It might be 85 degrees outside, but technically it is almost fall here in Pittsburgh, and about time for us to return to the Carnegie Museums and see what they have going on. I haven’t been down to the Science Center yet since their big name change/reopening, in part because they’re cycling through all of the traveling exhibitions I ranked lowest in the interest survey they sent out last year, but here’s hoping for Tut and some other history ones next year🤞

[Speaking of Egypt…]

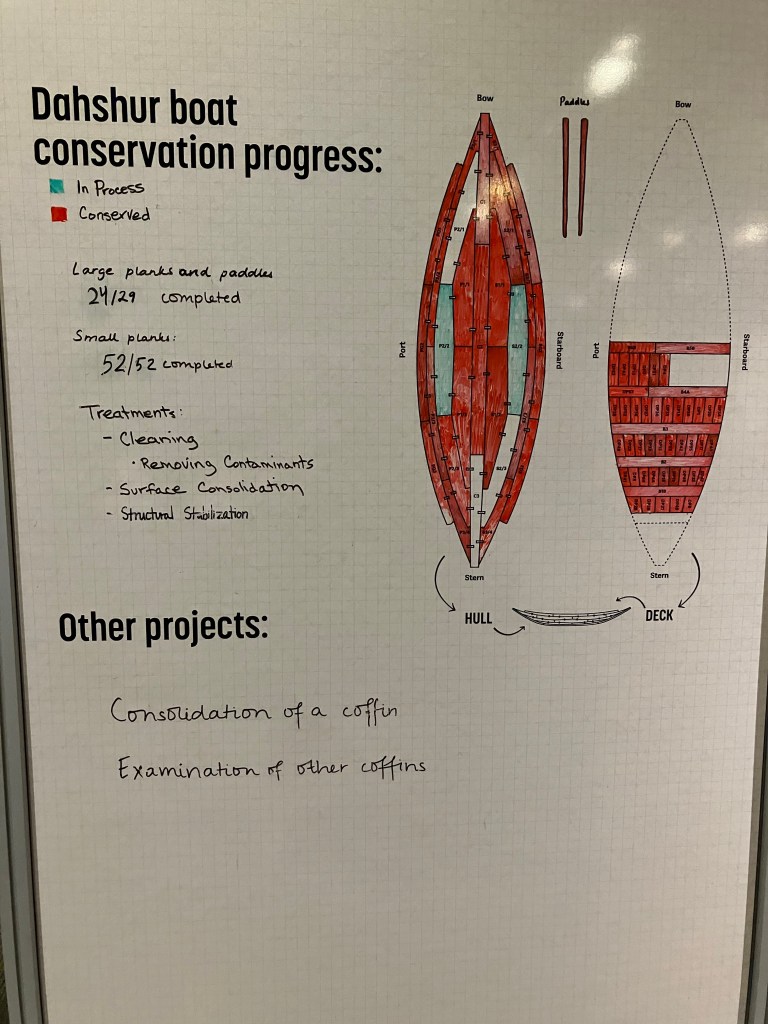

At CMNH, the Walton Hall of Egypt remains closed, and the filler exhibition, The Stories We Keep, has ended as well—which hopefully means that the hall is planning to open soon—but I’m guessing not until at least early next year since I haven’t heard any updates. They’ve also stopped adding any new Egyptology pop ups for the Third Floor since the one on Siwa, which is shame, but also hopefully a sign of completion for Walton. The last time I lapped The Stories We Keep two visits ago, they were almost done with the Dahshur boat, which I believe is meant to be the centerpiece of the renovated hall, so that’s another good sign.

[I was afraid that the conservation team might have felt like zoo animals working out in the open during TSWK’s run, but several of them have said on social media that they’ll actually miss it and talking with museum visitors, so I’m glad it seems to have been a positive experience for everyone.]

Another exciting development in progress over at CMOA is that the curator staff is already starting prep work for the next Carnegie International, set to open next May (I can’t believe it’s already been four years since the last one…time has truly lost all meaning since the pandemic…). Because they’re already closing off gallery spaces, that leads me to believe that the crates being kept in the Hall of Architecture’s semi-official storage hallway are in fact International pieces, rather than anything else. The theme has not been announced yet, but the curation team is promising that this will be the “most collaborative and far-reaching” International to date.

