“…our virtues and our vices depend too much on our circum-stances…” (Fanny Hill, p. 77)

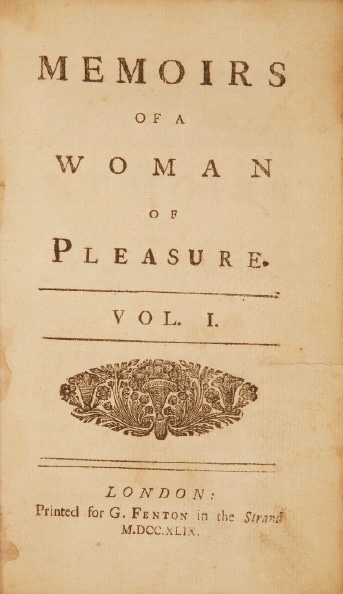

I recently read John Cleland’s infamous novel Fanny Hill: or, the Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (1748/9), and while not really a piece of high literature, it got me thinking about a whole host of other banned/censored books and attendant issues like legal obscenity, women’s fiction, and what really constitutes a “dirty book”—and I wanted to kind of free associate about it with you all. At this point in my literary life, I’m a pretty middle of the road reader in this arena. I’m not a habitual reader of romance or erotica as a genre, but I’m not against sexual content in books on principle or anything. I’m generally not seeking out explicit novels, but I’m not going to fling them across the room in Puritan horror if they cross my path—part of the reason I feel like I can be a good moderator in this discussion. Who knows? We might end up somewhere deep, or at least interesting.

When you’ve completed an English Literature degree and can on average hit well over a hundred read books a year, you get to a point where you’ve worked through most of big hitters in the literary canon, and you start to work your way down into the secondary and tertiary levels of “classic literature.” I’ve also read a lot of books in the literary canon that have salacious reputations, though I’ve found—as I’m sure some of you have, too—the salaciousness of many of these books is pretty overblown, even by the standards of less permissive times than our own.

I think some of the confusion modern readers might have toward historically infamous novels is because up through the 1960s, calling a book “obscene” really in involved two different objections to the books’ material: sometimes it meant that a book had explicit sexual content; and sometimes it meant that it implied sexual behaviors that were offensive to the status quo elite, and what could be construed as their sense of social or political morality. As a result, as a modern reader coming to old books infamous for the cultural or legal stir their publication generated, you tend to have a wide spectrum of experiences as to how shocking those books might actually be to you in terms of content.

I think there are roughly three categories for these books: the first I’d call “Pillow Book novels,” that is, books that specifically offended the sensibilities of the Victorians and Edwardians, and therefore developed scandalous reputations based on implied socio-cultural differences. Sei Shōnagon’s court diary is mostly a literary burn book full of listicles of stuff she hates and put-down poems she wrote to entertain a medieval empress of Japan, but it developed a reputation when it was translated into English in the 19th century because it was (understandably) blasé about mentioning aspects of Heian Japanese culture that were alien and subversive to contemporary English people—mainly the polygamous, uxorilocal (husband and wives living separately, with marital relations and child rearing centered in the wife’s family) nature of Japanese marriage at this time, with a comparatively (within certain parameters) lax attitude toward extramarital relations for women. For example, Shōnagon talks about spending the night with men she’s not married to, but The Pillow Book doesn’t go into explicit detail about the sex she presumably has during that night. Just implying it was enough to scandalize her first readers in English, but that’s probably not considered truly “dirty” by most of you today.

A sort of corollary to this one would be D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover (1928), which has a huge erotic reputation and was the subject of several publisher bans and obscenity trials in multiple countries up through the 1960s. But if you read it, one gets the impression that, at least initially, what a lot of people were really objecting to was the idea that a “lady” might find a lower class man sexually attractive and cuckold her poor, titled husband. This is I think why Constance (I see what you did there, Dave…) Chatterley gets more grief than say, Emma Bovary or Anna Karenina, who while condemned for their adultery, at least have the decency to stick to lovers of their general social class. Anyway, it’s been a while since I’ve read it, but I don’t recall clutching my pearls much at LCL. Kind of the same for Fanny Hill’s rough contemporary Moll Flanders (1722), where the criticism is for situational disapproval, rather than Daniel Defoe writing mass market pornography. Moll is a thief and conwoman who through a series of convoluted events ends up briefly (unknowingly) married to her own half-brother, among other crimes, which is against social norms, but again, is not laid out in pornographic detail. That was another one I read in college after being told it was really dirty, and was more often bored than titillated by.

