As promised, this week we’re back with Pliny the Elder and his Natural History, and we’re here to tackle Books 12-27, the dreaded plant books. Since we’ve already introduced Pliny and his general deal, we’ll pretty much delve straight in, but if you missed the first part, you can find it here. As with the first eleven books we covered last time and my title implies, to avoid a full recap of what is essentially an encyclopedia, this is going to be a breezy stroll through what stood out or amused me as I ground through four of ten Loeb volumes’ worth of material. We have so many plant sections to get through, so let’s get started!

Book 12 starts with a tangent about how Pliny thinks earrings are dumb (XII, i.2), but he settles into his plant material relatively quickly, with a brief overview and some trees. A lot of Pliny’s tree information comes from Juba of Mauretania, though as usual, especially when pertaining to trees native to Africa and the Middle East. He describes how trees of “exceptional height” were once dedicated to the gods: “…nor do we pay greater worship to images shining with gold and ivory than to the forests and to the very silences that they contain.” (XII, ii.3) We learn that an “expensive” ancient linen was produced from cottonwood down (XII, xxii.40), that employees in the Alexandrian frankincense factories had to strip down before they left work as an anti-theft measure (XII, xxxii.59), and that most of Rome’s cinnamon was harvested in Ethiopia with a ritualized process sacred to Jupiter and his (presumably) local syncretic equivalent, Assabinus (XII, xlii.89), though Pliny has no additional details about what was done. He also has a good laugh that the expense of the Gallic tribes, claiming that once they got a taste of wine and olive oil, they’ll keep going to war with Rome to maintain their supply (XII, ii.6), while chastising his fellow Romans for spending all their money on costly, imported pepper and ginger (XII, xv.29). Eat our (crappy) local pepper, you effetes!

Book 13 is mostly about the plant products of Egypt, particularly in regard to perfumes and papyrus. He tells us that the best Egyptian perfumes from Mendes, city of the Khnum-adjacent ram god Banebdjedet (XIII, ii.4), and while the Romans enjoyed a panoply of scents, Pliny believes rose to be the most popular/widely used (XIII, ii.9). Although, as an old-school Roman man, he has little patience for other men who overindulge in perfumes—citing famous aesthete Lucius Plotius, who was proscribed by the Second Triumvirate (Octavius/Antony/Lepidus), but who supposedly caught in his hiding place because his perfume gave him away. He even goes so far as to say that Plotius’ addiction to such luxuries basically excuses the Triumvirate for their otherwise harsh sentence on him—apparently smelling too good is a capital offense for Pliny. On the papyri front, he claims that papyrus wasn’t used before Alexander’s conquest of Egypt (XIII, xxi.69), but it is unclear from the syntax if he means that Rome didn’t use papyrus before then (believable) or if no one did (wrong and insane). Like with many Roman products by Pliny’s time, the best quality papyrus was called “Augustus” in the empire, and the second-best, “Livia” (XIII, xxiii.74), to honor the two highest-ranking gods in the imperial cult, the Divus Augustus and the Diva Augusta. Also, this is the book where we learn that ancient Romans were aware that plants have genders (XIII, vii.31).

Book 14 is about wine and beer, important information for people who sometimes had limited access to potable water. As would be expected for a respectable Italian, Pliny doesn’t have a deep familiarity with the latter, calling beer “grain soaked in water” (appetizing!—though accurate) (XIV, xxix.149), but in keeping with what I just said about Augustus and Liv, he makes sure to record their favorite wine varietals (Setinum and Pizzino, respectively) (XIV, viii.60-1). He also says that famous wino Tiberius enjoyed having his wine aerated with smoke, especially with woods from Africa (XIV, iii.16), and that Lucius Calpurnius Piso Pontifex got the praefectus urbi job from his imperial friend because Lucius was able to keep up with Tiberius on a 48-hour drinking binge (XIV, xxviii.144-5). Salute!

