I really was going to move on from Egyptian content again for a bit (I like to keep you guessing), but then I went for a rare summer jaunt down to CMOA/CMNH just to stretch my legs a bit before Oakland fills up for the next semester. I usually don’t go to the museums much in the summer—one, because the summer tends to be full of other, seasonal activities, and two, because it tends to be a kind of fallow period at the museums while they round out the exhibit year and do gallery refreshes.

[They can keep making these dividers bigger, but I’ll keep broadcasting them until they find a better storage solution for their event furniture than stuffing it in an active gallery space. This isn’t on the staff/curators—this is a management issue. C’mon folks, if you want people to be invested in the Hall of Architecture, stop treating it like a closet. It used to be funny, but now it’s just kind of sad that this section hasn’t been walkable since before the pandemic…]

Even though the Walton Hall of Egypt is still closed, I usually start my museum days up on the third floor and work my way down. This helps avoid any crowding as that’s typically the opposite direction everyone else takes, plus I get those four flights of stairs out of the way early. Anyway, I wasn’t expecting much up there, certainly not in the new category, but I was pleasantly surprised by a fresh Egyptology pop-up station out in the hallway.

[Surprise!]

Designed to showcase different aspects of Walton Hall’s collection with a focus on tracing collection provenance while renovations continue, I’ve been showing these off as they come through, and we have seen that there has been a bit of variance in interest and quality. But this newest one is a real winner, as it highlights a rarely considered aspect of Egyptology—the Egyptian oases—and in this case, perhaps one of the least known, that of Siwa, possibly past and present Egypt’s most remote city, and its unique history and culture. As I briefly mentioned in my post about ancient divination, the oasis at Siwa is probably most famous for its oracular priesthood of Amun, the one that told Alexander the Great that he was the son of the god and rightful ruler of Egypt following his defeat of the empire’s Persian rulers. But I thought with the pop-up as a prompt, we’d take a closer look at Siwa as an Egypt that’s both a little of what you think you know and maybe more that you didn’t even know you were missing.

[Siwa in relation to the rest of Egypt]

As you can see, Siwa is location on the extreme northwestern border between Egypt and Libya. To give you a sense of distance, Siwa is ~335 miles southwest of Alexandria, and only ~31 miles east of the modern Libyan border. The city, both ancient and modern, exists as an oasis created in a depressive flood plain by the confluence of natural springs and two saltwater lakes, Zaytoun Lake to the east and Siwa Lake to the west. Many of the springs are naturally occurring artesian wells fed by aquifers formed in the local clay and limestone, but these have been augmented throughout history by man-made irrigation.

[Siwa from space]

While situated within both modern Egypt and territory typically controlled by ancient Egypt, Siwa’s remoteness has contributed to its distinctive culture in both eras. There are records of human settlement in the oasis from as far back as 10,000 BCE, but the earliest certain contact with ancient Egypt didn’t occur until the 600s BCE, because we have the remains of a necropolis from the 26th dynasty (664-525 BCE) at Siwa from this period. That said, ancient Egypt’s fluid approach to its borders make it likely that at least trading and passing military contact with the inhabitants of the oasis occurred much earlier. Throughout its long history, Egypt was cyclically at war with the various Libyan tribes, and Siwa would have been, at the minimum, an important refueling station for the Egyptian army between the Nile Valley and the Libyan Plateau just beyond the oasis. So even if Egypt wasn’t officially in control of Siwa as a part of its empire until comparatively late, it is probable that they had some kind of ongoing treaty arrangement with the local tribal authority, much in the way they did with various Bedouin communities.

