“Tell the angel who will watch over your future destiny, Morrel, to pray sometimes for a man who, like Satan, thought himself, for an instant, equal to God; but who now acknowledges, with Christian humility, that God alone possesses supreme power and infinite wisdom.” – The Count of Monte Cristo, chapter 117

“You’ll like it; it’s about a prison break.” – Andy Dufresne, The Shawshank Redemption

Like most things in this life, reading is a skill, and one I fervently believe can be honed as well as simply learned. People who know me now often seem to have a lot of trouble believing that I did not spring from the womb with six books in hand and several hundred books on a TBR list, but it’s true. For the first eight or so years of my life, I deeply enjoyed being read to, but I don’t really think that I was a particularly exceptional reader on my own. Then in third grade, my teacher, Mrs. Kin, gave me one of the American Girl books (Happy Birthday, Samantha), and it was like a switch flipped. I was suddenly insatiable; which is mostly funny because in hindsight, I would not consider Samantha my favorite American Girl (Felicity, btw—yes, I know that’s got baggage…). I tore through most of my elementary school’s history and biography sections within the next year and a half, and by fifth grade, I was consistently reading adult books. But even under this almost exponential acceleration, I still had to build my reading skills, and that between-year in fourth grade was kind of a literary no man’s land where I was most exposed to middle-grade literature and children’s adaptations of adult classics.

Unlike Mrs. Kin, I found my fourth grade teacher, Miss Burns, somewhat intimidating, but she did keep in her classroom an extensive collection of the Illustrated Classics series published by Moby Books in the 1970s. The Illustrated Classics were almost pocket-sized, abridged adaptations of literary classics aimed at children. They were clearly cheap, but many of them were my earliest exposure to many famous works.

Many of the titles chosen for this series are the usual rogues’ gallery of 19th century novels most often used to try to ease kids into Great Literature—Treasure Island, Black Beauty, The Call of the Wild, The Secret Garden—but, as you might guess from me name dropping one of them above, the series also contains the most popular of Alexandre Dumas’ historical books, of which The Man in the Iron Mask is the least. The other two, of course, are The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, and both, because of their action-packed plots and Dumas’ own comparatively simple writing style, have long been a staple of juvenile adaptation.

[Because it was the ‘70s, they also did a juvenile adaptation for Ben-Hur, whose plot was partially inspired by The Count of Monte Cristo]

Last fall, my mom was reading The Count of Monte Cristo for the first time and was really enjoying it, and she asked me if I had read it. I was sure that I had, but I didn’t remember very much about it and had consequently marked it as a two stars out of five on Goodreads (often my signal for a book that didn’t leave much of an impression on me, especially if I read it a long time ago). But I was forced to reconsider my decision when my mom, who might be an even more stringent book grader than I am, gave it an enthusiastic five out of five. Now, with almost every one of those Illustrated Classics, I eventually read the adult unabridged version at a later time, but as I racked my brain, I realized that my assessment of Monte Cristo might be based on a tiny abridgment I had read when I was nine. As a result, I decided that once I’d met my reading goals for this year, I’d get my hands on a “real” copy of the novel and give it another go. So, having reached the traditional time of the year that I set aside for longer books and rereads—and having a lot of time to kill traveling back and forth on an Alaskan cruise—I took up again with literature’s second most famous count to see if I couldn’t give him a fairer shake.

[We ended up having a five hour delay on the way out and a two hour delay on the way back on top of our cross-country flights—I had a lot of time to kill…]

