“Even beauty changed. You changed. You were caught in the midst of complex currents of continual change. Perhaps it was good, if only you could accept it completely—if only your heartstrings would accept it. Perhaps it could keep you alive and happy and excited, if you knew how to use it. That was how you revolved in harmony with the world, instead of trying to buck it, to alter its direction according to yours.” (Lost Island, p.241)

“Anderson and I commune continually; we nibble delicately at the earth as though it were a piece of cheese, and we fool with stars as though they were a handful of beads.” Barbara Follett, December 1930 (Barbara Newhall Follett: A Life in Letters, p.494)

“‘What worries me,’ Jane said, ‘is that I’m afraid it’s coming to an end, and not a particularly happy one.’” (Lost Island, p.184)

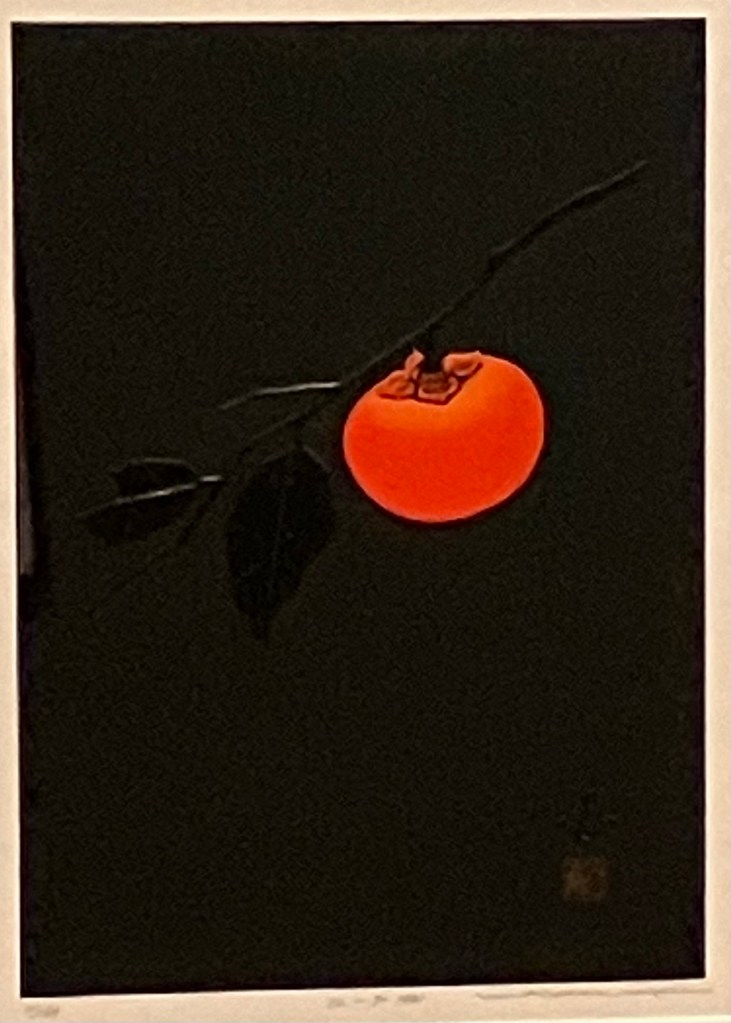

I had planned to do another museum entry about the briefly aforementioned Titanic exhibit over at the Science Center and the last round of prints in CMOA’s Japanese shin-hanga and sōsaku-hanga exhibition, but I confess that I didn’t unearth enough of a thread on either to justify a whole post. So here are some highlights:

Over across the city at the science center, the Titanic exhibition was similar to ones that have been touring for years (or the one on semi-permanent display at Luxor in Las Vegas), so if you’ve seen a recreated first class stateroom and recovered glassware, this one doesn’t bring a whole lot new to the table. But my inner twelve year old still likes Titanic stuff, and there was the part where the murky lighting around the section with the ice warnings and the crash made my phone camera freak out and makes my photos look as though they were possessed by angry ship ghosts.