Book 15 covers fruit, including a (obvious) deluge of information about technical-fruit olives and their oil, the aqua vita of Roman life. Once Pliny finally stops talking about olives, though, we do get into some other fruits that Romans had access to. Much like today, peaches’ limited shelf life made them the most expensive fruit in the ancient world—Pliny quotes a price of as much as 30 sesterces each (XV, xi.40). Which is a shame because cherries didn’t arrive in the city until after the Mithridatian wars in 74 BCE (XV, xxx.102) and apparently Roman strawberries suck (XV, xxviii.99). The major fruit of the Mediterranean, as today, was figs, and Pliny knows about fig wasps and their symbiotic relationship with the plant, but calls them “gnats” (XV, xxi.79-80).

Book 16 comes back to trees and more specifically arboriculture, and Pliny kicks things off with a very 19th century imperialist statement that the miserable “backwards” tribes of deeper Germany and the Dalmatian coast should be glad that Roman civilization has colonized them and elevated their wretched lives with agriculture (XVI, i.1-4). Once he gets that off his chest, we get into the trees and shrubs, like how the oak leaf Civic Wreath became a later symbol of the clementia Caesaris attributed to the Divus Julius (XVI, iii.7), and how Romans sometimes used hollowed out pine and alder logs for water pipes (XVI, lxxxi.224). Pliny mentions that original cult image of Artemis in her temple at Ephesus might have been made of ebony wood (XVI, lxxix.213), the memory of which is what the marble Farnese Artemis from the 2nd century CE above may be recalling. He also drops a fascinating fashion history detail, mentioning that Roman women soled their winter shoes with cork (XVI, xiii.34).

Book 17 is more arboriculture, and also where the cold, dark reality of your reading life begins to seep in. That you are six books into the plant section of the Natural History and you have ten more of these suckers to go… Here we just have basically a laundry list of agricultural advice mined by Pliny almost entirely from literary sources: a ton of Virgil (XVII, ii.19-iii.29), but also Cato, Homer, and even Cicero (XVII, iii.29-38). Personally, I don’t know if I’d go a shut-in (Virgil) and a fancy boy (Cicero) for practical farming advice, but the Georgics was used as such through the medieval period, so make of that what you will. Cato is less suspect, as he was dead serious about farm management, and I don’t know—maybe the ancient hive mind that was “Homer” came up with some viable ideas. If climate change causes a future societal collapse, I guess I’ll find out as I try to use my copy of this text to make my backyard grow any of this stuff. To wrap up this book, in something that feels straight out of Cato, Pliny believes that tree medicine is analogous to human medicine (XVII, xliii.252), and recommends “bloodletting”(sap-letting) your trees for their health (XVII, xxxix.246).

Book 18 is about cereals, as in grasses with edible grains. This also the first time poisonous plants are mentioned, though Pliny doesn’t blame nature for producing them, only mankind for using them (XVIII, i.1-4). He mentions potential plant-based etymologies for the Roman cognomens Piso (“pounding corn”) and Lentulus (lentils) (XVIII, iii.10), while claiming that there was totally a line in the lost Sophocles play Triptolemus that said that Italian corn was the best (XVIII, xi.65). Oh, and just a reminder that when ancient people say “corn,” they mean wheat/barley/oats—none of these people or their descendants are going to clap eyes on an ear of maize until 1492 CE. The most interesting tidbit to me in this section, however, is that Pliny might be able to provide additional corroboration of the bean part of the Lemuria ceremonies that otherwise we only know of from Ovid’s di Fasti—“…or, as others have reported, because the souls of the dead are contained in a bean, and at all events it is for this reason that beans are employed in memorial sacrifices to dead relatives.” (XVIII, xxx.118-9). Pliny also claims to know of a certain plant that if buried at the four corners of a field will protect crops from starlings and sparrows, but also doesn’t know the name of it (XVIII, xlv.159-60). Which I’m sure will be of great comfort to modern farmers, as house sparrows and starlings cause upwards of a billion dollars of agricultural damage annually in the US alone…🤦♀️