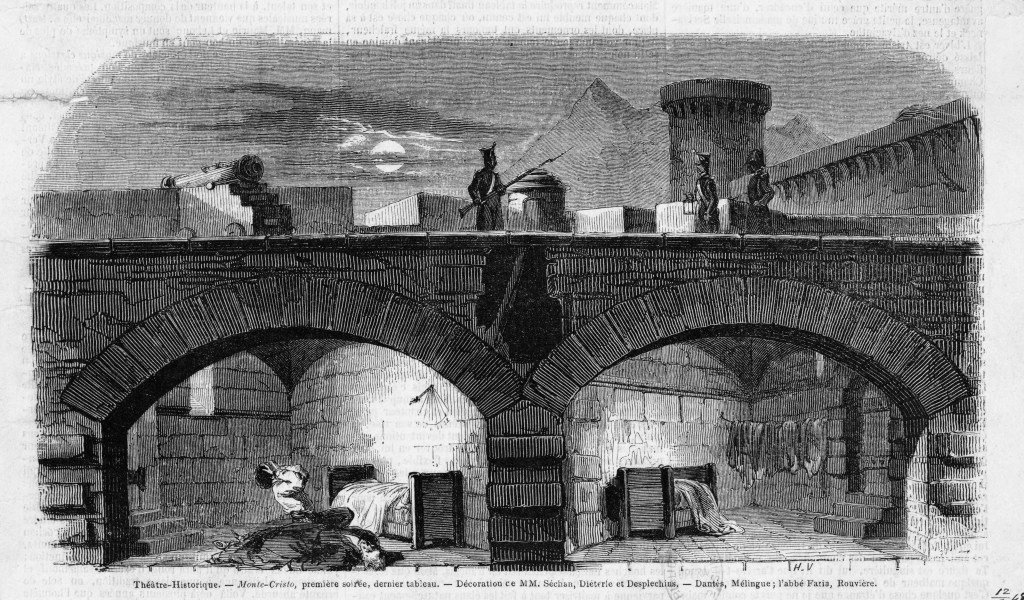

For a quick refresher/introduction, The Count of Monte Cristo is the story of Edmond Dantès, an honest young sailor who enjoys the trust of his merchant employer and the love of his beautiful fiancée, Mercédès. On the eve of their wedding and just after he’s been given command of a ship, Edmond is falsely denounced as a Bonapartist spy by a colleague who wants his job and Mercédès’ jealous cousin who’s in love with her. Sentenced without a trial to indefinite imprisonment by a magistrate trying to protect his own interests, Edmond nearly loses his mind in solitary confinement until he is able to communicate with the prisoner in the next cell, a priest also being held as a political prisoner. The abbé teaches Edmond and promises to share a treasure of mythic proportions with him that is buried on the deserted island of Monte Cristo if they can ever escape the prison. The priest dies, but Edmond escapes in his burial body bag and makes it to Monte Cristo, where he does indeed find a huge treasure. Edmond uses his now limitless wealth to transform himself into the titular count and vows to exact revenge on the men who destroyed his life.

Some of this is Gothic melodrama, but some of Monte Cristo’s plot is based on the real-life case of Pierre Picaud, a French shoemaker falsely accused of being an English spy by envious neighbors, who was left a large fortune by an Italian priest he served while imprisoned, which he then used to sustain himself while he killed the men responsible for his denouncement, before being killed himself by another man tangentially related to the plot. Other parts of the story incorporate the celebrated and unusual life of Dumas’ father, Thomas-Alexandre Dumas, the Haitian-French son of a titled white planter and an enslaved woman. Denied access to his father’s wealth and titles because of his illegitimacy, Dumas entered the military academy with almost nothing and rose to the rank of general during the Republic and the Empire. Tall, handsome, and talented, Dumas senior would personally clash with Napoleon to the extent that when the general was shipwrecked and taken prisoner after the Egyptian campaign, Napoleon would leave him languishing in an enemy dungeon for two years before getting him out. Dumas would return to France, but his health would never recover and he was dead within five years, leaving his son, Alexandre, fatherless at the age of four. Denied even his father’s rightful military pension by Napoleon, Dumas the novelist and his mother would never forgive the emperor. Elements of the elder Dumas’ imprisonment show up in Monte Cristo, but so does the author’s despair at the miserable, undeserved death in poverty of his own father in the death of Edmond’s equally ill and forgotten father.