[Stay tuned!]

The modern International is a good segue way into what I want to talk about today, though, which is the two major exhibitions running at CMOA presently, which are Fault Lines: Art, Imperialism, and the Atlantic World; and Black Photojournalism. The contemporary International is working hard to commit to a broad range of modern international art, both in terms artist and medium representation, which, as I’ve tried to highlight over many entries, in of itself is a representation of CMOA’s ongoing efforts to expand the meaning and inclusion of Art in its collection. Modern museums that are willing to engage with the current ethical institutional debates have been (in a good way) stretching the definition of “art,” not only in terms of old masters versus modern artists, but also in terms of questioning what constitutes art and examining how we arrive at the answer to that question.

As I briefly talked about in my write-up for the exhibition book last December, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston was grappling with this in their exhibition, Making Her Mark, which focused on women’s art in Europe from 1400-1800. The expansiveness here came from not only including the very few women who were able to become professional artists in the traditional museum arts like painting and sculpture, but those who worked in both private and professional spaces in areas such as embroidery, general fashion, cabinetry and upholstering, commercial ceramics, and book design and illustration—areas often labeled “crafts” instead of “true art” for reasons of both class and gender. When most fine arts museums have sections for Chippendale furniture and Greek kylixes, the question of why these women’s contributions are “not real art” becomes much more cloudy than even the most dismissive critic might believe. Hence why many museums are radically changing their approach to their collections and how pieces are displayed and contextualized to the public.

[We also talked about this in my last museum entry from March when discussing Gala Porras-Kim installation in CMOA’s Forum Gallery series.]

This is becoming an even more imperative conversation here in the US as the current administration is threatening to intervene in how and what the Smithsonian is displaying in its museums, particularly in the Museum of American History and the Museum of African American History and Culture. As with those institutions, what both Fault Lines and Black Photojournalism, and exhibitions like them, are attempting to present is not the negation of what many might consider “traditional” museum culture/curation, both rather an expansion. What Fault Lines’ curator, Dr. Marie-Stéphanie Delamaire, calls “art from absence.” When we look at a piece of art, what was happening around its creation? How would that have influenced what was made (or how? or by whom?). And just as Making Her Mark openly admitted its own limitations by being overwhelmingly unable to identify women of color who were working in the same mediums as the predominantly white women of its exhibition, how are marginalized people present or absent in what we display? How does that presence or absence shape how we perceive history and our present?

What even I was unprepared for was how well these seemingly separate exhibitions blended with one another and addressed many of the same questions. Fault Lines brought together a disparate group of pieces from across CMOA’s collection to explore the cultural interplay of the post-Colombian Exchange global world through the art produced by and for people in the colonial Caribbean, Mexico, and North and South America. And Black Photojournalism curated an extensive collection of professional Black photographers’ work published in and for the network of Black-owned and read publications from the postwar period through the 1980s—everything from major Black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier, to the first Black magazines like Jet and Ebony. This timeframe was of particular focus because in these times, Black people were rarely represented in mainstream publications, or only in relation to crime and violence, and Black photographers working for Black outlets could document a more expansive view of Black life. Again, that “art from absence” idea permeates both exhibitions. So let me walk you around both a little so you can see what I’m trying to explain.

The colonial Atlantic world depicted in Fault Lines begins with the territorial conquest of the so-called New World, primarily by Spain, and then branches out into how the trade empires of other European powers like England, France, and the Netherlands both shaped the culture of this new world and were in turn shaped by it. Because of the overwhelming perceived necessity of the Atlantic slave trade to the European colonial world in the western hemisphere, Fault Lines inevitably focuses a lot on race, an idea that existed before the modern imperial age, but became increasingly prominent as white Europeans had to create an ideological framework that permitted chattel slavery while simultaneously forming modern ideas about liberty and social equality.

