In February of last year, I wrote an entry that was in the macro about authorial ethics in historical fiction and in the micro about fictional portrayals of Anne Frank specifically. I was pleased that entry seems to have connected with a number of you, both because I think it was an interesting and important issue, but also because I had hoped to present that particular topic with the appropriate level of sensitivity and nuance (and not in one of my more irreverent moods…). Given how I came out of that discussion perhaps even more trepidatious than ever about Holocaust literature as a fiction genre, I had assumed this was a topic I was unlikely to return to. But here we are.

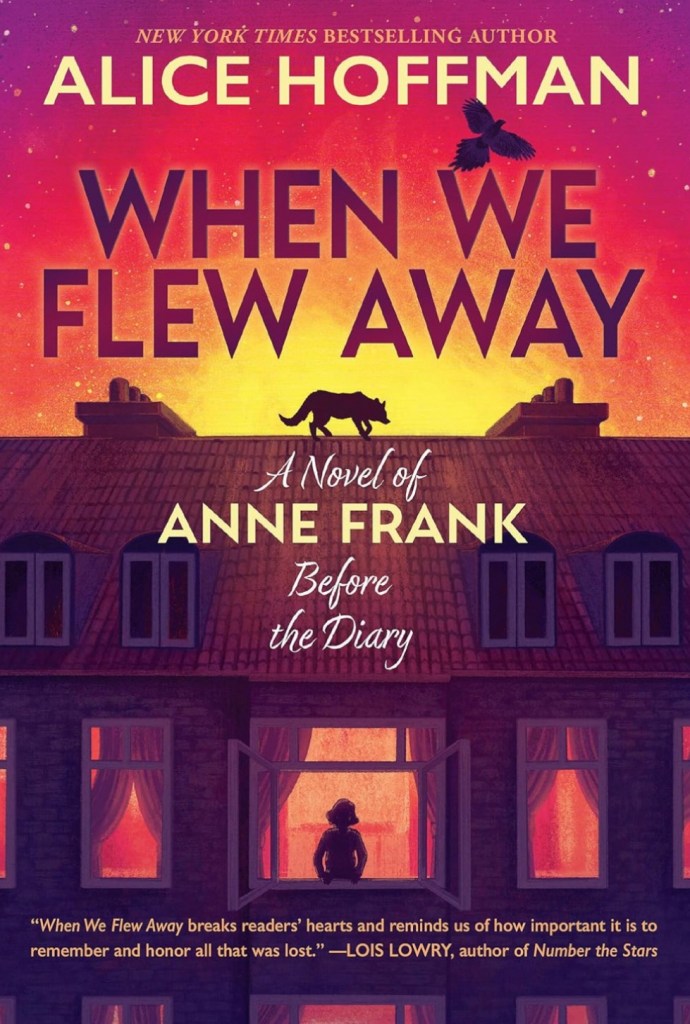

As an on-again-off-again reader of her books, I received several push notifications from various places over the summer that Alice Hoffman had a new novel, When We Flew Away, coming out in September that was “a novel of Anne Frank before the diary.” Though I had become hesitant to get involved with Holocaust fiction again broadly and Anne-centric fiction specifically, I was intrigued by the idea of yet another novel about Anne, especially by a writer with whose work I had some previous experience. And I thought that this was maybe a good opportunity to revisit this topic through the lens of a truly contemporary perspective with such a recently released book: is Holocaust fiction evolving as a genre? Are the same issues we’ve talked about previously still present? And, again, is fictional Anne a character we should keep reviving?

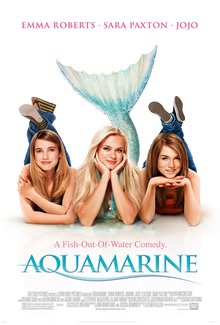

But before we get too deep into the weeds of those larger concerns, I should offer some context. For those of you who aren’t familiar with her, Alice Hoffman is the bestselling author of over forty books, the most famous of which is probably Practical Magic (1995), which was the basis of the same-named 1998 movie starring Sandra Bullock and Nicole Kidman. Most of her novels can be categorized as literary or romantic fiction, with many containing elements of historical fantasy and magic realism. Although primarily known as a writer of adult fiction, she has had success in young adult and children’s fiction as well, there probably best known for her 2001 teen mermaid novel, Aquamarine, which was also made into a (largely unrelated) movie in 2006.

