This week, I thought we’d take a look at one of the most interesting cultural artifacts to come out of the medieval period: the medieval bestiary. Although present throughout the Middle Ages and all over Europe, these elaborately illuminated animal catalogues were most popular during what is now often referred to by modern historians as the 12th century Renaissance and most common in France and England. On the surface, these manuscripts might appear to be little more than beautiful, but wildly inaccurate, interpretations of the animal kingdom by a credulous European audience.

[And to be clear, they are often that. For example, can you guess what this Seussian-looking creature is? If you said “crocodile,” you are correct, but you should also probably seek some kind of medical help.]

But bestiaries were also an important tool of the intersecting intellectual concerns of their age: 1) the preservation of ancient knowledge, particularly from Greco-Roman sources, and 2) religious instruction to both clergy and laypersons. Like their cousin, the illuminated book of hours, many bestiaries were actually more focused on using animals to impart moral parables and religious allegories than a strict dissemination of zoological fact, and their detailed illustrations were meant for a indifferently literate population. What’s especially interesting about bestiaries as a whole is how relatively quickly many of the animal allegories homogenized across the medieval European world. Some of this homogeneity comes from major religious thinkers such as Isidore of Seville (560-636 CE) and St. Ambrose of Milan (c. 339-397 CE) introducing and expanding on the use of animal parables in the early centuries of Church history. This gave bestiary compilers a blueprint to follow and led to the same stories being found across the continent.

Foxes in bestiaries are a good example of this. Aside from traditional folk notions of foxes as crafty and deceitful, the bestiary texts will tie a supposed natural trait of the animal—that they play dead to attract prey, which they then attack (see above)—to the way the Devil will snare all those who live by the flesh (the prey who are attracted to the fox’s “dead” body) alone. The text would then likely cite biblical references to bring the parable back to scripture. This could be something equally allegorical like Romans 8:13 (“That you may know this because if you live according to the flesh, you shall die…”), or something more literal like Psalm 62:10-11 (“They shall go into the lower parts of the earth: they shall be delivered into the hands of the sword, they shall be the portions of foxes”).

Yet at the same time, while much of the animal facts are questionable or outright false, this is not simply because the monks in a monastery in Cornwall had never seen a hippo before and wanted to cram it full of religious symbolism.

[Okay, some of this is because they’d never seen a hippo before…]

Much of the bestiary texts that aren’t biblical come from major surviving ancient sources like Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (1st century CE), Herodotus’s Histories (c. 5th BCE), and the works of Aelian (3rd century CE) and Aristotle (4th century BCE). And while Pliny and Aristotle were on the cutting edge of premodern science, we obviously know now that not all of their information was accurate. Some of this was because of these men’s own limited ability to observe certain animals like elephants, but also because of logical fallacies such as thinking that rotting meat on its own produced insects like flies and bees, rather than merely providing the necessary food for larvae.

[Aristotle also mistakenly believed that the reproductive ruler of a bee colony was male rather than female. This was likely because the philosopher simply anthropomorphized bees based on human behavior (i.e., human men are generally larger than women, as a queen bee is compared to a hive’s workers, and because human society was patriarchal, it probably didn’t occur to him that bee society might be different.)]

Another animal fact that jumps from ancient folks to the medieval world the idea that female bears give birth to lumps of flesh that they then must lick into the shape of their “proper” cubs. This is cited by many ancient authors, including a (rare) delightful anecdote from the historian/gossip columnist Suetonius, who claims that Virgil described the creative process for his poetry as analogous to him as a mother bear licking his verses into shape. This sounds silly until you think of how “un-bear-like” bear cubs look when they’re born (see the baby panda below). It is somewhat logical to watch a little bald, blind, hairless bear cub and how the mother will groom it to keep it warm, and jump to the conclusion that she is turning it into a “real” bear cub.