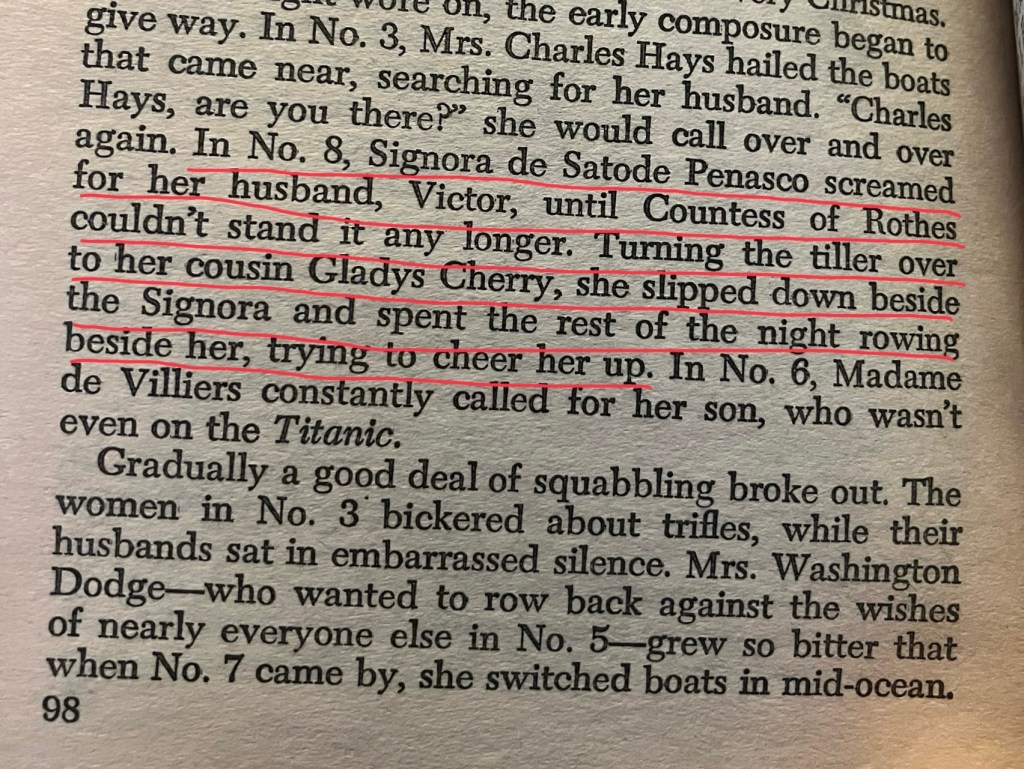

Not to mention the exhibition reeled me in the same way my seventh grade teacher, Mrs. Murphy, did when we were reading Walter Lord’s A Night to Remember—they assigned me a passenger doppelgänger. And I’m a sucker for that kind of stuff. In an upgrade from Mrs. Murphy’s class, where I drew third class traveler Katherine Mullins, this time I got first class passenger Maria Josefa Perez de Soto y Vallejo de Satode Peñasco y Castellana.

But, like with Kate Mullins, that means I am also 2/2 on drawing survivors rather than victims of the disaster. At the end of the exhibition, there was a QR scanner that you ran your ticket through to find out your passenger’s fate. As I already revealed, Maria did survive. Anyway, it was an interesting way to make the whole thing more interactive (that and touching “an iceberg”).

But when I wasn’t at the museum last week, I was with another shipwreck and another old friend of the blog, Barbara Newhall Follett. Last time, we discussed her preteen novel, The House Without Windows, but I had recently acquired a copy of her only surviving adult work, Lost Island. An unpublished novella manuscript at the time of her mysterious disappearance in 1939, it was published in 2018 under the direction of Follett’s surviving relatives, namely Stefan Cooke (somewhat awkwardly, a grandson of Barbara’s father’s despised second family that he left hers for). But complicated family dynamics aside, I wanted to see where Follett as a more mature writer was at the end (?) of her life, and how it compared to THWW. In particular, comparing that childhood story to a later work, and seeing if the way readers have tended to see Follett as an autobiographical author continues to be justified in Lost Island.

