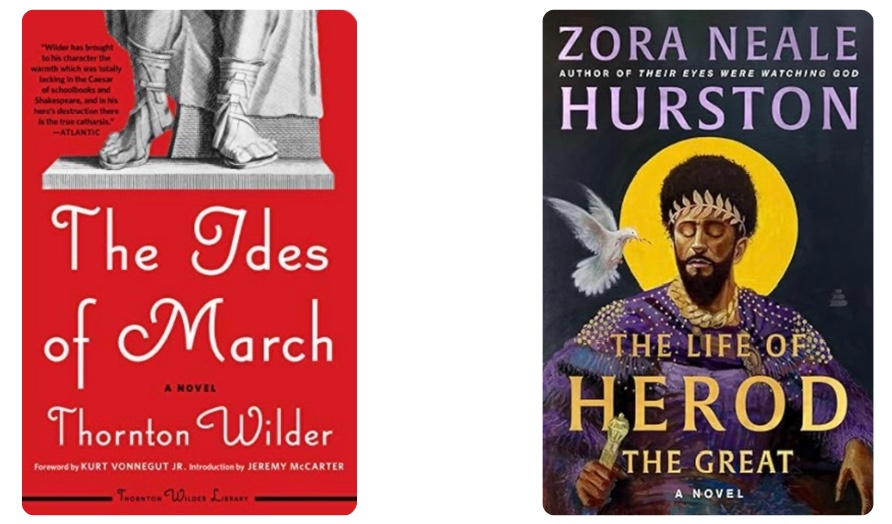

While it’s hard to ever call historical fiction set in the Roman period passé, I do sometimes feel like I’m out here on an island, as it seems most of the current genre zeitgeist is for almost entirely 20th century historical fiction, with a few forays into midcentury Victorian. But as I’m pretty much never on trend anyway, I might as well continue to be myself. Particularly as when one writes about Rome, one is never truly alone. Some of my reading from last month bears this out, as I coincidentally picked up two novels written by classic, American high school reading list authors dealing with the Roman first century pivot moment. The first being Zora Neale Hurston’s unfinished novel, The Life of Herod the Great, published posthumously this year, and Thornton Wilder’s 1948 novel, The Ides of March. Although arguably occupying different parts of the midcentury literary landscape, Hurston and Wilder were contemporaries, and I thought it would interesting to compare these two works for what’s the same, what’s different, and what it might mean.

But first, for the unfamiliar, some quick and dirty context. Zora Neale Hurston (1891-1960) was a writer and scholar, and a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and 30s. Trained as an anthropologist, most of her contemporary impact was as a folklorist, journalist, and documentarian of southern American Black and Afro-Caribbean culture, though modernly, she is primarily remembered as a novelist through her 1937 book, Their Eyes Were Watching God. Influential in Black intellectual circles throughout her life, however, by her death in 1960, she had fallen into poverty and obscurity—so much so that her remains would be buried in an unmarked pauper’s grave. It would take a decade and more before Hurston’s spiritual successors like Alice Walker and Toni Morrison would resurrect her literary legacy and secure her place in the pantheon of Black American writers.

Like Hurston, Thornton Wilder (1897-1975) was also not primarily known as a novelist in his own time, and arguably still is more famous to us as a playwright. Although he would win a Pulitzer for his novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927), Wilder’s most enduring legacy is through his Pulitzer-winning play, Our Town (1938), the behemoth staple of high school drama productions for the next fifty years, and The Matchmaker (1954)—the play that would be adapted into the even more successful musical Hello Dolly! a decade later. If Hurston represented the cool, bohemian fringe of the Harlem Renaissance, Wilder was at the center of the white American literary culture, though his close ties to the expat scene in Paris through friends like Ernest Hemingway and Gertrude Stein mitigated his Yale/Princeton academic background. And like Hurston’s training in anthropology, Wilder had some cross-disciplinary grounding in archeology from a residency at the University of Rome in his twenties, where he first became interested in some of the historical minutiae that would become The Ides of March. Though in sharp contrast to Hurston, Wilder would remain popular and solvent until his death in 1975.

