Somtym byffell ane aventure,

In Rome ther was ane Emperoure,

Als men in romance rede.

He was a man of grete favoure

And levede in joye and grete honoure

And doghety was of dede.

In tornament nor in no fyghte

In the werlde ther ne was a better knyghte,

No worthier undir wede.

Octovyane was his name thrughowte;

Everylke man hade of hym dowte

When he was armede one stede.

- Octavian, lines 13-24

Some of you remember the good old days when this was an ancient Egypt/Roman blog because my God’s Wife books consumed my every waking thought. Since I’m tinkering with a return to that universe in the future, I’m sure we’ll find ourselves eyeballs-deep in that nonsense soon enough. But until then, I’ve stumbled into a neat (in both senses of the word) bridge between that and my current preoccupation with the medieval European world, and I’m here to share it with those of you who weren’t forced to take a Chaucer class in college because Advanced Shakespeare was full.

But I’m grateful to my Chaucer class for two reasons. It introduced me to its instructor, Kellie Robertson, internationally respected Chaucer scholar and chair of the aforementioned Medieval and Renaissance Studies program that I fell backwards into. Secondly, it gave me a rigorous introduction to Middle English as a language; which may not seem particularly useful to many of you, but as someone who’s had to half-ass teach herself Latin and Middle Egyptian, it’s handy to be able to have at least one language besides French that I can read in citation with confidence (while I much more slowly piece together Old English). That said, Middle English isn’t super difficult to pick up, if one is interested—the best advice Professor Robertson gave us was to sound out words phonetically as if you’re trying to say them the exaggerated way a Scottish person in a movie would. You’d be astounded how far you can get in The Riverside Chaucer by cosplaying that you’re an intellectual Shrek.

Anyway, a single, very intense class later, and I can read Middle English as comfortably as Elizabethan/Early Modern English, which opens up a whole world of early English literature that is too niche to have merited full translation into Modern English. Most of the pre-Chaucerian literature of England was heavily influenced by what was being written on the Continent, particularly in France, which was a direct result of the continued dominance of French culture among the English nobility since the Norman conquest in the 11th century. Much of the English audience for literary works up through the 14th century would have likely spoken French as their first language and might have been essentially foreigners to Britain by birth or lineage.

But in the late 13th century and into Chaucer’s era in the 14th, through time and increased military antagonism between England and mainland Europe (and France in particular), a distinctly English culture began to emerge. The English aristocracy were more likely to have been born on the island, and if they spoke French, they increasingly did so as a second language. Perhaps more significantly, the social structure of late medieval England had led to the emergence of a large and prosperous urban middle class of burghers and merchants, who had both sufficient leisure to become literate and the interest in acquiring the trappings of sophistication that buying books gave them. This resulted in not only more literature being written in the contemporary English vernacular (what we’d call Middle English), but more French literature being translated into English, rather than merely being circulated in untranslated French. Today, I thought we’d take a look at one of the more popular examples of the latter: the 14th century Middle English translation of the 13th century French Octavian Romance, starring you’ll just never guess…

It’s called a hennin, and yes, I know it’s more from the 15th century than the 13th or 14th, but it’s still what most people envision as “medieval.” Anyway, much in the way that the great Roman poets slunk out of the ancient period through medieval reworkings like the Ovide Moralisé, Roman history was as fascinating to people in the Middle Ages as it is to us today. Great Roman historical figures were as common as Alexander the Great and Charlemagne in medieval literature, and because he was seen as the benevolent emperor who united the world and presided over the Pax Romana, Octavius—Caesar Augustus—was the Roman king par excellence.

