“O God, whosoever thou art that didst ordain this flight, show mercy and bring me to the Residence! Peradventure thou wilt grant me to see the place where my heart dwelleth. What matter is greater than that my corpse should be buried in the land wherein I was born?” – The Tale of Sinuhe (Gardiner translation)

“My name was once inscribed in Pharaoh’s golden book, and I dwelt at his right hand. My words outweighed those of the mighty in the land of Kem; nobles sent me gifts, and chains of gold were hung about my neck. I possessed all that a man can desire, but like a man I desired more—therefore, I am what I am. I was driven from Thebes in the sixth year of the reign of Pharaoh Horemheb, to be beaten to death like a cur if I returned…” – The Egyptian

The people in my life always know that they can come to me with their obscure ancient literature bits, which is probably why one of my friends from law school knew I was his audience for a joke about how Fox News was not only disrespectful to call Vice President Harris “the original hawk-tuah girl” (it’s a fellatio meme that I don’t really don’t want to go into more detail on), but incorrect. Because everybody knows that the original hawk-tuah girl is obviously Shamhat, the sacred prostitute who tames the wild man Enkidu in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

But it was fortuitous to be gifted a Gilgamesh joke when I was already planning to talk this week about perhaps the only other ancient story that can reasonably challenge it for the title of oldest surviving piece of written literature: The Tale (Story) of Sinuhe. Written in Egypt during (we believe) the 19th century BCE, Sinuhe is an archetypal story of loss, renewal, and the yearning for a homeland that would set the tropes for non-mythological literature not only in Egypt, but throughout the ancient Middle East.

The relatively simple story itself can be summed up as follows: Sinuhe, a royal banner man to the pharaoh, is thrown into fear and despair at the death of the king, which causes him to flee Egypt. He eventually arrives in the land of Retjenu (Middle Egyptian: Rțnw), broadly the Canaanite parts of greater Syria, where he is befriended by their king because of his superior abilities and eventually marries a princess. This leads to some jealousy among the native nobles, and Sinuhe must defeat a challenger to his newfound power before his position is entirely secure. He lives for many years in prosperity in Retjenu, but as he ages, his soul’s longing to be reunited with Egypt grows stronger. The new pharaoh invites Sinuhe to return, and Sinuhe rejoins the royal court and his Egyptian identity, summed up by his wish to be buried in his homeland according to the customs of Egypt. The tale is a part of this purpose, serving as a funerary/coffin text both for the character of Sinuhe and for other Egyptians who included it among other burial compilations like the Pyramid Texts and the Book of Coming Forth By Day.

The oldest copies we have of Sinuhe date from around the 1800s BCE, during the reign of 12th dynasty pharaoh Amenemhat III, but the story itself concerns dynastic events from about a century prior during the reign of Amenemhat’s dynastic founder and namesake, Amenemhat I. He is the pharaoh whose death sets the plot in motion, and his rise and reign are worth examining a little closer to flesh out the context of Sinuhe. And I say his “rise” because his reign was not a historical given, as like many Egyptian dynastic founders, Amenemhat was not of royal blood.

We believe Amenemhat served as the grand vizier of the previous pharaoh, Mentuhotep IV (?1991-7 BCE), the last pharaoh of the 11th dynasty. Not much is known about Mentuhotep or his reign, but based on Amenemhat’s involvement in several military operations before and around the time he took the throne, there appears to have been a somewhat unstable political situation in Egypt. The evidence that Amenemhat the pharaoh and Amenemhat the vizier are the same person comes from inscriptions along Wadi Hammamat, the ancient quarry and trade route that connected inland Koptos near Thebes to the Egyptian port of Quseir on the Red Sea. These are most of what we know about Mentuhotep and the name of his vizier, both of which are connected to descriptions of two prophetic events: the birth of a gazelle on the stone that would be made into Mentuhotep’s sarcophagus lid, and a violent rainstorm that revealed an overflowing well. Egyptologists hypothesize that these two events, both symbols of renewal and abundance, were recorded by Amenemhat to show that both Mentuhotep and the gods approved of his ascension to the throne following his lord’s death.