This paradox would deeply affect the creation of this new Atlantic culture, where a stratified society of whites would rule over a substrata of biracial and non-white groups, ranked by how far away from the imported white ideal they were. White society would import European culture in ways that would both impress classical ideas of art and education on non-white residents, but the double-edged sword of Enlightenment intellectualism would also bring the ideals of the American and French revolutions, leading to the successful revolt the non-white population of Saint-Domingue and the establishment of the free republic of Haiti in 1804. Haiti’s successes would be through the ability of biracial Creoles and free Blacks to recognize their common cause with the enslaved and indigenous populations of Saint-Domingue rather than accept their relative privilege in a society that threw them a few crumbs in an attempt to earn their racial allegiance.

[Guillaume Lethière, Brutus Condemning His Sons to Death (1788)]

Guillaume Lethière (1760-1832) was an artist with several paintings in this exhibition, one of several Creole intellectuals highlighted, and like all of them, the son of a white man and a woman of color. Lethière was from Guadeloupe, another French Caribbean colony (one that remains an overseas department of France today), but spent a good deal of his adult life in France after his artistic talent was noticed by his father. One of his paintings in the exhibition, Brutus Condemning His Sons to Death, shows this European training with its intensely Neoclassical subject matter, as well as his close friendship with the Neoclassical artist par excellence in France, Jacques-Louis David.

[Guillaume Lethière, The Oath of the Ancestors (1822)]

But this isn’t to say that Lethière had fully capitulated to the dominant European culture. In another painting of his not in Fault Lines, The Oath of the Ancestors, he uses the visual language of the French Revolution to support the Haitian revolution that France was actively trying to put down. The two Haitian generals, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a formerly enslaved man, and Alexandre Pétion, a Creole officer, clasp hands over a tablet of the Haitian constitution and the broken shackles of slavery. Lethière meant this to show the cross-racial solidarity that ensured the success of the revolution, though as Wikipedia points out, it is a bit unsettling (and ironic if not intended, given Haiti’s historical struggle against the foreign supremacist forces that have crippled its ability to flourish as a nation since its independence) that the God Dessalines and Pétion look to for blessing is an extremely stereotypical, Blake-ian white God.