Right off the bat, Monte Cristo’s reputation as a “juvenile classic” like Musketeers is wild just based on its length. The English translation I read, the well-regarded Penguin edition by Robin Buss originally published in 1996, runs to an eye-watering 1,243 pages—almost twice as many as the respectably hefty 700-odd paged Musketeers.

[I feel like they might have left some stuff out…]

Indeed, the parts I remembered from any adaptation of the plot—Edmond Dantès’ betrayal, his imprisonment for a crime he didn’t commit, his learning about the fabulous secret treasure buried on the island of Monte Cristo and his finding it—all of this takes up less than 250 pages of the novel. You should have seen my face when I realized the part that the kiddie adaptations tend to breeze through, Edmond’s transformation into the enigmatic Count of Monte Cristo and his campaign of retribution against those who stole his life, was going to account for the remaining thousand pages.

But aside from trimming the story down to a more manageable length for a pint-sized audience, something that even many of the early adult versions of the novel do (especially many of the first English translations from the late 19th century) is to greatly bowdlerize what is a pretty dark and even risqué story, particularly for something written in the 1840s. Apart from Edmond’s pitiless revenge quest that turns him into a sort of immovable, proto-Batman, in the course of the plot, there are kidnappings, armed robberies, adulteries, assassinations, rapes, honor killings, several brutal murders, and an attempted infanticide—many of which tend to get massaged out in many adaptations. One of Edmond’s former tormentors is driven to suicide by him, and another goes completely insane. Another character kills four people and herself with poison, including her own young son. It also usually gets lost in translation that our hero owns two slaves (Haydée arguably isn’t really a slave, but that’s how Edmond portrays her to others) in an era where that was not the norm in Europe, and he loves consuming opium and hashish. One whole chapter is devoted to the erotic hashish trip another character experiences while enjoying Edmond’s hospitality.

[It’s all a bit too French for the original Anglo-Victorian audience]

But it’s not the reefer madness, or even the surprising amount of violence that keeps me from being able to second my mom’s 5/5 assessment—it’s how unlikable most of the characters are. I’m a characterization enthusiast and something, positive or negative, has to attract me about at least some character(s) in a story for me to give highest marks, regardless of plot. Like in a lot of Gothic-adjacent stories, many of the Monte Cristo characters are pretty flat, but that wouldn’t necessarily be fatal if I was more compelled by our protagonist.

Edmond is boring when he’s Dantès and vaguely repulsive when he’s Monte Cristo, which, understanding the Byronic milieu of the novel’s development, I know is kind of the point. But I’m also someone who lives for a complex antihero or a villain with a heart of gold, and Count Edmond just doesn’t do it for me. The darkness in Monte Cristo’s heart doesn’t illicit sympathy because when he becomes the count, Edmond ceases to care about anything but his revenge. He does good in principle for the Morrels, Albert, and Haydée, but he keeps his emotions so locked inside and the revelation that any part of his gentle self has truly survived takes so long to be revealed that by the time it happens, it all feels too late to love him as a character. To use a very loosely contemporary analogy, even good ol’ Phantom of the Opera Erik loves music in addition to being an obsessive asshole. Monte Cristo doesn’t seem to want anything except the downfall of his tormentors. It takes the ancillary murder of a child for him to finally start to wonder if maybe he’s taken things too far, but because Dumas spent the previous six hundred pages describing this child as the worst sort of spoiled little shit imaginable, it ends up feeling cheap and manipulative (on the reader) instead of poignant.

And I think that this is where the length becomes a problem. We spend so much more time with Edmond as Monte Cristo than we do with his “true” self, that it’s hard to form an emotional connection with a character who spends eight hundred and fifty pages mostly being a dandily-dressed Terminator. It takes so long for the turn back to Edmond to happen, that when it does occur, it feels like we hardly know this person. Worse still, as someone who could not remember how this all ended, it took so long that I started to be genuinely afraid that I might be reading a twelve hundred-page revenge play where no one was going to grow or learn anything. I’m not naïve—I know it is unrealistic to have Edmond simply be unaffected by the unjust tragedy that has befallen him. Not to mention it would be a dull story.