As we discussed in my entry about Christine de Pizan’s Othéa, where we touched on the Ovide Moralisé, there was a medieval legend that the Sibyl of Cumae had told Octavius about the coming of Jesus Christ, which like with Virgil’s supposed poetic prophecy about the same, gave Octavius a sort of honorary Christian status that made him more “appropriate” to valorize in contemporary romances and chansons de geste. The original 13th century Picardian Old French couplet romance Octavian is the oldest surviving work we have that so heavily features him, but this poem was so popular that local versions of it survive throughout Europe, not just in England (Four Middle English Romances, ed. Harriet Hudson, p. 39). Some of this was Octavius’ posthumous reputation, but as we’ll see—because his story largely gets hijacked by his sons(!)—a lot of Octavian’s popularity was because of its successful incorporation of at least a dozen of the medieval world’s favorite literary tropes.

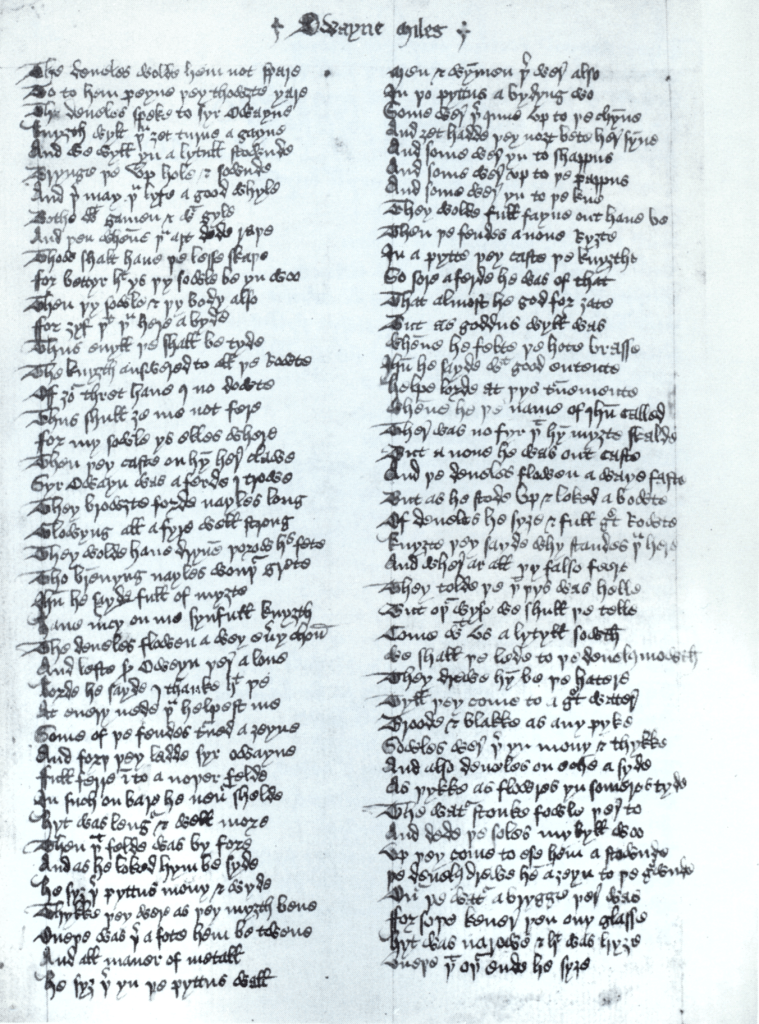

The Old French poem survives in a single Anglo-Norman manuscript (ibid), which was the basis for two Middle English translations. These translations are both thought to have been composed in the 14th century, but their earliest manuscripts come from the mid-15th century. They both also trim the much longer original French romance to roughly 1800 verse lines, but aside from these commonalities, the translations have significant differences, in part because they were composed in different geographical regions at a time when there was a wide linguistic gulf between northern and southern English (some of which continues up to the present day). While both manuscripts came out of the English Midlands, the so-called Southern Octavian is written in a dialect consistent with medieval Essex, while the Northern Octavian has a distinct Yorkshire syntax.

