Because I thought that with Daughter of Scorpions’ publication this spring, I was finally leaving the historical ancient Mediterranean behind (…we’ll see—I’ve been having intrusive thoughts recently about a fifth God’s Wife book…), I’ve been reading a bunch of other people’s Rome-adjacent novels. In February, we talked about two of them, Thornton Wilder’s The Ides of March and Zora Neale Hurston’s The Life of Herod the Great, but I thought that we’d do another paired look at two more that I finished this fall: British author Evelyn Waugh’s novel about the mother of Constantine, Helena, and American author John Williams’ National Book Award-winning novel, Augustus, about our other favorite intrusive thought.

[You should all be grateful that I’m considering staying dead in the next book, if she decides to actually write it…]

Arthur Evelyn St. John Waugh (1903-1966) is probably the one that more of you are familiar with as the author of Brideshead Revisited (1945) and The Loved One (1948). His novel Helena (1950) is less well known than most of the rest of his oeuvre, but it was his personal favorite, and any time an author singles out their favorite book in their bibliography, it makes me take notice. Waugh’s father was a publisher, but his family was well off enough to give him a private education and he earned a scholarship to Oxford (which he would eventually lose before graduating through an almost complete lack of interest in his studies. He would work (grudgingly) as a teacher until his first novel, Decline and Fall (1928), brought him almost instant acclaim, and moved him into the typical 20th century authorial milieu of journalist-novelist for most of the rest of his professional life.

In the early part of his career, Waugh was associated with the so-called Bright Young Things, the British Bohemian circle in the 1920s, who he would eventually satirize in his novel Vile Bodies (1930). The Bright Young Things were known for their nonconformist approach to drugs and gender relations, holding wild costume parties and scavenger hunts through nighttime London, and otherwise throwing off the perceived strictures of late Edwardian/Georgian English society. Many young writers and artists like Waugh were associated with the group, of course, but a lot of the Bright Young Things were simply bored younger members of the aristocracy and their socialite hangers-on. This was in no doubt some of the attraction for Waugh, who had the very English upper middle class weakness for the perceived glamour of the nobility and gentry. You can see this attraction, nostalgia, and disillusion with the fast aristocracy in Brideshead Revisited. He would experience great success with Brideshead, and Waugh would retain his love of the Bright Young Things’ high life, if not their politics and social mores long after he had left them behind, which left him constantly short of money up until his death.

Waugh’s falling out with the Bright Young Things was in part precipitated by his divorce from his first wife, Evelyn Gardner (a lord’s daughter, btw) in 1929, which in turn eventually led to an almost complete spiritual reversal that culminated in Waugh converting to Catholicism a year later. Waugh would then spend the rest of his life seemingly trying to validate every joke you’ve ever heard about adult Catholic converts, like railing against Vatican II and the vernacular liturgy while telling the ecclesiastical courts that his divorce shouldn’t count so he could marry a Catholic peeress this time around (his second wife, Laura Herbert, was a descendant of our much-mentioned Jacobean Pembrokes). And this is what fueled Waugh’s novel Helena, a historical fiction quasi-hagiography of the mother of the emperor Constantine, who supposedly influenced his conversion and that of the Roman Empire to Christianity, and the Early Church saint who supposedly discovered the remains of the True Cross. Just in that, you can sense why this novel might mean so much to its deeply converted author.

The historical Helena is an extremely obscure figure; not only are we unclear about her family lineage, we’re not even sure where she was actually from. Most historians think that she was born from the lower classes in Bithynia (northern Turkey), in part because the city of Drepanon being renamed Helenopolis after her death and its proximity to the city her nephew, the emperor Julian, renamed in honor of his own mother. But Constantinople has also been thrown out as a possibility, in part because we also don’t know how she met Constantine’s father, Flavius Valerius Constantius Chlorus (Constantius I), himself an Illyrian soldier who rose through the ranks to become the emperor Maximian’s political heir. Helena’s low status is often inferred by Constantius setting her aside to marry Maximian’s daughter, Theodora, with some suggesting that she and Constantius had never being formally married in the first place. Ambrose of Milan, writing in the 4th century, goes so far as to claim that Helena was a stabularia, a stable-maid or hostler’s daughter. This is wild from a bishop, but Ambrose might be employing a common hagiographical technique where the saint in question is born of extremely high or extremely low social rank to emphasize the importance of their religious transformation (i.e., a highborn person is humbled by God before they can become holy, or a lowborn person is raised up by dint of their holiness in God).