And he may have needed the support of divine auguries, because it has been suggested that Amenemhat may have murdered Mentuhotep and usurped the throne, rather than simply inheriting it from a childless king. A violent change of ruler may also explain the rumblings of unrest recorded around the time of Amenemhat’s ascension, though it should be stressed that there is no direct evidence that this is how Amenemhat came to power. Viziers and other high-placed retainers being officially or unofficially adopted as the king’s heir was not unusual in Egypt—Tutankhamun’s vizier Ay comes to mind, though their are nagging unsubstantiated rumors of foul play there, too—so a peace transfer of title is still possible. Given the short duration of Mentuhotep’s reign, it could be that he was elderly and/or ill when he was crowned. Or perhaps even, like Tut, young.

The lack of records on how Mentuhotep was related to the previous several pharaohs before him itself suggests that a dynastic crisis was already underway long before Amenemhat may have intervened. Mentuhotep IV could have been a young son of Mentuhotep III, or possibly his half-brother. The idea of Mentuhotep IV being young rather than old to potentially explain his lack of biological heirs, in my opinion, is supported by his Wadi Hammamat inscriptions only mentioning one woman, Imi, who is identified as his mother, with no other women listed as queens or wives/sisters. Imi’s own lack of titles like “King’s Daughter/Sister/Wife” suggests to some Egyptologists that she was lower-ranked, non-royal concubine in Mentuhotep’s father’s harem (whereas royal queens were usually biologically related to the pharaoh in at least one way, and were designated as such). Mentuhotep IV being a relatively young, low-ranking prince with an obscure mother and a candidate of last resort for his dynasty might also explain his lack of pharaonic paper trail during his brief reign. And if the dynasty had been on its last legs before him, it might explain the general ease with which his equally non-royal vizier was able to supplant it.

