“Ma spread the between-meals red-checked cloth on the table, and on it she set the shining-clean lamp. She laid there the paper-covered Bible, the big green Wonders of the Animal World, and the novel named Millbank.” – On the Banks of Plum Creek, chapter 17

“Every window and shutter at Millbank was closed. Knots of crape were streaming from the bell-knobs, and all around the house there was that deep hush which only the presence of death can inspire. Indoors there was a kind of twilight gloom pervading the rooms, and the servants spoke in whispers whenever they came near the chamber where the old squire lay in his handsome coffin, waiting the arrival of Roger, who had been in St. Louis when his father died, and who was expected home on the night when our story opens.” – Millbank, chapter one

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania has long been (in)famous for its idiosyncratic local dialect, usually colloquially coined as Yinzer (derived from the dialect’s propensity to express “you” as “yinz”, as in, “Yinz all gawn’ dawn to the Stillers’ game?”). Despite it consistently ranking next to South Bostonian as one of the United States’ least attractive accents, as a transplant to the region, I’ve always had a soft spot for it—in part because it is so distinctive. Which is a shame because like many regional accents, Yinzer is experiencing the linguistic homogenization that comes from a century of exposure to long-distance national media (radio, television, cinema, and lately, social media), and as a result, its most emphatic iterations will likely die out with the passing of the Western Pennsylvanian Boomer generation.

Aside from its instantly recognizable accent, Yinzer also has a treasure trove of regional vocabulary that, as a word-curious person, has always fascinated and delighted me. Many of these words, like “gum band” for a rubber band, have long passed out of common parlance, but some continue to have staying power as they are adopted by newcomers such as myself. Anyway, all of this is a long way of introducing the non-initiated to one of my favorites: nebby, which means being (perhaps overly) curious or interested in the goings-on of others. I’m guessing it derives from the archaic Anglo-Scots use of neb for alternately a bird’s beak or a person’s mouth—which perfectly suits the nosy-neighbor connotation of “nebby” in Yinzer. Like many Yinzer-specific words and phrases (“jagoff” comes to mind…), nebby has softened somewhat in its linguistic drift and is more likely to be less pointed in meaning than it used to be. I tend to use it in what is probably a much more fond way than its original speakers did—I think of myself as a curious little sparrow hopping over to be nebby about something, as opposed to being a heron squawking and jabbing its enormous beak into a situation.

All of this was preamble so I could start this entry off by telling you that the only thing I am nebbier about than what other people are reading in the real world is learning what my favorite fictional characters are reading. Name-dropping other books in works of fiction always interests me because of what it might tell you about the author as well as the personality or inclinations of the characters. Readers of my books know I love to insert writers as characters in my novels, and in the case of my God’s Wife guys, name drop them elsewhere. Part of that I’ll admit is just me skipping around throwing Easter eggs in, but it does serve a genuine plot purpose as well—because I think many modern readers can’t grasp how important and relevant the classical writers were to western education and culture until very recently. My non-GW characters reading Ovid and quoting Virgil is me having fun, but it’s also a shorthand their contemporaries would recognize as both grounding them in their times and laying out the sort of educational exposure they have.

In short, if a story tells me this character is reading X, if I’m not familiar with X, I’m interested in seeking it out to better understand the character, and possibly the author. Sometimes this leads to truly catastrophic situations, like when you force yourself to read The Pilgrim’s Progress because the March girls love it so much and Louisa May Alcott structures many of Little Women’s chapters around imagery from Bunyan’s work.

