“[Saladin] gave [the stolen Christian baby] to the mother and she took it; with tears streaming down her face, and hugged the baby to her chest. The people were watching her and weeping and I was standing amongst them. She suckled it for some time and then Saladin ordered a horse to be fetched for her and she went back to camp.” – Bahā al-Din ibn Shaddād, The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin

To be objective

Applying myself to the ancient art

Of weighing history

But the imprint of old incense clinging

To these pages invites in

The romantic lord of endless honor

No one warned me

You were a trickster also, Yusuf

(poem from my research notes, 7/28/2021)

When I was nine, someone in my family gifted me a two-year subscription to the award-winning children’s literary magazine, Cricket—often dubbed “The New Yorker for Children.” Cricket, and its various age-appropriate satellite magazines, is a monthly publication of short stories, poems, and art, and I really can’t recommend it enough if you’re a parent with an elementary/middle school aged child who enjoys reading. I remember liking it a lot, but it’s truly incredible both what it exposed me to and what I find I have indelible literary memories of that I can trace back to its pages. Cricket was the first place I read (O, Muse) of the wrath of Achilles and the Trojan War; not to mention the first exposure I had to a lot of non-western folklore, especially from Asia. When I was reading Lady Hyegyeong’s memoirs in 2013 at the age of almost thirty, I was stopped dead in my tracks as she described a dream about a black dragon her father had had the night of her birth—because I recognized it from an adaptation of her story (“The Black Dragon Princess” by Hildi Kang) that I had read in Cricket in 1996.

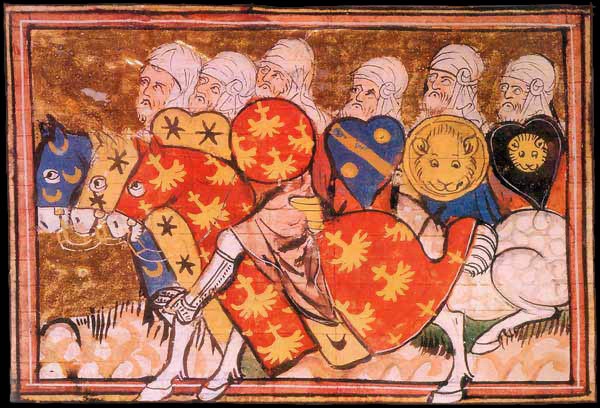

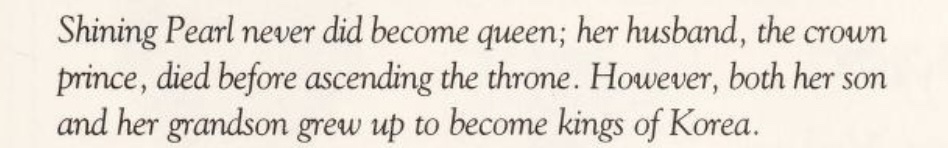

Cricket was also the first place I heard of Yusuf ibn Ayyub, better known to the western world as Saladin or Salah al-Din (ad-Din) (c. 1137-1193), the third major monarch featured in The Gourd and the Stars; and since we’ve already talked about Baldwin and Louis, it’s only fair we give him equal due. I met Salah al-Din in Eric Kimmel’s short story, “The Noblest Knight” (published in Cricket’s June 1995 edition), a simplified adaption of an English folktale likely based on the Old French poem Ordene de chevalerie (c. 1220). In Kimmel’s story, we meet Sir Hugh, a knight of modest means who is captured while fighting in medieval Palestine presumably during the Third Crusade. When Hugh is brought before Saladin, the sultan names a ransom price far beyond his ability to pay. Hugh explains this to Saladin, but says if the sultan will release him, he will go to his friends, ask them to help him raise the money, and return in thirty days with the ransom. Saladin’s emirs laugh at the proposal, thinking it is a trick, but Saladin releases him on the promise to return in thirty days with the money, with the understanding that if he returns without the ransom, the sultan will execute him. Hugh goes about to all of his friends in the Crusader camp attempting to raise the ransom money, but few of them will contribute, saying that he’s already free and his promise to an enemy doesn’t matter. Hugh chides them for this as being unbecoming of their chivalric oaths, but it doesn’t make much of a difference: when the time is up, he has managed to raise only a small fraction of his ransom. He sadly returns to Saladin’s camp and confesses the failure, prepared to die.