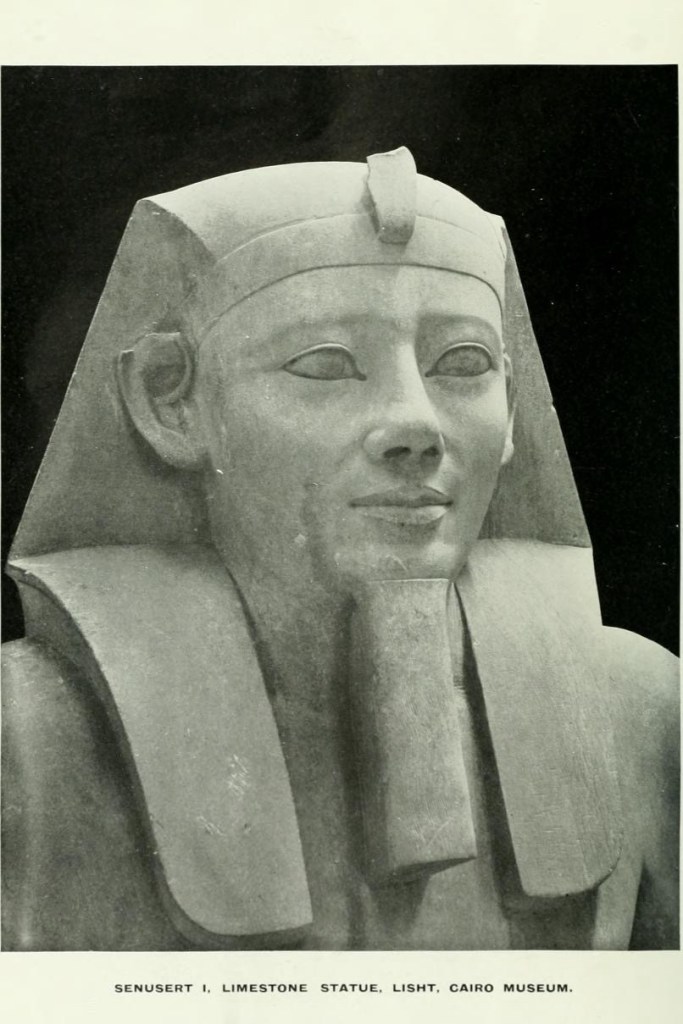

However he arrived at his position, Amenemhat I reigned for thirty years, long enough to well establish himself and his new dynasty. He is the first recorded pharaoh to have ruled at least part of this time with a co-ruler, his son and heir Senusret I. But I think it’s the equally murky circumstances around Amenemhat’s death that have led to the persistent speculation around how he got the throne from Mentuhotep. In the sebayt (instructing/teaching) poem the Instructions of Amenemhat, thought to have been commissioned as a memorial text for his father by Senusret, the ghost of Amenemhat alleges that his death was an assassination carried out while Senusret was fighting enemies in Libya:

“It was after supper, when night had fallen, and I had spent an hour of happiness. I was asleep upon my bed, having become weary, and my heart had begun to follow sleep. When weapons of my counsel were wielded, I had become like a snake of the necropolis. As I came to, I awoke to fighting, and found that it was an attack of the bodyguard. If I had quickly taken weapons in my hand, I would have made the wretches retreat with a charge! But there is none mighty in the night, none who can fight alone; no success will come without a helper. Look, my injury happened while I was without you, when the entourage had not yet heard that I would hand over to you when I had not yet sat with you, that I might make counsels for you; for I did not plan it, I did not foresee it, and my heart had not taken thought of the negligence of servants.”

This is comparatively much more direct than how Sinuhe recounts the king’s death, which is framed as very sudden, but with no allusion to foul play aside from the otherwise inexplicable fear Sinuhe greets the news with. This has led to some suggesting that Sinuhe was an accomplice of the assassins, or had knowledge of their plans, and that is the reason he suddenly abandons Egypt in the dead of night. However, according to the Instructions, Amenemhat claims that he was killed by members of his bodyguard, and that is not how Sinuhe describes himself. In the opening lines of his story, he tells us that he was “a henchman who followed his lord, a servant of the Royal harim attending on the hereditary princess, the highly-praised Royal Consort of Sesostris [Senusret].” This implies that Sinuhe served in the household of Senusret’s queen and sister-wife, Neferu, who was also a child of Amenemhat, rather than the king himself. This doesn’t negate the possibility that he was aware of a plot, but it seems to make his active participation less likely.