So, yeah, in 1864 Boston, I don’t think the Marches had any excuse to be reading something so awful (I also read The Pickwick Papers for these girls, and while miles better than Bunyan, it’s nowhere near my favorite Dickens). But mid/late 19th century America was decidedly a place where literary access varied wildly depending on where you were, and what happened for women who didn’t live in a major metropolitan area? What were they reading while the March sisters “played Pilgrims”? Well, an interesting window on this question opens up in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House series. In the Little House books, education, schools, and the written word are held in a rarified space—in part because in the American Western narratives of the mid/late 19th century, these would have been coded as civilized, feminine aspects of life in the otherwise masculine space of “The West.” And because the Little House books are framed from the quasi-fictional Laura’s perspective, there is a constant tension between Laura’s internal femininity and the outer masculinity of her environment. Professor Ann Romines lays this tension out in great detail in her book, Constructing the Little House: Gender, Culture, and Laura Ingalls Wilder (U. of Massachusetts Press, 1997), showing how it is personified in the narrative by Laura’s parents, Charles and Caroline Ingalls.

In the early books, spunky Laura is more attracted to the masculine-coded world represented by her father—the moving ever-westward, the wildness of the environment, the more proactive aspects of living outside of white American Victorian culture—but a lot of her character arc as she moves from childhood to adulthood through the narrative is low key her coming to grips with her femininity, represented by her mother. While there is understandable reader angst watching free-spirited Laura give up much of her prairie wildness as the series brings her to town life, work, and traditional marriage—I don’t think it is necessarily an angst Laura the author shared. Or rather, unlike her more iconoclastic daughter, I think Wilder viewed this as an inevitable conclusion. Not just because it was ostensibly what actually happened to her, but because that was just the way things generally were for women of her generation everywhere. The later books still demonstrate the same adoration of her father, but they also show character Laura moving closer to the mother she sometimes butted heads with as a girl. In contrast to the impulsive, laughter-filled, fiddle-playing Pa Ingalls, the serious, sensible, do-your-chores-and-say-your-prayers Ma is not usually a fan favorite character. And although her period-appropriate levels of racism and internalized misogyny aren’t exactly winning traits either, something that coming back to this series as an adult has really highlighted for me is just how much Caroline is the character holding together the whole pioneer circus her husband is hellbent on chasing.

White pioneer women, both in fiction and real life, were the torchbearers, for better or worse, of Victorian Anglo-Saxon culture and values into the “untamed wilderness” of the American West. Women were the ones holding the family together through travel and homesteading, often alone as men followed seasonal employment and made the long journeys to the nearest population center to trade for goods that couldn’t be manufactured at home—and Caroline Ingalls, both as a real and fictional person, is a paradigm of her era. Aside from all of the times she’s left alone with 2-4 small children in the middle of nowhere to figure things out while her husband tries to fix the latest jam his schemes have landed them in, Caroline is consistently portrayed as more educated and from a (marginally) more affluent background than Charles. The books typify this by mentioning how Ma taught school before her marriage and previously owned dresses made by a seamstress rather than the ones she makes herself throughout the narrative (Little House in the Big Woods, chapter 7). As the books progress, Ma is the one who tethers her pioneer family to the world beyond their various “little houses.” She’s the one who writes letters to far-flung relatives to maintain some semblance of extended kinship network for her daughters, and she’s the one who educates them when they don’t have access to schools. And it is Ma who is the driving force behind the family’s eventual settling in De Smet, South Dakota (the titular “Little Town on the Prairie”), finally putting her foot down not to move again when her oldest daughters are teenagers.

Despite her affinity for reading and education, according to the Little House, the Ingallses don’t own many books. Like most American households of the time, they owned a Bible—crucial for a family who was often too far away from a church to practice religion any other way besides reading from scripture on Sundays. But the only other consistently mentioned reading materials outside of the occasional access to women’s monthly periodicals of the time like Godey’s Lady’s Book are the two books mentioned in my flavor text: an illustrated work called Wonders of the Animal World, and the 1871 novel Millbank, by American author Mary Jane Holmes. First mentioned by name in this passage from On the Banks of Plum Creek, Millbank is “Ma’s book,” and in an unused, early draft of Little House in the Big Woods, Wilder describes Caroline’s brother, Thomas Quiner, as the one who gives it to her during a visit (Romines, 265-6; n.16). And although this draft calls the book “not for little girls” (ibid), Wilder also remembered Caroline reading it aloud so many times that she knew the opening lines (quoted above my other flavor text) by heart before she was able to read (Romines, 14).