Not long after Siwa enters the Egyptian records, we also have evidence that the oasis was in contact with the Greeks, through the Greco-Phoenician settlement in Cyrene (Κυρήνη) on the northern coast of Libya. According to Herodotus (5th century BCE), the original Cyrenian Greeks were from Crete or Sparta, but like many ancient foundational stories, there’s a hefty dose of mythology thrown in for good measure, so much of what we “know” about early Cyrene is up for debate. But whoever the Greeks were, we do know they were in contact with Siwa. You might wonder why the coastal Cyrenians would bother to trudge across the desert to Siwa, but we haven’t mentioned yet that the oasis and the surrounding valley of Siwa has also always been a major producer of date palms and olives—enough to support a serious agricultural export system. Siwa was a closer location for Greek traders for these goods than Egypt would have been, and once Cyrene became an Egyptian colonial territory under the Ptolemies, Siwa’s garden spot would have been an important economic link between the two borders of the empire.

This produce is possibly where Siwa gets its Middle Egyptian name: sḫ.t-ỉm3w (Shet-Jamau), “Field of Trees.” Siwa(h) itself is the later early modern Arabic name (which I’m mainly using because, like Giza, it’s simply the most familiar). We’re not entirely sure where this Arabic name comes from, but it may be from *Se, the proto-Berber name that early Muslim scholars recorded as Santariyyah (سنترية), and “Siwa” is a sort of linguistic blending of the local Berber into Arabic.

Because the indigenous people of Siwa aren’t ethnic Egyptians (whatever that means in the inscrutable ancient sense)—they’re a Berber group (modernly, Imazighen (أمازيغ)/Amazigh). The Berbers, who we discussed in my post about Mauretania, are arguably the original Greek “barbarians” (hence their western name), and despite that pejorative from the Aegean, their culture is one of the cradles of humanity. The Imazighen as a civilization can trace their roots to the Stone Age, and they have inhabited the breadth of North Africa from then until this very moment. Today, roughly 36 million people identify as Imazighen, most of whom live in Morocco and Algeria, but Imazighen identity is driven more by a connection to one of the twenty or so Afroasiatic dialects that have been gathered under the linguistic umbrella of Tamaziɣt than by a specific culture or geography. These Tamaziɣt languages are so old and diversely located that many of them are mutually unintelligible, but they share the same prehistoric roots, and when we say “mutually unintelligible,” we mean in the way that many of the Romance languages aren’t entirely comprehensible to one another without additional study. Different Tamaziɣt speakers are like French speakers comprehending Spanish or Italian—they might get the gist of what is being conveyed, but could miss nuances or regional idiosyncrasies.

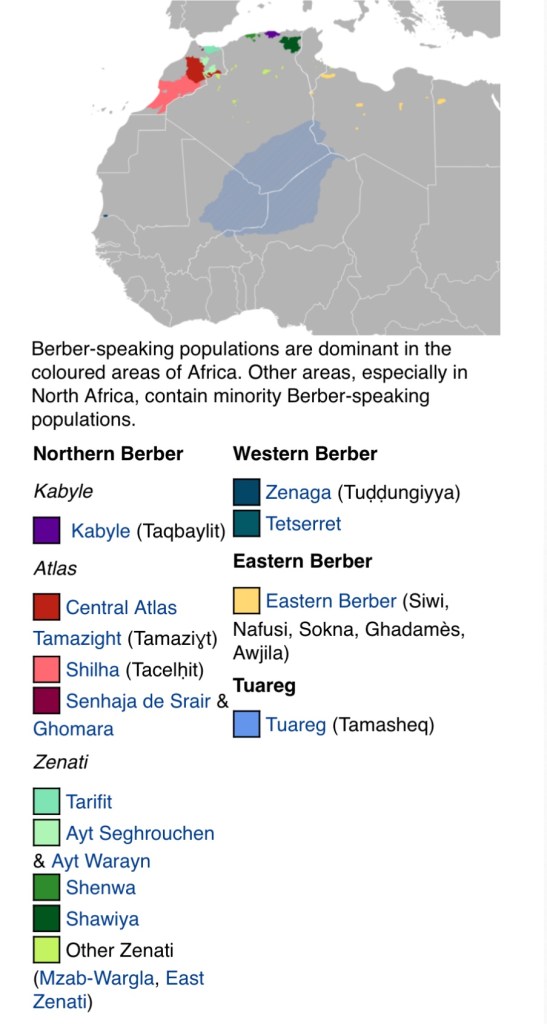

[Tamaziɣt language map]

