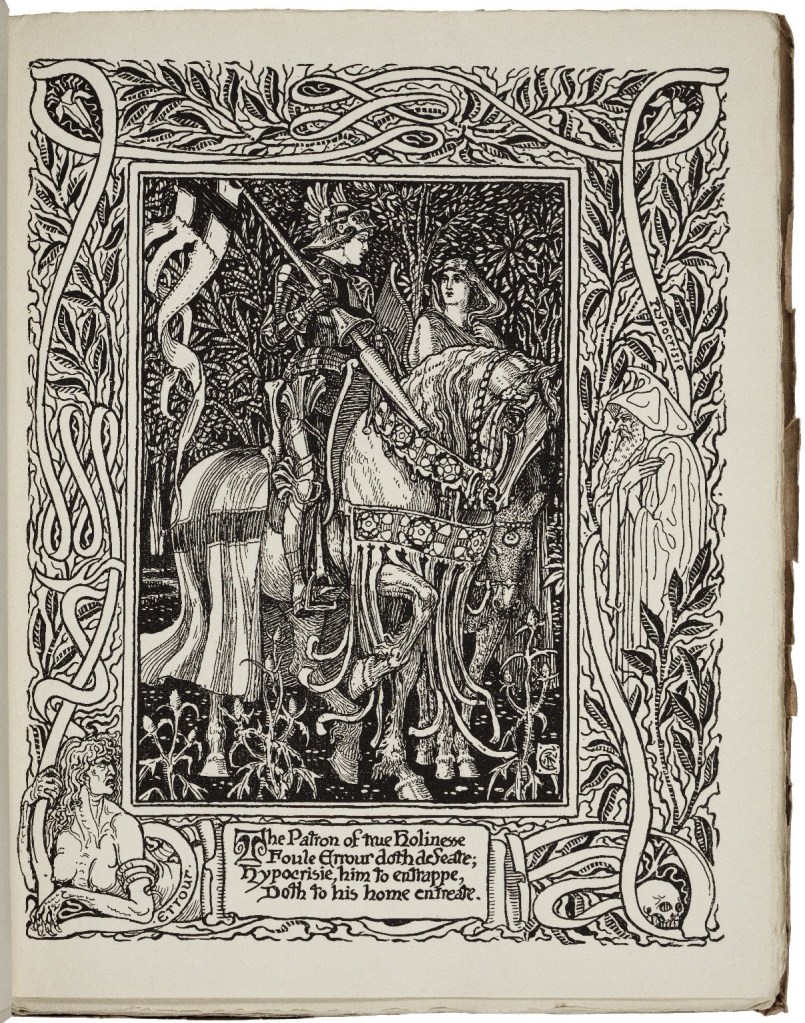

But as Urania remains culturally obscure to people outside of this blogosphere, the English prose poem mostly likely to be cited as a direct descendant of Orlando is Edmund Spenser’s The Faerie Queene (c. 1590). The Faerie Queene leans more heavily on allegory than either Orlando or Urania, but again, its structure is directly cribbed from the former, and its stock characters are even more similar than Urania’s. Right down to the noble maiden who fights like a knight. But as Urania is obscure and The Faerie Queene is usually deemed too tedious by the general reading public, the mostly likely Orlando-adjacent literary work you’ve encountered is Shakespeare’s play, Much Ado About Nothing (1598/9). Much Ado is less obviously an Orlando clone, but as it takes part of its mistaken identity plot either directly from episodes in Orlando, or from The Faerie Queene, it is directly engaging in the long line of literary Telephone that stretches from Orlando directly through to modern authors like Salmon Rushdie and Jorges Luis Borges.

But this party line spools both ways, as Ariosto himself is cribbing on earlier works, as was usually the case in medieval and directly post-medieval literature, where, as we’ve discussed, there was less emphasis on originality and concrete authorship. Many of the characters in Orlando furioso are pulled directly from Frankish and Arthurian folklore—a fact that becomes much more obvious when you realize that “Orlando” is simply the Italian cognate of Roland.

