As promised, we’re back with round two on my latest experience in the Metropolitan Museum of Art—this week focused on the Greek and Roman Art wing. As my paraphrase of Ben Jonson above suggests, I spent more time with the Romans (and specifically the first century Romans of my books) than the Greek stuff, but as most of the Roman sculptures are Roman copies of original Greek pieces, I figure it evens out. Let’s see what caught my eye!

The center thoroughfare of this wing is home to the museum’s collection of Greek sculpture, or as we said, often more accurately, Roman copies of Greek originals. Here, the real delight was running into so many familiar friends whom we’ve talked about in previous posts about CMOA’s plaster cast collection.

Here, we find one of the so-called Wounded Amazons, one of a sculpture type usually delineated as a “Lansdowne” or “Sciarra.” The idea of five “types” of classical Amazon sculptures comes from a quote of Pliny the Elder describing five such Amazon bronzes in the great Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (Natural History, 34.75). The Sciarra type, of which the Met’s Lansdowne-style Roman marble copy above might be a subset, is thought to date from Tiberius’ reign (14-37 CE) and to be copying the work of the Greek artists Polyclitus or Kresilas (both active in the 5th century BCE). But as I alluded to last week and we’ll see moving forward, only parts of this statue are even the “original” Roman marble pieces. The Amazon’s lower legs and feet are also plaster casts taken from other versions of this piece in Berlin and Copenhagen, respectively.

And introducing another modern preservation/restoration technique beyond plaster casting, in the 18th and 19th centuries, master sculptors would produce marble pieces to complete broken classical sculptures. In this statue, most of the Amazon’s right arm, the lower part of the pillar she’s leaning on and, the plinth are such recreated pieces made in the 18th century. Proving once again that there’s no shame in reproductions in our dynamic museums of the future—those things have always been there, after all.

Another piece I recognized from a plaster cast I’d first seen at CMOA (shoved away in a dark corner, next to one of the lesser-used elevators), is this scene of Demeter and Persephone blessing Triptolemus, which is usually referred to as the Great Eleusinian Relief. In one version of the Persephone mythos, while searching for her abducted daughter, Demeter disguises herself as an old woman and agrees to serve the royal house of Eleusis after they show her hospitality. She becomes the nurse for Triptolemus and his younger brother, Demophon, and to repay the king and queen’s kindness, attempts to make the latter immortal by secretly placing him in a sacred fire at night. The queen discovers this by accident one night, and Demeter refuses to complete the ritual, but she promises to protect Eleusis if the city dedicates a cult to her, which becomes the famous Eleusinian Mysteries. Demeter teaches Triptolemus agriculture and he is thought to have been the first high priest of the Mysteries, hence his place in a sacred triad with the goddess and her daughter, representing the mystical bridge between the life-giving Demeter and Persephone, queen of the dead. Usually Demeter is identified as the goddess on the right, with her Olympian scepter and the gesture of giving something (likely a plant like wheat) to Triptolemus, symbolizing the gift of agriculture; with the leftmost goddess, with her Hecate torch and crowning gesture, as Persephone. However, arguments have been made in the reverse—likely driven by Demeter’s unmatronly loose hair.

The original Greek panel was found at Eleusis and is now in the National Archeological Museum in Athens; what the Met possesses here is ten marble fragments from a Roman copy of this relief made during Octavius’ reign in the 1st century BCE/CE. Aside from those fragments, this is nothing more than another plaster cast no different than the one at CMOA (except this one is afforded much better lighting).

Another familiar form, if not face, is this headless version of the Venus Genetrix figure, whose most famous copy was found in Fréjus and now lives in a much more complete form at the Louvre. Like that one, this is a marble Roman copy from the 1st or 2nd century CE of an original Greek bronze usually attributed to the sculpture Kallimachos (active late 5th century BCE).

As we’ve previously talked about, the “Genetrix” Venuses are generally denoted as such because the goddess is partially clothed, albeit scantily. Whether this was a conscious choice by the ruling Julio-Claudians, as a way to present their supposed ancestral goddess in a slightly less salacious manner is obviously debatable, but likely. Especially compared with the other major Aphrodite statue type copied by the Romans—the so-called Capitoline type typified by the Met’s version below, which is completely nude and sporting the suggestively disarrayed topknot hairstyle.

Before we move on to the Romans doing more Roman material, I wanted to pause on one more krater, in part because I found the apparent lack of consensus on its subject interesting. Found in Spina, Italy, this krater—a vessel designed for mixing wine in—is attributed to a group of 5th century (BCE) Greek painters working under the name of Polygnotos, the lead artisan of whom had in turn likely named himself after the famous fresco painter from Thasos of the same name. But the Met’s description of this piece merely says this is a “divine couple” being worshipped by ecstatic dancers, with no stab at which divine couple. At first, I just landed on the most obvious divine couple—Zeus and Hera, especially given the goddess’s impressive diadem, often one of the main ways to identify Hera, who is usually the most “queenly” goddess in appearance.