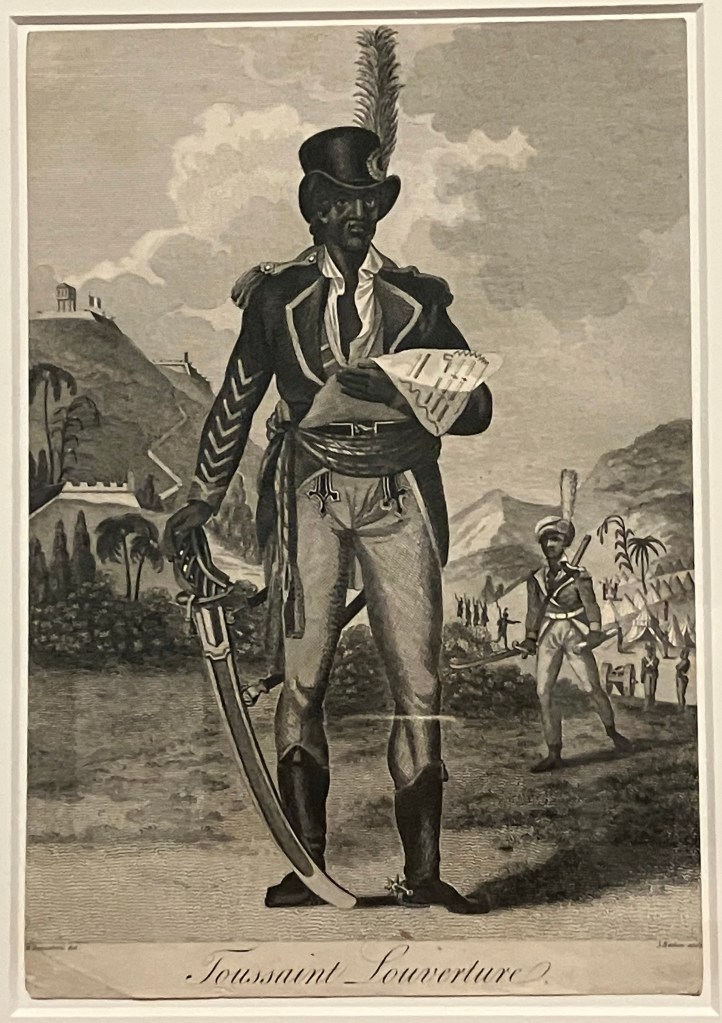

Racial attitudes also color the visual language surrounding the most significant figure in the Haitian independence movement, Toussaint Louverture (1743-1803). The exhibition had multiple engraved portraits of Louverture, who has no authenticated portraits from life, so his appearance changes in art between who is depicting him. Below, you can see that the Irish artist Marcus Rainsford, shows Louverture as an almost piratical figure, very dark-skinned with an undone shirt and a somewhat scavenged-looking uniform. On the other hand, the French artist Charles Monnet, depicts Louverture in the traditional full dress uniform of a French/Continental general, surrounded by other Black people wearing European clothing while receiving a message from Napoleon, delivered by a bowing courier. This courteous depiction of a man who was rebelling against the French might be due to Monnet’s own republican leanings (he was a famous illustrator of scenes from the French Revolution), and likely, if nothing else, reflects the ambivalent attitude of many French intellectuals toward the events in Haiti and Napoleon’s subversion of the French Republic into the Empire.

[Marcus Rainsford, Toussaint Louverture (1848). Interestingly enough, Rainsford was a British army officer who supposed met Louverture in 1799. He was then almost executed as a spy by the Haitian army, so one has to wonder if his position as a lifelong cog in the British Empire (he fought against the American Revolution, too) and his near-death experience in Haiti might have shaded his portrait of Louverture.]

[Charles Monnet, Toussaint Louverture Receives a Letter From Bonaparte (after 1802)]

[Pierre-Jean Boquet, View of the 40-day Fire on the Plantations near the Cap Français Plain, August 23, 1791 (1795)]

The Haitian Revolution and depictions of it have a lot in common with the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, a subject that, for obvious reasons, takes up a lot of space in Black Photojournalism. As the above print of Pierre-Jean Boquet’s depiction of the destruction of burned plantations in Haiti shows—displayed in the halls of the French National Convention in Paris as a reminder of the ruinous economic cost of the Haitian Revolution, no doubt—the other side will have its spin, and one bound to put your civil rights movement in the worst light. While mainstream white media focused on rioting and looting in American Civil Rights Movement, Black outlets focused instead on the humanization of Black life, though while not shying away from showcasing Black political organizing and solidarity.

[Moneta Sleet Jr., Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and family at home – Montgomery, 1956, (printed ca. 1970)]

[Jonathan Eubanks, Bobby Seale waving Free Huey Flag, 1968 (printed 1994)]