Some of this hyperfixation was undoubtedly for sentimental reasons—a reminder of her brother and family back east—not to mention it was almost literally the only book they had to pass the time with. But aside from this, Millbank must have had some deeper hold over Caroline Ingalls to cause her to put aside any moralistic doubts over reading an adult book to her children and expose them to it so repeatedly and so young. So I thought we’d use the rest of our time to take a brief look at Mary Holmes generally and Millbank specifically, and see if we can tease out any speculative answers about that.

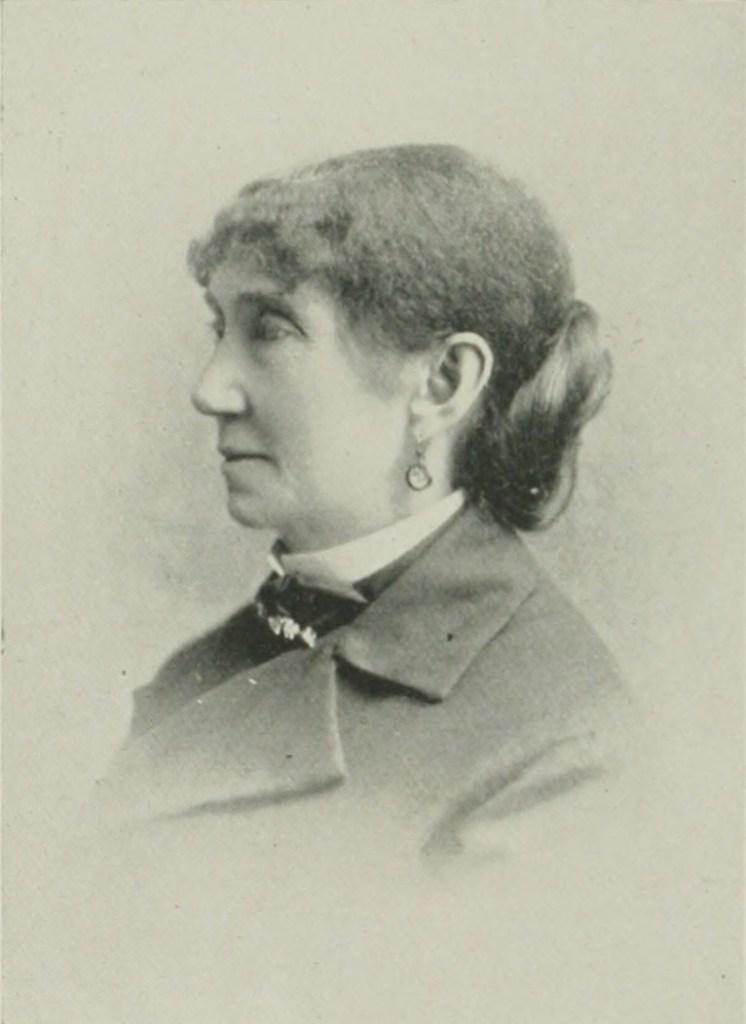

Mary Jane Holmes (1825-1907) was the remarkably prolific author of nearly forty novels and short stories, the first of which was published when she was only fifteen. Like many of the pejoratively-named “sentimental novelists” of the 19th century, most of whom were women, Holmes’ oeuvre has largely fallen by the literary wayside, but she sold over two million copies of her books just in her lifetime, a figure that puts her second only to Harriet Beecher Stowe in the era. Part of her appeal to female readers like the Ingalls women was Holmes’ focus on women characters and their concerns within the confines of rural and small town America—another reason she and her fellow women novelists were often overlooked by the male literary establishment. But much like Stowe, Holmes was deeply interested in contemporary social issues and her deceptively simple novels often dealt with serious issues such as class, race, and gender dynamics.