The second category of so-called obscene books I’d label “Tropic of Cancer novels.” Henry Miller’s pre-counterculture 1934 novel is, unlike Chatterley or The Pillow Book, very sexually explicit, but in a way that also feels extremely performative. You might disagree, but to me, Miller, and later counterculture writers like William S. Burroughs and Norman Mailer, write their sex scenes and swearing with the air of naughty teenagers trying to get a rise out of their teacher from the back of the class. While certainly subversive at the time of their initial publication, I personally find that this type of writing, as a result, ages really poorly as the culture shifts behind it. I was still relatively young and naïve when I read ToC, and I mostly alternated between sort of queasy and mildly bored through its more explicit parts (i.e., “Urgh…” and “Yeah, yeah, I have one of those, Henry; it’s not that shocking…yeah, I have those, too. Big whoop”). I’m sure some people might beg to differ, but if I’m going to read graphic sex in a book, I’m not really looking forward to scenes that are designed to be gleefully lurid and degrading to all involved. Maybe it’s because, much as Moll Flanders well predating the Victorio-Edwardian scandals of Lady Chatterley, writers like Miller and Burroughs seem to think of themselves as ahead of their times, while not even hitting the depraved heights of another Defoe/Cleland near-contemporary, the notorious Marquis de Sade (1740-1814) and his army of snuff-smut novels.

Finally, there’s the third category, what I’d label—to return to Asian literature—“Plum in the Golden Vase books,” which are novels that are truly old enough to be canonical literature (pre-20th century), and in spite of their age, are also truly explicit in their content in a way never really intended by other maligned canon writers like Lawrence, Defoe, and James Joyce. The aforementioned de Sade definitely fits this category, though the depravity of his novels also triangulates on what many modern readers would deem quainter crimes like blasphemously excreting bodily fluids on a crucifix, which, for better or worse depending on your inclinations, might just as well be happening at your local public art museum. The Plum in the Golden Vase (Jin Ping Mei 金瓶梅) is a 17th century Chinese novel mostly about the sexual adventures of Ximen Qing and his wives and concubines, three of whose names (Pan Jinlian, Li Ping’er, and Pang Chunmei) are referenced in the title, which of course is also a sexual innuendo (it’s an insertion joke).

[Many people have argued that Fanny Hill’s title is also meant to be innuendo (female genitalia joke). However, there is no record of “fanny” as a slang for female genitalia before the 1830s, so it seems much more likely that the innuendo was the result of the book rather than the other way around. (This is one of the few Jin Ping Mei illustrations I could find that was PG. You’re welcome (or not!))]

And while someone has helpfully calculated that sex scenes take up only about three percent of Jin Ping Mei’s gargantuan 3,600 page count (in English), do keep in mind that what that actually amounts to is around seventy-two separate graphic sex scenes in one of the so-called Six Classic Chinese Novels. Anyway, after being told it was explicit, I was actually surprised at how explicit it was.

This is where I’d situate Fanny Hill. I knew it had a dirty reputation, but it comes up periodically on English Lit lists and I kind of expected a Moll Flanders experience (an “Ooooh! She’s not quite a lady, is she?” sort of thing). But oh no, dear readers, to quote a reviewer on Goodreads, “Okay, firstly, this is porn. Just porn.” And like that woman, I’m not even saying that judgmentally, I’m just stating a fact. I wasn’t super familiar with the novel’s history or that of its author outside of later legal obscenity cases, but in all of the multiple versions that John Cleland (1709-1789) told about the novel’s inception, he sets out explicitly to write an erotic novel. The closer to true version is that Cleland, imprisoned for debts in Fleet Prison, wrote Fanny Hill as a means to get of jail on his own, or at the behest of a publisher looking specifically for a smutty novel.