As you can see from the linguistic map above, Siwi, the Tamaziɣt dialect spoken in Siwa, is clustered with several other variants under the subgroup of Eastern Berber. These other languages are likely more similar to what is spoken in Siwa, than say, the Tacelḥit spoken in western Morocco, but the paucity of Imazighen communities within this language group added to Siwa’s geographic isolation from all of the other Imazighen tribes has led it to develop a culture that is seperate, though not altogether singular, from both that of their Imazighen extended family and their Egyptian neighbors.

It is this Siwi Imazighen culture that the CMNH pop-up is attempting to highlight for museum guests, with pieces purchased over a decade in the 1970s and ‘80s by Professor Cassandra Vivian while teaching at the American University of Cairo and researching the lives of women living in Siwa and the other Egyptian oases. She donated these items to the museum, which were in turn curated Mina Milad, a Cairo-based artist and museum fellow, to try to best incapsulate unique aspects of Siwi life and how it may differ from what the public envisions as “Egyptian,” either past or present.

[Siwi fertility necklace]

One of the pieces Milad chose from Vivian’s collection was this aghaiz nesalhat, a fertility necklace made primarily out of silver, with beads of coral, glass, and acrylic resin. Like in broader ancient Egyptian culture, the fish depicted on the larger pendants are symbols of fertility, and unlike ancient Egypt (and modern Arabic culture), traditional Siwi jewelry favors silver over gold. Similar to several indigenous cultures in North America, Siwi women wear their silver jewelry both as a symbol of status and for spiritual protection. Because of its fertility powers, the aghaiz nesalhat, for example, is a necklace reserved for married women and one they will stop wearing when they wish to stop having children. Below is a picture from Wikipedia of the traditional necklace worn by unmarried Siwi girls made up of a large silver disk (adrim) and silver hoop (aghraw). This necklace appears to operate as a protective amulet, much like the bulla did for Roman boys, and like with how the bulla was ritually put aside when a boy reached the age to don the toga virilis, Siwi girls ceremonially surrender this necklace on their wedding day (perhaps to be replaced by an aghaiz nesalhat, if it can be afforded).

[Siwi adrim necklace]

[A gorgeous painting by Mina Milad of a Siwi woman in traditional bridal attire (2023)]

[The bride in the painting would wear elaborately woven and dyed slippers (zrabin) like these]

[A picture of a Siwi girl grinding salt, where you can see another instance of the traditional embroidery impressionistically represented in Milad’s painting. The heavily embroidered shawl both are wearing is called a tarfutet.]

Because Siwi women wear their wealth in their jewelry, one of the traditional wedding items is a woven basket (agnin en tankult) for their jewelry, presented by the groom. Part of the ceremony of the wedding night is him removing his bride’s jewelry, which if she comes from a wealthy family may weigh as much as thirteen pounds, so it’s just good sense to have somewhere to put all that. The jewelry basket in the pop-up is fairly small, so we can probably assume that it comes from a modest family.

[Agnin en tankult]

But all of this isn’t to say that the Siwi haven’t been touched by the various cultures that have come and gone in its land over the millennia. Throughout history, the steadiest outside cultural presence in the lives of the Siwi has been their nomadic Bedouin neighbors, who are also the only outside group that the Siwi will typically intermarry with, as both groups share many similar cultural values. Even then, relations between the local Awlad Ali Bedouin are established on a person to person basis, which in turn creates a bond between a specific pair of families, rather on a tribal level between the two groups. As we mentioned at the start, Siwa’s Egyptian temple of Amun was nearly as famous as the god’s cult centers in Karnak and Thebes, and when the Ptolemaic Greeks came through and synthesized Amun with Zeus, a second temple with Doric features was built in Siwa to Zeus-Ammon, which has records of use through the reign of the Roman emperor Trajan (2nd century CE). Cyrene’s large Jewish population were some of the earliest Christian converts and remained so deep into the 6th century, all the while maintaining their trade relationship with Siwa.