As you can see, especially in Herod’s case, obviously, neither of the works I read are in any way considered the standouts of their respective authors’ oeuvres. Hurston was shopping around drafts of Herod at the time of her death; her editors and publishing contacts, while encouraging, thought the manuscript still needed polishing. And Ides was well-received when it was published in 1948, but it was overshadowed that year by two other instant classics: Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country, and Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead. So at least in this regard, I feel like comparing these two books puts Hurston and Wilder on equal footing, as both are sort of forgotten works by otherwise famous writers. Additionally, while some might think it unsporting to compare an unfinished manuscript and a published novel, I feel as though my relative antipathy to both Hurston and Wilder in my previous experiences of their work levels the field a bit. I categorize Their Eyes Were Watching God as a book that is just not meant for me as its target audience (ironic, given that Richard Wright accused Hurston of playing to white prejudices by writing in Black dialect in the book), and I don’t particularly like The Bridge of San Luis Rey or Our Town. But I’m happy to note that I had a much more engaging time with Herod and Ides, so let’s explore that.

[With Hurston, it’s a minor miracle we even have the Herod draft manuscripts—they were going to simply be thrown out and burned by the people sent to clear out her house, but were preserved by friend Patrick DuVal, who just happened to arrive in time to save Hurston’s papers.]

As the daughter of a Baptist minister and as a scholar, Hurston was writing Herod in part as a conversation with both the biased religious and secular sources surrounding Judea’s infamous monarch. Our largest near-contemporary sources on Herod come from biblical New Testament and from the works of Flavius Josephus (c. 37-100 CE), each of which have a vested interest in vilifying him. Christianity’s gospels are largely concerned with depicting Herod as the wicked false king of the Jews whom Jesus Christ was meant to defeat in a spiritual and temporal sense, and Josephus’ family were political partisans of the royal Hasmonean dynasty whom Herod’s dynasty supplanted. Meaning both have reasons to paint the king as a monstrous tyrant. Hurston, conversely, wanted primarily to put Herod in the context of his times using other sources—like contemporary Roman ones—to show, she believed, that Herod was not only not an evil tyrant, but one of the most successful rulers of his era.