Book 19 concerns itself with more common plant-based fabric sources than the previously mentioned cottonwood linen, especially flax, one of the most used plant fibers in the ancient world. Pliny claims that flax sails are so efficient that with the correct wind, Galeriys did Alexandria to Messina in seven days, and the astrologer Balbillus once did the trip in six (XIX, i.3), both incredible feats in an era where travel tended to be measured in weeks or months rather than days. He and the Romans were also under the impression that asbestos was a type of flax, rather than a mineral, which is why it is here in the plant books rather than the (much) later rocks and gems sections. Unfortunately, like the medieval kings referenced above, they were also using it to produce extremely expensive cloths that rich people were dropping pearl-equivalent (another infamously expensive item) money on (XIX, iv.20-1). When we get to medicines, my first recommendation for respiratory illnesses is to take off your asbestos toga. Or you could try some rue, though Pliny warns that stolen rue grows better (XIX, xxxvii.123). But as a more relatable anecdote, know that Romans were also concerned about garlic breath (XIX, xxxiv.111-4).

The rue bit from the last book must have got stuck in Pliny’s mind, because Book 20 comes back to it while introducing the first round of medicinal plants. He calls rue “among our chief medical plants” (XX, li.131), but most of the stuff in here follows Cato’s advice, so know that if you’re not using rue, you’re slapping cabbage on everything—including your genitals (XX, xxxiv.89). I mean, it’s harder to worry about your garlic breath when the first thing that your date is going to see when they take off your clothes is your coleslaw topical…

In what feels like the first casualty of Vesuvius preventing Pliny from going back and editing most of the Natural History, he gets sidetracked from cataloging medicinal plants for the whole of Book 21 to circle back to garden plants. A surprising amount of space is devoted to plant/flower chaplets and their construction, including how Augustus’ daughter Julia would place flower crowns on statues in the cities during her infamous “night frolics” (XXI, vi.9), and how Cleopatra proved her love and loyalty to Antony by showing him that she could have kill him at a banquet if she had wanted to with the petals of her chaplet, which she had dipped in poison (XXI, ix.12-3). Most of the rest of this book is otherwise tied up with bees and honey. Romans had also made the connection between bees and thyme for the best honey (XXI, xxxi.56), but perhaps because it was so otherwise efficacious, Pliny devotes a lot of time to honey that is either poisonous or drives you insane (XXI, xliv.74-xlv.78).

Book 22 returns to medicinal plants, and aside from the weird topic blip of the last book, what becomes both increasingly obvious and interesting about the botanical books is the beginning of some serious textual lacunae in Pliny’s manuscript, and apparently a ton of discrepancies between him and his sources (such as the Greek pharmacologist Dioscorides, who he uses heavily in these sections). Pliny tended to write by notating what was read to him or vis versa, so these could be copying mistakes between him and his amanuenses, but in the end we don’t know. Apart from the mountains of plant information, much of the length of these Loeb volumes is tied up with frantic notes by the translators, trying to either mark lacunae or keep track of all the wrong or misquoted material. But some of what Pliny tells us can be trusted, like when he’s relating specifically Roman information, as when he explains that the grasses used to construct the civic crown granted to a person who preserved the army in a battle, the material used wasn’t a specific plant (like the aforementioned oak leaf crown), but rather a plant growing in the place where the crown was earned by the recipient (XXII, iv.8). Also, Pliny thinks that mushrooms are just too much trouble to bother with: “What great pleasure can there be in such a risky food?” (XXII, xlvii.96-7)

Book 23 is still medicinal plants, and I’m sure that it will come as a huge shock that Romans thought a ton of things could be fixed by wine, grapes, and their vines or leaves! Although Pliny seems to be aware that milk is good for bones (XXIII, xxii.37), this is mostly the vino hype train, though he deplores the contemporary state of viticulture, bemoaning the proliferation of adulterated wines (XXIII, xx.33-5). He particularly mentions a trick where new wine was seasoned with resin, presumably to artificially age its taste. This worked about as well as you might imagine, and the resulting concoction was appropriately named called crapula (“hangover”) (XXIII, xxiv.46), which is definitely how I’d picture you feeling the next morning. But when you’re relying on wine to fix everything, it’s not surprising that people like Marcus Agrippa were also suffering from gout later in life (XXIII, xxviii.58)

