I’m coming to my blog schedule late this week because we just got back from another short trip to New York City, and I’m still trying to get organized in the aftermath of that. Aside from some other activities, including scoring extremely good lottery tickets to Six, we burned another entire day at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where I managed to make it to whole wings of the museum I didn’t get to last time we were here. But the most exciting thing was we were able to see the recently opened Divine Egypt, an exhibition about the Egyptian gods—something relevant to me and many of you. Going in, I was a little apprehensive that this might be one of those scenarios where I’ve worked myself into a state of Knowing Too Much about what was on show to get as much out of it as a more “layperson” would.

[I was afraid it was going to be like that time when somebody asked me on Goodreads if The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Egypt included Thoth. Um, yes. A book that lists out the hour goddesses and fifty different snake deities also mentions Thoth…]

But, to my immense pleasure, I think that the Met has threaded the needle almost perfectly: Divine Egypt is designed to get the basics of Egyptian cosmology across to the uninitiated, but there is plenty for those of us who have fallen way too deep into the rabbit hole of the Egyptian pantheon that we’re no longer allowed to talk about it at most civilized parties.

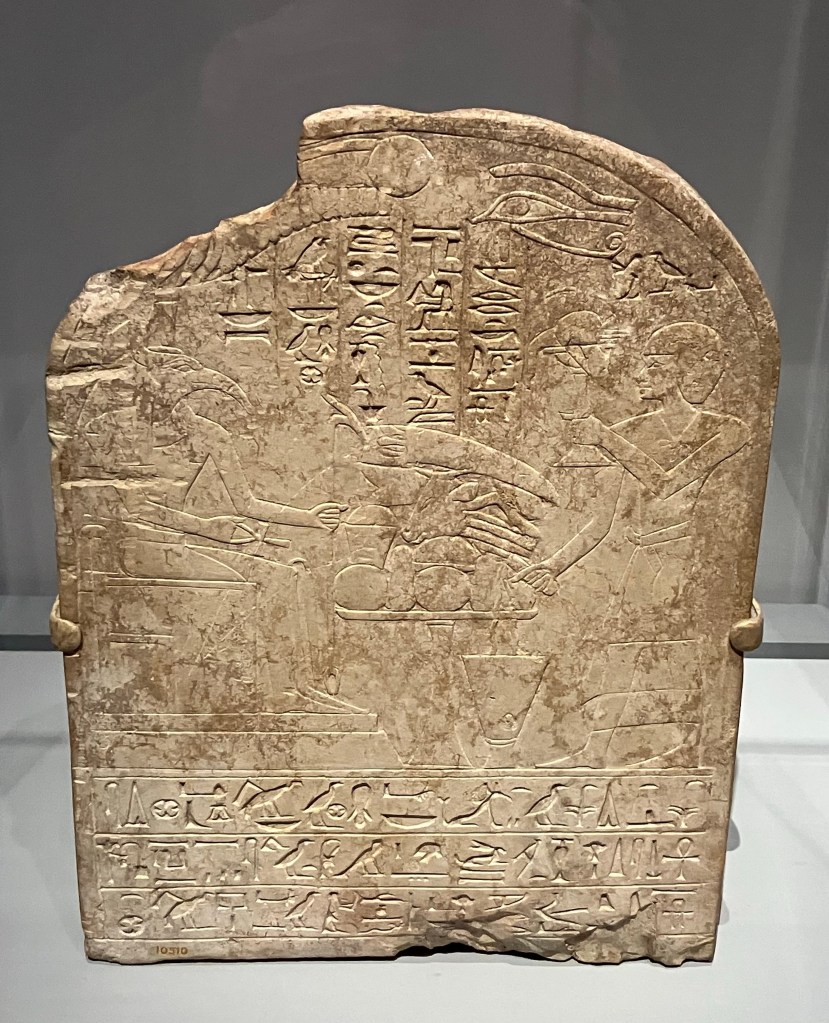

[Speaking of rabbits…they did do our girl Wenet dirty and merely called her “a hare goddess” in the description of this extremely famous stele of her, Hathor, and 4th dynasty pharaoh Menkaure🐇]