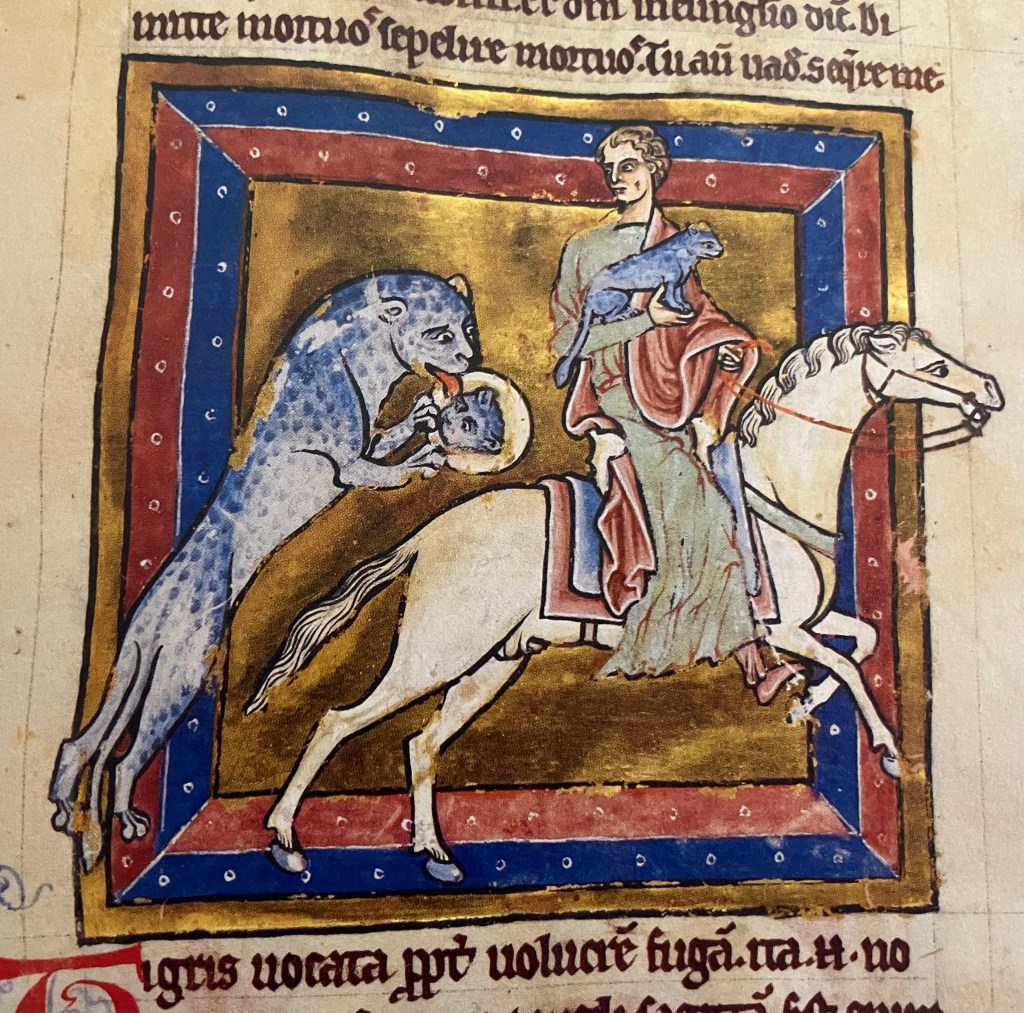

Lions are a great example of how bestiaries braided this ancient pagan knowledge together with religious allegory. As the proverbial “king of beasts,” lions were presented as a representation of Jesus Christ, the lord of all creation. Lions were believed to be able to use their tails to sweep their tracks away when pursued, which was meant to represent how Christ was able to mask his divinity and avoid the snares of this world; likewise, lions’ supposed ability to sleep with their eyes open was analogous to Christ’s unsleeping god nature. Lions are another animal that ancients had odd notions about their reproduction. Worse than the flesh lump bear cubs, ancient scientists believed that all lion cubs were born dead, and the male lion needed to literally breathe life into them. This is why almost every bestiary will have a picture of an adult lion appearing to be performing CPR on a smaller lion (see below). This was turned into a metaphor for how all people are born spiritually “dead” from their mortal, sinning mother, and only Christ, through his death and resurrection, can give us the “breath” of eternal life in heaven.