[Ooooooooooh…]

So yeah, Orlando furioso is about the medieval French hero Roland from the 11th century La Chanson de Roland, though because (spoilers) Roland dies in the original poem, Orlando furioso represents a nebulous prequel that takes place by necessity in some indeterminate earlier time. But as with a lot of these medieval and post-medieval stories, there are layers to the ostensible plagiarism going on here, because Ariosto is not only writing a Roland prequel, he’s also writing a sequel to another Italian’s attempt at a Roland prequel: Matteo Boiardo’s unfinished prose poem, Orlando innamorato (c. 1495). Potentially the hardest part about reading Orlando furioso is that it assumes you’ve read Orlando innamorato, and as a result picks up the story mid-stream.

So what happened in Orlando innamorato (Orlando in Love)? Briefly, Angelica, the princess of Cathay and her brother come to a Franco-Muslim tournament being held in France by the emperor Charlemagne, where the brother challenges all the competing knights to a joust, with Angelica as the prize if he is defeated. The brother is killed by the Saracen knight Ferraguto, who actually had lost his joust, but Angelica flees before he can claim her, with most of the other knights—presumably feeling that she is now fair game—in pursuit, led by Charlemagne’s best paladins, cousins Orlando and Rinaldo. There’s a complicated love plot where Angelica accidentally drinks from an enchanted spring that makes her fall in love with Rinaldo, while he does likewise at a spring that makes her repulsive to him. Orlando frees Angelica from capture, but she escapes him. Orlando and Rinaldo are pushed by love and honor to duel each other to the death over this whole situation, but their feud is interrupted by the invasion of a coalition Saracen army invading from Africa, which is largely where the poem breaks off. In the background of all of this, Boiardo, also in service to the ducal Estes, is weaving in the adventures of a Saracen knight, Ruggiero, and a Christian maiden knight, Bradamante, who are destined to become the mythical founders of the House of Este.

When Ariosto picks up the narrative in Orlando furioso (The Frenzy of Orlando), Angelica is still on the run from this pack of knightly pursuit, aided by the recovery of a magic ring that renders the owner invisible when it is put in the mouth.

[This would have brought a totally different vibe to LotR]

Somewhere in the interim, she and Rinaldo have swapped magic spring water and now she hates him, while he’s infatuated with her (though just wait until you find out in Canto 42 of 46 that he already has a wife…🙄). Charlemagne is desperately trying to get his best knights to, you know, help him stop the Saracen invasion of France, but Rinaldo and Orlando are too busy chasing Angelica to care. A dozen different side quests and hijinks ensue for them, as well as those of Rinaldo’s sister Bradamante, who’s trying to be reunited with her pagan love Ruggiero, and get him to the church so he can be baptized and marry her.

The title comes from when Orlando learns that Angelica has fallen in love with a random African Saracen knight and both of them have returned to rule Cathay, he completely loses his mind and spends the back end of the poem rampaging butt-naked (yes) through the French countryside indiscriminately killing innocent animals and bystanders. Seriously, there is a big section of the poem where characters bump into each other, and one of them will be like, “I think I saw Orlando running around naked outside of X…” There’s an extended sequence where Orlando takes a guy’s horse, rides it to death, then is so mad at it for dying that he drags the horse behind him for weeks until he finds another guy’s horse to steal. He does this kind of shit until Astolfo, a knight Ruggiero had helped out of a jam earlier flies a damn hippogryph up to the Moon (yes, that Moon) so that St. John the Evangelist can give Astolfo a little vial containing Orlando’s wits to return to him. This shakes Orlando out of his madness as well as his love for Angelica just in time for the Saracen invasion to be repelled, and Ruggiero and Bradamante’s wedding. Everyone lives happily ever after, except for the unrepentant Muslims and all of the people and horses Orlando killed.

[This is where the meme flipped for me and became “Woman who has only read The Water Margin: ‘I’m getting serious Water Margin vibes from this.’”]