For every part where I could go, “Well, everyone knows that!”, there were artifacts that made me gasp and giggle with delight to see them. Both to see a number of well-known pieces in the flesh, but also a large array of unusual artifacts of gods famous and obscure. It would be impossible to cover everything, even in one of my patented photo bomb entries, but I want to give all of you a taste of what the Met has put together—either to share with those of you too far away to go yourselves, or to lure in those of you who are close enough to partake. Let’s look around!

First of all, I really liked the overall layout of the exhibition. Assuming you started from the right of the Amun statue in my header and ultimately exit through the gift shop, the exhibition begins with solar and solar-adjacent deities like Ra/Amun, Horus, and Hathor, and ends in the Duat with Osiris, Sokar, and Anubis—with everyone else filling in between. Building out the entire space to reflect the movement of Egyptian religious thought as it swings above and below the horizon is very fitting, and helps immerse you in what you’re seeing. This is also reflected, literally, in the exhibition lighting. Most of the hall is well lit with plain white walls, but for the chthonic gods, their space is kept in low light with black walls and (I wish I had thought to take a picture of this) a border of stars painted along the ceiling, to imitate tomb frescoes of the night sky (one of the positive afterlife domains of the Duat).

On the more technical side, as anything that wasn’t large and stone-made was, understandably, in temperature-controlled glass cases, I was very impressed that the lighting and glass quality choices made by the curator staff made it still very easy to get clear photos of the vast majority of these pieces without a ton of reflection and/or glare, which is a perpetual problem for me when I’m trying to document these kinds of exhibits. The only true exception to this was that reflections ratcheted back up in the underworld part of the hall because of the darker lighting, but as this was a larger, deliberate stylistic choice, I wouldn’t fault or change what was done.

[(Hathor in cow form being worshipped from a solar barque) If you’re interested in learning more about how museums design and execute exhibitions like this while maintaining a safe environment for fragile artifacts, I did an entry about curation and conservation here.]

[This is one of my “oh, I know her!” artifacts, a composite metal statue of what is usually held as a mongoose or an otter with a solar disk and protective uraeus on its head from either the Late or Ptolemaic Period. Personally, I tend to be on Team Mongoose. Mongooses are more native to Egypt than otters (of which there are several species from other parts of East Africa); and the goddess Mafdet, one of whose forms is a mongoose, is a protector of Ra’s solar journey between the Waking World and the Duat (she is the Piercer of Darkness), so her wearing the uraeus disk is appropriate.]