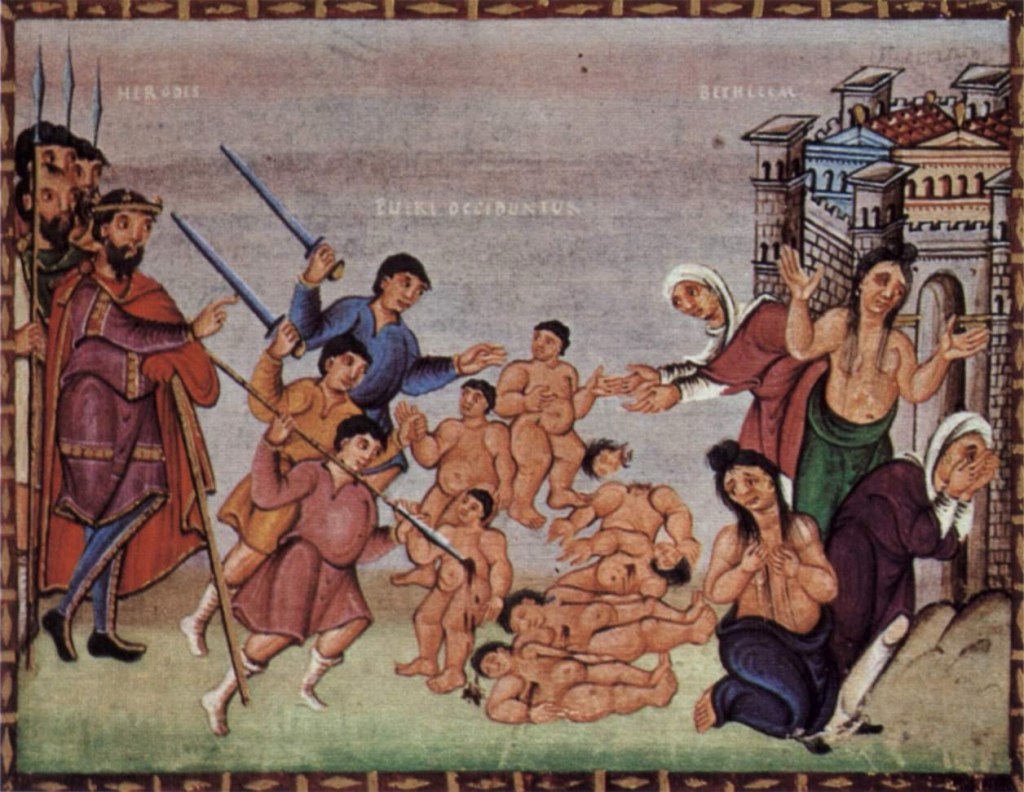

A lot of popular Herod mythology comes from the very nature of what the first century considered acceptable for “historical accounts.” Anything approaching what we consider factual history was simply not the aim of ancients writers. Josephus, and the author of the gospel of Matthew (whoever that actually was), for example, were writing in a literary tradition, more than a strictly historical one. I picked Matthew specifically because his gospel is the one that contains the major strike against Herod from the religious camp: the so-called Massacre of the Innocents. According to the biblical account (Matthew 2:16-18), Herod learns of the birth of Jesus from the astrologer-kings who come from the east to honor the baby, but who stop to pay their respects to Herod as curtesy dictates. Herod tells the wise men to find Jesus and then report back to him; ostensibly so Herod can honor him too, but secretly so the king can have this little rival killed before he becomes a problem. When the wise men are warned in a dream not to give this information up to Herod, he instead orders all of the male children in the Bethlehem area under the age of two murdered—a fate Jesus Himself avoids because angels also warn his human dad Joseph in a dream to go to Egypt before this happens, where the Holy Family will chill for a couple of years until Herod dies.

[The Massacre of the Innocents from a 10th century manuscript]

The issue is, like many things depicted in the gospels (or the Bible as a whole), there is just no other historical evidence that this massacre actually occurred. The other three canonical gospels don’t mention it, and neither do any secular sources. As I’ve intimated, Josephus was empathetically not interested in carrying water for Herod, and he doesn’t refer to it, either. Some scholars speculate that the massacre was a literary stand-in for Herod’s execution of his own sons—a thing that did happen—turned into a crime against the Son of God. And while obviously executing (many) members of your own family isn’t, like, something to be proud of, you, my readers, know that this kind of thing was just de rigueur for your typical first century Hellenistic monarch. And that is more of what Hurston is trying to get at with her novel: that some of Herod’s actions might seem brutal to us, but they were perfectly in line with the way political power was exercised in his era.

Another good example of ancient historical trope writing is how sources like Josephus write about Herod’s death. Josephus gleefully deploys the classic narrative for a tyrant who (regrettably) dies snug in their bed, by depicting Herod literally rotting away from from some terrible flesh eating disease that would for posterity be referred to as Herod’s Evil. In periods where a ruler’s physical body was mystically linked to the metaphorical body politic through divine kingship, having a supposedly bad ruler’s body rot away was a potent literary device meant to illustrate their effect on the “health” of their land and people. Suetonius does exactly the same thing when he wants to dirty up Tiberius, by claiming that as the emperor’s rule descended into tyranny, his body became gross and sore-ridden. This tradition would continue deep into the future, where many European monarchs would be branded with this kind of ignoble death. Aside from anything else, you have to remember that ancient disease identification was imprecise and none of these men had medical training, leaving these accounts suspect.

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΗΡΩΔΟΥ (Herod the King)]

Anyway, as interesting of a premise as I find Hurston’s idea to write a more wholistic Herod, if she had asked me for notes on this manuscript, my number one concern would be that in her zeal to defend Herod from the charged sources against him, I think she swings way too far the other way. Hurston’s Herod is basically perfect: he’s tall, dark, and handsome; he is a military genius, but also a serious scholar; the establishment hates him, but the peasants think he walks on water (ha); he is always in the right and essentially never makes any mistakes, except for being too nice and trusting. He’s basically the guy who says at the job interview that his only weakness is that he cares too much. Every myth and argument against him is painted as weak, jealous people out to get him, including every wife, brother, and son he kills to stay in power.

As I said in my Goodreads review, making Herod this good does the something worse than making him a baby-killing monster—it makes him boring. Because although, like me, Hurston is committed to writing fiction based on real historical sources, at the end of the day, we’re still writing fiction and fiction should be entertaining. At first, Hurston’s superlative approach to Herod made me think that she was setting up a sort of tragic Oedipal-style reversal for him (a “he had it all before the fates intervened” kind of thing). But nothing in her (admittedly incomplete ending notes) suggests this. Although disjointed because it’s unfinished, I expected this in the episode where Herod orders the death of his beloved queen, Mariamne I, something that has been a staple of tragic art for centuries. Accused of plotting against him, Herod has her executed along with what remained of her Hasmonean family, and most sources treat Mariamne as another innocent murdered by her husband. Although portrayed as a stupid dupe to her mother, Hurston has Mariamne as truly guilty and therefore her Herod is completely justified in killing her. I would have accepted this if it had acted as a character turning point for Herod, like he becomes less trusting and maybe makes some bad decisions based on this betrayal. But nope, he’s still just jaunting along, hot and righteous, and anyone who opposes him is defeated with minimal inconvenience. Honestly, Superman takes longer to deal with adversity than Hurston’s Herod.