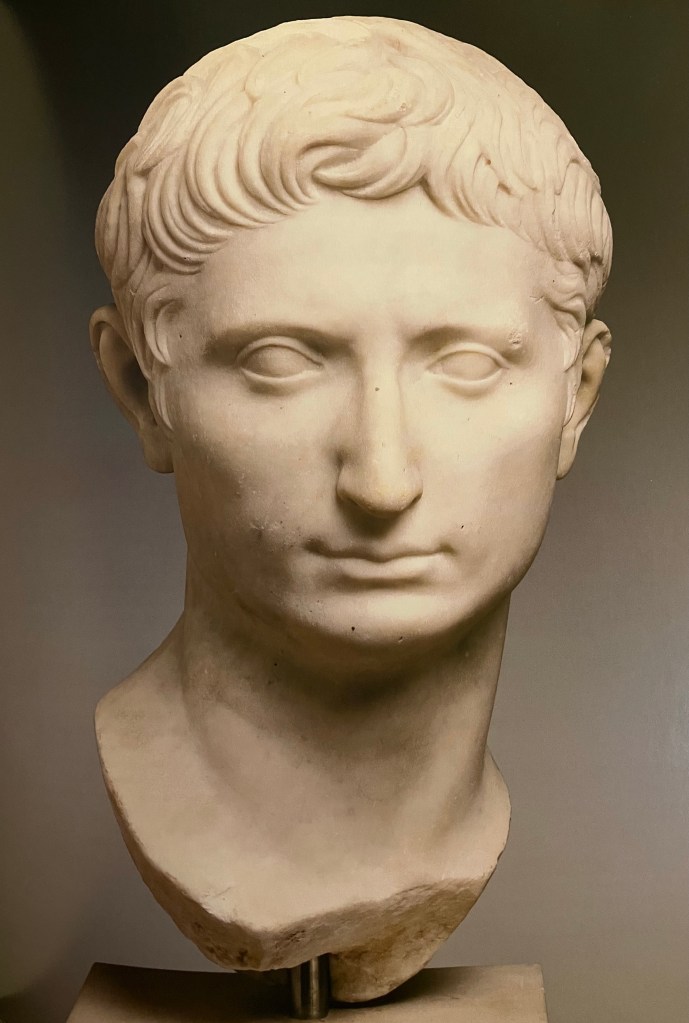

[Capitoline statue of Helena]

In the opposite direction both geographically and socially, but adding to the confusion, the 12th century Welsh/English chroniclers Geoffrey of Monmouth and Henry of Huntingdon—likely in a bid to beef up the credentials of early Christian Britain—claimed that Helena was actually the daughter of the Welsh king Coel Hen (possibly your Old King Cole of nursery rhyme fame), and was therefore a princess, albeit in an obscure part of Roman Europe. It is frankly the least likely scenario, but also the one with perhaps the most fascinating potential, and was obviously a lure to a British novelist like Waugh. So, this is the folkloric path he takes: Helena is an English princess living in Colchester (Essex), who by chance meets Constantius Chlorus, marries him, and gives birth to the future emperor Constantine, before being set aside by her husband, converting to Christianity, and finding the resting place of the True Cross in her old age while on pilgrimage in Jerusalem. An epic life by almost any measure, and one that definitely feels ripe for a sweeping historical novel.

Unfortunately, arguably the biggest flaw with Helena is in its author. Waugh is not historical fiction novelist, and I think it shows in Helena. I would never suggest that authors cannot experiment with different genres, but very few can do so without leaving traces of their “home” genre on the less familiar one, in Waugh’s case, contemporary social satire. This is in part because all literary fiction genres (and nonfiction literature as well) have their own tropes and earmarks that are not always apparent to non-practitioners, that subtly flavor the style of the story and leave “tells” if absent. Think of how I talked about Agatha Christie’s “home” in drawing room Golden Age mystery writing colors her writing even in her ancient Egyptian play, Akhnaton. For historical fiction, one of the traditional elements of a successful novel in the genre is typically a deep, lived-in sense of time and place. Historical fiction can covertly be about the author’s contemporary situation (indeed, it often is), but that should never take away from the story’s context. Waugh’s 3rd century is only surface deep, and like Christie’s theater Egyptians, his Romans and his imperial protagonist all are 20th century Britons wearing historical costumes.

