I had promised more Daughter of Scorpions content, and I confess that I was briefly at a loss for topics we hadn’t already discussed during the other God’s Wife releases, until I realized we’ve never really specifically talked about something that is a major hinge in this story—mainly, the Roman imperial cult. So I thought today we’d take a look at the origins and evolution of this most peculiar of Roman political institutions and maybe tease out why it wasn’t quite as odd as it is often portrayed. And why it all wasn’t Julius Caesar’s fault…

[Perhaps with some help from one of its other founding members…]

As I mentioned in my entry about the evolution of magic in my God’s Wife series, it is often overlooked in ancient Roman studies that worship and deification of the dead was a practice that long predated the apotheosis of the newly minted Roman emperors. Familial cults to the di manes, the ancestral dead, had been a part of Latin religion basically for as long as we have records of their cultural practices. And like many other ancestral cults from around the world, Romans not only gave offerings at their manes’ shrines for the comfort of the dead, but with the expectation that they could assist their living relatives from beyond the grave. The most obvious sort of help would be toward the general, continued advancement of the family prestige, but requests could also be as specific as cursing rivals or defeating opponents in the courts or political arena. And there is a sort of basic logic toward one’s ancestors that people (mostly men) who were more powerful in life retained more power in death. Someone like Scipio Africanus (236- c.183 BCE), the great general and statesman who defeated Hannibal and the Carthaginians, was a more powerful manes mover than, say, an anonymous farmer known only to his immediate family. But Scipio is a good example of an early proto-public manes cult figure, as his imago—the mask made in a deceased person’s likeness that would be placed in a family’s home shrine—was in fact not in a house of one of his descendants, but was rather kept in the public Temple of Jupiter, where he gained a reputation as not only having ascended to the realm of the gods, but that he was in fact a son of Jupiter himself.

Some of this sort of cultural drift in the native manes cult was influenced by Rome’s increased contact with foreign religious practices, which we’ll get to in a minute, but despite their (deserved) reputation for cultural assimilation, some of this was homegrown as well. Despite the Roman Republic’s distaste for its dead monarchy, certain of its legendary kings, like Aeneas and Romulus, were still massaged into popular cult deities. The defied Aeneas was venerated as Jupiter (Pater) Indiges, and Romulus was subsumed into the multifaceted local god Quirinius, who we think was probably originally a Sabine god who was earlier absorbed into the Latin pantheon after their conquest of the Sabines. Both of these deifications were aided by a mythology that made both of these “historical” men demigods to begin with—Aeneas being the son of Venus-Aphrodite, and Romulus the son of Mars-Ares.

Though as my use of the Roman gods’ subsumed Greek equivalents suggests, the next leap in the manes cult’s evolution toward the imperial cult comes from Rome’s increased contact with the Greco-Hellenistic world. The Greeks themselves were somewhat late adopters to divine human cults, as their more historical view of death and the afterlife seems to have generally precluded even the sorts of direct aid that the Romans expected from their manes. Think of how contact with the dead in the Odyssey is even different from the Aeneid: Odysseus travels to the underworld on the advice of a goddess (Circe) to get the help of an exceptional mortal (Tiresias), and Odysseus initially pushes his own mother’s shade away from him because he wants to speak with Tiresias, who can supposedly help him rather than her. Meanwhile, Aeneas goes because his dead father (a manes), Anchises, tells him to and that he will help him when he arrives. Already the agency of the dead has changed cross-culturally.

Where the Greeks differed from the republican Romans is that they weren’t as adverse to honoring living men with god-like titles. Identifying men who’d performed extraordinary service to the polis with epithets like soter (“savior”) was fairly routine, and honoring a man’s daimon (roughly equivalent to the Roman concept of genius)—one’s divinely-inspired power bestowed on the soul by a higher deity—was frequent as well.

[Like, the playwright Sophocles was honored with the heroic denomination of Dexion for sheltering a cult image of the god Asclepius during the Peloponnesian War in this way.]