The short answer is emphatically yes. Reading Lost Island on top of THWW, and Cooke’s published volume of Follett’s letters, it is impossible not to continue to see Barbara’s subsequent life in her writing. Not that that’s a bad thing—and veiled autobiographical fiction was very au courant in the late 1930s/early 1940s (think Hemingway, Steinbeck, and later, Kerouac).

As I touched on very briefly toward the end of the post about THWW, Follett’s later teens and young adulthood after her father left the family for another relationship were difficult emotionally and financially for her and her mother. To make ends meet, they worked various secretarial jobs in New York City, as well as tried to fall back on their shared writing background to publish articles in newspapers and magazines. One of their schemes on this front led to them spending several years traveling in the Caribbean and South Pacific so they could write travelogues that they could later sell for publication.

Neither of them produced anything that sold, and despite the relatively cheapness of their travels, money was a constant problem. Barbara and her mother clashed over everything, but especially over Barbara’s behavior, which was considered delinquent. When they returned to California, Barbara periodically ran away from both of her increasingly estranged parents, while trying to be emancipated from the control of either. One of these times included her spending some time in juvenile detention as a runaway while her parents argued about whose fault Barbara was.

She also became deeply emotionally involved with Ed Anderson, a sailor who’d she met during their Pacific adventures. What probably began with Follett’s continued general interest in sailing and ship life from her years writing her second childhood novel, The Voyage of the Norman D, became a serious attachment to Anderson. Follett’s copious letters to him (usually referred to as “A.” to her friends), show a genuine reciprocal friendship and romantic affection between her and the older seaman (Anderson was at least in his mid/late twenties; Barbara was only fifteen when they met). But after several years of trying to make any kind of relationship between them work, Follett eventually broke off the connection. This was due to a variety of factors, but the main one was financial: Anderson, as a sailor, was constantly away chasing work, and Barbara had to do the same with odd office jobs in either Los Angeles or New York, far from Anderson’s Seattle. Barbara had, by 1931, also met her future husband, Nick Rodgers, and while (based on her surviving correspondence) she was perhaps not as spiritually connected with Nick as she’d been with Anderson, he was able to be more physically present in her life and at least appeared to offer her more stability. Though, based on the later disintegration of their marriage and then Follett’s disappearance, one wonders if she would have been better off with Anderson.

Anyway, Follett weaves many of these threads into Lost Island. At least initially, LI is a much more realistic novel than the fabulist House Without Windows. Our protagonist, Jane, is an unassuming young woman working as a secretary in New York City and generally living a life typical of the newish class of working girls in the city at the time, complete with roommates and friends equally grinding (the Depression is never specifically mentioned, but there are numerous allusions to jobs being “hard to come by”). Yearning for adventure and the wilderness of the Maine woods of her childhood, after work one day Jane stumbles upon an old fashioned schooner, the Annie Marlow, docked outside the city. In a fit of terminal YOLO, she talks herself onto the ship for its next voyage as a passenger (even though it’s a lumber vessel).

Aside from a mildly disapproving first mate, the crew of the Annie Marlow quickly accept Jane’s presence, and she delights so much in being at sea that it’s played for laughs that it takes her weeks into the voyage to even ask where they’re going (Valparaíso). In particular, she forms a close bond with the ship’s studious second mate, Davidson (or Daveson—the only lightly corrected MS can’t quite make up its mind which it is). They share a love reading, especially the works of Joseph Conrad (which suggests Follett means the “Marlow” in the ship’s name to be a Heart of Darkness reference), and have quiet, philosophically-inclined conversations about life. The captain worries a bit that they’ve formed a romantic attachment, but Jane assures him it is solely platonic. But Jane’s nautical idyll is shattered by a storm that wrecks the Annie Marlow and leaves her and Davidson as the sole survivors. After a harrowing, unspecified amount of time adrift at sea with dwindling provisions, they wash ashore on an unknown tropical island.