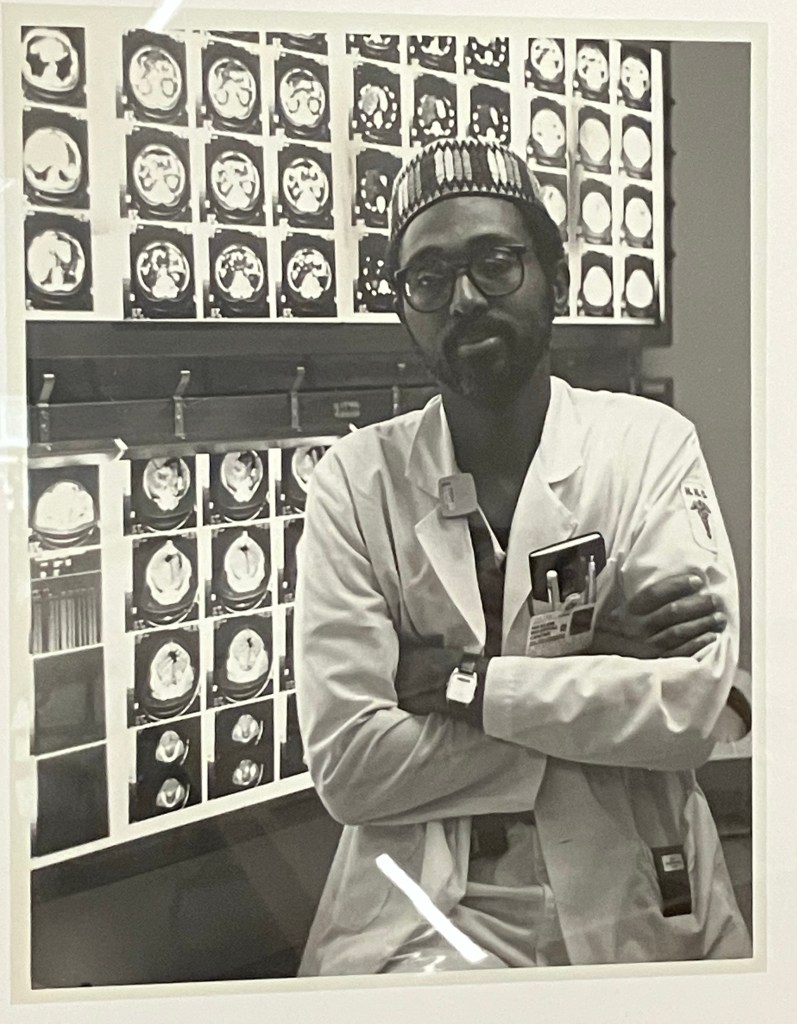

Depictions of Black excellence and achievement were also heavily featured in Black Photojournalism, as Black publications also served as a way to convey paths to success for young Black people not often otherwise shown in media. Alongside high school and college graduation ceremonies, I was drawn to this picture of Dr. Akamefula from the 1980s because it was so reminiscent of the first painting in Fault Lines of Francis Williams, the “Scholar of Jamaica,” a Cambridge-trained son of formerly enslaved parents. Both Williams and Akamefula are showing their achievements in fields stereotypically dominated by white people—Williams’ hand rests on an open copy of Issac Newton’s Principia Mathematica, showing his proficiency in mathematics, while Akamefula stands in front of brain CT scans, demonstrating that he is not only a doctor, but a brain surgeon. Despite these strong signals of white culture-coded success, neither man has abandoned his Blackness, as the scene outside of Williams’ white-coded gentleman’s study is of his native Jamaica, and for Akamefula, his wearing of a Pan-African kufi along with his traditional lab coat.

[Unidentified artist, Francis Williams, the Scholar of Jamaica (ca. 1760)]

[Unidentified photographer, Dr. Ajamu Akamefula (ca. 1985)]

Unfortunately for everyone else, white Europeans still managed to enjoy several uninterrupted centuries of political and economic dominance of Latin America and the Caribbean, which led to the acquisition of vast fortunes among the planters and the merchants and monarchies they supplied with their products. Europeans were introduced to a wide variety of exotic goods that would become status symbols for their consumers. And this is where Fault Lines works to draw our attention to the visual language embedded in “typical” art from this period, to show how these two halves of an interconnected colonial system intertwined. Sir Peter Lely’s portrait of Louise de Kerouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth, one of Charles II of England’s many mistresses, usually hangs a couple of halls over in the Scaife Gallery, but it’s being used in Fault Lines to illustrate how oranges were one of these new status symbols used to demonstrate wealth, as that is the tree the duchess is sitting in front of and the flower in her hand is an orange blossom. What’s interesting is that the extreme wealth being accumulated by non-royalty through trade in products like sugar and oranges meant that this sort of status symbol also begins to crops up in the portraiture of middle and upper class commoners like Mrs. Brinley, a woman living in the American colonies, where you can see an almost identical orange tree and pose to that of the duchess.

[Sir Peter Lely, Louise Renee de Penencoet de Kerouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth (ca. 1670-1680)]

[John Smibert, Mrs. Francis Brinley and Her Son Francis (1729)]

This democratization of wealth and influence led to an upheaval in white society as well, where, much as Edith Wharton’s buccaneer American heiresses would invade the 19th and 20th century British aristocracy, rich planters and their heiresses would use their money to buy and marry into established European aristocracies, as lampooned by the engraving below.

[Simon Ravenet, engraver, after a painting by William Hogarth, The Toilette (from the series Marriage a la Mode, 1745)]

Incidentally, as a result of their country’s briefly vast trading empire, Dutch still life painters became obsessed with exotic fruit and knickknacks during this period. Tropical fruits, exotic flowers, and Chinese ceramics replaced traditional still life objects as their patrons wanted even their non-portrait artwork to reflect their wealth, global outlook, and fashionable taste.