This sometimes works for the ostensibly English Helena, and particularly in the early half of the novel, I actually rather enjoyed it for her (it gave her a sort of genre-skewering verve that reminded me of Flora Poste in Cold Comfort Farm). But when you realize that everyone is kind of like that, it feels less like clever characterization and more like Waugh has trouble writing non-Anglo-American characters. In the beginning, Helena has a sort of “Roman problems require English solutions” attitude coupled with an equally English keep-calm-and-carry-on approach to the chaotic world of the late Roman Empire, all of which is made more likable by an impish Celtic disposition to everything. In short, she is thoroughly British. Contemporary reviews of the novel found her “slanginess” grating, but I found it at least an interesting, if unconventional, choice on Waugh’s part. Part of my problem is that gets flattened as the novel goes on, and Helena becomes much less interesting as a character as the novel progresses.

Even this might have been a subtle meta-commentary on the cultural homogenization of imperial Rome, or Helena’s own disillusionment as she is separated from her husband and son, but my main beef with Waugh and Helena is it is too damn short for the scope of the story it wants to tell. At somewhere between 215 and 249 pages, depending on your edition, you’re just not going to get the immersion in a lost perspective that is also a historical fiction genre touchstone. Waugh has so much to get through that he skips over Helena’s conversion experience, the thing you’d think a maniacal new Catholic would be most focused on. Like, one minute she’s “intellectually interested but questioning” Christians, and the next she’s going to church constantly and known by everyone for being piously Christian. You never see her accept anything directly. The only reason it doesn’t feel like it comes completely out of nowhere is because you, dear reader, know that she has to convert at some point. The slangy girl of the beginning just vanishes, and Helena just wanders about outside the imperial plot until it’s time to head to Jerusalem.

This may be Waugh piously not wanting to invent a conversion experience for a real saint—I couldn’t find any text that speaks directly of when and how she became a Christian—but then what are we doing here, bro? Why bother writing a historical fiction story if you don’t want to, you know, fictionalize? You made up a meet-cute for her and Constantius where they’re the ones who come up with stabularia and Chlorus nicknames for one another (which I liked, it gave their otherwise opaque relationship depth), but you won’t, say, use your own conversion to put us in your heroine’s shoes? It just comes off as pulling your punch at the last minute. There are shiny bits and pieces to really like in Helena, the last page is Waugh at his most supremely evocative, but it’s all too uneven. The middle chunk between Colchester and Jerusalem feels like it’s mostly killing time, except for a wild and violent brief detour to Rome that seems to have come from a larger and more traditional Roman historical novel. I would have even accepted a slower story if I thought it was a good imitation or sendup of medieval saint’s stories, but I don’t get the impression that Waugh paid enough attention at Oxford to pull that off. I feel like I see what he was trying to do overall—I’m just not sure that the result is entirely successful.

[All right, enough about this stabularia. Time to talk about someone who (probably) wasn’t born in a barn…]

Our other author, John Edward Williams (1922-1994), is probably less well known to the average person on the street than Waugh, but he’s seen something of a renaissance recently and his handful of novels are coming around into fashion again. Born in Texas of the typical western American background of farmers and laborers, Williams, like the more posh Waugh, initially flunked out of college, but unlike Waugh, returned to complete multiple degrees after serving in World War II. He also, unlike Waugh, became a lifelong teacher and professor of writing and literature at several American universities, hence his smaller literary output. Currently his most enduring book is Stoner (1965), about the life of an ordinary assistant professor and a literary study of quiet, heroic failure (Stoner himself reminds me of Bjartur from Independent People, without the latter’s slight pomposity) that has been called by some critics possibly the “perfect novel.” Conversely, Augustus, his historical fiction novel about Rome’s first emperor, was arguably the most renowned in his own time, winning him the National Book Award in 1972.

Like Waugh, Williams was not considered a historical fiction writer, and Augustus, his last novel, was seen as a bit of a curve ball for him. Stoner and his other two novels were relatively contemporary stories about somewhat alienated young American men grappling with the life’s understated cruelties and futilities. And there definitely is a vein of that in Augustus, where in another slim novel of barely 300 pages, we follow Octavius from his boyhood just before Caesar’s assassination to the end of his life in Nola. In contrast to the mysterious Helena, we (theoretically) know a lot about Augustus, but to return to his literary preoccupation with struggle and futility, what Williams chooses to focus on is the arguably two great tragedies of the emperor’s life: his precarious and violent rise to power and the events that led to his daughter Julia’s banishment.

