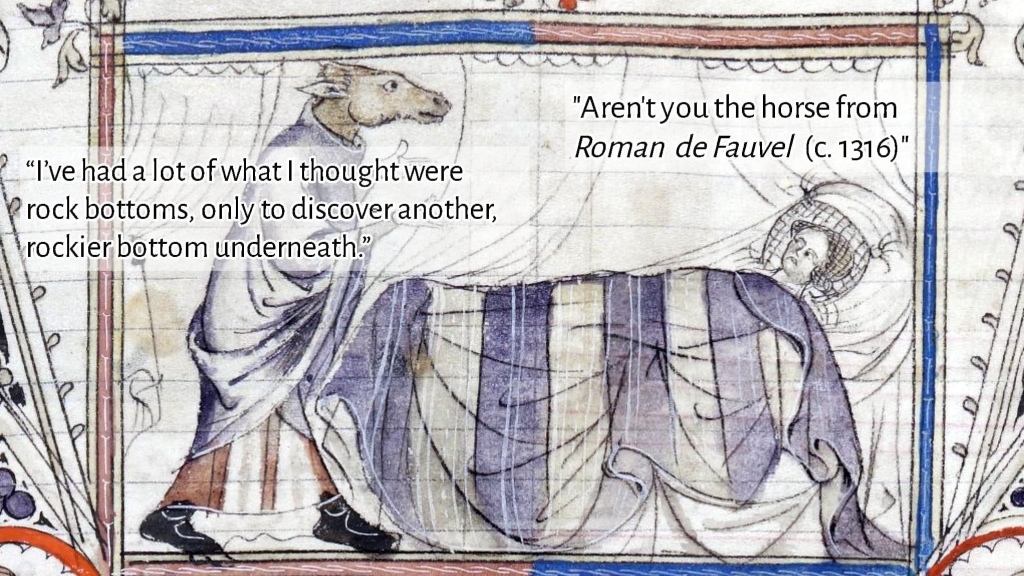

“Le jugement contre Fauvel est déjà prêt, et il sera jugé; lorsqu’il aura été condamné, il subira le châtiment éternel avec le prince des démons.” [“The judgment of Fauvel has already been set, and he will be judged. When he is condemned, he will undergo eternal punishment with the Devil.”] – le Roman de Fauvel (p. 647)

“Somebody sung this song for Satan.” – alleged backwards-recorded lyrics of the Mister Ed theme song

As I said a couple of weeks ago, I tend to use the end of the year to catch up with books too long or complicated to try to squeeze in during busier times when I’m more actively researching or trying to hit my reading goals. This tends to go doubly if it ends up being a year when I try to get through any books in French, my only true second language. My French speaking skills have atrophied to a desolate level by this point in my life, but because it’s much easier to practice, my reading comprehension remains strong, and I try to keep up with it semi-periodically. Good thing too, honestly, because earlier in the year during my medieval research for The Gourd and the Stars, I stumbled across the existence of the delightful and dark Roman de Fauvel, and I desperately wanted to read it; but as far as I can tell, it has never been fully translated into English (or there are no readily available editions of it). So, I had no choice but to get the 2012 Librairie Générale Française edition and hope its medieval French was as comprehensible as Christine de Pizan’s has been for me in the past. Dear readers, it was, and this week I want to introduce you to the apocalyptic poetic vision of two French government clerks and the literal worst thing they could imagine happening: what if we let a horse rule France?

Okay, Fauvel isn’t quite that simple, but it is perhaps as funny to you as it is to me, sitting around in the year of Our Lord 2023, where everyone’s governments seem to be at best incompetent and at worst, gone genocidin’, to imagine being this horrified by an animal potentate. I, frankly, confess myself willing to hear Candidate Equus out at this point, particularly if he has a plan for universal healthcare or campaign finance reform.

But bringing up Animal Farm is apt because, at its heart, Fauvel, too, is a political allegory, and exactly the sort of medieval animal fabliaux (fable) from which Orwell’s story descends. Medieval fabliaux are the literary link between ancient beast fables like Aesop’s and modern animal allegories like Animal Farm, while Fauvel itself is the literary offspring of perhaps the most famous medieval French allegorical character: Reynard the Fox.

The Reynard stories are a literary cycle of roughly twenty-six surviving tales centered around the trickster character of Reynard and a large cast of anthropomorphic animal figures that operate as a satire of contemporary society in 12th and 13th century France and Germany. Like many of the animal allegories that came before and after them, as well as non-European folklore traditions like those of Raven and Coyote in indigenous North America, or Anansi in Akan West Africa, the trickster character almost inevitably becomes the fan favorite of the audience. Indeed, these stories, and Reynard in particular, were so popular that they literally changed the languages of the European countries they touched. The original Old French word for “fox” was goupil, a gloss of the Latin vulpēcula, but, as my Flight of Virtue peeps already know, after the 13th century, it changed to renard, which became the standard French word for the animal. Similarly in English and (Low) German, the name of side character Martin the Ape’s son, Moneke, became the word for the whole animal—monkey—in those languages.