[This Jacob Fopsen van Es painting, Still Life with Lemons, Oranges, and Pomegranates (c. 1660), is a part of CMOA’s regular collection, and illustrates this point, where the deceptively simple design hides the extreme wealth of the subject (a bowl that is a blue and white Chinese china, filled with three different costly foreign fruits).]

[For the exhibit, the curators chose this more overtly opulent still life by Jan van Os (c. 1769). I know they’re not the most exotic fruit in this composition, but look at those glistening grapes! But also look at all the different tropical fruits on display here—even an ear of Indian corn for variety.]

[But my absolute favorite is this still life by either Willem Kalf or another artist working in his style, Still Life with a Chinese Bowl, Nautilus Cup Glasses, and Fruits (c. 1675-1700). This thing has it all: oranges, Chinese ceramics, a woven Persian tapestry or rug, an absolutely terrifying cup that is in the shape of a nautilus but has a goddamn anglerfish coming out of it… magnificent. Let people know that not only are you stupid rich, but that you’re also a bit of a gothy freak.]

Also unfortunately, it was not only luxury products harvested and fashioned by the enslaved people of the Atlantic world that were used to signal wealth in the white art of Europe during this period, but the enslaved people themselves, especially Black children, whom wealthy whites depicted in their portraits both as luxury items like the orange trees, but as something like an exotic pet. This is particularly driven home by works like Nicolas de Largillière’s portrait of an unknown woman in a Neoclassical setting apparently surrounded by her favorite pets: a parrot (another exotic signifier of wealth), a dog, and a young Black boy explicitly named as her slave in the paintings title. Or in the painting of Yale University founder Elihu Yale, his family, and an unidentified Black boy who belonged to one of them. The boy’s condition becomes even more poignant when you realize that he is standing in the foreground, working as a servant, while Yale’s grandchildren play in the garden in the background.

[Nicolas de Largillière, Portrait of a Woman and an Enslaved Servant (1696)]

[Attributed to John Verelst, Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child (ca. 1719)]

