It’s been a busy couple of weeks on this end since my last post between travel for the Easter holiday and at last getting cover finalization for Daughter of Scorpions completed (paperback proofs are in the mail!), and this week I’m stuck in six hours of legal continuing education to maintain my attorney’s license. What this means for you all is that this week’s post is going to be factual, but perhaps a little lighter than some others. I thought that we’d take a look at the various kinds of horses in the medieval era—what they looked like, how they were used, and any other tidbits we encounter along the way. Because if you’ve spent any time reading about the Middle Ages, you might have wondered what the heck a palfrey is, and how it’s different from destrier or a jennet, or half a dozen other horsey beings. I’m hoping to clear some of that up for you, so saddle up, folks, and follow me!

Before we get too deep in the weeds with definitions, though, I should acknowledge that some of what we know about medieval horses and horse breeds is intelligent conjecture. Terminology and breeds shifted and evolved not only across time through the medieval period into the European Renaissance, but also across the various European principalities, as many of the terms used to describe horses were loan words from another language, such as French or Latin. As you’ll see as we go along, geography would also play a significant role in this, as what a “destrier” looked like in medieval Palestine was potentially extremely different than what a horse labeled that would like in England or the Dutch Low Countries. And we must always contend with the fact that many of our sources from this time are fictional chansons and stories written by monks and poets who might not have necessarily been up on the nuances of contemporary equestrian semantics. That said, we can make some broad generalizations.

The medieval horse nonpareil was the destrier, the premier warhorse of the era. A good destrier was built to be strong enough to carry a fully-equipped knight into battle, yet dexterous enough to navigate a chaotic medieval battlefield or tournament melee, as well as the one-on-one jousting arena. They also had to be temperamentally able to be calm enough to control in battle, but courageous enough to bite or kick enemy attackers on command. Indeed, the word destrier is an Old French cognate of the Latin dextrarius or dextra, both referring to the right hand, which itself may be reference to either the horse’s right-leading gait or where it was led beside a knight before battle.

This leading beside a knight was due to the fact that destriers were rarely ridden except right before a battle, both to conserve their strength and because of their exorbitant value. A destrier was likely the most expensive thing a medieval knight owned—a well-bred one typically costing at least a thousand marks, a fabulous amount of money for many of the lower nobility who filled the equestrian ranks of most armies. This is in part why the biggest prize to be earned in defeating an opponent in a tournament was their horse, something that could grant a lower-ranked knight instant higher status. This is how William Marshall moved up the ranks of the English nobility in the 12th century, as winning opposing horses and armor not only let him upgrade his personal equipment like he was leveling up in a video game, but also gave him valuable assets to either sell or give as gifts to build loyalty among his retainers.

Like all the medieval horse terms we’ll talk about, “destrier” was a descriptor, not a specific breed, and as I mentioned earlier, what was considered a destrier-worthy horse might depend where in the world you were, and when. In Italy in the 15th century, where wide, heavy plate armor had overtaken the chain mail hauberks of previous centuries—as you can see in Paolo Uccello’s The Battle of San Romano below—destriers would be, pretty much by necessity, enormous horses. The modern French Percheron is likely the descendent of this type of destrier, with the Belgian/Brabant, and the English Shire and Suffolk Punch making up the other oldest draft horses that fit this type.

[The Battle of San Romano (detail) (1435-60)]

[Percheron]

[Suffolk Punch]

But even in The Battle of San Romano, we see other, lighter destrier types that were popular throughout the pre-modern era.

[Alternate panel in The Battle of San Romano]

These horses are still muscular, but noticeably lighter in frame, and look more comfortable rearing up and holding a striking position. These horses are likely either Spanish-bred hybrid breeds like the Andalusian, the Lusitano, or their descendant, the Lippizaners of Austria; or they are one of the lighter northern, proto-warmblood breeds like the Frisian.