[A male lion breathes his cub back to life]

[A virgin ensnares a unicorn. Some medieval folk belief thought that the virgin also needed to be naked for best results. Which definitely sounds like something a bunch of young men would have come up with to convince a girl to take her clothes off in the middle of the woods…]

Medieval bestiaries also had a whole host of imaginary creatures. Some of these were deeply allegorical animals like dragons (representatives of the Devil) and unicorns (symbolic of the purity and sacrifice of Christ), but others were simply weird things that travelers had supposedly seen in less verifiable locations like India. These included the hydrus, an Egyptian snake-thing that supposedly embedded itself in Nile crocodiles and burst out of their stomachs like the aliens from Alien; the bonnacon, a maned bull that, depending on the source, either explosively farted or defecated to evade capture; and the parandrus, a Scythian deer/elk who could change is fur color like a chameleon (even Julius Caesar claims to have seen that one).

[A hydrus bursting out of another crocodile of questionable biology. Hydri were also considered another allegory for Christ’s resurrection from the depths of Hell.]

[A bonnacon who frankly looks rather embarrassed that things have escalated to this point. As the oldest reference to the bonnacon comes from Pliny, this one definitely feels like it just might have been filling a need that Romans and medieval folks shared: the appreciation for a good scatological joke.]

[A parandrus of a different color]

As my remark about the bonnacon and our (as in almost every culture’s) ancestors’ enduring love for toilet humor might indicate, there is a growing body of research in ancient, and especially medieval, studies that questions the idea that medieval people believed that all of the made up fantastic creatures in bestiaries were real. Several bestiaries seem to conflate unicorns and rhinoceroses in a way that makes them the same animal (and any differences in appearance are more due to lack of practical exposure for the monk drawing it). Pre-modern people were just as prone to doodling as we are, and reality has never stopped us. I mean, half the internet is pictures of anime cat girls—but that doesn’t mean contemporary people think they’re real.

[Well, most of us don’t…]

To wrap up, I just want include some extra miscellaneous bestiary illuminations that I think are interesting or funny. Some these tie back into the themes we’ve been exploring, some are just cool—but this way you can get a little more of a sense of the breadth of both the animals in a typical bestiary and the different art styles between codices.

[Tigers are more likely to have spots than stripes in a medieval bestiary, but they also have a very consistent folklore attached to them, which is that they are easily distracted by their reflection. This can be a religious allegory for the pitfalls of vanity, but mostly it’s used to explain if you want to capture a tiger cub, the best way to do that is to throw a mirror at the mother, who will mistake her own reflection for her child and therefore give you time to make your escape. I don’t know how often this was coming up in medieval France, but there you go.]

[Another weird hunting tip comes with the entry on beavers. Before Europeans were eradicating them on 3+ continents for their heavy, waterproof fur, beavers were being primarily hunted for their testicles, which were supposedly medically valuable. Therefore, in order to save their lives from hunters, beavers were thought to gnaw off their own testicles and fling them at pursuers to make their getaway. And if an already castrated beaver was being chased by a hunter, it would lift up its hind leg to show that the good stuff was already gone. Either way, bestiaries say this is where the beaver’s Latin name/genus, castor, comes from (castrando – to castrate).]

[Is this manuscript marginalia, or is it a Boar Vessel 600-500 BC Etruscan Ceramic in pants? Who can say?]

[Here, I just love the style of this walrus or whale, in part because it is inadvertently extremely similar to indigenous Inuit art of the same animals. The biblical story of the prophet Jonah and the whale was treated in bestiaries as something very likely to happen to you, so many of them describe in great detail how to rescue yourself if you are ever accidentally swallowed by a whale.]

