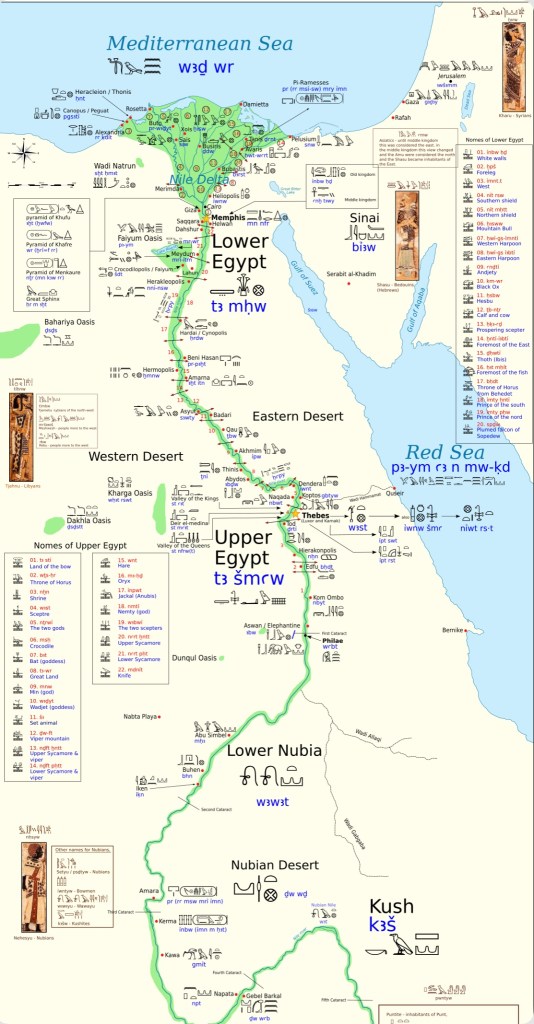

"We are leaving the Arsinoite now, afibi-t." She lifts her face to the breeze, her eyes closed. "What strategia does Memphis open to?"

"The Heptanomis," I reply, trying to coax a dragonfly onto my fingers. "And the last is the Thebais."

"Very good. What is the administrative division beneath the strategia?"

"The nomes, Aetia."

"And how many of them are there?"

I don't know, and seeing that her eyes are still closed, I cast a desperate look at Gaius who mouths the answer at me.

"Forty-two," I announce.

"Indeed. Forty-two cities that govern their lands for Alexandria, divided from the old days between the Red Land and the Black Land. Perhaps Gaius will tell us how many nomes are in each since he is being so helpful."

Gaius and I blush guiltily, and he says, "Twenty in Lower Egypt and twenty-two in Upper Egypt."

Children of Actium, chapter 33

I had half a mind to do an entry about my top ten favorite odd Egyptian hieroglyphs, but admittedly many of them there isn’t much to say beyond, “Check out this clearly ancient meme we no longer get!”

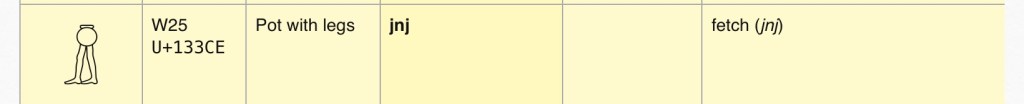

[Though some are fun on their own. I love that to express “get/fetch” (jnj) one adds legs to a pot. Hieroglyphs as a language have a reputation for obscurity, but a lot of it is actually very intuitive.]

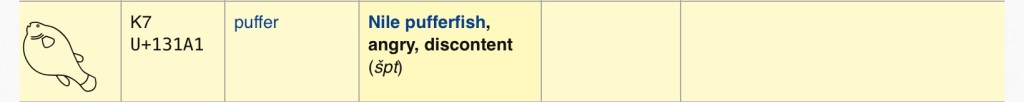

[Like how the hieroglyph of a Nile pufferfish (špt) is an ideogram for being angry (literally puffing up with rage until you look like the fish).]