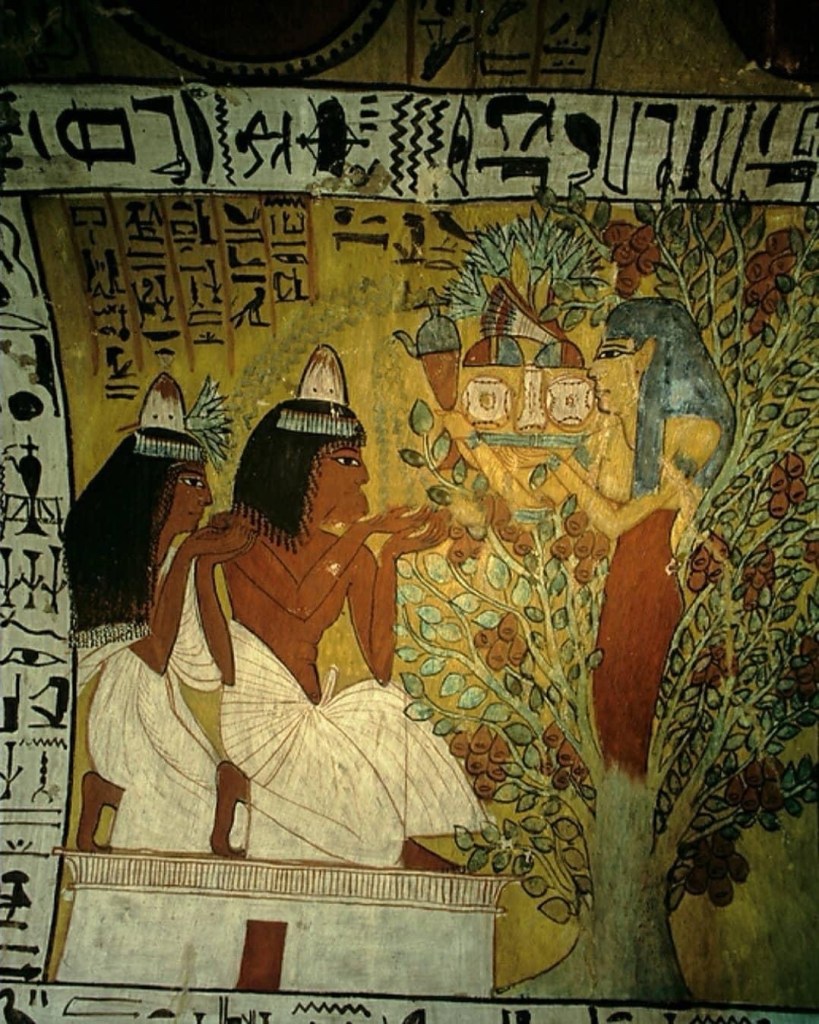

In my view, even if he was not guilty of an actual crime, Sinuhe’s extreme reaction to Amenemhat’s death can be parsed in one of two ways. One is entirely symbolic, as many things are in ancient Egyptian literature: that the disorder caused by the violent death of a god-pharaoh leads to a complete upending of order (ma’at) in Egypt that leads to the people feeling as though the very ground has been ripped out from underneath them, symbolized by Sinuhe’s flight from Egypt. He can only “return” when the new god-pharaoh, Senusret, has restored ma’at in the land and called Sinuhe “home.” Even more esoterically, Sinuhe’s (whose name, sA-nht, means “son of the sycamore”) journey may be a sublimation of the death and rebirth cycles of the funerary texts in a slightly different package. The pharaoh’s death is a reenactment of the Osiris myth, where the death of a god leads to renewal in his god-son, and by extension, opens that death and rebirth to the Egyptian people. Sinuhe must “leave” Egypt by “dying” (going to a strange and unknown land), where he experiences trials that test his courage and integrity (the various tests the soul undergoes in the Duat). He is rewarded for his triumphs, then he is recalled to Egypt by the intervention of the new pharaoh-god and reborn as an Egyptian once more—a literal rendering of the prayers of the Book of the Dead that ask for the soul to be able to issue forth and return at will. Sycamore trees are sacred especially to Hathor, who is more well known as the goddess of love and fertility, but just as the king of the dead, Osiris, has connections to fertility through the agricultural cycle, Hathor also has chthonic properties. In this function, she was the Queen of the West, i.e., the Duat, which may have derived from either her sometimes-syncretism with Osiris’ wife, Isis, or her more ancient link with the deathly war goddess Sekhmet, of whom she was often portrayed as the other side of. Either way, many Egyptologists see Sinuhe’s name as a connection to these underworld mythologies.

If we wish to see the Sinuhe story as less allegorical, the protagonist’s flight may be one of personal guilt, rather than literal. As a, based on his later marital history, fertile man permitted to serve in the household of the crown princess, Sinuhe would have occupied a place of extreme trust within the royal family. Even if he didn’t know about the assassination plan, he might have felt, as such a trusted retainer, that he ought to known about it. In this scenario, Sinuhe is more like the cop who turns in his badge after he fails to stop a crime, and his self-imposed exile is like him retiring to a cabin in the woods until he’s called back. We have to remember that Amenemhat would have been held as a god by his subjects, and injury to him would have been held as impiety against a deity. If we slip back into symbolism again, injury to a god requires penance, which Sinuhe’s exile could serve as—to be separated from both the good of Egypt itself and the sheltering good of the gods’ (pharaohs’) favor. In this light, Sinuhe’s prosperity both in exile and in his return is a reward for his extreme piety toward the divine persons of the royal family. His text describes the elaborate tomb and grave gifts that Senusret bestows on him, proclaiming, “[t]here is no poor man for whom the like hath been done”, emphasizing the status his seemingly nonsensical actions have earned him.