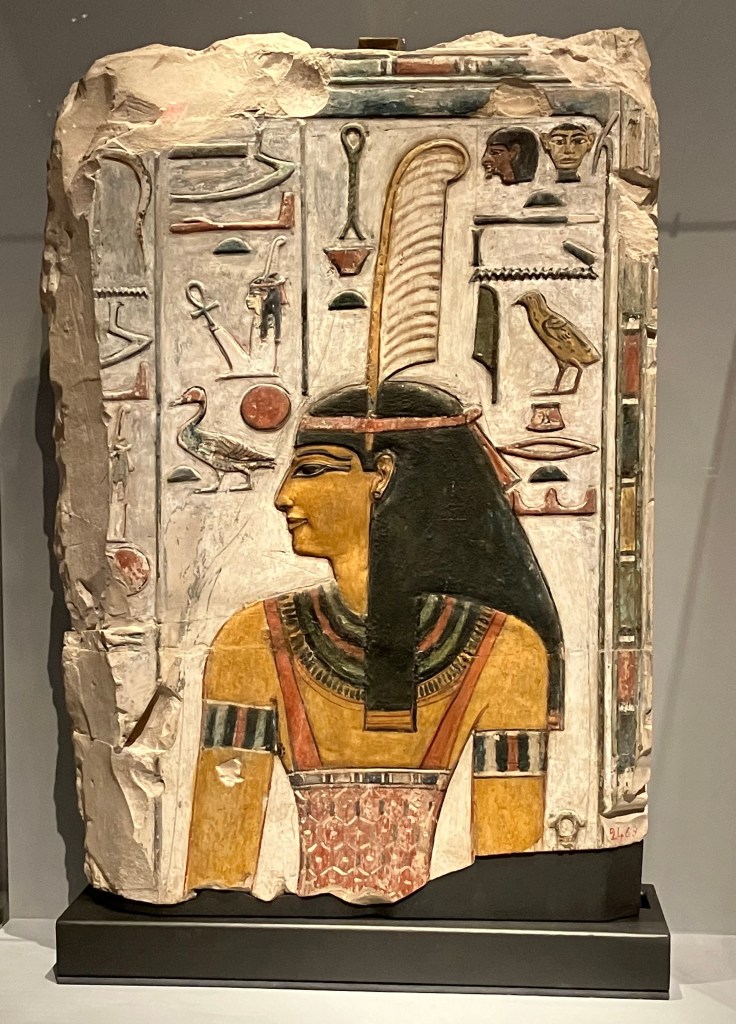

[Speaking of the daughters of Ra, there was also this stunning limestone fragment of Ma’at from Seti I’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Look at those colors!]

Moving on from Ra and his sky buddies, but continuing with the theme of those who defend the king of the gods on his nightly journey below the horizon, you’ll never guess who was around the next corner…

[Hai, mortals. You probably thought they’d just leave me out, but here I am enjoying a delicious banquet provided to me by Nakht the scribe. (New Kingdom)]

Tucked away against the far right wall was Set’s nook, and while he didn’t have the most impressive group of pieces, they did demonstrate his many forms as you can see in the picture below where you can see him in his hippo form, his semi-human hieroglyph, and in his full sha form. His wall infographic also did a good job of explaining his complexity as both a destructive and protective force in Egyptian cosmogony.

[Although I did have to hear this tour guide say that he was “the ugliest god,” and generally massacre my boy to this gaggle of old people. I told him not to listen to her… (Was-scepter with sha face, Middle Kingdom)]

But Set shares his nook with a few serpent deities, one of whom, Heneb, I thought I didn’t know. This in of itself wouldn’t be surprising, Egypt had an almost inexhaustible supply of snake gods, but I couldn’t find any mention of him anywhere when I got home. So, I worked backwards. The Met’s description of him says he’s associated with Herakleopolis, but I couldn’t find any mention of him in gazetteers of the city. But you know whose biggest temple was in Herakleopolis? Our buddy Nehebkau, the walking snake god par excellence. So I don’t know exactly what’s going on here…it’s possible that Heneb is an alternate name for Nehebkau (not unheard of for an Egyptian god, particularly one as old as Nehebkau). Or the museum transposed the letters in his name by accident from Neheb to Heneb, as the god’s name is sometimes written as Neheb Kau—which I’m not even criticizing because I did something similar myself on my first pass of my Nehebkau entry). Or Heneb is a minor secondary snake god of Herakleopolis that I couldn’t track down. Any which way, interesting.

[“Heneb” (R) from the Late Period; with a Ptolemaic amulet of an armed deccan serpent god (L), who were sometimes conflated with Nehebkau by that point in Egyptian history]