In choosing this less heroic angle, you might think that Williams is having a conversation with the Lives of the Caesars or the Annals, but in practice he’s dialoguing with two much more recent books. In form, to return to the aforementioned previous discussion we had in February, Augustus feels like a sequel to The Ides of March (1948). So much so that if I had read them closer together, they would be a much obvious compare and contrast pairing for an entry like this. Both novels are epistolary, using documents and letters to both add a patina of verisimilitude and distance the author from the narration, though Thornton Wilder’s Caesar is a lively participant in his story and we don’t hear directly from Augustus until the very end of Williams’ novel. I have some ambivalence about Williams’ choice that I’ll get to in a bit, but I acknowledge that this is arguably a solid characterization decision. Julius, as a writer, orator, and man with terminal Main Character Syndrome, is never/would never be content to let other people speak for him in life, and Wilder’s Caesar reflects this, as does his single, spectacular appearance in Augustus, where his breezy, clever, bossy letter to his niece Atia (Augustus’ mother) kicks off Williams’ book. Augustus as a historical and literary figure is less flamboyant than that, more content to let others speak (well) of him and using his posthumous Res Gestae cover the finer points of his achievements. All of this true characterization reflects in the end result: I really liked both novels, but, true to Julius, Ides is a much more “fun” read.

But when it comes to characterization more broadly and content, Williams is more clearly responding to Robert Graves’ I, Claudius (1934). The introduction to my copy of Augustus, written by classist Daniel Mendelsohn feels almost agog at the thought that Williams thought to write Julia Augusti and Livia Drusilla with a modicum of more restraint than the unrepentant slut and wicked poisoner they are in Claudius (which I adore in spite of this, for the record). Having spent a decade and counting doing the same, I’m less blown away by the concept, but Williams and I are on the same page. With his Julia in particular he does some really good work, which only falters a bit because Williams can’t quite write women characters with the same emotional immediacy that he can from the male perspective. This is compounded by the choice that Julia’s diary, our main pov for Book II of Augustus, is all told by her in flashback from her banishment on Pandateria, which allows her to detach from her emotions rather than be in them.

And I think that postmortem detachment from the action, which the slim Book III of the novel—finally from Augustus himself—shares, also allows Williams, not unlike Waugh, to pull his punch at the last second. Williams’ Augustus is not heroic, but too often he lets Octavius act like a victim of circumstance, which feels disingenuous, too. Book I ends with a letter from one of our main povs, Maecenas, wearily rattling off to Livy all the terrible things Augustus did at the end of the civil war (killing Caesarion and Antyllus, etc) in list form, while also claiming that Augustus would have spared Cleopatra’s life (right…). And this is after Williams constructs this whole scenario where the proscriptions were mostly Antony’s fault and Augustus basically had to go along with them. Look, like Williams, I don’t care for Mark Antony, but this is a bit much.

But this is the great conundrum Octavius presents to a novelist. It is so easy to fall into the trap of making him a coldblooded monster or a well-meaning dupe of fate (Robert Graves manages to do both at the same time occasionally). Williams allows Augustus to be a man without entirely letting him be human. Having spent so much time writing him (at much greater length) at all the stages of his life that Williams hits, I can attest to the complexity that lies at Augustus’ heart, but I think you have to let that whole flower unfurl without pruning bits off in one direction or the other. Julius Caesar is a blast to write because he’s a fae king; Octavius is the challenge because he’s a chimera, both Shakespeare’s knave of fortune and Rome’s Pater Patriae. To me, the key is that he is always both. That’s why I use all of his names throughout my God’s Wife books: to treat Octavian as erased when Augustus is born is to miss half the point. If one is allowed to glimpse the venerable Augustus in the fatherless boy Octavius, you must accept that when he is the feeble old man supposedly under Livia’s murderous thumb, he is still the Octavius of the proscriptions. I allow Augustus a lot of space for redemption in my books, and I feel like

Williams is even more permissive than I am, which is

surprising to me.

Ultimately, Augustus is a far better book than Helena (though I respect the latter for some of its innovative choices), but as much as I enjoyed Williams’ novel, I think that those of us in his future have it right and Stoner is his best book. I rated Augustus a little higher on Goodreads, but some of that is because I have long-standing parasocial relationships with most of the Augustus “speaking cast” (Maecenas, Agrippa, Julia, Horace, Ovid, and of course Augustus himself) and that adds some extra ephemeral enjoyment for me. Stoner is a tighter story, and I can see exactly what critics are seeing when they call it “perfect,” but it is also pretty depressing in a way that makes it difficult to imagine rereading right away. Conversely, I rated The Ides of March and Augustus equally high, but Ides is a lot more fun than the also slightly depressing Augustus. But one thing Wilder, Williams, and Waugh (what a law firm name!) have in common is that they’re all renowned prose stylists who each bring a little something different to the ancient historical fiction table, and are definitely worth checking out. Add Hurston’s wild hot take on Herod and the classic Suetonius-driven batshittery of I, Claudius to the mix, and you won’t even blink at the gods showing up in the flesh in my books😉

Leave a comment