I know that this sounds very much like the Greeks were according divine honors to mortal men, but there’s a delicate semantic distinction here in degrees of veneration, and admittedly, the lines were sometimes blurry until the 4th century BCE. The simplistic summary is that early Greeks, like the early Romans, held all mortals on a level slightly below that of their established gods. Greek festivals to a man’s daimon were in practice not very dissimilar from the increasingly elaborate Roman triumphs being thrown for Latin generals. There were some largely unsuccessful attempts by various Greek tyrants to start personal divine cults for themselves, but the Greeks didn’t really get in on this sort of game themselves until Alexander the Great conquered the Egyptians in the 330s BCE and the Persians in the 320s—both empires already with established monarchical cults worshipping their pharaohs and shahs as god-kings. To cement his authority over both of these empires (and admittedly to stroke his own ego, too), Alexander quickly set himself up in these molds, and by 324, had issued proclamations to his Greek territories that he was to be worshipped as a god in theirs as well.

[The Greeks complied in the letter, but it would take a while for them to exult Alexander’s cult in spirit… and it would be long after he was dead.]

Alexander’s handling of public relations, especially in Egypt where he was worshiped as the son of Zeus-Amon, would set the tone for his successors, the Diadochi, but mainly the descendants of Seleucus Nicator, who ended up with Persia, and of course Ptolemy Soter in Egypt. But underneath these two larger dynasties were a whole constellation of smaller kingdoms and satrapies that also operated in this divine ruler milieu, and this would be largely how the Romans would come in contact with these practices. As Rome expanded its territories and influence across the Mediterranean, two factors began to converge. One was that Roman proconsular powers were increasing due to the growing distance between that official and home base, which made the older, more direct senatorial control of all decisions in the provinces and subservient territories impractical. The other was that this increased authority made the local populous more directly and independently “ruled” by that Roman representative, and therefore it became more common for, say, Athens to award said representative with the traditional Greek titles and honors we’ve been talking about if the Roman representative was thought to have performed an especially meritorious act for them. And, it shouldn’t be left implied: Roman territorial expansion also just exposed more Roman men with political influence to other forms of government, including those of divine monarchy. All of this, simply put, began to influence how Roman politicians viewed both the nature of power and the interplay between the mortal and the divine.

This is the complex stew that was bubbling on the 1st century BCE fire when Julius Caesar hit the scene. Popular history tends to treat Julius as if he just swaggered into the Senate on a whim and demanded to be worshipped as a god, but it’s closer to the truth that he was merely building on a well-established trend that had been moving in this direction for centuries. Naturally, like Alexander before him, he saw how living divinity influenced the Ptolemies’ ability to maintain control over a complicated empire like Egypt. But rather than seeing this solely as him wanting what Cleopatra had (though, obviously, that played a part), we could take the longer view that recent history had already seemingly demonstrated that the republican Roman Senate was not well positioned to directly control the territory it had amassed since its inception, as evidenced by how its solution had been to give individual proconsuls more power abroad than to reform itself. It may be revisionism to claim emphatically that the Roman Republic had to become imperial to rule what it had become, but there were serious administrative issues that the republican Senate appeared unwilling or unable to address to forestall that course. And in the manner consistent with the situation abroad, Julius had been previously honored throughout his career in the proto-cult manners of both late republican Rome and post-Hellenic Greece. He had been triumphed in Rome numerous times as a superlatively successful general, and Greek cities like Antioch had recognized his personal protection in the soter model.

Julius also had his personal familial situation that bolstered his elevation—again, arguably within established traditional culture. The Julii had always claimed their descent through Aeneas’ son, Iullus, which not only gave them divine blood ties to Aeneas-Pater Indiges and his mother, Venus, but to Romulus-Quirinius and his divine father, Mars, since the first king of Rome was also a descendant of Aeneas. Aside from this preexisting lore that placed the Julii manes far above most people’s, Julius’ uncle, Gaius Marius, had enjoyed an expanded non-familial manes cult among Roman citizens after his German victories, and after Sulla’s purges during the first Roman Civil War, Julius was one of the few remaining living Marian relations to enjoy the closest thing Rome had seen to such a popular cult since Scipio Africanus joined the Temple of Jupiter.