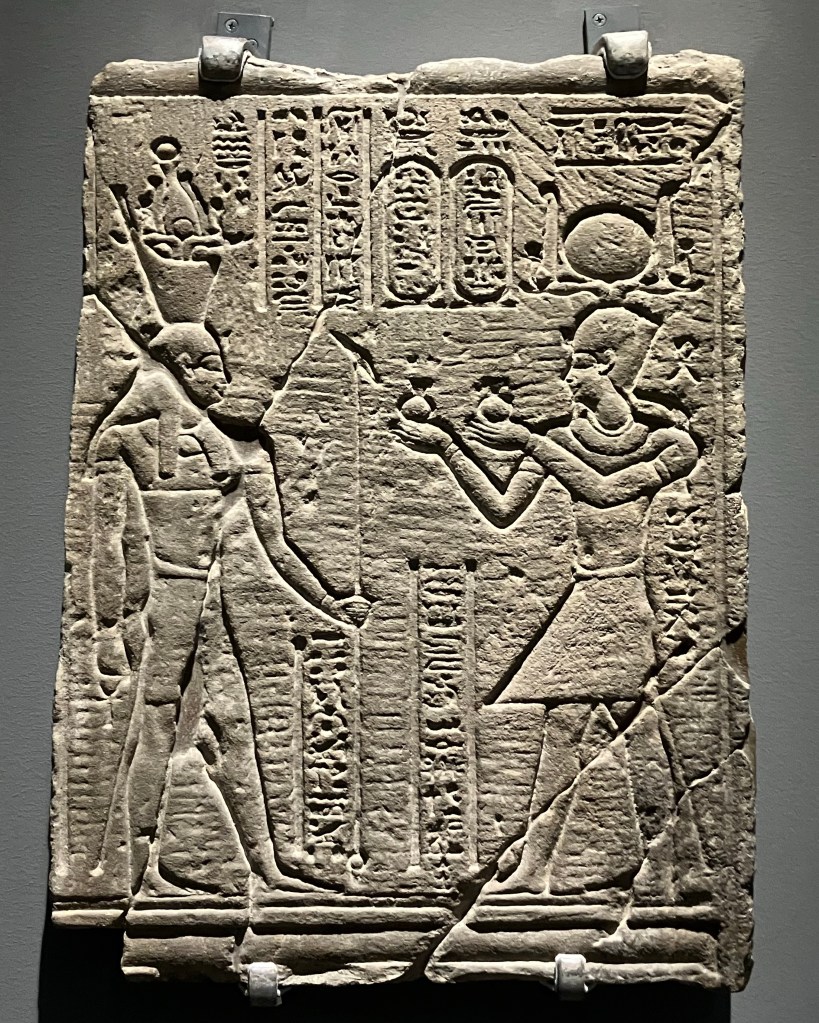

The large sandstone pediment below from the Meroitic/Nubian Period is full of Nubian symbols translated into Egyptian visual language during their dynastic control of Egypt, some of which we’ve talked about before. The middle ram deity is Amun, who, as a solar god, was thought to live in Nubia (the east) because that’s where the sun comes from. The ram even has Amun’s traditional feathered crown, accentuated with a solar disk and two uraei. The lion gods on either side of him are unidentified by the Met, but could very well be the Nubian-Egyptian god Dedun, “He Who Presides Over the Nubians,” who was sometimes depicted as a lion. The lions, whichever gods they are, are wearing the elaborate hemhem crown, which was first associated with Egypt’s Nubian rulers.

[Architectural element from a temple, depicting lion and ram deities, Meroitic Period (late third century BCE)]