For all of the trouble he causes, Reynard was still, like most traditional trickster characters, a sympathetic character, which is where he and Fauvel start to diverge. While there is definitely an element of humor to the pompous and vain Fauvel, he is meant to serve as a sign of deep political and religious turmoil, and as such, he is decidedly darker than the clever and light-spirited Reynard. In this, Fauvel is more spiritually aligned with more ambiguous trickster characters such as Loki in Norse mythology. Many of the stories involving Loki in Scandinavian lore are dead funny, but ultimately, like Fauvel, the god of mischief is an apocalyptic figure in the Norse conception of their gods and the universe. He is responsible for the death of the Norse “son of god”, Baldr, and is the father of Fenrir, the wolf who will kill Odin, and Jörmungandr, the serpent that will kill and be killed by Thor during Ragnarök, the end of the both the Norse gods and the world. And like Fauvel, Loki is doomed to be punished and conquered in the end.

The Reynard stories and major sources for Norse mythology like the Prose Edda come out of the same roughly two centuries, but the Roman de Fauvel is a product of the 14th century—about a hundred or two years later. Firmly in the so-called High Middle Ages, Fauvel is both the culmination of what is now widely recognized as the period’s literary renaissance and the harbinger of a rapidly deteriorating political climate in France that will ultimately lead to the start of the Hundred Years’ War in twenty years.

Fauvel is held as having two authors: Gervais de Bus and Chaillou de Pesstain. Gervais is the primary author, the composer of the poem’s two books of 3,280 couplets in 1310/14, while Chaillou was apparently a fan who wrote an additional 3,000 verses in 1316/17, expanding on Gervais’ original text. This isn’t terribly unusual for literary works of the time. One of Fauvel’s biggest influences outside of Reynard, particularly in the Chaillou bits, is Guillaume de Lorris’ Le Romance de la Rose, an allegory of courtly love. Lorris’ original text of roughly 4,000 lines is comically dwarfed by the much more famous version enhanced by Jean de Meun’s almost 18,000 lines of additional text. As we saw with the different versions of the Octavian romance a couple of weeks ago, because medieval authorship was much more fluid than our conception of it, aside from a potential textual reference somewhere in the work, none of this was seen as illegitimate or plagiaristic. Nobody really “owned” Reynard or Fauvel or the lady Rose, so there wasn’t the modern artistic line between the canonical text and its sequels, adaptions, and ostensibly fan fics. Just as the twinned Lorris/Meun version of Rose is generally held as the Romance of the Rose, Fauvel as we know it is the hybridized Gervais/Chaillou text.

Our oldest version of the text is manuscript BN fr. 146, which was copied by Chaillou himself and is famous for both its lively miniatures and its detailed musical notation for the verses of the poem meant to be sung. This notation is some of the best preserved examples of early ars nova, or “new style” of late medieval polyphonic music, and it has been postulated that the music of Fauvel could be the work of Philippe de Vitry, the leading music theorist and composer of the period. Because of its importance to the history of European music theory, arguably the music of Fauvel is more widely known and studied today than its text.

Fauvel’s historical backdrop, as I said, is deeply entwined with the decades right before the start of the Hundred Years’ War and in the rapidly deteriorating authority of France’s ruling dynasty, the House of Capet. Though still three kings out from the dynastic collapse that would lead to both the war and the ascension of the cadet branch of Valois taking over the throne, the seeds had already been sown by the king in power when Gervais began writing: Philippe IV. While his standard epithet in French annals is le Bel, or the Fair, for his handsome appearance, his more telling nom de guerre is le Roi de fer—The Iron King—for his inflexibility to his people and enemies alike. Medieval folks would know Philippe for his wars with Edward I of England and with Flanders, and his spats with the pope and his barons for more and more royal control of France’s territory, but what modern people likely best know him for is being the king who wiped out the Templars and their last Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, in 1307. Although a clerk in Philippe’s chancery and therefore a part of the civil service that the king was building to undercut the power of the nobility, Gervais composed Fauvel as an (albeit indirect) indictment of Philippe and the direction he was taking France. Chaillou’s additions compound this under the reign of Philippe’s son, Louis X—whose historical epithet le Hutin—The Quarrelsome—shows that the gloves had really come off as the political climate continued to sour.