[Andalusian]

[Lippizaner]

[And the best, most beautiful horse humanity has ever created, the Frisian😍]

But what are the Spanish horses a hybrid of, you might be asking? The answer is largely an infusion of Arabian and North African Barb horses that came into Spain with the Muslim medieval invasions. These horses are where the thicker native Spanish horses get their sometimes-dished profiles and exaggeratedly arched necks. However, these eastern hybrid destriers were not limited to the Iberian Peninsula. Horses are challenging to transport in the modern day, so imagine how much more difficult it was to get European horses to survive months on the road or in a ship to get them to Latin Palestine and the crusader states. These difficulties, combined with the same martial contact that Spain had, led to most medieval depictions of Crusader destriers being much lighter, eastern looking horses.

[Arabian]

[Barb]

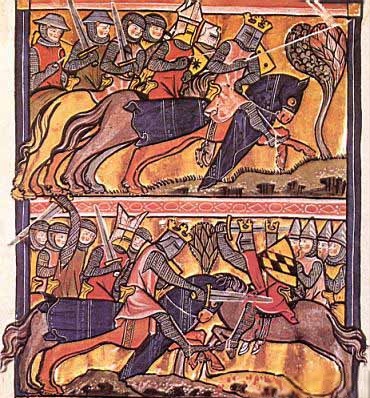

Arabs or Barbs pack a lot of strength for their relatively modest size, and require a heck of a lot less forage than your average draft horse. They also had the added advantage of being specifically bred to be adaptable to the hot climate of the Middle East, as most other horse breeds are extremely susceptible to heat. Being Arab crosses, you can see in medieval illuminations that these eastern destriers were probably much smaller in size than the draft-bent European destrier, as eastern knights’ legs and feet tend to extend well past their horses’ barrel (torso). Horses are measured in hands, which are counted from the ground to their withers (shoulder), and the typical Arabian horse is usually 13-15 hands tall, while a typical Belgian can be 18 hands or taller, with most “basic” horses like Thoroughbreds falling somewhere in the middle. This situation was compounded by medieval knights riding in a position with their legs extended in their stirrups (when they got them in the ~8th century), “western style,” rather than in the shortened stirrup position of most international “English” riding. This is one of many reasons they wore long spurs, so their feet could stay in contact with their horses to give them directions.

[Note how much lighter these destriers are built, and how far down their riders’ feet dangle past the horses’ barrel.]

But what if you were a knight who couldn’t afford a destrier? The other main medieval warhorse was the courser. A courser was generally a lighter, quicker, horse than a destrier, but as even knights who owned a destrier would typically ride a courser through a march or on non-battle business, a good courser had to also be strong enough to carry its master in full armor. This versatility, combined with its much more reasonable price, meant that in real medieval battlefields, many—if not most— knights would have been mounted on coursers rather than destriers.

[This knight attempting to steal a tiger cub by distracting its mother with a mirror (classic bestiary lore) is riding a horse that would probably be classified as a courser.]

Coursers, whose name comes from the Old French cours (to run), were also the all-around horses of the male nobility, used for hunting, hawking, and general travel. As a result, while a courser could be built like some of the lighter destriers, many of the modern descendants of these horses are older carriage and sporting breeds. British horses like the Irish Sport Horse, Hackneys, and Cleveland Bays are good examples of this sort of powerful, in-between type of horse, as well as continental breeds like the Dutch Warmblood or Trakehner. Essentially, if you’ve seen a dressage competition, which began as military exercises, the horses most built for those are prime courser material.

[Irish Sport Horse]

[Cleveland Bay]

[Dutch Warmblood]

[Trakehner]

Knights, though, weren’t the only people on a medieval battlefield that required horses. They had a whole entourage of squires, men-at-arms, and other personal who needed to move with a mounted master, and if a medieval equestrian was too poor or too low in rank to merit a destrier or courser, they rode a horse called a rouncey. “Rouncey” comes from the Latin runcinus (rough), and they could be just about any type of all-around horse. They might be lower-end coursers, or they might even be less exalted breeds of draft horses pressed into military service as required. This latter impression comes from earlier medieval texts that refer to a runcinus as a “harrowing” (plowing) animal. Therefore, even more than generalized terms like courser and destrier, when a source calls a horse a “rouncey,” one is likely meant to picture a horse of greater age or lesser quality.