The Southern Octavian is thought to have been transcribed, if not written, by the 14th century poet Thomas Chestre, who composed several other Middle English romances, because the Southern Octavian shares the same Essex dialect and even directly copies some of the end rhymes that Chestre reuses throughout his works—it also utilizes the peculiarly English six-line aaabab verse structure popular in Chestre’s time. Conversely, we have no putative author for the Northern Octavian, which in addition to its different dialect, retains the original poem’s more typical twelve-line, tail-rhyme stanzas. However, the Northern Octavian abandons the looser, “more parenthetical” (ibid) style of both the French original and Chestre’s Southern Octavian for a more straightforward, linear narrative, which is why it is the more common version to find these days, and is therefore the iteration I read (and the one we’ll be talking about). The Northern Octavian also shows a progression away from the oral tradition all medieval romances came out of toward a literature that was primarily read instead of heard. It still opens with the classic appeal to the reader to listen to its invisible narrator, but unlike the Southern Octavian, it does not renew these appeals throughout the narrative when the scene changes, demonstrating the changing way stories we consumed during the period of its creation.

So what exactly is Rome’s favorite autocrat getting up to in this story? Well, we begin the narrative in a somewhat historically familiar place: Octavian is upset because he has no heir, despite being married to his wife for seven years (the empress is unnamed in the story, but it’s funnier if you imagine all of what follows happening to Livia…). After finding him literally crying himself to sleep over this, the empress suggests that they build an abbey to the Virgin Mary as a bribe to get her to intercede on behalf of their childlessness. The imperial couple build the abbey and, to quote whoever did the write-up on the Wikipedia article, “the empress is pregnant with twins!” (both boys). But here is where the first of the medieval tropes enters the plot—The Calumniated Wife, made famous by the Constance and Griselda-style romances of the period. In this trope, the virtuous wife is accused of sexual infidelity, which usually amounts to treason against a royal spouse, and has spend the rest of the narrative going through various trials to be vindicated. Obviously, like many of the tropes we’ll encounter in this story, this is far older than the Middle Ages, but this was an era where many of these motifs were not only repeated, but expected in most popular stories.

Who does the accusing in these stories changes from tale to tale, but in Octavian, it is Octavian’s mother who claims that the empress is pregnant not by him, but by one of the kitchen boys. In the next frankly historically accurate thing to happen, Octavian immediately kills the kitchen boy, no investigation or questions asked, and accuses his wife of treason. Bonus points if you picture that it’s milquetoast Atia somehow getting a march on Livia.

Anyway, Octavian decides to burn his wife and sons at the stake (the punishment for treason), but is persuaded to commute their sentence to banishment when the tearful empress begs him to baptize the boys first so they aren’t condemned to Hell. The empress and boys then leave Rome, traveling through a dark forest until an ape and a lioness emerge from the woods and each snatch away one of the children (Medieval Trope #2: Semi-Magical Animal Involvement). We can label these animals as “semi-magical” because neither animal takes a child with the intent of killing it. The distraught empress decides that this latest misfortune is punishment for sin, and she undertakes a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in response. On the way, she finds the lioness who took one of her sons suckling the boy like her own cub, and she is reunited with him. The lioness refuses to leave them and the whole party continue onto Jerusalem, where the Christian king there recognizes the empress and takes her into his court for protection. He becomes the guardian and liege lord of her son, who is christened Octavian after his real father.

The poem then swings back around to the ape, whom outlaws strip of the second boy, and they then sell the child to a French merchant named Clement, who meets them returning from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Clement names the boy Florent and brings him back to be raised by him and his wife in Paris. Since he was taken from his mother as an infant, Florent fulfills Medieval Trope #3: Hero Who is Ignorant of His True Lineage (and frankly takes over the narrative from his father as the central focus of the story). But this is also where Octavian breaks with convention, by introducing Clement, a villein, or common person, as a major character in the rest of the story. While some of this is for decidedly comedic purposes—multiple episodes are used to highlight how Florent’s “inherent” aristocracy manifests next to his bourgeois foster father’s hyper focus on money, and how Clement doesn’t understand the rules of noble society—Clement is not solely a figure of mockery. Indeed, he ends up playing a pivotal role in our noble-born heroes’ ability to overcome the next challenge that is thrown their way in the guise of invading Saracens.