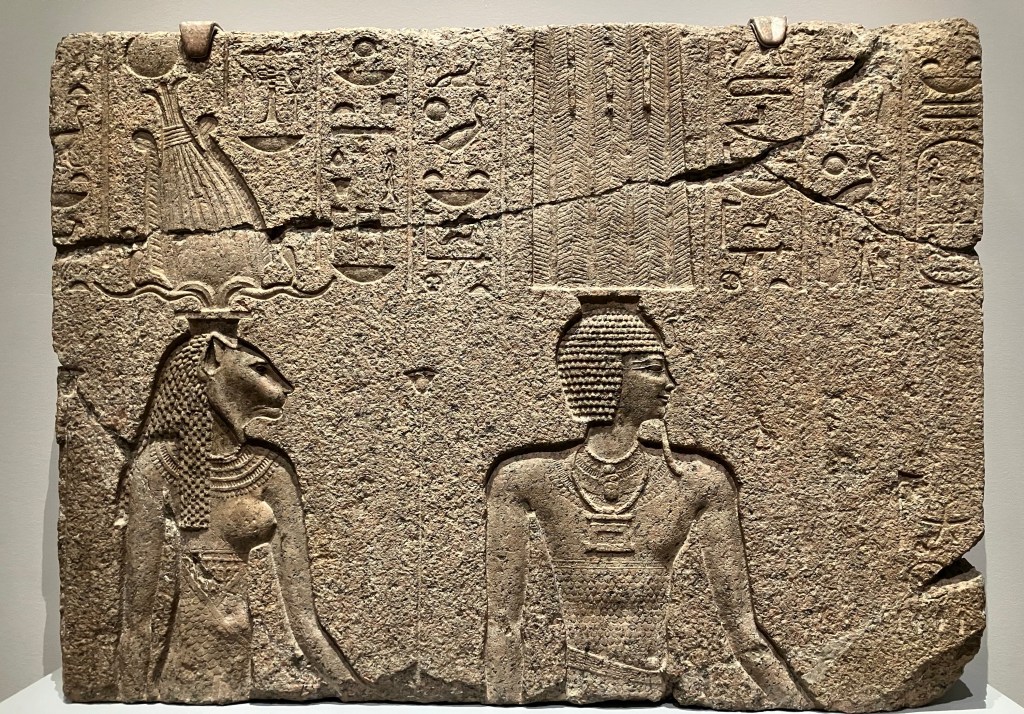

But the Nubian gods, like the hemhem crown, survived the demise of Kushite control of Egypt, and both come up often in Ptolemaic and Roman Egyptian art. You can see this in the Ptolemaic sandstone piece below, which depicts Anhur, a local war god from Abydos syncretized with the wind god Shu, with his wife, Mehyt, a Nubian lioness goddess (she is wearing a horned iteration of the Atef crown that was also popular in the later eras of Egyptian history). In an iteration of Sekhmet’s origin story, Mehyt takes the place of Sekhmet and is the lioness terrorizing humanity on behalf of Amun-Ra. Anhur, also considered a hunting deity, takes the place of Thoth in the other version, and is instead the god who tracks Mehyt to Nubia and subdues her through divine marriage.

[Relief of Mehyt and Anhur-Shu, Ptolemaic Period]

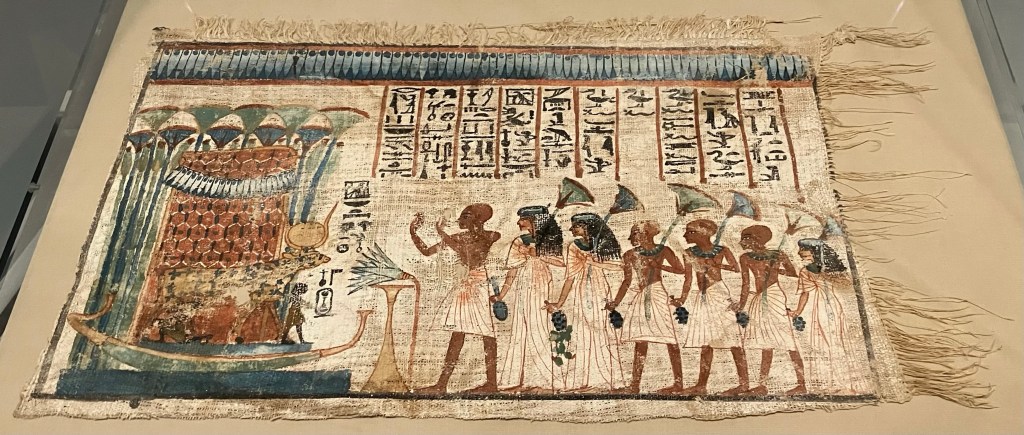

[Stela of Tjenetdinetiset and Djedbastet receiving water from a tree goddess

(Third Intermediate Period)]