[Hang onto your film rights, kids…]

More related to our discussion, perhaps, I should also note that Hoffman, like Philip Roth and Shalom Auslander from our last conversation, is an American of Jewish descent who has tackled Jewish stories before in her work. I haven’t been able to determine if Hoffman specifically identifies as Jewish herself, but much of her cultural interest in Jewish history seems to come from her grandmother, who was a Jewish immigrant from Russia. I came to Hoffman’s work through perhaps her other most recognized novel, The Dovekeepers (2011), which I loved—a historical novel about the siege of Masada during the First Jewish-Roman War (72-4 CE). The reading high from that one I’ve been chasing ever since in Hoffman’s oeuvre, with mixed results. For example, I finally got around to reading her 2015 novel The Marriage of Opposites a few months ago, which is largely about the Impressionist painter Camille Pissarro’s mother, Rachel, and the Jewish expatriate community in St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, and thought it was merely okay. But Hoffman is one of the writers whose prose is always beautiful, even if the particular story doesn’t grab me.

[She’s somebody whose writing is often described as “lush,” like Pissarro’s paintings of his native St. Thomas (Landscape with Farmhouses and Palm Trees, c. 1853)]

I thought that I hadn’t read any of her young adult fiction, but it turns out that 2005’s The Foretelling, a reimagining of the Greek Amazon mythos—which I also read this summer—is classified as YA. That one was also only fine; I loved the idea, but I just wasn’t sucked into the story the way I was with Dovekeepers. And it didn’t especially strike me as YA, which is I suppose a double-edged sword. Modern young adult fiction was really just getting going when I was in the right age group for it, but I missed a lot of mid 1990s/early 2000s YA because I’d already surpassed those reading levels and was more interested in adult fiction. But I also support YA that is more literary in tone—one, for variety’s sake, and two, because I think middle readers and teenagers don’t need to be spoon fed. But I can’t escape the thought that Hoffman’s publishers classified The Foretelling as YA because the protagonist is a young adult and because the book is very short (192 pages), as opposed to any specific genre considerations.

Anyway, I was also unaware that When We Flew Away was a YA novel when I put in for it at my library, with some ad copy even aiming it at an even younger middle reader audience. I do read some YA, but I don’t generally read what I’d call an abundance of it. This isn’t me trying to come off snooty, it’s simply a statement of fact. Some of this is left over from largely skipping over the genre as a younger person, and some of it is, honestly, to avoid going in too hard ratings-wise on stories that are (at least in theory, anyway) not written for me, an adult reader. Older readers have long been accused of horning in on YA genres, especially in fantasy/romantasy, pushing those books in themes, content, and general verve out of their target demographics, and while I do believe people should read what they enjoy, there is a critique to be made of adults being unwilling to expand their reading palates. But I also recognize the potential optics of me, a grown-ass woman, rating a book for teenagers low because I didn’t find it, as an adult, interesting or challenging. But there are middle reader/YA books I do hold affection for, so I was prepared to go into When We Flew Away with all my reader baggage vis à vis Holocaust fiction and YA generally acknowledged, and to give it a fair hearing.

But here’s the thing, dear readers, I just didn’t feel this one. Something that I seem to be rather alone with, as most of the reviews I’ve come across, both professional and public, are pretty uniformly positive. Hoffman’s textual prose remains evocative, full of dreamy asides about the world around Anne in Amsterdam, but this almost clashes with the (I assume intentionally) simplistic dialogue of Anne and the other characters. While the print is large-spaced, this does clock in at almost three hundred pages, which is doable obviously for YA, but is pretty lengthy for a middle reader. And I just don’t know how engaging the average reader in either group will find the gentle, meandering plot. I mean, I would’ve probably been game at that age, but I’ve always had unusual tastes, Anastasia.