But Saladin is deeply moved by Hugh’s display of honor and declares to his emirs that it would be dishonorable of him to kill such a noble knight, willing to accept death to fulfill his promises, even to an enemy. Saladin passes around a bowl to his emirs, asking them to contribute to Hugh’s ransom, and when it has made it around the room, it is far more than the sum Hugh needed to raise. Saladin releases Hugh and offers to give him the money as a gift, but Hugh asks in return that he be allowed to use the money to ransom as many poorer soldiers held by the sultan as the amount will permit. The sultan is even more delighted by this show of selflessness, and releases all of the captives he has for nothing, along with letting Hugh leave with his “ransom.” The story concludes with Hugh in his old age, where the people back home point to him as the noblest knight; an accolade Hugh refuses to accept, saying that Saladin was in fact the noblest knight, as he had shown honor and generosity even when in a position to do what he wished to an enemy.

The original story in Ordene de chevalerie is a little more grounded in the mores of the twelfth century, with Hugh being Hugh II of Tiberias (stepson of Raymond of Tripoli for my readers), so a local Frankish baron rather than a European crusader. In the poem, Hugh, at Saladin’s request, instructs him in the tenets of knightly chivalry, but refuses to officially name him a knight because he says it would be a “wickedness” (L’Ordene de Chevalerie, Busby trans., p. 172) for him to perform the final requirement—that the ordaining knight, Hugh, strike the face of Saladin. The traditional blow was meant to remind the ordainee both of the valor of the knight who called him to knighthood and of the seriousness of the vows he had made, but Hugh believes that it would be wrong for him to take such a position over the sultan, both because of Saladin’s social standing as a king and as Hugh’s captor, who must needs have power over him. There is also some cultural subtext that, as a Muslim, Saladin can never truly be a full knight, hence the ordination never being completed. Despite this, Hugh asks Saladin to pay his ransom and here we have the intersection with the Kimmel story, with the sultan having his emirs collect the money, plus more for Hugh as a gift.

The poem itself is thought to have derived from a historical conflation of an incident in the late 1170s where Hugh was captured in a skirmish with Salah al-Din’s forces, but quickly released, combined with contemporary Frankish folklore about Humphrey II of Toron (1117-1179), lord constable of Jerusalem (head of the kingdom’s armies), whose prowess was such that the sultan was said to have desired to be knighted by him. Much in the way that the Continuations of William of Tyre, written by a bannerman of the House of Ibelin, elevates the prominence of that clan in its narrative, the anonymous L’Ordene was likely composed by a poet working in the orbit of Hugh of Tiberias and his European relatives in Saint-Omer, France, hence his position over the dead Humphrey of Toron in the story.