An unnamed sultan invades France and lays siege to Paris. The emperor Octavian arrives with an army to aid the French king, but the sultan’s forces are led by (Medieval Trope #4) a giant whom he has promised his daughter, Marsabelle, in marriage. The giant wreaks havoc on the Christian coalition army until Florent convinces Clement to let him join the fight. Clad only in Clement’s rusty old armor, Florent valiantly defeats the giant (Medieval Trope #5: The Poorly-Clad Hero Wins By Sole Virtue of His Prowess), and delivers its head to Marsabelle so the two of them can have a meet-cute. The king of France and Emperor Octavian are wowed by this magnificent young man, and Florent is knighted in appreciation for his valor. While the emperor recognizes that Florent can’t possibly be the son of a merchant, he doesn’t know he is in fact his son (Medieval Trope #6: Meeting Relatives Fail to Know One Another).

The narrative makes up for having the venal, somewhat bumbling Clement be the butt of an extended comic scene where he’s afraid he’s going to have to pay for the feast the king and the emperor throw Florent by making him the hands-down hero of the next sequence. The sultan has regroup and the fighting has resumed, but during one of their several amorous clandestine encounters (Medieval Trope #7), Marsabelle tells Florent that she will convert to Christianity (Medieval Trope #8), and that her father cannot be defeated while he still has his magic horse (Medieval Trope #9), a unicorn. Rather than Florent being the one who steals the unicorn from the Saracen camp, it is Clement who pulls off this trick, dressing up as a Muslim and conning the sultan out of the animal, because, as a traveling merchant, he can speak Arabic. This is a fantastic narrative choice which makes the escapade so much more believable than if Florent had tried to do the same. Clement gives Florent the unicorn, who in turn gives it to the emperor as a gift.

Despite this coup, the next series of battles go poorly for the Christians. Florent is injured, and he, the emperor, and the king of France are captured. But then, the king of Jerusalem shows up with his army, led by the young Octavian, and they defeat the Saracens once and for all. The empress has accompanied them to Paris, and with all the necessary information in the same place, young Octavian and Florent are both revealed to be the emperor’s long-lost sons, and the family is exonerated and reunited (Medieval Trope #10: The Innocent Are Vindicated and Medieval Trope #11: The Noble Family Reunited). Unmasked as the real villain, the emperor’s mother is condemned to death, but she kills herself first and saves everyone the trouble. Florent and Marsabelle are married, and the whole family returns to Rome together (Medieval Trope #12: Happily Ever After).

And there you have it—that’s how you turn a Roman emperor into a medieval king and what may have been at some distant point a garbled retelling of Suetonius into a fairly standard medieval romance. Academically, that Suetonius comment might sound a bit far-fetched, but if you squint right, I think pieces are there. Octavius’ tragically lost grandsons and adopted heirs, Gaius and Lucius, always depicted as a pair, become spirited away twins. Their unjust disinheritance by a wicked grandmother makes more sense if you realize that in history, their grandmother wouldn’t have been Atia, but rather Livia, whose posthumous reputation, whether true or not, was especially bad in Suetonius. Their actual mother would have been the maligned (and much more popular) Julia, who was the one accused of sexual misconduct in history. Despite their early deaths, both Gaius and Lucius would serve in the army (“become knights”), and one of them (Gaius) would specifically serve in Syria (the Holy Land). The Octavians show a still-recognizable Octavius—a just ruler who makes some truly spectacular errors in judgment, but the difference in the 13th/14th century from the 1st is that because he has (allegedly) acknowledged Christ as a god above him, he is permitted the restoration of his longed-for heirs after sufficient penance, a concept well outside the religious logic of the Romans. Sin may be a more nebulous force in Roman thought than it was in medieval belief, but to the minds of the Octavian authors, the presence of sin also opened the possibility of divine forgiveness, and to them, it is this forgiveness that can change the past and give Octavius back his grandchildren.

Leave a comment