I would, of course, be the last person to try to suggest that we shouldn’t challenge younger readers in regards to elements like plot, pacing, and language—but I do think it’s difficult to do all of those things in the same book. Hoffman deliberately chose to set this story in the couple of years before the Franks went into hiding, the event on which the book ends, which is a fascinating idea, for the record. Just as I found Roth and Auslander’s decision to focus on a post-death Anne, centering on a pre-diary Anne is a fresh look at a told story, but you have to do something interesting with it. WWFA probably couldn’t have done anything remotely as provocative as those other books, given its the age of its protagonist and proposed audience, as well as the fact that Hoffman was writing this with the (obviously desired) blessing of The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, but Hoffman, seemingly too afraid to make a choice, is too conservative where she could be bold and is too fanciful where she should be more grounded.

Very little happens in terms of action in WWFA, which isn’t necessarily a fatal flaw, but so much of what does turns into scenes that are little more than slightly fleshed out versions of events that Anne records in the few of her diary entries that predate the family going into hiding. Anne wants to go eat ice cream at Oases, Anne is jealous of her sister Margot, Anne has variations on the same fights with her mother. This doesn’t feel like an Anne we don’t know, nor one about whom we’re learning anything new. Perspective sometimes shifts to Otto or Edith Frank, but a lot of particularly the latter seems aimed at trying to soften the relationship between Anne and her mother and give them a catharsis, which in light of the continued friction between the two literally to the end of their lives, feels disingenuous. Not to mention that Hoffman essentially ends up rebuilding the exact sort of censorship Otto Frank applied to earlier published editions of his daughter’s diary in regards to her relationship with Edith, something contemporary definitive editions have spent the decades since Otto’s death trying to gently strip away.

What narrative tension exists almost entirely rests in the amount of background the reader brings with them, as do much of the, for lack of a better term, Easter eggs, that Hoffman scatters about. Anne just lives her life, and if you find any of that ominous, that’s because you already know what’s going to happen. If the reader knows Anne’s story, they are looking for references to Oases and Opekta and Hello Silberberg and Miep Gies, just waiting for Kitty to given and the deportation letter for Margot to arrive, but since the book ends without the true denouement of Anne’s fate, it just feels like cheap, dramatic sentimentality. On its own, a wistful lack of resolution can be poignant, but not after a story where very little else happened.

And then there’s the touch of magic realism. Anne sees black moths everywhere that grow in number and ominousness as the Nazi restrictions on Dutch Jews grow, and metaphorical wolves and dark Grimm-esque forests weave in and out of the moving narrative and sectional asides, but nothing comes of any of it. The moths don’t influence the plot, so they might as well be metaphorical too. Even as someone who liked, say, Jane Yolen’s Briar Rose, and as the one person who still doesn’t groan at magical realism as a genre, I just don’t think it’s suited to Holocaust literature. Metaphor away, but introducing magical elements into the Holocaust just increases the cruelty of a terribly cruel situation. It becomes one more thing that failed the Jews and the other minorities of Europe, and shifts the focus, however minutely, away from the active malice of the perpetrators and the cowardly acquiescence of the bystanders.

All of this is mostly a long-winded, slightly disjointed attempt to say that rather than bad, I just found WWFA unnecessary, especially for the stated audience. We already have the best YA/middle reader book about Anne Frank—it’s The Diary of a Young Girl. Hoffman is a gifted writer, but no one has ever topped Anne as the narrator of her life. Hoffman admits in an afterwords that we don’t know much about Anne’s life before the diary years, and what we do know is information Anne drops in the diary. But Hoffman clearly shares at least some of my reticence for whole-cloth fabrication in this genre, so she is afraid to introduce anything that doesn’t emanate from the diary—the ur-text. So WWFA is caught in this paradox where it isn’t interesting if you don’t have the diary as context, but having read the diary renders the novel superfluous.

The whole time I was reading it, I kept saying to myself, “Why is this? Why does this exist?” And I know the answer is that, as we’ve previously mentioned, WWII/Holocaust fiction is one of the few true cash cows in the historical fiction genre, and Anne Frank is a perpetual darling subgenre, particularly for young readers, to educate them about the Holocaust. But The Diary of a Young Girl isn’t some obscure text that we’re trying to lure kids back to; it’s one of the most popular books ever written. And if there’s been a drop off in schools assigning/introducing it to Gen Z/Alpha, I’d rather energy be spent bringing it back into curriculums rather than slipping it to readers in a watered down, fictionalize format. Worse still, WWFA has some of the earmarks of those unfortunately rampant novels which are marketed as YA, but are really intended for a YA-consuming adult readership. Thankfully not in the luridly sexual way that usually means, but more of in that YA nostalgia way. This could have been a tight novella that might have appealed to both young readers and adults, and instead it feels like a padded appendix to the diary that somehow pleases neither audience. It might be too abstract and rambly for kids, but too simplistic for adults.