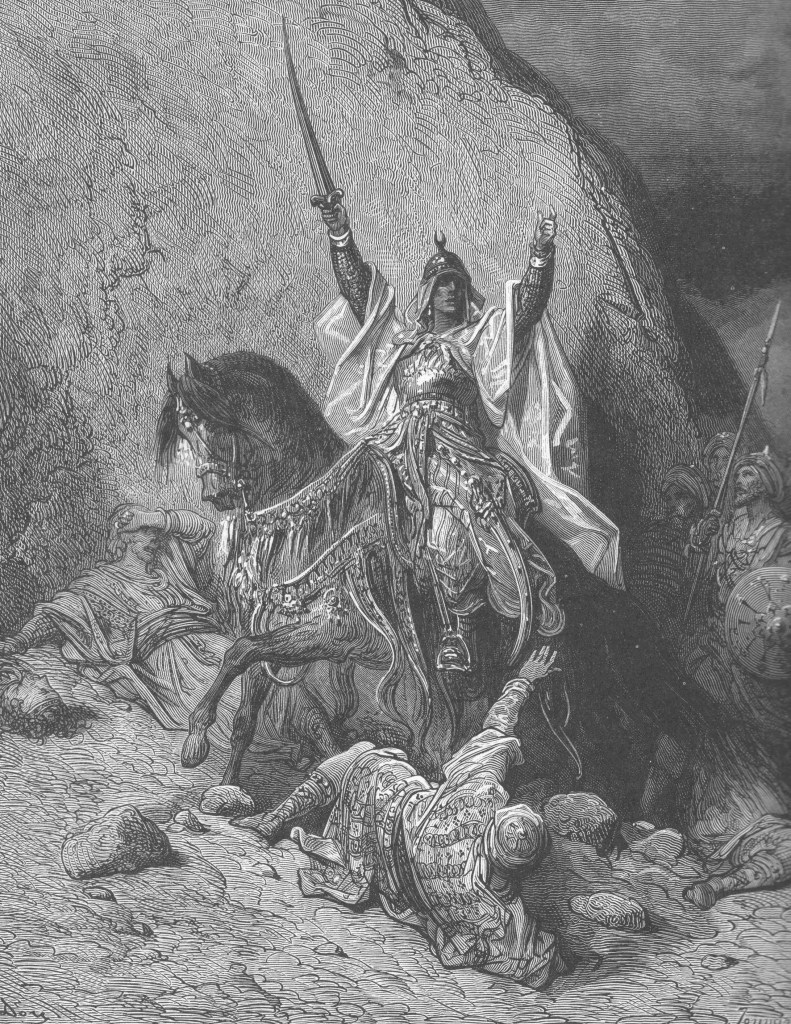

But both the more medieval L’Ordene and its modern reworking by Kimmel are very representative of an entire genre of stories that sprung up around Salah al-Din following his capture of Jerusalem in 1187 and the subsequent Third Crusade (1189-1192). You would expect medieval western literature (and the literary traditions that followed it) to turn the Muslim warlord who conquered most of the Holy Land and took its most revered city away from Christendom to be portrayed like a thirteenth century Osama bin Laden, but in fact, something much more interesting happened: rather than becoming an Antichrist, Salah al-Din became a hero of chivalric literature. Arguably one of the greatest heroes of the genre alongside Roland, Arthur, and Richard of England.

No other Islamic figure would be written of as much, or as positively, in the west as him—all the way up to the very moment you sit here reading this. This is doubly interesting considering that, until the Arab independence movements of the early twentieth century arrived and Pan-Arabinism needed a historical rallying point against western imperialism, Salah al-Din was a relatively minor figure in the Islamic world. And much like France looking at America’s fixation on the marquis de Lafayette, the Arab world was largely bemused by the European obsession with this one Muslim general and his short-lived dynasty for much of modern history. But there are several reasons for this, most of which are tied up in a curious confluence of Frankish religious and cultural traditions, and how they intersected with both Salah al-Din’s own culture and personality as we understand it from both European and Muslim sources. So I thought we’d take a gander at this and see if we can tease out how we all got here.

Briefly, Salah al-Din was born Yusuf ibn Ayyub in Tikrit, in modern-day Iraq, around 1137 to an ethnically Kurdish clan serving the interests of the Abbasid caliphate in medieval Baghdad under the military leadership of Nur al-Din Zengi (1118-1174). Nur al-Din, for the record, was for many centuries the “Saladin”-style hero in the Islamic world, in part because he experienced many decades of military victories against Frankish Palestine. Beneath the religious authority of the Abbasid caliphate, Nur al-Din served the temporal rule of the Zengid emirs who controlled the major cities of Damascus and Aleppo. During the early years of Salah al-Din’s life, the Islamic world of the medieval Middle East was fragmented into two caliphates—a Sunni Muslim one in Baghdad and a Shi’ite Muslim one in Cairo—and a constellation of semi-independent rival emirates and territories underneath them. These emirs and their vassal warlords and clans were in a near-constant state of conflict for land and resources with each other, and these interpersonal differences are a large part of why the First Crusade was able to take Jerusalem in the first place, as well as why the Latin kingdom of Jerusalem was able to exist for almost a century despite the relatively small number of men it had to defend its borders.

By the 1160s, the caliphate in Egypt, led by the Fatimid dynasty, was in serious decline and political control of it was almost exclusively in the hands of the hereditary caliphs’ viziers. In 1163, the vizier Shawar was ousted by a rival, and he turned to Nur al-Din, as the person with the strongest regional army, for help retaking Cairo. Nur al-Din agreed, sending Salah al-Din’s uncle, Asad ad-Din Shirkuh bin Shadhi, with a detachment to handle the matter and Salah al-Din accompanying him as his lieutenant. Shirkuh made quick work of Shawar’s rival, but in perhaps the least surprising turn of events imaginable, he also got rid of Shawar within a few years and established himself as the new Fatamid vizier on Nur al-Din’s behalf. But shortly after this, Shirkuh also died, and Salah al-Din took his place in 1169.