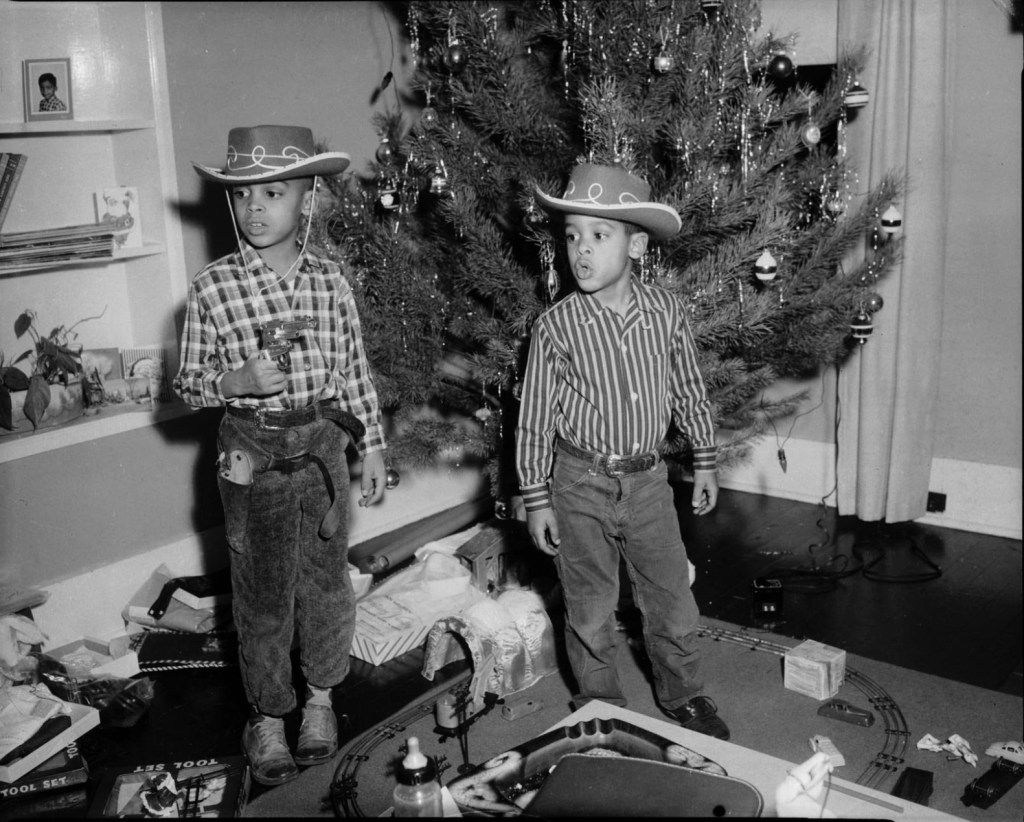

[Compare these pictures of Black child enslavement with a photo of Pittsburgh Courier photojournalist Charles “Teenie” Harris’s sons taken at a similar age, focusing on the playful joy and abundance of Christmas.]

As we saw with Francis Williams earlier, though, free Blacks of the Atlantic world were not immune to signifiers of the dominant white culture, especially those who benefited from being biracial, and therefore were able to access privileges not available to fully Black or indigenous people. See the portrait of Marianne Celeste Dragon/Dracos below. Marianne was daughter of a Greek merchant and free Creole woman in New Orleans, and while her portrait mimics the style of the portraits we saw earlier of Louise de Kerouaille and Mrs. Brinley, its more simplistic style belies the fact that Marianne’s mother, Marianne Françoise Chauvin de Beaulieu de Montplaisir, was a wealthy woman in her own right, and that the younger Marianne was being raised with all of the cultural benefits of being a rich Creole heiress in the Louisiana of this era. Even when taking cues from the colonial culture around them, non-whites were finding ways to make the white European cultural gaze their own.

[Attributed to José Francisco Xavier de Salazar y Mendoza, Marianne Celeste Dragon (or Dracos) (ca. 1795)]

Compare this to how Black Photojournalism shows Black women first bending white cultural signifiers, like debutante culture, into their own identity, then through the Civil Rights and Black Power movement turning female Black identity into something that demands its own place in the culture at large.

[Ernest C. Withers, Group of Debutantes (1953)]

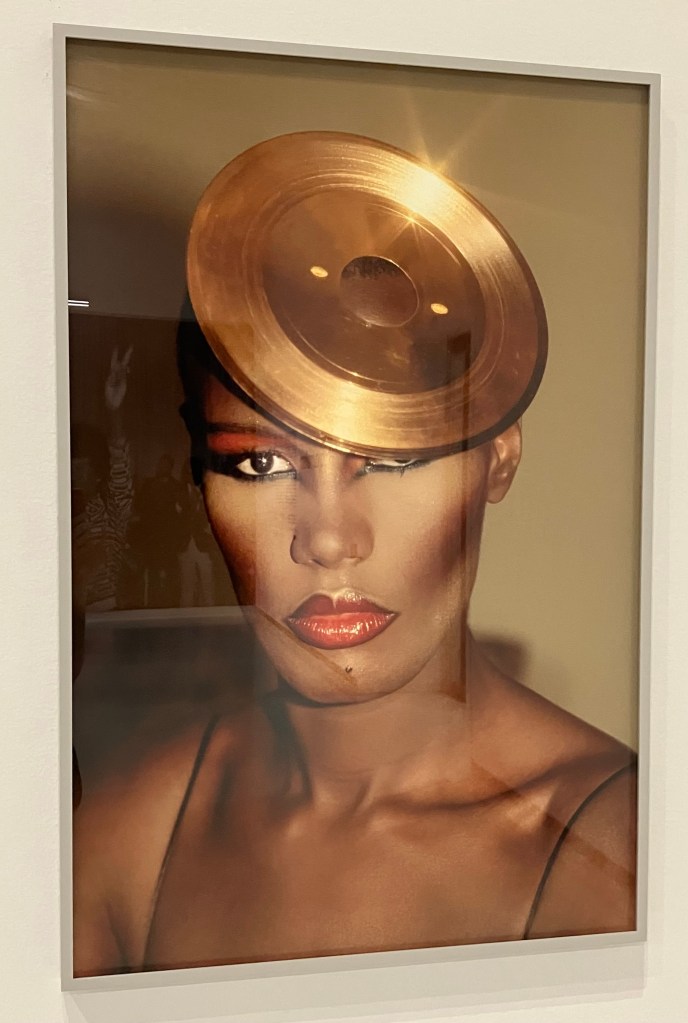

[Kwame Brathwaite, Changing Times (ca. 1973), as collaged by mixed media artist Liz Johnson Artur (2025)]