I don’t want to blow your mind, but Book 24 is still about medicinal plants, but here is where it feels like we get into some real, practical home remedies. Malignant skin condition? Slap some acorn powder and salted axle-grease on that shit! (XXIV, iii.7) (based on information in a later book, Roman axle grease was probably pig’s grease (XXVIII.xxxvii.136)). Chapped lips? Try pine pitch! (XXIV, xxiv.40) Losing your hair? Try putting oak sap and bear grease on your pate! (XXIV, vii.13) Fix dislocations with any plant that you pull up without the “touch of iron” near where dogs pee! (XXIV, cviii.cxi) Pliny also suggests ground plane tree seeds in wine against “the poison of the bat” (XXIV, xxix.44), for those of you encountering poisonous bats on the regular. If you’re struggling to escape said poisonous bats, or any other wild animal, he volunteers “Therionarca,” a Cappadocian plant that will knock them out, though if you change your mind, you’re going to need hyena urine to revive them (XXIV, cii.163). Though this book also reveals that Romans are under the mistaken impression that kermes, a species of insects used for millennia as a red dye source, were “scarlet berries” that grew on holm oak trees, and they thought that worms (the kermes larva) spontaneously popped out of them occasionally, rather than deducing that they were insects instead of plants (understandable when you recall that insect reproduction was generally viewed as spontaneous at this point in history) (XXIV, iv.8).