The literary legacy of Sinuhe has been immense, from its own through to ours. It is likely that it influenced (and was influenced by) the contemporaneous Instructions of Amenemhat, but its inclusion among popular funerary texts well into the New Kingdom a millennium later, shows its staying power. It became the template for much of ancient Egyptian folklore, to the point that any story where the hero goes on a journey to a faraway land inevitably references Sinuhe. Some literary and biblical scholars point to Sinuhe as a source for some of the elements of the patriarch Joseph’s story, which by best current estimates took place some three hundred years later between the end of the 12th dynasty and Egypt’s Second Intermediary Period (~1600-1500 BCE). The parallels between Sinuhe, an Egyptian who finds success in exile in Canaan-Syria, and Joseph, a Jewish-Canaanite who finds success in exile in Egypt, are considerable. And just as Joseph’s story (especially the Potiphar’s Wife motif) would diffuse widely through Mediterranean and European folklore, Sinuhe was ubiquitous enough by the time that the Torah was being composed it might have influenced parts of the narrative, particularly given both stories’ focus on righteous suffering and redemption.

Closer to our own time, Sinuhe and his milieu continue to provide inspiration. The Nobel-winning Egyptian author Naguib Mahfouz, who often drew on the ancient history and literature of his country, wrote a short story in 1941 based on Sinuhe and the Instructions of Amenemhat called “The Return of Sinuhe” (Egyptian: “Awdat Sinuhi”), where Mahfouz adds a spicy love triangle between Senusret and Sinuhe to explain the latter’s strange flight after the death of Amenemhat. A few years later in 1945, Finnish novelist Mika Waltari used the Sinuhe story as a jumping off point for his historical fiction novel, The Egyptian (Finnish: Sinuhe egyptiläinen). In The Egyptian, Waltari’s protagonist is a man named Sinuhe living not as a royal guardsman in the chaos of the nascent 12th dynasty in the Middle Kingdom, but as a doctor caught up in Akhenaten’s religious revolution in 18th dynasty of the New Kingdom. Waltari uses the bones of the original Sinuhe tale to draw parallels as his Sinuhe’s (mis)adventures take him across the ancient Middle East and back to Egypt, while the rise of Akhenaten’s new world order and the concurrent rise of Sinuhe’s friend Horemheb hover in the background. But as it was written during the war years in Europe, The Egyptian is pessimistic about the nature of power and those who wield it, and Waltari’s Sinuhe ends not in the bosom of his beloved Egypt, but as still an exile.

In the newest millennium, Booker-winning Nigerian author Ben Okri wrote a play three years ago called Changing Destiny, which explores the Sinuhe story through the lens of post-pandemic alienation, immigration, and identity. The play sticks fairly closely to the plot of Sinuhe, while adding thoroughly Egyptian embellishments like the character of Sinuhe being represented by two actors, one of whom is the person Sinuhe and the other who is the embodiment of Sinuhe’s ba, his soul. This both illustrates the internal conflict within Sinuhe about his guilt and where he belongs, but also very neatly references one of the other famous Egyptian coffin narrative texts, a poem usually called in English “A Man’s Dialogue With His Soul,” where the protagonist has a long discussion on morality and right action with his ka. When describing the core theme of the play, Okri says, “All is real, all is dream. A person who fled for reasons they did not know, arrives somewhere they did not expect, where the synthesis which is at the core of a great civilization is at the root of a new genesis.” (Introduction, vii). And I think that is the core of the Sinuhe story as a whole and why it continues to resonate four thousand years later. Life itself is a journey undertaken as a flight into the unknown all the while we yearn for a sense of belonging we can but dimly remember. All has happened, all is ma’at.

Leave a comment