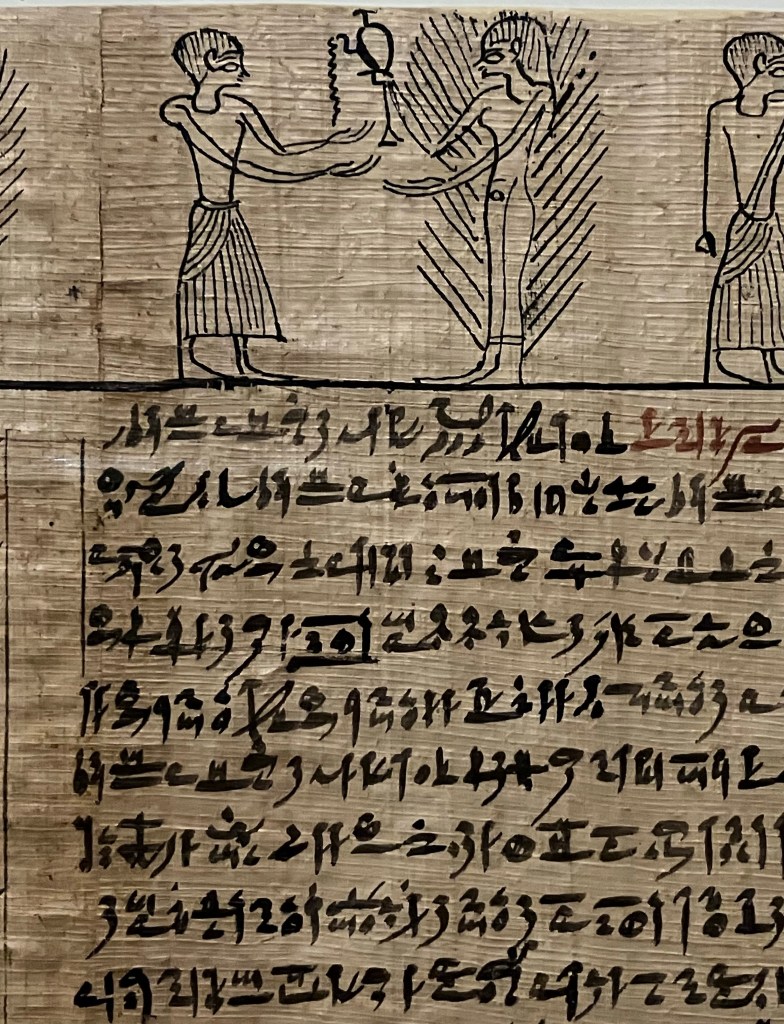

I loved the wood piece above of a tree goddess giving water to an Egyptian couple, in part because it is a rare front-facing depiction of an Egyptian deity. The Met placed it in the sky goddess Nut’s section, but admits that this could easily be Hathor or Isis, especially given Hathor’s epithet as Lady of the Sycamores. Compared this with a similar depiction of a water-giving goddess from the Book of Coming Forth from the Met’s regular Egyptian collection below.

[Papyrus copy of the Book of Coming Forth by Day, Ptolemaic Period]

[Moving on… oh, my…]

The next room of the exhibition is unavoidably dominated by the fertility god Min, and more specifically one of the three famous Naqada III Min colossi from the predynastic town of Qift (Coptos) in Upper Egypt not far from Ombos/Naqada. Qift was Min’s earliest and largest cult center, and the colossi were first discovered by aforementioned Naqada archeologist, Sir William Flinders Petrie. This is Colossi II, arguably the most intact of the three, and it’s hard to make out in my picture, but the side of his right leg has Min’s hieroglyph carved into it, as well as conch shells and swordfish saws, early symbols that connected Min with the fertility of the Nile.