But I wasn’t really satisfied with the identification. I was bothered by the lion camped out on her arm (not an animal typically associated with Hera or Zeus), and the god’s odd, wiggly looking crown—not screaming Zeus, either. So, I moved on to the next most regal Greek divine couple: Hades and Persephone. When she’s depicted in her role as queen of the underworld, Persephone usually presents as a mirror of Hera, with a serious diadem and monarchical appearance; same for Hades as compared to Zeus. But again, neither of these two are particularly associated with lions; not to mention that neither of these couples’ worship would generally be considered “ecstatic,” though you could make an argument for the largely unknown Eleusinian Mysteries that Persephone was a part of as having an ecstatic component. Yet, if it isn’t these two, who’s left?

That’s when I realized that I was focusing on the wrong thing in this scene. Look at the figures on either side of the couple and at the god’s chiton—everything is spotted. You know, as if they were all wearing leopard skins…like the bacchae worshippers of Dionysus, who most certainly engage in ecstatic worship. Once you start thinking of Dionysus, everything else falls into place. While obviously more well known by his leopards, panthers and lions are also associated with the god; as are snakes, which are clearly what the god’s wiggly crown are supposed to be (if you look to the far left, you can see a maenad with a similar garland on her head). The mystery goddess becomes Ariadne in her divine form, Libera in Roman mythology, and her crown is to emphasize her transformation as well as her position as the wife of an immortal son of Zeus. While it is less common for the youthful and somewhat gender fluid Dionysus to be shown as bearded, it is not unheard of, as you can see below.

Anyway, I can’t prove that this is supposed to be Dionysus and Ariadne, but to me, it is the most likely explanation. If it not, I would argue that the seated couple are a mortal king and queen making a votive offering to the rather odd little figure standing on the altar to the right. Perhaps it is a sacred statue of Dionysus as a child; a sort of Dionysian version of Horus the Child/Harpokrates.

But after puzzling over that krater, I almost immediately stumbled into another mystery as I crossed the threshold into the purely Roman section of the wing. And it involves the head at the furthest left above.

This bust is of a similarly unidentified woman, but the Met’s description of this piece drew attention to her hairstyle, which is a particularly Ptolemaic style popular in Egypt and its dependent city-colony of Cyrene on the northeast coast of Libya. The description also noted that the person must have been important, as several copies of this portrait have survived. Well, stumbling on a mysterious, possibly Ptolemy-adjacent woman? Sign me up!

I do agree with the curators that no definitive answer springs to mind. This face doesn’t particularly match any of the Ptolemy queens or princesses I’m aware of from any part of the dynasty’s timeline. The nose is especially suspect, as most of the interbred Ptolemy women had ones that were larger or hooked, but it could be a match for two of Ptolemy VI’s daughters, Cleopatra Thea or Cleopatra III, who would fit the proposed possible timeframe of the 2nd century BCE for the original bust on which this on would be based.

Neither is a spot-on match, though. It also doesn’t appear to be a later portrait of the most famous pre-Cleopatra VII queen, the deified Arsinoë II, whose likely bust across the hall doesn’t look anything like this face.

I’ve seen portraits of Arsinoë II that could be said to resemble this mystery portrait’s nose, if only because Arsinoë has one of the few straight Ptolemy noses, but the unknown face is thinner and the cheekbones don’t seem to sit quite as high.

An alternative theory is that this was a portrait of one person, but Romans liked it and made it a portrait of another in the 1st century. The problem here becomes who would’ve been someone they liked enough to associate with this distinctively Egyptian hairstyle? No one we know who also resembles this face. Cleopatra’s nose goes through several iterations in her portraits, but the straightest version or portrait isn’t particularly similar to the unknown bust.

Nor does this portrait look very much like any we have of Cleopatra’s daughter, Cleopatra Selene II, whose face has very Ptolemy cheekbones and nose. But as I said, this could be someone else’s face used as a stand in for either of them. Cleopatra wasn’t exactly popular in the empire, but Selene was well thought of in the imperial family, so maybe it’s meant to be her.

My absolute most buck wild theory is, of course, that the dating is a little off and this is a portrait of my girl Arsinoë IV, who might have been paraded in front of the Romans in a distinctively Ptolemaic style to emphasize her position as a captured foreign queen; whose age would match this youthful portrait, and whose sympathy among the charmed Romans who defeated her might lead to interest in her face. Unlike the other Ptolemies we’ve mentioned, we have no surviving portraits of Arsinoë to compare against, and perhaps what faint similarities between this bust and the Cleopatra one mark siblinghood rather than artistic license.