But what is ostensibly a happy ending is undermined by the sheer scale of horrors that proceed it. Haydée, Edmond’s Greek protégé, is strong, beautiful, and virtuous, but she cannot possibly fix the broken creature that Dumas tries to convince us in the last fifty pages of this doorstopper is still capable of sustained love. In the continuation of the quote I used in my flavor text, Edmond claims that “he who felt the deepest grief is best able to experience supreme happiness”, and while there is some truth to this, as usual, the Count of Monte Cristo takes everything too far to the extreme. To have experienced grief and hardship can bring one greater gratitude when joy returns, but Edmond uses this logic to justify driving a man that he claims to love like a son to the very brink of suicide before finally revealing that his fiancée wasn’t murdered like he believed. Because even a “healed” Monte Cristo’s love has this Old Testament cruelty to it, I can’t look on Edmond and Haydée’s ship sailing away into the horizon with anything but a lingering unease. Maybe Dumas intended this, maybe he didn’t.

I might not have savored this complexity enough to love the book, but that doesn’t mean that the reread was a waste or that there weren’t things I liked. One thing that I found rather delightful—and another that has routinely been excised from the text by adaption—was Eugénie Danglars, the strongly lesbian-coded daughter of one of Edmond’s antagonists. Unlike, say, to use another near-contemporary comparison, Marian Halcombe in Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White (which I love, for the record) and other lesbian-coded women in 19th century fiction, Dumas does not go out of his way to make Eugénie ugly or overly mannish. While she is tall and athletically built compared to the other petite and waifish women in the book, she is still described as beautiful, with “lustrous…rebellious” black hair and eyes to match, with “quizzical” eyebrows, and a suffer-no-fools manner that intimidates most of the young men around her, who compare her to the goddess Diana (Monte Cristo, 599-600), clearly referencing the famous Diana of Versailles statue now in the Louvre. Where the other young woman are sort of passively beautiful with few notions or interests, Eugénie is passionate about music and has aspirations of being an artist.

[The Diana of Versailles]

Even more explicit than her appearance, which would have marked her out in midcentury literature on its own, Dumas takes it a step further by having Eugénie as strongly disinclined towards marriage as she is strongly attached to her young music teacher, Louise d’Armilly, who is the only person she willing spends time with in the novel. Obviously, this is still the 1840s, so there’s a lot of talk about what “close companions” the two young women are, but even the other characters seem to know what’s up.

It would have been easy for Dumas, if he was disapproving of this relationship, to punish Eugénie for not being like other girls, especially since she’s the daughter of one of the men in Edmond’s crosshairs. Instead, when Edmond puts the wheels of her father’s demise in motion, Eugénie uses this fall from grace as an opportunity rather than a calamity. Having carefully socked away a nest egg of money, she runs away with Louise dressed as a man with forged passports obtained from Edmond so the two of them can start a new life together abroad as professional musicians. After an unexpected run-in with the fake prince she was supposed to marry, the two women do have to suffer the minor embarrassment of being publicly exposed for what they are to get away from him, but the plot still allows them to cross the French border into Belgium and have their happily ever after. An extremely progressive ending for two queer characters in a 19th century novel.

So to wrap up, I’m sure you’re all wondering after all this flip flopping whether or not I ended up revising my 2/5 rating for The Count of Monte Cristo, having now read and digested the unabridged story. And I’m happy to report that I am bumping this from a very mid 2/5 to what I call the “Anna Karenina 4”—meaning that I liked the writing/story but generally disliked the characters themselves. Not too bad of an upgrade. If you’re not a velocireader like me, it might take you some time, but I do think Monte Cristo is worth reading; it does have some poetical things to say about revenge and forgiveness, particularly from an author not usually renowned for being philosophical. And if you love gothic horror, psychological thrillers, murder mysteries, adventure stories, Romantic melodrama, and Shakespearean levels of violence, Monte Cristo has you covered. Truly a novel with a little something for everyone.

[Even dogs]

Leave a comment