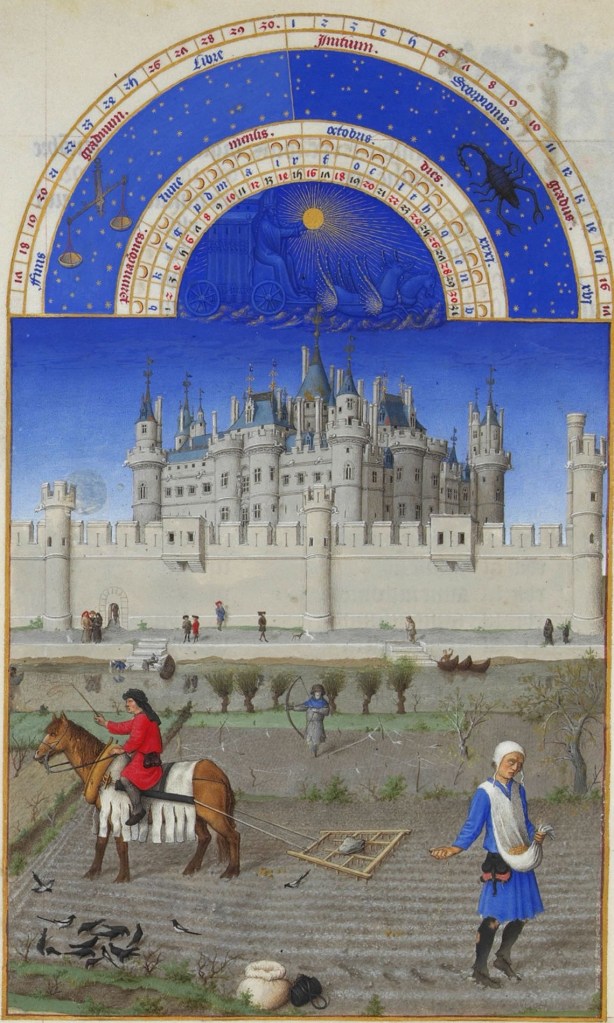

[Here in the October illustration in Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, you can see a horse harrowing in front of a castle. Such an animal would likely be considered a rouncey.]

If a horse was smaller than 14 hands, they might still have useful pack or hauling capabilities. These were sumpters, that could be used for plowing, mercantile carrying, or hauling fuel or timber. Many modern working ponies like Welsh ponies or the small Icelandic horse are good examples of sumpter-style horses. In the case of the latter in particular, which is strong enough to carry grown adults, you can see how horses might blur the lines between the types, and what a horse might be considered might come down to how that particular animal was used. If a sumpter-sized horse was able to carry a grown man and do so with some speed, they could be used by light cavalry or archers, in which they were called hobbies, which is where we get the term “hobby horse” from.

[Welsh Pony]

[Icelandic Horse]

The Icelandic Horse, with its distinctive tölt gait, is actually a good segue way into our next type, the aforementioned palfrey (or jennet, if it was Spanish-bred). Up until now, we’ve pretty much been exclusively speaking about male riders, but palfreys were more often than not the horse of choice for women and non-military riders like the clergy. This was because what typically made a palfrey, as opposed to a courser, was its pleasing gaits. Most horses have at least four standard gaits: walk, trot, canter, and gallop. So-called “gaited” horses, however, have one or more extra gaits that usually create a smoother gait between the trot and the canter, one that is perhaps closer to the speed of the canter without increasing the jolting motion of a fast trot in the bargain. Several Spanish breeds, like the Peruvian Paso and the Paso Fino achieve this by having the horse naturally swing its front legs out to the side as it propels itself forward at the trot, which creates a sort of floating, dance-like motion and lessens the impact of the trot.

[A Peruvian Paso mare, with her foal already showing the breed’s distinctive gait. Gaited horses get their special gaits genetically, though they can be enhanced by training. In the last twenty years, geneticists have isolated a mutation in these horses’ DMTR3 gene that gives them these abilities—and this mutation likely traces to a single genetic ancestor for all gaited horses.]