All of this is not to say that Julius should have necessarily pushed the Senate to official declare him a living deity (divus)—his stabbening suggests it was a bad idea—but the parts of the Senate that didn’t kill him had been happy to erect statues to him extolling his connection to his ancestral goddess, Venus, and award him a personal flamen (priest) in acknowledgment of this (it was Mark Antony). Sure, Cicero and Brutus were pissed on principle, but as I pointed out in my entry on the second Civil War, the average Roman seems to have been very on-board with these unusual honors for Caesar. And unlike the Greeks who had no trouble rioting against their “god” Alexander of Macedon the moment he was dead, the plebs of Rome nearly burned down the city trying to catch the men who’d killed their punitive god, Julius. Add the fortuitous comet that appeared over Rome after his assassination, the sidus Iulium, and it wasn’t too hard for Julius’ partisans to get him over the last symbolic hurdle. In 42 BCE, Octavius holds, with the explicit consent of the Senate, an official apotheosis for his dead great-uncle/adopted father, a ceremony to elevate the complicated human Gaius Julius Caesar to the godhood as the Divus Julius—the Divine Julius. And thus the Roman imperial cult was born.

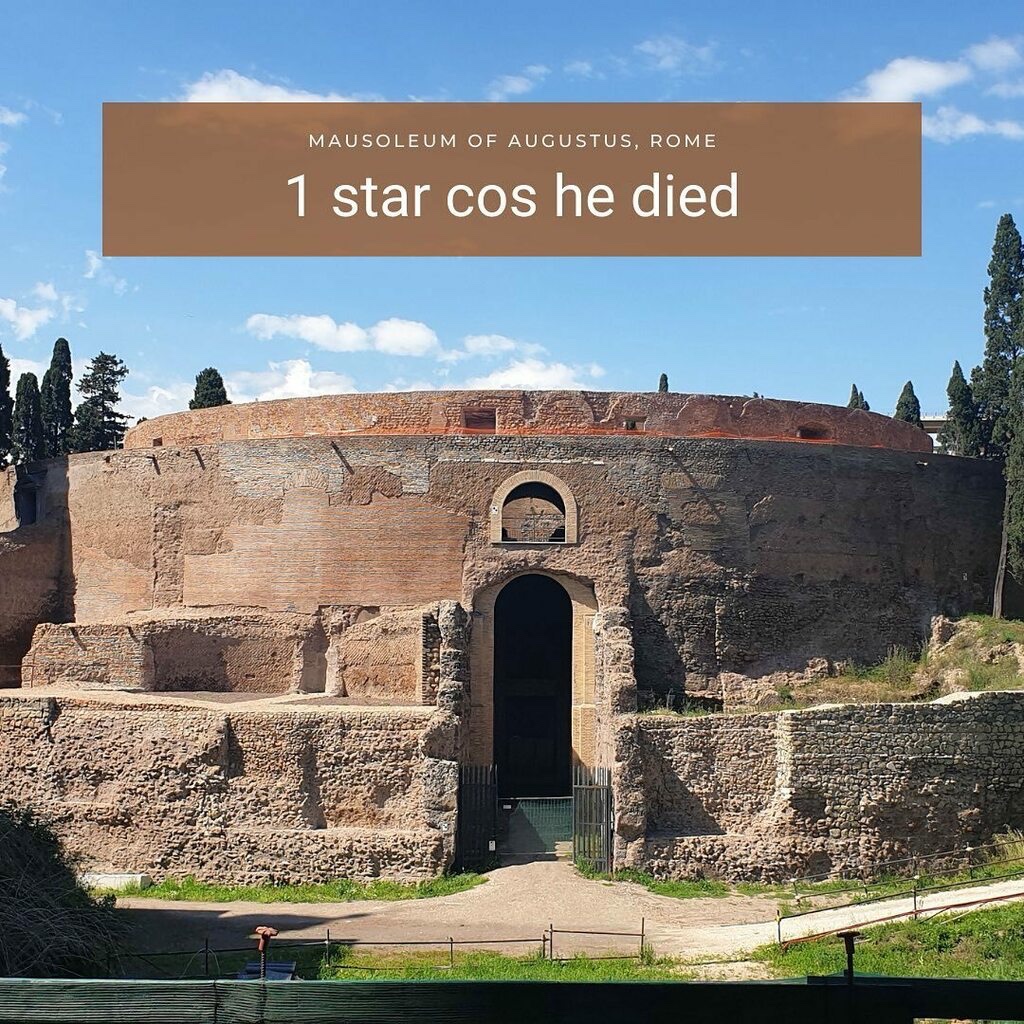

Well, sort of. You see, like any run of the mill divine cult, the imperial cult was only ever as powerful or noteworthy as the will to uphold it. A major point I try to make in my books is that divine power only exists in any meaningful sense so long as there are mortals willing to keep its memory alive, be it for the Egyptian gods or the deified Roman emperors. The Divus Julius perhaps became a god because of his (admittedly impressive) lifetime accomplishments, but he stayed a god because Octavius upheld his divinity. It was Octavius who went through the technical procedures with the Senate to get Julius’ apotheosis official sanction beyond anything Scipio or Marius had received. It was Octavius who made sure, at least initially, that Mark Antony’s post as Julius’ chief flamen was respected. And ultimately, it was Octavius’ personal identification with Julius as divi filius, son of the god, that would ensure that the imperial cult would continue beyond its founding deity. Because once that connection was made, it was easy for the Senate to choose to elevate him in exactly the same way upon his death, as the natural heir of the Divus Julius and the other Julian gods before them.

[While not accepting any of this as a fait d’accompli in Rome during his lifetime beyond identifying himself as the son of the Divus Julius, Octavius understood what Julius did about the realities of provincial administration outside of Italy and never fought too hard against having himself locally elevated in any manner that would ensure political stability in any given region. Here he is—wearing a combination of the khepresh war crown and what I believe is a variation on the Nubian-favored hemhem pharaonic crown—making an offering on a temple wall in Kalabsha in what was Egyptian Nubia at the time.]