What makes hieroglyphs, and many other logographic/lexigraphic languages, difficult to people coming from purely alphabetic languages, is that each glyph can be conveying either a singular morpheme/logograph, a singular syllable in a larger word, a specific item/animal/person, or a concept. The hieroglyph of a flamingo (dšr) is an example of this where the glyph could be referring simply to the bird, or to the color red. The interpretive part of reading hieroglyphs is attempting to arrive at the correct meaning through the context of the surrounding glyphs. This difficulty with Egyptian (as opposed to, say, Mandarin) is that the hieroglyphs represent a dead language with no modern speakers, so even assuming we are interpreting what we read correctly, because ancient Egyptian does not represent vowel sounds in its written script, any and all pronunciations are at best educated guesses based on how descendant languages like Coptic are spoken.

But what had really gotten me on this thought train is my favorite glyph in Gardiner’s Sign List:

[This one]

The first time I saw it out of context, I laughed because I pictured it as a pure ideogram. As in, “How often was the situation where a man throttling two giraffes coming up that the Egyptians needed to have this hieroglyph ready to go??” But as you can see in the expanded Wikipedia frames for this glyph, while I was actually correct to treat this as an ideogram, it is not the ideogram for an ancient sideshow act, but rather the ideogram representing the city of Cusae (Ksj/Kís in Middle Egyptian). And rather than talking about hieroglyphs, Cusae’s oddly specific glyph seemed like a good segue way into not just talking about it, but about Egypt’s sub-pharaonic bureaucratic government structures, which were so good at organizing an empire that covered nearly four thousand miles, that the empires that ultimately replaced it (Persia, Macedonia, Rome, and even Islam to an extent) rarely tinkered with local government upon their conquests.

[Cities and nomes often had very unique glyphs to differentiate themselves. As you can see, the ideogram glyph for Mahedj, the 16th nome of Upper Egypt is an oryx tending an irrigation system.]

With such a long, narrow empire that made distance always a consideration for a central authority in Egypt, chunking up the land into smaller subdivisions has been a part of Egyptian governance since practically the beginning. The three strategia mentioned in my CoA flavor text are relics largely of the late Ptolemaic period and the following Roman administration, where these bigger sub-structures with a sub-governor, the strategos, were put in place under the pharaoh or Roman praefect because their capital was so far north in Alexandria, far away from most of the empire/province. But beneath the king or praefect and the strategia was the original Egyptian municipal division, the nome.

Like so many “Egyptian” terms, nome is the Greek name for this local division, which in Egyptian was called sepat (sp3t). The Greek word nomós (νομός) originally referred to pasture or grazing land, but as the Greeks urbanized, its definition extended out to include the concepts of dwellings within a settled district, and while still in Greek vocabulary throughout the Hellenized world, the term would eventually be most readily applied specifically to the sub-districts within Greek Egypt.

But as the presence of a Middle Egyptian word for the same concept implies, nomes existed as administrative structures long, long before Alexander and his dudes showed up in Egypt. Specific nomes are attested to in the archaeological record as early as the reign of Djoser (c. 2600s BCE), but many historians suspect they could have come into existence simultaneously alongside the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt 1,500 years earlier. Beneath the pharaoh, Lower Egypt in the north and Upper Egypt in the south were the two largest subdivisions of the empire, and each was traditionally controlled from a capital city where the king, if able, would divide his time: most often through Egypt’s long history Memphis in Lower Egypt and Thebes in Upper Egypt. The nomes were the geographical division below the two halves of the empire (or beneath the three strategia later), and while the nomes would very occasionally change names over the millennia, their number remained surprisingly static, with forty nomes in Lower Egypt and forty-two in Upper Egypt, for a grand total of eighty-two local districts.