The benefits of gaited horses like palfreys are twofold. They were usually smaller and less-aggressively trained than the warhorses, making them more suitable to a more generalized rider. Also, their specialized gaits made them able to travel faster over longer distances with more comfort to their rider. The trot is the most efficient horse gait for long distance travel, but even with the (much later) inventions of posting—the rider raising themselves up in the stirrups on the beat of their horse’s steps—and the forward-seat saddle, it is the least comfortable gait for the rider. Gaited and ambling horses’ special gaits often give them gentle, skimming trots or run-walks that ameliorate that to at least some degree. This is why the United States has developed so many different gaited horse breeds—pioneers and explores of the western United States needed horses on which they could cover huge distances over uneven terrain in as much comfort as possible.

[The Tennessee Walker/Walking Horse is a particularly popular gaited American horse, with its ambling run-walk that one can sit through without posting.]

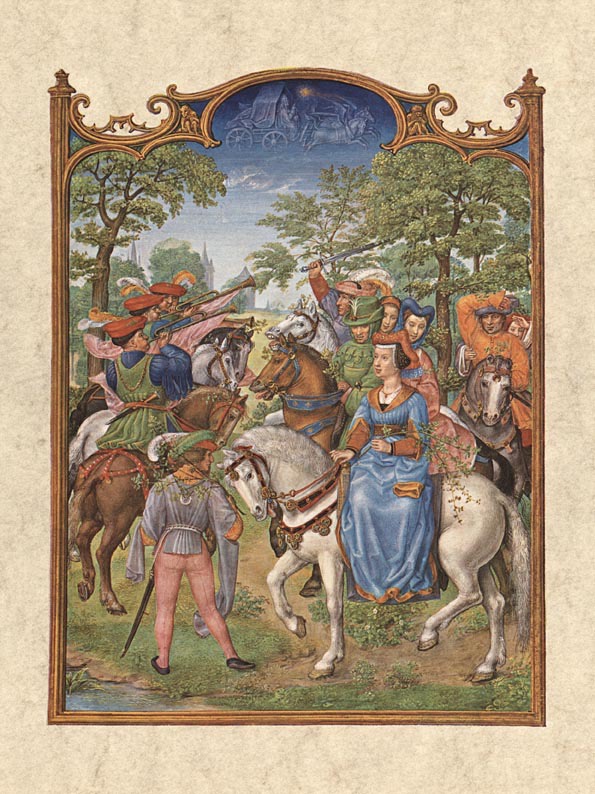

[Like the arched necks of the Spanish destriers, many palfreys were also bred to be visually pleasing, with elegant profiles and fancy, high-action steps.]

[The American Saddlebred (here) and its cousin, the Racking Horse, are modern horses with this high step. Unlike the specialized gaits, these horses’ genes give them the musculature to achieve this impressive action, but they must be typically trained to perform it. Like so many horse sports, teaching horses to perform the rack is controversial, as it often involves forcing the horses to wear restrictive matrices on their legs and weighted shoes on their hooves to train their motions to the exaggerated lift expected in the show ring.]

[Despite what you might imagine, medieval women rarely rode in sidesaddles, of which we have very little record of in Europe before the 14th century, and wouldn’t achieve anywhere near a consistent design before the 16th century. Here, we see a 16th century illumination of Anne of Bohemia (1366-1394), who is credited with creating this earlier, full sideways iteration of sidesaddle riding.]

To wrap things up, these weren’t the only types of medieval horses, but they were the most commonly mentioned in our sources. What really comes through in the totality of horses in this period is their versatility. Aside from the ultra-specialized destrier, many medieval horses had to fill a variety of roles in their owners’ lives, moving seamlessly from the fields, to the hunt, to war. They had to be strong, but also fast and comfortable in a world that relied on them as a primary source of transportation. Additionally, they were a source of income, as well as a sign of wealth and taste. Academics may still argue about their sizes or appearance, but their worth is beyond debate🐴

Leave a reply to sopantooth Cancel reply