[Speaking of too-cool-for-school Superman protagonists…]

I kid, I kid. Thornton Wilder’s Julius Caesar in The Ides of March has more nuance than that. Wilder takes a similar approach to Julius as a character as I do, where he cool, smart, and generally ahead of the curve on things, but not to point where he is infallible. It’s a small distinction to Hurston’s Herod, but an important one. Wilder deploys a stylistic choice in Ides that I think helps with this, which is choosing to make the book an epistolary novel, so you not only have Julius’ perspective on himself, but also the perspective of around half a dozen other characters, both friends and foes. I know epistolary novels are divisive among readers, but I for one am never sorry to see them turn up. Having the characters converse with each other by letter brings an intimacy to their interactions, which I think is always a bonus when you’re trying to help your readers connect with characters from a distant time period. Compare this intimacy with Hurston’s decision to have her characters and narration mimic the semi-heroic cadence of her first century source materials; hers might be closer to being “authentic,” but coupled with her paragon protagonist, it creates a rather emotionally distant reading experience.

Despite its title, the main focus of Ides is actually on the disastrous Bona Dea festival that led to Julius’ divorce from his second wife, Pompeia. Unlike Hurston setting out to correct what she saw as a biased historical interpretation, Wilder is consciously fictionalizing his ancient records. He follows the general tenor of his sources, but he purposely moves the Bona Dea incident up in the timeline from 62 BCE to just before Caesar’s death in 44 BCE. He also resurrects many characters who would be alive for the early event but not the later, like Cato and Catullus, as well as Caesar’s Aunt Julia, who was historically dead for both. This drove some more academic critics crazy, but Wilder was upfront in his note at the beginning that the novel is a “fantasia,” rather than hard historical fiction. This sense of unreality is heightened by the fact that sometimes the letter timeline shifts back and forth in a nonlinear fashion, so characters’ perceptions are in constant flux. Again, this is an irritant to some readers, but I think these are the kinds of interesting choices you can make as a writer when working in such well-trodden ground. We can go back and forth in time because it ultimately doesn’t matter—we know the Ides are coming and everything leading up to it will ultimately be swept away by its fallout.

Considering their shared historical orbit, it’s perhaps surprising that Herod and Ides share only one active character, and that’s Cleopatra. Neither Hurston nor Wilder are invested in breaking particularly new characterization ground with the queen of Egypt—Hurston in particular leans heavily on the anti-Cleopatra Roman sources—but it’s still interesting to chart the differences. Hurston’s Cleopatra is the classic model: beautiful, conniving, and utterly ruthless. Hurston needs to keep her Cleopatra evil in part to give more shine to her perfect Herod, who can of course can see through the seductive queen’s wiles and can heroically resist her charms. And while she does want to use him like she does everyone, naturally, her Cleopatra is desperate to jump Herod’s hot, manly bones. Meanwhile, Wilder goes with the more mercurial Cleopatra, childishly charming one minute, cool and calculating the next. His version of the queen is more enticing as a character, but I do think suffers from some good ol’ fashioned misogyny on Wilder’s part as many of the historical Cleopatra’s accomplishments (like learning Egyptian) are framed as things Julius suggested to her. I suppose Wilder could respond to my charge by saying we only hear those kinds of assertions from Caesar himself and he is an unreliable narrator, which is a fair cop. My response to that is Caesar is never refuted in this matter in the text, so misogyny is left to stand. But as someone who has Cleopatra as a series antagonist, too, I guess I should be careful where I’m flinging my stones in this glass house.