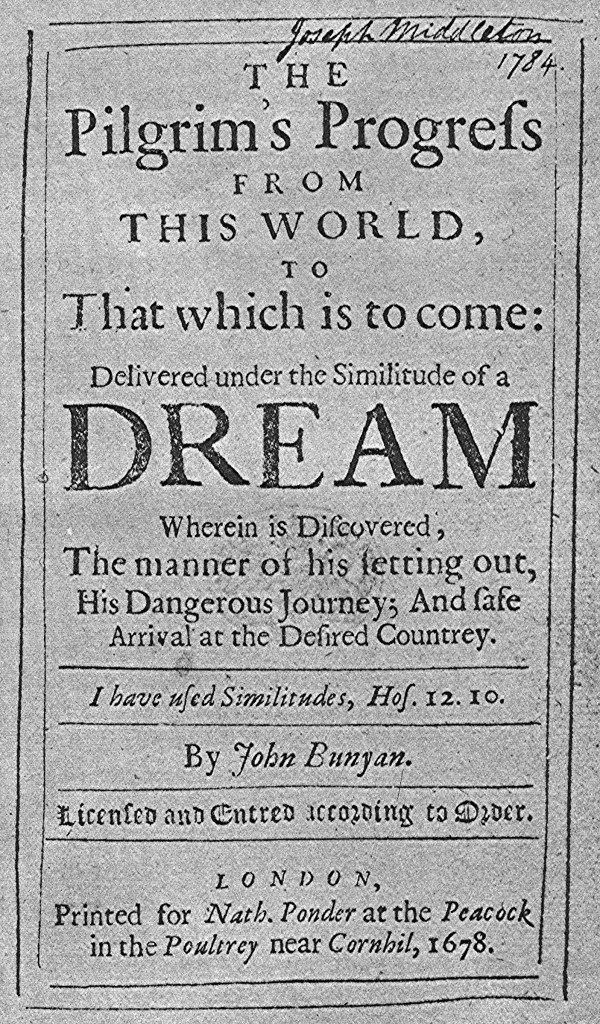

[Look, when you’re in jail, some people write interminable, overwrought allegories about God, and some people just want to write Baroque Wattpad erotica…]

And actually, comparing Fanny Hill to Wattpad or AO3 fanfiction isn’t entirely off base. Because it can be argued that, like all of the “real” dirty novels we’ve been talking about, Fanny Hill is a sort of fanfic. The Plum in the Golden Vase is an obsessive, rambling, sexy fanfiction of the much more respectable Water Margin/Outlaws of the Marsh by someone who read about Wu Song killing his murderous, sexually promiscuous sister-in-law, Pan Jinlian, and clearly went, “Wait—can we go back and hear more about the slutty sister-in-law??” Fanny Hill, like a few of de Sade’s novels, are directly engaging with the most popular romance novel of the 18th century, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela: or, Virtue Rewarded (1740). Like Pamela, Fanny Hill is an epistolary novel about a naïve fifteen year old middle/lower class girl and the adventures that ultimately lead her to a virtuous, love-match marriage. Admittedly though, that’s kind of where the similarities diverge.

As I was getting into Fanny (yikes, questionable choice of words there…😬), my first reaction beyond the already mentioned surprise at its content, was, “Oh! This is asking the question, ‘But what if Pamela Andrews had been a slut?’” And unlike Richardson, who on the frontispiece of Pamela had claimed that he wrote the novel, “In order to cultivate the Principles of VIRTUE and RELIGION in the Minds of the YOUTH of BOTH SEXES,” neither Cleland nor I are necessarily against a slutty Pamela. Richardson has Pamela virtuously resist the rakish Mr. B until she can turn her rake into a prince (and spawn a legion of romance imitators down to the present day), but Cleland wonders if you can still get to the virtuous happily ever after while having some raunchy fun along the way.

Unlike Pamela, who at the start of her story is respectably placed into household service at Mr. B’s, Fanny is orphaned and left to make her way on her own, and falls into the hands of a procuress in London. This is not the first brothel she ends up working in, but she loses her virginity to Charles, a young man with whom she falls mutually in love with. They are separated by circumstance, which frees Fanny up for more sexual adventures in the meantime, but most of which happen to her by her own consent as she moves from high-status prostitution to kept mistress. While deploying every 18th century euphemism for genitalia you can imagine, Fanny engages in voyeurism, orgies, BDSM, and lots and lots of good ol’ penetrative sex. And while she believes in the superiority of the love-driven intercourse she enjoyed with Charles, she’s not a helpless victim of sex trafficking or anything, and she is portrayed as overall enjoying her brief career as a sex worker. After she is living independently on the inheritance left her by a rich client at the ripe old age of nineteen, she runs into her lost first love, Charles, now destitute himself, but still wildly in love with her. He accepts her sordid past (although she was still a virgin, he did first meet her in a brothel, so it’s not like he wasn’t aware of her situation), and the two marry, have some kids, and live as happily ever after as Pam and her Mr. B.

And although the older Fanny looking back on her progress in these letters to an anonymous lady friend remains very sex-positive for the 18th century, she too ends her letters with the Richardsonian claim that she really wrote this pornographic memoir as a way to educate the youths in virtue:

“Thus, at length, I got snug into port, where, in the bosom of virtue, I gathered the only uncorrupt sweets: where, looking back on the course of vice I had run, and comparing its infamous blandishments with the infinitely superior joys of innocence, I could not help pitying, even in point of taste, those who, immersed in gross sensuality, are insensible to the so delicate charms of VIRTUE, than which even PLEASURE has not a greater friend, nor VICE a greater enemy. Thus temperance makes men lords over those pleasures that intemperance enslaves them to: the one, parent of health, vigour fertility cheer-fulness, and every other desirable good of life; the other, of dis-eases, debility, barrenness, self-loathing, with only every evil incident to human nature.” (Fanny Hill, p.223)

Whether you find this satirical lamp-shading by Cleland is, of course, apparently a question for the courts.