Now, as a kid who grew up with Island of the Blue Dolphins and Hatchet, I was primed for a bootstrapping survival story, but our characters’ arrival on the titular Lost Island is where Follett’s naturalistic whimsy enters her otherwise relatively realistic plot. The Lost Island is an Edenistic paradise with plenty of food and fresh water, both of which are obtained with minimal effort. There are no serious predators, and the weather is almost uniformly favorable. Jane and Davidson easily abandon their (admittedly already dubious) interest in the “civilized” world they’ve lost as easily as they abandon their clothes. Of course, this is where their totally platonic friendship becomes a romantic sexual one, but both are blissfully content to remain castaways for the rest of their lives.

Three years later, though, a geological survey team stumbles on the island and discovers them. Jane’s instinct is to refuse their offer to take them back to New York, but Davidson, having that sailor blood in him, wavers at the thought of returning to a seafaring life. As it turns out, they don’t really end up having a choice because the survey team finds gold on the island, so there isn’t any way they could stay in the lives they’d been living. Once they are back in New York, they try to hold onto the magic of the island and their relationship, but Davidson can’t find work and refuses to stay if he can’t provide for Jane, so eventually they agree to go their separate ways. Jane flirts for a while with an old friend who loves the woods and takes her dancing, but ends up breaking things off with him too. When we leave her, she’s almost right back where started—living single and working in the city—but the story ends on a tenuous note that having escaped that world once before, Jane might be capable of doing it again.

Even from this brief synopsis and even briefer sketch I made of Follett’s real life experiences, the parallels are pretty obvious. Jane is the author insert and Davidson clearly based on Ed Anderson; even Nick Rogers makes an appearance as John, Jane’s more worldly second suitor, complete with Barbara’s growing ambivalence toward him. Aside from the magic of the Lost Island, Follett’s fantasies are much more mundane than the Peter Pan-esque flights of Eepersip in THWW: Jane has a steady, if dull, job that pays enough to get by on (something Follett herself always struggled with as an adult) and one she gets back with no trouble despite being marooned for three years; Jane’s troublesome, tyrannical father is someone she chose to leave (as opposed to Follett’s father, who left her); the break between Davidson and Jane is his choice (not the one that Follett chose to make with Anderson). Even the magic of the island feels feverish and unreal, as if Follett can’t quite let herself dream that big anymore.

Follett’s dialogue is pretty pedestrian and of-its-time (the way she writes dialogue is very similar to how she talks in her letters), but as I think the quotes I use in my flavor text above show that her early promise in THWW of beautiful writing comes crashing through her sometimes otherwise mundane prose in LI.

And because there’s so much of Follett in this book (and all her writing) and she’s such an original, one might be tempted to think that Lost Island is a strange, lonely little artifact floating along in the sea of literature. But, perhaps ironically, there are at least two works I can think of that remind me of it that I’ve talked about right here, and those are Daphnis and Chloe and Urania. The pastoralism of both of those novels, and especially D&C for the innocent sensuality of Jane and Davidson, was particularly striking to me. But since they can’t return to the country (island) as the Greek lovers can, they also can’t have Daphnis and Chloe’s happy ending. And it’s that melancholy for a lost happiness and an authorial inability to recapture it even in fiction (as well as the intensity of the roman à clef elements) that reminded me so strongly of Mary Wroth and Urania. Proving that unlike the Lost Island, no writer is ever truly an island from what has come before them.

But Follett has one more trick up her own sleeve, and that’s that she ends Lost Island with almost the same tantalizing note that she did with THWW. There, Eepersip escapes to become a nymph of the air; here, Follett hints that Jane may yet escape the doom of civilization that brought her back to the city:

“Jane laughed again, but there was a gleam of danger in her eye. Sometime, not too far off, she would stage another rebellion. It would not be the same kind of rebellion, though. One could never repeat the real adventures. That was why so many people were unhappy, she reflected. They tried to go back and repeat the things that had made them happy before. They tried to retrace the trail and visit again the places where they had known their highest ecstasies; whereas, if only they had the courage to push on, forward, over deserts and swamps and glaciers, they would sometimes make new discoveries as bright as the others, or even brighter, perhaps….One good way to start a rebellion was to buy a red, red skirt….”

(LI, p.246)

With another literary wink like that, is it any wonder readers keep looking for Follett’s missing footprints in the snow so long after she vanished?

Leave a comment