[And the colossus from behind, tee hee…]

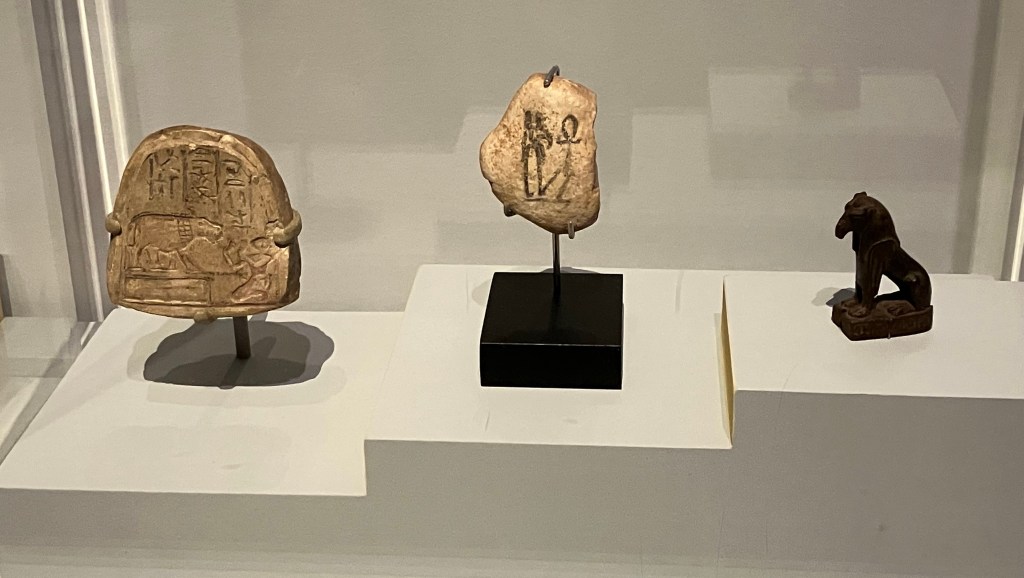

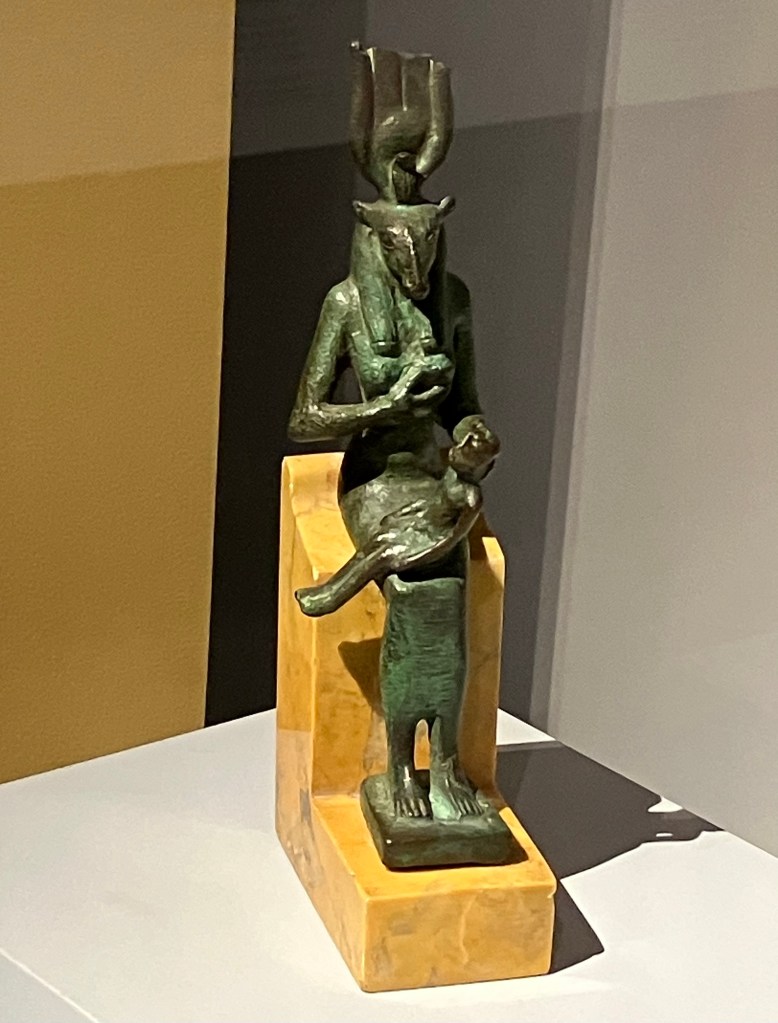

The final above-horizon room of the exhibition is mostly smaller statuettes and amulets, but there are some really delightful gods in here, especially as many pieces are from the Late or Ptolemaic periods, where syncretism had really begun to consolidate the Egyptian pantheon.

[Like this Isis Lactans, which shows her as the triune goddess Isis-Hathor-Selket, nursing her son Horus-Harpocrates]

[Or this little guy who’s probably a syncretization of Anubis (head) and Bes (the shortened body). Look at his little snakes!]

[Or, speaking of Bes, this truly impressive hybridization of Horus the Elder, Bes, Min, and possibly Khnum]

The Min colossus wasn’t the only Egyptian artifact to make the internet meme rounds that I saw in this exhibit, though. Once we entered the Duat space, I found this wood and plaster Anubis who was famous a few years ago for his “Imma need y’all to calm down” gesturing. Sadly, in his own parlance, he’s likely simply performing a funerary rite.

[Statuette of a canid god, probably Anubis (Ptolemaic Period)]

[Falcon-headed coffin with Osiris grain mummy (Late Period)]

Obviously, the Duat hall was dominated by Osiris, but I found the above grain mummy one of the more interesting artifacts surrounding the god. Made as an offering for the Khoiak Festival celebrating the god’s death and resurrection, the grain mummy recognizes Osiris’ role as a god of vegetation and agriculture. The grain mummy emerges into new life from the coffin of death, represented by the falcon-headed death god Sokar, with whom Osiris was often hybridized. The other most fascinating Osiris artifact