The absolute craziest thing about Orlando furioso isn’t its protagonist’s madness, it’s his entitlement. I assumed going in that Orlando’s desire to possess Angelica had some basis in reality—either he had won her in the Innamorato tournament, or she had made some kind of courtly love promises to him that she reneged on (which under the rules of chivalry meant she “owed” him her devotion). But no, in all of the convoluted love triangles, tournament rules, or chivalric conventions, at no time does Angelica have any obligation to entertain his affections. This true for Rinaldo too, but at least there are some magical shenanigans adding to his situation; Orlando doesn’t even have that excuse, and neither any of these other dudes. Honestly, one of the most enjoyable things about the poem as it went on was watching Angelica weasel out of these chuds’ grasps. She depicted as a prototypical “cruel” chivalric mistress, but her only real fault through all of this was perhaps stupidly thinking she could find a decent husband at Charlemagne’s court.

[Obviously since this the Renaissance, Angelica is depicted as a stereotypical blonde waif, but it’s way more entertaining to envision her as a true “Cathay” royal, where she could a Chinese princess, an Indian rani, or a Mongol khātūn, depending on where exactly Ariosto himself believed “Cathay” to be.]

Now, in addition to sticking in his own sucking paeans to his Este patrons (at several points, he does the Virgilian thing where some mystical character will stop the plot cold to show Ruggiero or Bradamante their wonderful descendants), you might have picked up on the other thing Ariosto brings to OG Roland and Boiardo’s earnest chasons is a pinch of irony. Each canto begins with a personal aside to reader (listener in the case of his Este patrons) from Ariosto, some of which are serious commentary on social issues, but many of which are tongue in cheek lamentations about an unnamed cruel mistress of Ariosto’s, who has led him to both to write about a lost chivalric era where ladies were true… while also telling tales about many less chaste and loyal fictional women. Any time he denigrates women in his story, you can be sure that the next canto will start with a profuse apology to the good, noble ladies who no doubt make up his audience who would never behave in such a way. Some scholars see this, along with his valiant female knights Bradamante and Marfisa, as a weak sort of proto-feminism on Ariosto’s part. But as you might expect, an Orlando-esque story like Urania from an actual woman writer more intimately connected to the challenges of post-medieval womanhood is much more successful at any sort of proto-feminism than Ariosto’s less than entirely serious epic.

Similarly to the treatment of women within the poem, it’s hard to see Orlando’s over the top psychosis as anything but an extend joke about the lengths of folly love can drive a person. His hero repeatedly, literally, beating a dead horse is no less silly than a world governed by weird and arbitrary Arthurian magic to an author living in the middle of Renaissance humanism. But this is not to say that Orlando is pure satire as we would think of it. Just as the later Victorians would be, many of the monarchical and aristocratic courts of Renaissance Europe were deeply interested in at least the pageantry and trappings of medieval codes of chivalry and culture. As warfare continued to change over the 16th and 17th century, this period’s kings were possibly even more obsessed with showy tournament jousting than most medieval rulers were, and flowery medieval love poetry was still the standard by which romantic correspondence was conducted. Roland’s epic Thermopylae stance in the original chanson was still a story people wanted to hear enough to spawn fan sequels four hundred years on. Ariosto chose this setting and these characters not because they were necessarily his own preference, but because they would be interesting to his patrons. And he would have gotten even less further with the Estes if they thought he wrote it solely to make fun of them.

Like the medieval works that it was birthed out of, you can’t really come to Orlando looking to fall in love with characters or innovative plotting. What makes it worth the trouble, though, is its place of importance on the road to the modern novel, arguably the link between the medieval prose poem and true attempts at original storytelling style structure. To read Orlando furioso in 2025 is to see that without mad lad Orlando, not only do you not get Britomart, the Redcrosse Knight, or Pamphilia, but you don’t get Beatrice and Benedick, and it has been suggested, you might miss Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader, too. All of literature rests on what came before it, setting rules and prototypes. Modern literature has reached a point where it owes more to Ariosto’s Orlando than it does to the Roland who got the ball rolling, but you can’t have one without the other.

Leave a reply to sopantooth Cancel reply