But all is not lost, dear readers. I might not think WWFA is a particularly good way to introduce your younger readers to the Holocaust, but I do have some other recommendations to fill that void. One of which is even mentioned on the cover of WWFA.

[What a twist!]

Yes, that would be Lois Lowry’s 1989 seminal YA Holocaust novel, Number the Stars, which is about a young Danish Christian girl, Annemarie, and her Jewish friend, Ellen, set against the remarkable true story of the evacuation of Denmark’s Jews to Sweden in 1943. I loved it as a kid, and having had the opportunity to reread it after WWFA, it was a delight to find that it still holds up and it was such a palette cleanser just in terms of a well-written story. Lowry is such a master YA writer—she writes with her audience in mind, but in a way that is never trite or condescending. Annemarie and Ellen are brave, but not in an unbelievable or deus ex machina way. There is action and suspense, but the story slows frequently into quiet or humorous moments that are never misplaced. It is 132 pages, and it feels like so much happens and yet not a word is wasted. And by setting a fictional story in a surprisingly faithful account of a real Resistance event and not in the camps (like Briar Rose, or one of Yolen’s other YA books, The Devil’s Arithmetic), Lowry manages to avoid the ethical pitfalls of both exaggerated Nazi resistance novels and camp novels that play too fast and loose with facts.

Also, while I’d always recommend The Diary of a Young Girl to almost any reading-age child, if you want to ease a child into Anne’s story outside of her diary, Ari Folman’s graphic novel of the diary (Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation) is really wonderful and does a beautiful job of capturing Anne’s essence in a visual medium. Like the diary itself, the graphic novel has come under frequent banning pressure because Folman doesn’t shy away from Anne’s curiosity about romantic relationships and her own body, but neither work talks/depicts these topics in a prurient or graphic (ha) way. And as a supplement to the diary, or as a great resource on its own, Ruud van der Rol’s Anne Frank Beyond the Diary: A Photographic Remembrance is a fabulous middle grade reference book about Anne, the Holocaust, and World War II. It has a ton of pictures of the Franks, especially in those foggy early years; one of them, a picture of Anne leaving Miep and Jan Gies’ wedding, was a scene Hoffman described in WWFA, and I could still picture the photo and Anne’s outfit vividly. It also does a wonderful job of placing the Franks in their moment in history. Much of what I first learned about the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands and Final Solution I picked up from this book, which is serious and factual about these events, but in what I think is an age-appropriate way.

All of this said, although I didn’t especially enjoy When We Flew Away myself, it’s hard for me to definitively warn people off from reading it. I recognize there are many voracious middle grade readers who, given the current climate in YA, have trouble finding a lot of “advanced” books that aren’t filled with sex and violence. This might be a good “grown up” type book for them, especially if they have an adult willing to read it in tandem with them, with whom they can discuss the more abstract aspects of Hoffman’s writing. Hoffman’s Anne isn’t her most dynamic iteration, but she is still an Anne who is bright and curious and very much in the process of figuring out the business of life, which is always relatable to her peer group. And although it is merely a pale shadow of it, WWFA could still be used as a companion to The Diary of a Young Girl for a younger reader, or an adult perhaps more forgiving than me.

For me, reading WWFA reminded me of being in the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, which is the office building where the Franks, van Pels, and Fritz Pfeffer hid for two years before they were discovered and deported. It was moving, of course—it’s hard not to be touched by Anne’s magazine cutouts still on her bedroom wall, or to see Kitty in the flesh (gingham)—but nothing can really replicate that first experience of reading Anne’s diary and falling into her story. You can chase that moment of pure connection, see the physical diary with your own eyes, read biographies and novels, but I feel like you’ll chase in vain. Just as Roth and Auslander tried to show that the historical Anne had transcended history and even death to be her own context, I feel like her soul as a writer has transcended imitation and even the totem of her fame (Kitty herself). Anne is Anne, accept no substitutions.

Leave a comment