While the number of cities, towns, and villages within each nome varied wildly, each nome would have its own capital city beneath the larger royal capitals. And from the nome capital city, the district would be administered by its own local governor, the nomarch (Egyptian: h3ty’/hatya). As you can well imagine, most nomarchs were appointed by the king’s central government, either by sending a favored man to take up the position or presumably choosing a representative from a leading family already native to the district. The position had a tendency to become hereditary in a local or transplanted family, but one of the benefits of the nome system was that during the many periodic times of instability at Egypt’s monarchical level, the nomarchical structures could provide local stability even when the empire was in transition. There is even some evidence of nomes appointing new nomarchs and hereditary nomarchical lines when the central government wasn’t in a position to do so.

[Incidentally, later, the strategos of a strategia might also be the nomarch of a district. For example, the Heptanomis strategia began at the first nome (Inebu-hedj, “White Walls”) of Lower Egypt, whose nome capital was the city of Memphis (Men-Nefer in Egyptian), where the strategos was likely to base himself.]

Perhaps unlike a modern governor or mayor, a nomarch’s principal task, rather than implementing and enforcing laws, was to assess and maintain local revenues for the central pharaonic government. They would also be in charge of gathering corvée labor for the pharaoh, which more often than not would have been military conscription, but archaeologists have speculated that it may also have included large-scale public works projects and even the building of the pyramids. All of this makes nomarchs closer to medieval vassal lords than modern governors. We can also tell more about the nomarchs’ responsibilities based on other titles they held. “Hatya” is the common Egyptian name for a nomarch, additionally translated as “mayor” or “hereditary prince,” which is where we get a lot of our general framing of the position, but they were also described as Hery-tepaa (hry-tep’3)—“Great Overlord”—and Imi-r hemu-netjeru (ímí-r hmw-nțrw)—“Overseer of Priests” (The Complete Cities of Ancient Egypt, 62). The former is consistent with the type of government administration we’ve been talking about and are personally familiar with, but the latter might surprise you. But like in the other ancient civilizations like those in Mesopotamia, Egyptian legal and administrative structures were deeply integrated within the religious organization of the empire. Especially in remote towns and villages, priests doubled as doctors, judges, and government representatives, and were the closest many ordinary people came to an actual authority figure. However, by naming the nomarchs as the Overseers of Priests, the king could attempt (at least in theory) to have a person who could rein in the power of the priesthood and assert the central government’s authority over them.

[How historically successful the nomarchs were at this is clearly debatable, and depends entirely on how powerful the local priesthood was. The nomarch of Ta-Wer (t3-wr, “The Great Land”), the 8th nome of Upper Egypt, whose capital was Abydos, the main seat of Osiris’ cult, probably was more likely the Hem hemu-netjeru, the Slave of Priests, than their overseer.]

Now that we’ve laid some groundwork on the nomes and their leaders, let’s return to Cusae as an example for some specifics. Cusae was the capital city of Nedjfet-peht (nd ft pht), the 14th nome of Upper Egypt, located in the central Nile Valley roughly equidistant between Memphis and the eastern bend in the river where Dendera and Ombos are. The nome’s name means “Lower Sycamore and Viper,” to distinguish it from its southern neighbor Nedjfet-khentet, “Upper Sycamore and Viper.” Both of these nomes are relatively small, which might explain their paired names.

[Here in the nome chart from Wikipedia, you can see the two nomes’ hieroglyphs side by side.]

Like the oryx nome from before, the irrigation glyph topped by a heraldic standard is the base sign to signal that this is the name of a nome. Nedjfet-peht’s specific glyph markers are the horned viper in front of a sycamore on the left, with the glyph for the hindquarters of a lion over a loaf of bread on the right. The lion butt might feel weird, but it’s the ideogram for phety (phty), the Egyptian word for “strength.” Now, the loaf of bread could just be a loaf of bread as a sign of agriculture abundance, but the loaf glyph is also a uniliteral symbol for the “t” sound. But putting them together, you get phty-t, which is basically the second half of the nome’s name. This shows you how the phonetic sense of a hieroglyph can also work as a sort of visual pun, and why it’s so difficult to pin down a singular meaning for any glyph. This is doubly true when you take into account that Nedjfet-peht’s patron goddess was Hathor, likely in her form as the Lady of the Sycamore, an epithet connected to her chthonic role in Duat, where sycamores were associated with the giving of new life.