here was a wood reliquary fetish meant to represent the hieroglyph of Ta-wer, the nome of Abydos, Osiris’ cult center, which eventually evolved into being a representation of a container meant to hold the god’s head. Neither of these were objects I had ever seen before, and they added some nice context to the other more traditional Osiris statues, etc.

[Model of the Ta-wer emblem (New Kingdom or later)]

Oh gosh, there were so many other things that caught my attention! A harp-playing Bes; an ear stela dedicated to Nebethetepet, the Hand of Ra and the Lady of Offerings; a Taweret magic wand; Nefertem making an appearance; an Isis-Selket that looks like a Human Centipede; angry rabbit goddesses of the Duat; gods holding more monkeys than they know what to do with; Geb wearing a crown that looks like he just threw a bunch of crowns in a deshret and called it a day… I could go on. But I hope that I’ve shown that Divine Egypt really tried to hit as many godly bases as it could in a limited space. For every Horus and Sobek, there were plenty of Anhurs and Henebs(?) to go around, making it hard not to find something new to discover. So if you’re in the greater NYC area, you should come down and check it out. Have some fun, learn a little, and be embarrassed by Min’s enormous phallus with complete strangers! Culture!

[Okay, here’s Geb (L) wearing what is sometimes called the Geb crown, which, from what we can tell, is the Atef crown with ram’s horns and a solar disk inside a deshret crown—the Met describes it as “unwieldy.” But as he comes off more like he’s Carmen Miranda in a fruit hat, one has to wonder just how many wine jars Ptolemy XII Auletes (R) has been offering him…]

Leave a reply to Ghost Fluff Cancel reply