As you can imagine, the legal systems that were scandalized by Constance Chatterley was not amused by Fanny Hill. Within a year of its initial publication, Cleland was disavowing it before the King’s Bench to avoid being thrown back into prison, this time on the charge of “corrupting the King’s subjects.” The novel would enter underground, pirated status until the 1960s, when British bookshops began circulating uncensored copies of it on the strength of the legal gains made by Lady Chatterley (in R v Penguin Books Ltd (1960)). The books were still seized, and although a few book sellers tried to challenge this, Fanny Hill wouldn’t be openly available in the UK without pushback until the next decade.

In the US, the novel would be challenged all the way up to the Supreme Court, where Memoirs v. Massachusetts (1966) would be used to clarify the earlier Chatterley-adjacent ruling (Roth v. United States, 1957). Roth established the standard that needed to be met to deem a work obscene, which was 1) the work appealed to “prurient” interests, 2) its content was “patently offensive,” and 3) the work had “no redeeming social value.” Because censors looking to ban a work had to meet all of these criteria, the Earl Warren-led Court was seen by many conservatives to be probably much more pro-pornography than it actually was.

[Well, except for Justice Douglas. He was definitely pro-pornography…]

In its ruling, the Court, in a plurality decision, ruled that while Fanny Hill met the first two Roth criteria, the state of Massachusetts couldn’t show that it had no societal value (the plaintiff likely leaning on arguments used in the UK that the book was sex-positive and bawdy, rather than legally pornographic). This is where Fanny’s venerable age probably aided its case—it’s hard to get up in arms about “pornography” that the Founding Fathers could read.

[You know Ben Franklin was reading Fanny Hill…]

The Court did hedge a little by saying that if the book was marketed solely on its prurient appeal that it might be subject to obscenity laws, and subsequent Court decisions have largely reverted to a broad “community standards” stance on whether or not Fanny Hill and books like it are censorable. Which in layman’s terms basically means that you can probably find Fanny Hill in a blue state bookstore with little difficulty, but you might have to get it shipped to your house in a red state. Though all of that is largely academic, as Fanny Hill is public domain and freely available all over the internet (I got my copy on Project Gutenberg).

[Project Gutenberg: Smut Merchant??]

So after all that, you’re probably wondering what I actually thought of the book. Well, to start off with, I agree with the Court plurality’s ruling that Fanny Hill doesn’t meet the Roth standard for obscenity, and that it does have “redeeming social value.” Granted, I also believe that pornography has social value (within reason), but in the barely-there plot between the hardcore erotica, Cleland occasionally has some interesting things to say about sex, society, and the place of women in both. It’s by no means a feminist novel—and it likely hasn’t escaped many of you that most of these “salacious” books about women are by men—but Cleland writes Fanny as character with a surprising amount of heart and innocence that she maintains throughout the story. At no point is she brought to any kind of lasting degradation or comeuppance for leading a sexual life. Her madams treat her well and her fellow prostitutes are convivial and helpful to one another, and they receive happy endings as well, whether returning home to families or marrying lovers/clients.

However, as progressive as it is on female sexuality for its times, it’s still a book from the 1740s, its views on the less vanilla sexual practices it talks about, particularly in the second half when Cleland runs out of novel ways to depict heterosexual intercourse, are less clear and often less laudable. As is so often the case with male writers, lesbian experiences are treated more favorably than sex between men, and while consent is an important aspect of the one true BDSM tableau, one of Fanny’s friends also seduces a mentally handicapped boy not capable of consent. Like all books centered on sexual fantasy, your willingness to engage with these, or any of the more straightforward erotica, will definitely vary. The lens through which you view the story will also change how you engage with it: is this a stimulating piece of erotica? A cheeky satire of female conduct novels like Pamela? Just a bar bet that Cleland couldn’t create a story about a prostitute without resorting to “vulgar language”? Three pornos in a trench coat of a novel? At the end of the day, Fanny Hill is one of those books that mostly ends up being a reflection of what you as an individual reader bring to it.

As I said earlier, as a not especially enthusiastic consumer of romance/erotic fiction, it’s hard for me to love a book whose tissue-thin plot mainly serves as a way to move from one sex scene to the other, but just because I didn’t love it doesn’t necessarily mean that I hated it, either. It’s a short, quick read from a literary era that tends to be more wordy and ponderous, and it’s certainly not boring. Mostly I came away from the experience appreciating it as an interesting glimpse into an off-the-beaten path part of English literature, and its varied history with other books and the law were worth delving into in their own right. It’s also good to be reminded that these kinds of books have always been around in every culture, and that the pre-Fall time where people weren’t writing smutty fanfics about sexy, pure-hearted prostitutes is even less realistic than the sequential orgy that happens in Fanny Hill 💋

Leave a comment