Lastly, in a much less speculatively fun vein, it is possible that this was a Hellenistic portrait of an Egyptian goddess like Isis, and its popularity was for its association with her rather than a mortal woman. Though, one would assume some kind of marker or symbol to identify her, none of which are present beyond a Greek-Egyptian hairdo. Anyway, I know this has been me sleuthing with very little evidence at great length, but this was just such a striking face and I found it fascinating that we can’t figure out who it is. I promise we’ll settle down a little now.

To wrap up, I want to focus on Octavius and his people, mostly because the Met has a gallery largely dedicated to a fairly extensive reconstruction of one of the family villas in Boscotrecase, about two miles (3 km) northwest of Pompeii on the slopes of Mount Vesuvius. The house, built by Marcus Agrippa, was excavated in the early 20th century, with most of the artifacts and uncovered room sections removed and divided between the Met and the Archeological Museum in Naples. Work on the villa ceased when Vesuvius erupted again 1906 and reburied (and likely destroyed) anything else left of the structure or its contents. However, before its destruction, the excavation team had determined that this particular house had passed (at least until his banishment in 6 CE) into Agrippa’s son, Agrippa Postumus’ possession.

This bronze bust is really striking in person, and there is enough resemblance to Agrippa that I can believe it’s him, though it’s certainly the youngest and least world-weary portrait I’ve seen of him.

But that leaves open the possibility that this isn’t Agrippa, but rather one of the boys, his sons. Just as it looks almost too young to be Agrippa, it also looks too old to be Lucius Caesar; but it could possibly be Gaius or Postumus, who both lived a little longer.

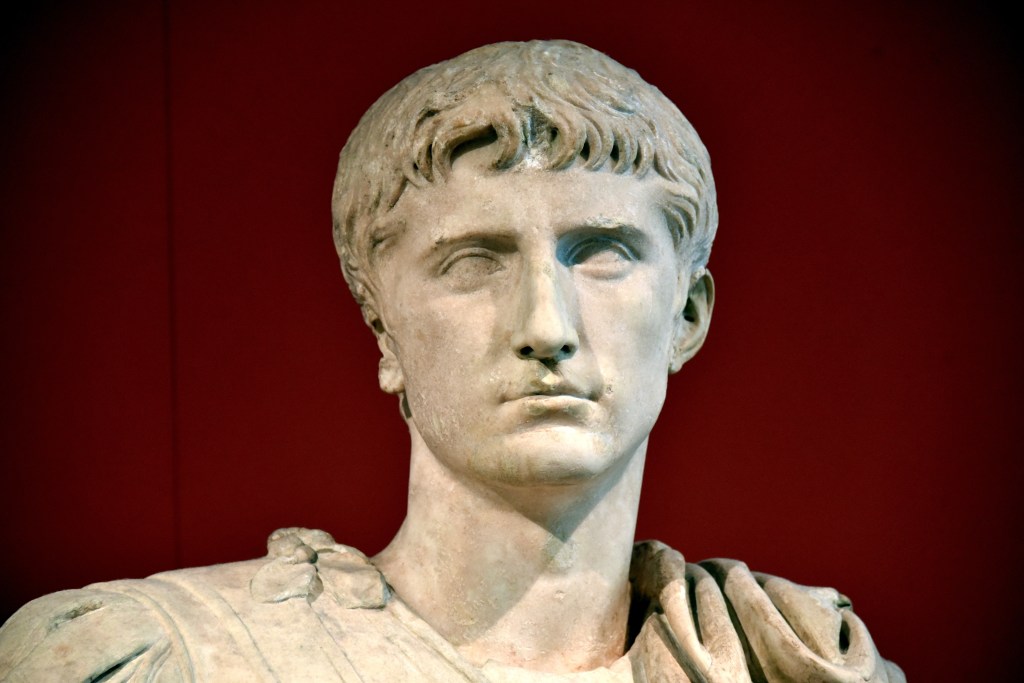

Compare the above bronze with this bust of Gaius and Postumus’ nephew, Gaius Germanicus (Caligula). Granted, this bust is one of Caligula’s more idealized portraits, meant to make him more closely resemble state portraits of Octavius to strengthen his ties to the imperium. In these smoothed out portraits, there is usually more archeological debate about whether a given depiction is of Caligula or his late Uncle Gaius, who almost invariably looks like portraits of a younger Octavius (see below).

What’s really nifty from Boscotrecase are the wall frescos, though. The Met has the full three-sided walls from a triclinium (dining room) and a cubiculum (bedroom) set up as rooms you can partially walk into, which gives you a good sense of color and scale for an upper class house.

While lovely and vibrant, I can’t say whether, as frescos owned by the imperial family, these are especially good paintings, but I enjoyed both seeing some of them in a simulacrum of verisimilitude, as well as the opportunity to look at home decorations many of my God’s Wife characters would have been intimately familiar with, which was neat.

Leave a comment