[Tomb fresco showing Hathor emerging with food for the dead from a sycamore. Because of their connection with the goddess of love, sycamores are also frequently a symbol of eternity for lovers, and couples often speak in surviving Egyptian poetry of rendezvous-ing under these trees to seek the blessing of Hathor. Though, to clarify, Egyptians are referring to the fig sycamore (Ficus sycomorus), not the big deciduous trees of northern Europe and the New World. Also, also: in a happy little coincidence, the day that I’m posting this (September 4th) marks the famous processional festival of Hathor of Dendera on the Egyptian calendar, Dendera being the goddess’ oldest cult center in Upper Egypt.]

Nedjfet-peht’s nomarch would administer the district from Cusae, which had some prominence during the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055-1650 BCE), based on the fairly sophisticated necropolis located outside the believed city site at nearby Meir. But otherwise, the most importance Cusae ever had during the dynastic era in Egypt was as the border point during the Second Intermediary Period between the foreign Hyksos 15th dynasty in the north and the Egyptian 16th and 17th dynasties based in the south at Thebes. Like as we saw with Ombos, Nedjfet-peht’s relevance as a small nome in Upper Egypt only continued its general irrelevance during the later Greek and Roman periods, though it would serve as the base city for the Legio II Flavia Constantia in the Roman province of Egypt from around 293 CE through the 5th century, though the capital of the Thebaid strategia administering the nomes in this part of Egypt would be at Antinoöpolis, the cult city Hadrian’s deified boy-toy, Antinous-Osiris. And as Ombos survives to today as Naqada, Cusae remains the small town of El Quseyya (القوصية; Coptic, ⲕⲱⲥ/Kos) in southern Egypt, where the past is never further away than a few dozen feet beneath the ground.

[Relief of Ukhhotep II, a hereditary nomarch of Nedjfet-peht during the 12th dynasty (1900s BCE), from his tomb at Meir. Frescoes from his tomb also show a lot of Hathor iconography, such as cows and bulls, and ritual scenes recognizable to the goddess’ cult. But archeologists have discovered tombs from Cusae’s elite at Meir from as far back as the 6th dynasty of the Old Kingdom (2300s BCE).]

So that’s a little about the nomarchical administrative structure of ancient and early modern Egypt, with some bonus hieroglyphic lessons thrown in for fun… but we never really answered the question of why giraffes for Cusae. And that’s in part because I have no strong answer. Why is the nome glyph for the 19th Upper Egypt nome two was-scepters and a foot? Why is the one for the 2nd Lower Egypt nome just a cow thigh? (Okay, that one’s because foreleg, ḫpš, also means “power.” Probably). Giraffes are not native to Egypt, and would have been coming to the Nile Valley from their frienemies to the south in Kush and Nubia. “Giraffe” on its own in hieroglyphs is memj (mmj), but as an ideogram could also be ser (sr), to foretell—perhaps based on a multicultural inclination across Africa to see giraffes as symbolically farsighted because they are literally farsighted due to their height.

And the hieroglyph of a man with both arms raised (without holding onto anything) is an ambiguous glyph that can either express joy (qaj) or mourning (haj). It might be a stretch, but I think it is possible to see Cusae’s hieroglyph as an encapsulation of the ultimate expression of Egyptian belief: that of ma’at, cosmic balance. Where the balanced person knows that foresight would only reveal joy and sorrow, likely in equal measure to please the gods, if not us. Just as light Hathor is both the love of this world and the endless Duat, and the other side of dark Sekhmet.

[And if it’s the alternate glyph for Cusae where the guy is holding two panther heads? I don’t know, probably means his parents went to Wakanda and all he got was this Black Panther jump rope🦒]

Leave a comment