[And of course, the iconic Grace Jones, as photographed by Kwame Brathwaite (c. 1980)]

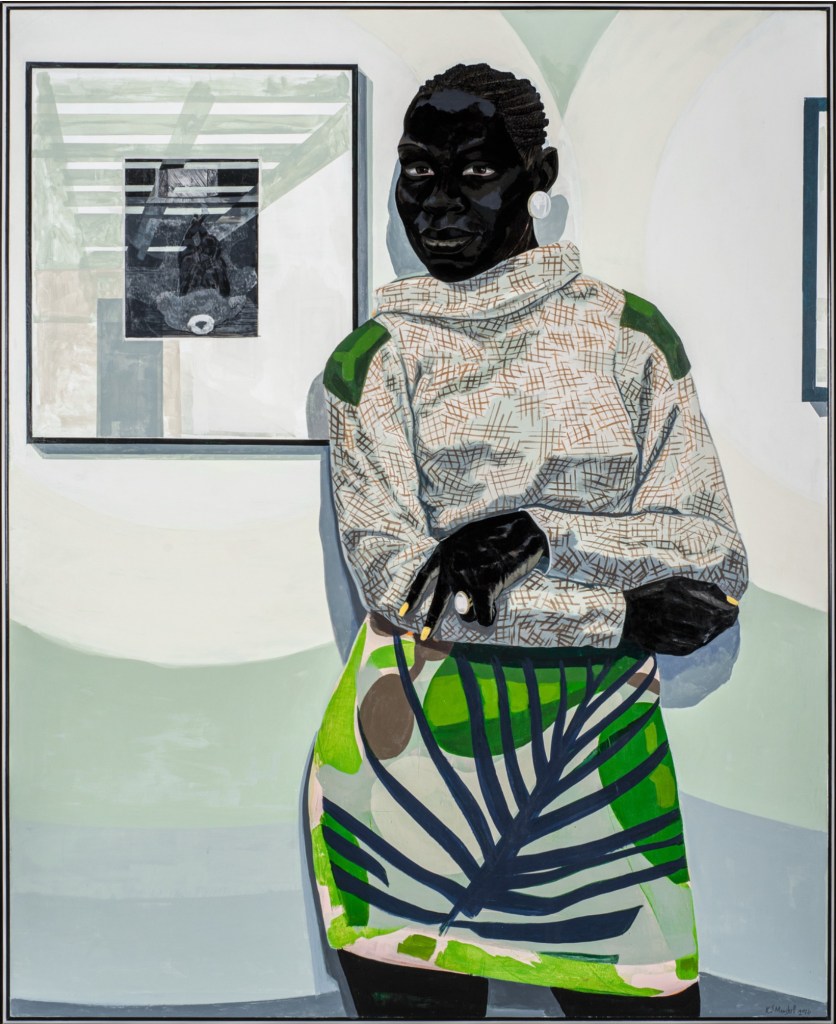

And I think that’s the broader point of both of these exhibits, that confronting imperialist and supremacist art is not about canceling traditional European art, but better understanding the context of that art and asking deeper questions about the gaps it leaves in our narrative. I have no doubt that Louise de Kerouaille’s portrait will go right back where it was in the Scaife Gallery when this exhibition closes, but exhibitions like Fault Lines teach us how to read the art we know better, and that has to be a worthy endeavor. When the Met takes Portrait of a Woman and an Enslaved Servant back, they don’t have to lock it in the basement, but its presence on display should have us asking about the presence of people of color in “museum art.” As the Guerrilla Girls asked about the presence of women artists in the Met’s collection (“Does a woman have to be naked to get her picture in the Met?”), we should be asking, “Does a Black person have to be a slave to get their picture in a museum?” Many modern museums have made strides toward greater diversity in both their artists and their art, but as the Carnegie International and these exhibitions show, the work is ongoing. But I think the goal is one worth pursuing.

[Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Gallery) (2016), in CMOA’s regular collection]

Leave a comment