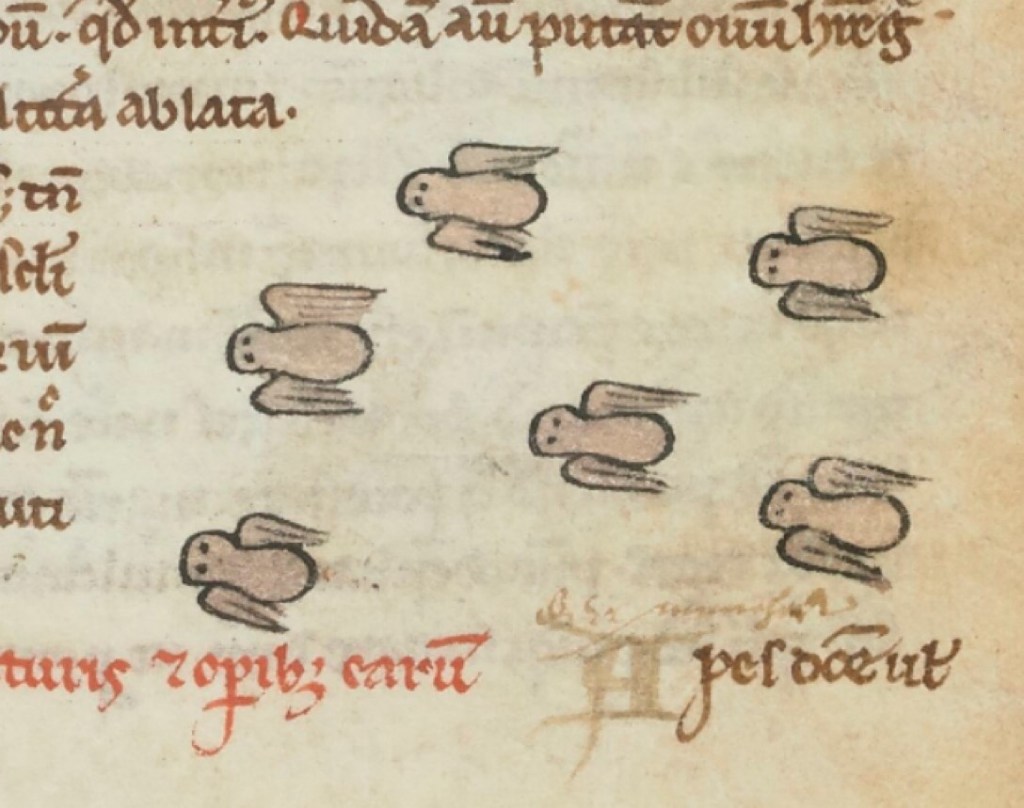

[Another fantastic creature is the caladrius, a large, white bird that was a kind of medical augury. A caladrius was sat on a sick person, and if the bird looked at the patient, they would recover. However, if the bird turned its head away, the patient would die. Church allegory for this would be the caladrius as Christ, who gazes compassionately upon the repentant “sick” sinner, but turns his mercy from the unrepentant, who suffer eternal death without His grace.]

[Medieval monks in Northern Europe taking a stab at what scorpions look like]

[Eagles, king of birds as lions are king of beasts, are always Christ symbols. For eagles, this is also because medieval people seem to have believed that in old age, eagles experienced phoenix-like rejuvenation. When they become too old, eagles were thought to fly close to the sun and burn their old feathers off, after which they dived into a body of water to bathe three times and be reborn with new vigor. That’s great for the eagles, but it does lead to a bunch of illustrations of eagles looking like plucked chickens nosediving into water in these books.]

[There was a (delightful) popular ancient/medieval fallacy that hedgehogs’ bristles were used by them to carry food back their burrows. This one looks like they are foraging apples, or maybe cheese balls, for the winter.]

[Another manuscript clerk who went Full Seuss when somebody described a giraffe’s neck to him]

[And when in doubt, if you tell them it can cure their diseases, people will line up to meet your enormous bat and stop asking so many questions about the number of limbs it has…]

Leave a comment