[A Siwi silver necklace made to hold a miniature Quran]

Following the birth of Islam and its conquest of Egypt, the Siwi became Muslims, but like many of the other Imazighen tribes, they have maintained some subtle traces of their preexisting syncretic religious culture alongside their unique sociological traditions—though many of these are threatened by the dominant Egyptian Arab culture they participate in, especially since the Egyptian government finally built an actual highway to connect Siwa with the rest of Egypt…in the 1980s…

[Before forty years ago, the only way to reach Siwa was by camel]

While perhaps not going so far as to say that the traditional Siwi were a matriarchy, women seemed to have enjoyed an elevated status in their early history that is generally more in line with older African cultures than Islmo-Arabic ones. Siwi marriage practices operate under the bride price system (groom pays bride’s family) as opposed to the dowry system (bride’s family pays groom/groom’s family), and much of a family’s tangible wealth is displayed in the jewelry of its female members. Perhaps because of this, Siwi women are typically the ones who control and manage a family’s finances, in addition to more patriarchy-aligned duties like child rearing. Like many indigenous cultures under threat, Siwi women, in their role as their children’s earliest teachers, are largely the ones preserving their native Tamaziɣt dialect into the modern era. Something that is all the more important as the Siwi community is only about 30,000 members strong (based on data from about ten years ago).

There is also evidence that traditional Siwi culture engaged in pederasty (intergenerational male same-sex relationships), many of which involved a separate form of marriage rite, but much of the information about these relationships is colored by the prejudices of the 19th century European anthropologists who first wrote about them, and later by the active suppression of the topic by not only the modern Egyptian government, but by the current tribal leadership which is more aligned with traditional Muslim attitudes towards homosexuality. Even contemporary Egyptian writers have not been allowed to included historical references to the practice in books printed as recently as 2005. From the flawed 19th century studies, it appears that the younger male partners were usually between the ages of twelve and eighteen, and while Siwi men under Islamic law could have four wives, these pederastic relationships were limited to a single partner and the relationship itself was strictly controlled by a community code. But we don’t know for certain the details of the same-sex marriage rites, nor do we know the intricacies of the code that governed these relationships, or how they were (presumably) terminated when the younger partner aged out of them (or if there were continuing obligations beyond the duration of the sexual relationship).

This is not to suggest that this is a practice that the Siwi or the Egyptian government should be encouraging out of a misplaced sense of cultural preservation. Children’s rights have (thankfully) advanced to the point that this should be as undesirable as opposite-sex child marriages. However, like child marriages (or slavery), pederasty was widely practiced in many cultures across the ancient world, and while we don’t condone it today, it largely concurred with the morality of its time. The problem is that most of the current opposition to discussing any of this is coming from an anti-homosexuality position, as opposed to a concern about protecting underage children from sexual predation. It is (obviously) ultimately the decision of the Siwi themselves how they wish to address this extinct practice, but in my opinion, erasure is rarely the best approach to difficult aspects of history, particularly when the motivations for doing so are shaded by our own present circumstances. Only time will tell how this plays out, though.

But there you have it, a brief introduction to some ancient but perhaps not-so-Egyptian Egyptians who in spite of millennia of extreme isolation managed to be at the crossroads of most of what we tend to describe as (ugh) “Western Civilization.” Blessed by at least five pantheons’ worth of gods over twelve thousand years, if any indigenous people are poised to survive our plasticine age of globalization, the Imazighen of Siwa are surely in the running for the top spot.

Leave a reply to All The Art We Do Not See: Curating From the Margins of the Art World – Sarah Holz Cancel reply