Any vestigial power the Fatimid caliph retained largely passed to Salah al-Din and he declared himself sultan of Egypt. He began consolidating power in the south, to the detriment of Nur al-Din’s control of the Arabian peninsula, which put him at odds with his ostensible boss, but Nur al-Din’s own death in 1174 stopped whatever opposition his forces would have mounted against him. Salah al-Din married Nur al-Din’s widow, Ismat ad-Din Khātūn (not her name, which we don’t know—“Khātūn” is a Turkic title equivalent to “Lady” and Ismat ad-Din, “purity of the Faith,” is a laqab) and began the work that would consume the next thirty years of his life: gaining control of as much of the Middle East as possible.

This involved defeating his rival emirs for control of Muslim cities like Damascus and Aleppo, as well as the more obvious task of driving out the Christian crusaders in Palestine. And despite attempts by his biographers like Imad ad-Din al-Isfahani and Bahā al-Din ibn Shaddād to emphasize Salah al-Din’s piety and zeal for getting rid of the Franks, the fact remains that during those nearly three decades, Salah al-Din spent a great deal more time killing fellow Muslims than he did scourging the infidel. Like the Franks’ own position in the Latin Middle East, religiosity was important, but never at the expense of common sense.

As a result, if it benefited Salah al-Din to make temporary truces and concessions to Baldwin, and later (briefly) Guy de Lusignan and the kings of the Third Crusade, so he could focus on his Zengi rivals in Aleppo or cashing out the Bedouin clans, he did, regardless of religion. This sort of give and take between Muslim generals and the kingdom of Jerusalem had been going on for a century, so it would have been no surprise to a “native” like Baldwin, but it was likely a revelation to the lords who came over to Palestine with Richard and Philip, who had been primed to find literally Satan Himself waiting for them. Instead, they found a brave and intelligent ruler who, aside from the matter of religion, was very recognizable to them from a sociological perspective. Medieval Islamic honor culture would have been similar to European chivalric codes of the time, and Salah al-Din bore the same hallmarks that any good Christian ruler would have: military valor; generosity; respect for social hierarchies; and a commitment to justice and, where appropriate, clemency. Seeing themselves so perfectly mirrored in the Other clearly had a profound effect on the crusaders who encountered him and they brought those impressions home with them, where they germinated into the mythos of an enemy so noble that he could almost be a Christian knight. Indeed, it was a popular folk belief in Europe that Salah al-Din converted to Christianity on his deathbed—so that he could be entirely absorbed into the proper circle of chivalric tradition.

Also, the figure of Salah al-Din posed a profound religious paradox in a Christian society that viewed everything as the result of divine revelation, one similar to the paradox of the conquest of Antioch during the First Crusade that we touched on briefly in my entry about the crusade poem Richard Coer de Lyon. There, Christians had to reconcile the terrible circumstances of the siege of the city (the mass starvation, the alleged cannibalism) with the crusaders’ ultimate victory (did that mean that God approved of the cannibalism?). With Salah al-Din, Christendom had to reconcile his victory and the loss of Jerusalem in a concurrent paradigm. While it was possible to frame the sultan as merely an instrument of divine punishment for Christian sin, theologically speaking, it wasn’t entirely out of the realm of possibility that there was more to it than that. The possibility that God had given Jerusalem to Salah al-Din, that God had judged him somehow worthier than Christendom and had chosen him to rule His city—and what did that mean? Particularly when it became clear that Jerusalem would not be quickly retaken by any Frankish forces. Literarily acknowledging and celebrating the sultan’s “Christian” qualities might have also been a cultural psychological coping mechanism to explain these events in a way that made sense to the people who experienced them.

I confess that when I set out to write The Gourd and the Stars, I told myself that I wouldn’t be seduced by this tradition. No matter how much I’d clearly loved “The Noblest Knight” as a child, no matter how much I had enjoyed Ghassan Massoud’s performance in Kingdom of Heaven, I was going to maintain some objectivity when it came to creating my Salah al-Din. But as the personal poem I included in my flavor text and the ultimate result of my novel attests, I don’t think I was very successful. However, like apparently many of the medieval people who encountered him in his own time, I don’t really rue my failure. I loved writing the Salah al-Din who exists in my books, and if he is just another refraction in a very large and long-standing literary mirror, there are certainly worse fates to suffer as an author.

Leave a comment