After all of that set up, the plot of Fauvel, like most allegories, is fairly straightforward. Fauvel is a fallow-colored (light brown/dun) horse (though the text also calls him roux, or redheaded—which may be a reference to the medieval tradition that Judas Iscariot was red-haired) who rises to prominence in France to the point where all the religious and secular authorities answer to him and the people follow his lead. Unlike a standard trickster like Reynard, Fauvel isn’t particularly clever, but he is able with his mere presence to deceive those around him into doing his bidding. This is perhaps simply due to his nature, which is encoded in his name. Fau-vel is “False Veil” in medieval French, and even the individual letters of his name (if you make the ‘u’ a Roman ‘v’) are meant to be an acrostic of six vices: Flaterie, Avarice, Vilanie, Varieté, Envie, and Lascheté (Flattery, Avarice, Vileness, Variability, Envy, and Laxity). Because he himself isn’t cunning enough to gain prominence over others, Fauvel’s luck is deemed to be due to the graces of Dame/Lady Fortune.

The poem illustrates Fauvel’s rise by having him become “too good” to live in a stable anymore. He instead lives in a palace where he can receive the many important personages who come to pay homage to him, like the pope and the king, and house the new aristocracy he installs over France, which is comprised of allegorical lords and ladies representing various sins and vices. But Fauvel cannot entirely shed his true nature, so he must fit out the palace with a manger and hay rack for himself, and his kingdom pays him court in a distinctly equine manner. In what becomes the dominant image of the entire poem (visible in the miniatures on the manuscript page above), the various high and lowly subjects of France show their dedication to Fauvel by frotter (rubbing) and torcher (currying) him as if they are his grooms, with each social estate responsible for brushing different parts of his body. This is also the origin of the poem’s most lasting linguistic legacy—the reason why one is said to “curry favor” in English is a bilingual corruption of the original idiom drawn from Norman French familiarity with this story, where one would be said to “curry Fauvel.”

After a while, Fauvel grows bored with his situation and decides that what he now needs is a wife. Considering his options, he concludes that the only lady worthy of him is Fortune herself, so he and his entourage sail to her kingdom, Macrocosme (Macrocosm) so he can propose. He does this in a comically drawn out parody of courtly love poetry, where Fauvel dramatically attests to the standard symptoms of lovesickness and to the incomparable charms of his lady love. Like all allegories of her, though, Fortune is a chaotic neutral figure and not one who can be appealed to by force or persuasion. The poem delineates this by describing her as “[q]ui n’estoient ne bonnes ne beles” (II.1919), that is, neither good or bad, beautiful or ugly—comparing her vividly to “[a]ins semblent estre crapodines [p]oingnans par dedens comme espines” (II.1920), or the kinds of toads that medieval people believed would change color in the presence of certain poisons. She emphatically and violently rejects Fauvel’s proposal, calling him vain and stupid (he is) to have imagined that he could possibly be worthy of someone like her. Fauvel isn’t initially deterred and responds by redoubling his efforts as if Fortune is just playing the part of a coy mistress in a love poem, which Fortune slaps down just as hard.

But seeing that Fauvel might be too stupid to take even the most vehement of rejections, Fortune, who by her double nature consorts with both vices and virtues, offers one of her ladies-in-waiting, Vainglory, to him as a bride instead. Fauvel, showing the emptiness of the wild declarations of courtly love, immediately abandons his original suit of Fortune and happily marries Vainglory instead. The allegorical lords and ladies attend Fauvel’s grand wedding ceremony, which culminates in a jousting tournament between the vices and virtues. The virtues technically win, but Fortune says that Fauvel and his court are destined to be in ascendence for a certain period of time because he is the harbinger of the Antichrist. Like the Antichrist and as my flavor text notes, Fauvel will eventually be defeated and punished, but not until great destruction and suffering comes to France through him and his legion of unholy offspring with Vainglory who will rule the kingdom until the apocalypse is over.

In spite of this real downer of an ending, the poem itself isn’t entirely pessimistic. Gervais and Chaillou know that, unlike the Norse Ragnarök, the Christian apocalypse is not final and that God is above its evils, which he will eventually defeat. They might lament Fauvel’s power in the immediate, but they know his downfall has been preordained. While Fortune is unpredictable, they go to great lengths to remind the reader that she isn’t evil like Fauvel, even going so far to designate her as a daughter of God and the sister of virtues like Wisdom and Reason. Her wheel brings people’s situations high and low, but her rejection of Fauvel is a confirmation of God’s ultimate omnipotence over the forces of darkness and this fallow-colored fifth horseman of the apocalypse. That’s why Gervais can ignore the frightening vision he’s just concocted and end his poem with the standard troubadour call for something to drink to quench his thirst (after so much talking/singing), and Chaillou can tack on an extra couplet with a similar demand to the reader to let the scribe go off and have some fun now that his work is done. Horse-kings come and go, but artistic tropes forever.

Leave a comment