After Octavius became the Divus Augustus, the imperial cult in Rome became an established entity, but the Senate did maintain some domestic control over its application. Octavius’ successor, Tiberius, was not a particular fan and resisted overtures from the Senate to apotheosize his mother, Livia, and that may have been one of many reasons no one championed his own elevation after his death. Caligula tried to force the issue by using the honoring of his god-bestowed genius/daimon to achieve living godhood, but the Senate never officially approved this. He did have his favorite sister, Julia Drusilla, apotheosized after her death, but Caligula’s own little-mourned demise meant that the Diva Drusilla’s cult effectively died with him, as future Romans had no interest in sustaining it. Claudius in turn used the long-desired apotheosis of his grandmother into the Diva Livia by the Senate to stabilize his control of the imperium after Caligula’s assassination and his unexpected elevation. Claudius’ own apotheosis was likely an even more cynical attempt by his adopted stepson Nero to consolidate power after Claudius’ murky death, judging by the meanly satiric Apocolocyntosis (divi) Claudii (The Pumpkinification of (the Divine) Claudius) that Nero’s tutor, Seneca the Younger, wrote about it.

After Nero’s death and the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, the imperial cult would continue in the same sporadic fashion until it was finally replaced by the supremacy of Christianity, but its complete eclipse took centuries. Smart emperors like Vespasian and Septimius Severus would use it to consolidate dynastic control, and even if the later emperors weren’t necessarily officially apotheosized upon their death, the genius of living emperors was usually sacrificed to across the empire, which sustained the trickle of lifeblood to the cult. Apotheosis usually happened whether the Senate technically agreed or not, but it still maintained input. A famous example of this was Hadrian’s deification of his lover Antinous after the latter’s untimely death in Egypt, which caused some debate in the Senate as Antinous wasn’t a member of the imperial family. The result of this was that Antinous’ cult would have ties to the imperial cult and would be present in many places throughout the empire, but Antinous wasn’t officially an imperial cult member.

[Hadrian was furious, but couldn’t force the Senate to change its mind.]

In its mature form, the imperial cult was perhaps less about the veneration of individual emperors and more a celebration of a singular religious thread that bound the disparate cultures of the Roman Empire together. In this, it was merely a continuation of the ancient civic religion of the Roman state that Latins had sacrificed to since time immemorial expanded to meet the needs of millions of people who hadn’t necessarily been born Roman citizens. The imperial cult anticipates the very cross-cultural religion that will replace it, for Christianity will spread across the Mediterranean in a very similar manner. Just as centuries of Hellenistic religious evolution set the stage for the next phase of Roman manes worship, the imperial cult, with its focus on the transitive nature of the mortal and divine, it in turn would ultimately prime an entire empire to accept the story of a god who became man, and a man apotheosized into a soter above all others. When approached from this perspective, the imperial cult becomes so much more than the cold and silly thing it is sometimes painted as, and one can see it for the revolutionary movement that it actually was.

Leave a comment