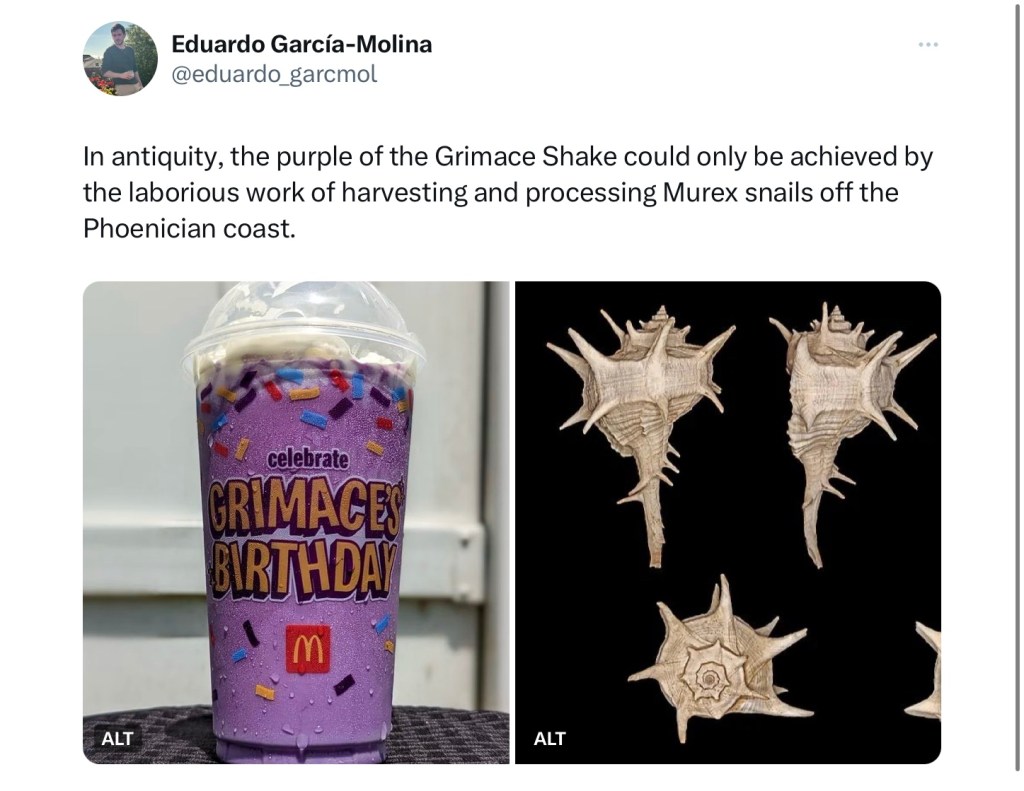

Pliny heard that you all might be getting tired of plants, but merely laughs like a supervillain and continues with more medicinal plants in Book 25. But he also reveals that he’s still mad about the Phoenicians refusing to spill about their murex recipe by going on a rant about people discarding ancient knowledge and hoarding any new knowledge they have from others (XXV, i.1-2). Still a Germanicus stan, Pliny mentions how he and his men supposedly found a spring that caused your teeth to fall out within two years and your knees to go (XXV, vi.20), on his way to finally agreeing to discuss poisons, which he admits can occasionally be used to beneficial effect, but flat out refuses to discuss aborficants or love potions (XXV, vii.25). Though using poisons as medicines makes more sense when one remembers that most of what any remedy was supposed to do in premodern medicine was to make you evacuate your entire digestive tract in one direction or the other, possibly both at the same time. “Why are they making you eat hellebore?? It’s poisonous!” you ask? Because they don’t expect it to be in you for very long… Speaking of hellebore, if you see an eagle while you’re gathering it, you’re gonna die within the next year (XXV, xxi.50). Also, don’t administer it on a cloudy day (XXV, xxiv.59). Gathering a plant called centauris triorchis is also dangerous, as a same-named hawk might attack you (CXV, xxxii.69). But a Scythian plant, scythice, supposedly worked like a real-world lembas bread, and if you kept it in your mouth, you would have “freedom from hunger and thirst” (XXV, xliii.82). Pliny also mentions that Spain had a custom of mixing a proto-health smoothie that was called “the hundred plant potion,” which was a hundred different plants mixed with honey wine—but of course he doesn’t know which plants were used and what their actual number was (XXV, xlii.85). So we’re doomed to only have stupid modern smoothies with maybe, six ingredients, tops.

Book 26 cares not for wails of your wives and children and marches on with medicinal plants. But we do also get Tithymallus (Romans call it “milky plant,” I think it’s the plant called euphorbia or spurge), whose white sap could be used as an invisible ink. Pliny describes writing love letters on the body of a lover with it, rather than risking paper or wax, and using dry sprinkle ash over the writing to reveal the text (XXVI, xxxix.62). But mostly Pliny spends a lot of time in this book bitching that most health problems stem from the stomach and its excesses (XXVI, xxviii.43), and being just as annoyed by coughs as we are (XXVI, xv.27-30). He says that leprosy originated in Egypt, and was unknown in Rome before Pompey’s time. He also claims that the cure for it used by the pharaohs was the Elizabeth Báthory Special, and they were supposedly bathed in tubs of warm human blood (XXVI, v.8). But if you have non-leprous abscesses, Pliny recommends fasting for the patient, and that “those with experience have assured us that it makes all the difference if, while the patient is fasting, the poultice is laid upon him by a maiden, herself fasting and naked, who must touch him with the back of her hand and say: ‘Apollo tells us that a plague cannot grow more fiery in a patient if a naked maiden quench the fire;’ and with her hand so reversed she must repeat the formula three times, and both must spit on the ground three times.” If you’re fresh out of naked chicks willing to do this for you, you can try mandrakes or figs (XXVI, lx.92-3).

Book 27 opens with praise for the Pax Romana, which allowed so many helpful plants to be discovered and spread throughout the Mediterranean (XXVII, i.1-3), so, yes, we’re still dealing with plants. But we do get to experience the Romans using aloe for literally everything except burns or skincare XXVII, v.14-20). While for us it’s a genus of snakes, Pliny describes a plant called natrix used to specifically chase away nightmare hallucinations (fatui) from women (XXVII, lxxxiii.107) According the translators’ notes, fatui usually translates as “clowns” (as in proto-jesters kept by some Romans), but it could also translate as “night-demons,” as it does here (n. b, p.455). Lady problems fill a lot of pages here, including onosma, which causes women to miscarry if they eat it, or even if they accidentally step over it (XXVII, lxxxvi.110). But after a semi-alphabetical list of medical plants that will nearly sap your remaining will to live, Pliny finally announces: “Such is all that I have been told or discovered worth recording about plants.” (XXVII, cxviii.143) Freedom!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Stayed tuned for the third installment and final nine books of Pliny’s magnum opus, and I promise that there will be nary a leaf to be found! (Unless the Romans mistake rocks or animals for plants again…🙄)

Leave a comment