Born in Massachusetts, Holmes would spend a few years of her early married life teaching with husband Daniel in rural Kentucky, which would give her fodder for her novels set in the American South. But the vast majority of her adult life would be spent in Brockport, New York (about twenty miles west of Rochester). There, she would write her first novel, Tempest and Sunshine, and her husband would practice law. While the characters and stories in her novels aren’t exactly radical, generally speaking, Holmes herself led what was a fairly atypical life for a woman of her time and class. She and her husband remained childfree, they traveled extensively internationally, and they reportedly enjoyed a co-equal, professionally supportive relationship, which Mary modeled many of the relationships in her stories on. Indeed, it’s this streak of independence that filters into Holmes’ female protagonists, who usually have to overcome adversity by going out into the world and gaining some measure of experience and self-sufficiency before they can return to the supposedly desired domestic sphere as wives and mothers.

Millbank is no exception to these authorial tropes. Like many 19th century novels, it has an extra title clause, and its full title is Millbank; or, Roger Irving’s Ward. The secondary title is actually more instructive toward pointing the reader to where their attention should be, as the titular ward is Magdalen, the primary female protagonist of the story. Abandoned by her mother on a train into the hands of teenaged Roger Irving, the heir of the titular house, Millbank, Magdalen grows up alongside her young father-figure, Roger, and Frank, the son of Roger’s older, deceased half-brother—but obviously the situation quickly escalates into a love triangle between the three of them. Behind this romantic subplot are two quasi-Gothic ones about competing wills (as in, last testaments) over which man is the rightful heir of Millbank, and Magdalen’s true parentage. Given Roger’s nigh-saintliness and Frank’s well-meaning fecklessness, Magdalen’s ultimate choice is telegraphed from the start, but to reach her happy ending, she and Roger have to lose everything first and work their way back to one another (think like Jane Eyre having to leave Rochester and Thornfield, and earn her independence before she can return to them).

But just like many modern fictional love triangles aimed at a female readership, Holmes goes through great pains to not paint Frank, for all his faults, as a villain, even though he’s a narrative impediment to Magdalen’s relationship with Roger. The real villains of Millbank are upper class women—Frank’s mother, Helen, who spends most of the novel scheming to disinherit Roger so that Frank (and her) gets his grandfather’s vast fortune; and to a lesser extent, the heartless women of Magdalen’s father’s family, who essentially drive her mother insane with their denigration of her inferior class status. Although he is extremely wealthy for much of the novel, Roger is shown to be industrious and resourceful; able to work for himself when he loses his inheritance, unlike Frank who squanders everything almost the moment it’s his. Magdalen, too, shares Roger’s work ethic; rather than relying on Roger or Frank when the catastrophe of the wills comes to a head, she finds herself a respectable position for her class and education as a lady’s companion. The novel rewards her pluck by having her employment situation lead to the resolution of the mystery of her origins, by which she “earns” the financial independence that will allow her to rescue Millbank from auction and allow her to enter her marriage to Roger as his equal (again, much like Jane Eyre).

And I think these are the elements that appealed to readers like the far-flung Ingalls women. Sure, the spicer bits like the wish-fulfillment of having basically infinite money for clothes, luxuries, and opportunities; the romantic love triangle; and the Gothic mystery elements of hidden wills, lost mothers, and secret families are enticing on their own. But I think what (even subconsciously) was really speaking to particularly Caroline Ingalls was Millbank’s deeper morality and messaging. Its championing of hard work and thrift irrespective of personal wealth; its disdain for the idle rich and their vices, particularly gambling and seduction; the idea that even women can make their way in the world if they are courageous and ingenious; the importance of forgiveness and, as Dom Toretto would say, of family. These are all values Ma would try to instill in her daughters and ones that Laura Wilder would infuse her Little House books with through memories of her mother. Her overt literary legacy may be as veiled as that of her heroine’s parentage, but Mary Holmes’ influence on the next generation of American women writers is, like Magdalen’s lost mother, waiting to be rediscovered by any of us willing to go out and find it.

Leave a comment