Another point Wilder could use to fend off my argument is that while he is perhaps occasionally unfair to Cleopatra, he gives a surprisingly nuanced depiction to the much-maligned Clodia Pulcher, who is usually drawn as little but a frivolous whore in most ancient accounts. Wilder allows Clodia’s actions to be driven by traumas that leave her nihilistic about life generally and men in particular in an extremely human way that is eminently relatable. Driven by Wilder’s interest in the writings of Jean-Paul Sartre at the time, Julius and Clodia are his great philosophers in the novel, and just because he ultimately rejects Clodia’s (Sartre’s) atheistic existentialism, Wilder is sympathetic to the thought process.

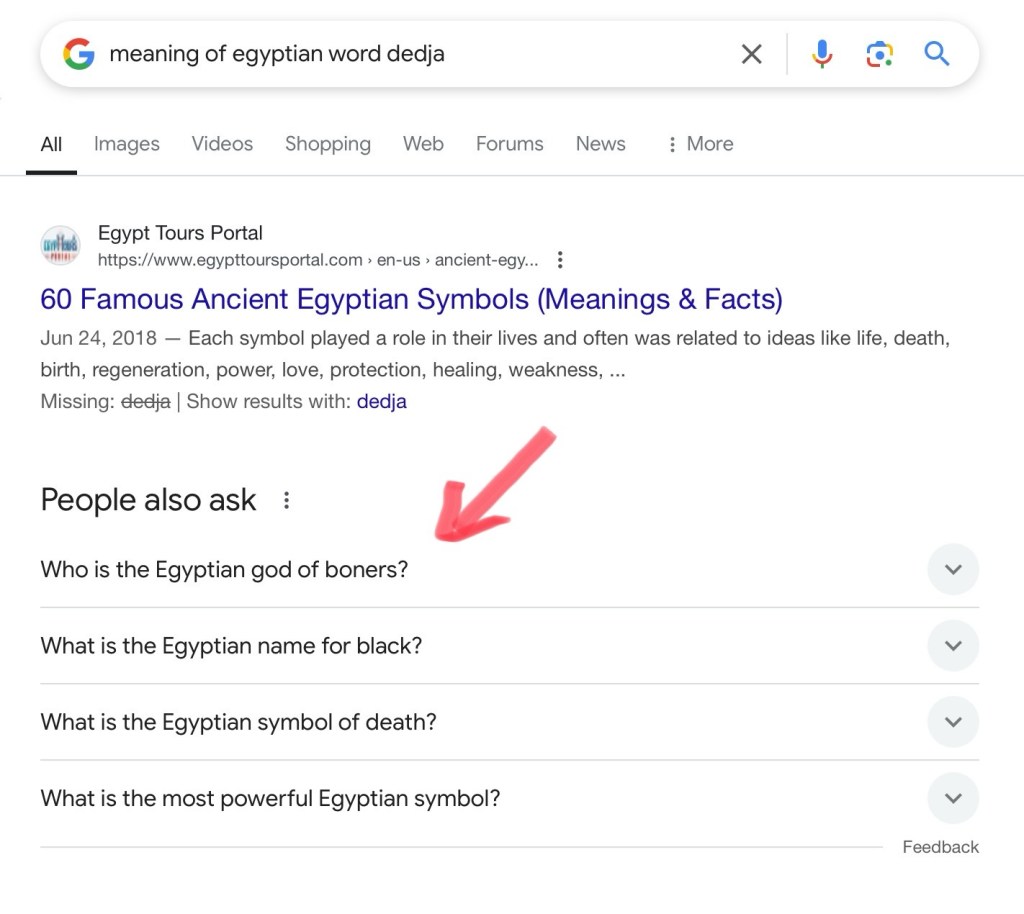

In closing, I would really recommend both of these books to any of you who are interested in this period of ancient history. While incompletely edited together from multiple draft manuscripts makes Herod a necessarily flawed work, Hurston is attempting such a unique perspective of a well-worn historical villain, using such a deliberately unique narrative style, that I still think it is worth the read for the nuts and bolts of craft, if nothing else. And Ides is just a classic midcentury novel that I think has been unfairly buried in the catalog of its well-respected author in favor of his more “Americana” works. …And maybe if somebody else reads Ides, they can tell me what Egyptian word Wilder was going for with Caesar and Cleopatra’s mutual endearment Deedja. I have been puzzling over this for weeks, and I still have no idea. Maybe a baby-talk version of djed (as in “my strength”)? I don’t know—leave you best guesses in a comment.

[After scouring my dictionaries, I broke down and asked Google, but everyone there had more important questions to ask… (Yes, it’s Min)]

Leave a reply to sarahlholz Cancel reply