“The following Tales are meant to be submitted to the young reader as an introduction to the study of Shakespeare, for which purpose his words are used whenever it seemed possible to bring them in; and in whatever has been added to give them the regular form of a connected story, diligent care has been taken to select such words as might least interrupt the effect of the beautiful English tongue in which he wrote…” – from the preface of Tales From Shakespeare

I had a mother, but she died, and left me,

Died prematurely in a day of horrors -

All, all are gone, the old familiar faces.

- ‘The Old Familiar Faces,’ Charles Lamb (excised from later editions of the poem)

Like many people, I have horror of throwing out books. This is why my office is a monument to one woman’s experiment to find out just how many bookshelves she can fit in that space (the current answer, always subject to revision, is eleven). A favorite indie publisher (Archipelago Books) sent an extra book with my order in recompense for a minor inconvenience, which in light of the situation mentioned, was both the best and worst thing that happened to me this week.

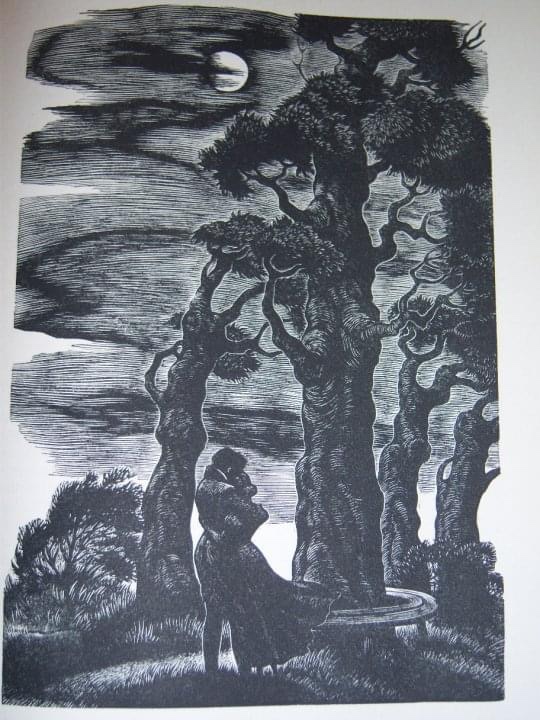

In addition to my own buying habit, which is formidable and more restrained than it appears from the outside, I have the usual collection of strays from library free bins, friends, and—inevitably at this point in my life—the dead. The two largest collections I have in that last category are books I inherited from my grandmother and those I inherited from my younger brother, Alex, and perhaps appropriately, they run the gamut of inherent quality. My grandmother’s books are some of the most beautiful books I own, among them a lushly illustrated 1920s edition of Little Women, and Random House’s edition of Jane Eyre from the same time, with Fritz Eichenberg’s haunting woodcuts.

In contrast, my brother, always a consumer of quantity over quality, left us to sort through a bookshelf’s worth of the cheapest trade paperbacks the mid-1990s and early ‘00s could furnish. Which is why “my” copy of The Lord of the Rings is a trio of bargain bin movie tie-in paperbacks—and I wouldn’t trade them for any other at this point. Neither me nor my parents could keep all of these books, but as a result of leaving us as a teenager (cancer sucks), my brother’s literary tastes were in flux and he had little bit of everything. I don’t know if his contemporary interests would have continued into adulthood, but when he died, we were both exploring Shakespeare and I’m assuming it was on one of our trips up to Stratford, Ontario for the Festival where he acquired a cheap Signet edition of Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales From Shakespeare (my brother never met a gift shop he didn’t like).

I don’t know if he actually ever got around to reading it, but I can’t point fingers there, because Tales has sat unread by me on my various shelves for nearly twenty years in the interim. I’ve always put it off because, I mean, I’ve already read all of the actual Shakespeare plays, so reading what I understood to be bowdlerized versions of them seemed pointless. But considering that Tales has been continuously in print since its initial publication in 1807, I decided that I should read it on its own merits as a literary and cultural artifact. And while I can can confidently tell you that the experience pales in comparison with the original plays, the exercise was more complex and unexpected than I anticipated, so I thought we could unpack that a bit. So, let’s dive in!

But first, some biographical background on the Lambs, because even I was unfamiliar going in. As in, I was like, “Mary Lamb—was she the one who had an affair with Byron?” (spoiler alert: she was not. That’s Caroline Lamb). Indeed, the Lambs we are concerned with were not from the gentry or aristocracy at all, but rather (much more interestingly for the time) only precariously middle class. Mary and Charles were siblings born in 1764 and 1775 respectively to John and Elizabeth Lamb in London, where their father worked as a legal clerk to a barrister and their mother as his housekeeper. Although eleven years apart in age themselves, Mary and Charles were the closest in age of their surviving siblings, and it appears as a result they were close emotionally as well. We don’t know many particular details of their early childhood, but Charles claimed it was Mary who taught him to read and arguably started him on the path to a respected, if modest, literary career.

While never well off, the family was moderately comfortable until the barrister’s death in 1792, when they had to move out of the accommodations he had provided. John Lamb continued to work as a clerk in the London Inns of Court, but they were never as financially secure as they had been previously. That said, Charles showed an early aptitude for academics and before his death, his father’s employer sponsored his admittance to Christ’s Hospital, a long-established charity boarding school in London. Charles excelled at Christ’s Hospital, despite the typical brutality of the English boarding school system, although his stutter would ultimately prevent him from being able to attend Cambridge (stuttering being seen as a disqualification for training for the Church). While this would deny Charles the opportunity to advance his family socially through one of the few channels of upward mobility available in the Regency Era, he did have the good fortune to meet Samuel Taylor Coleridge at Christ’s Hospital, and their lifelong friendship would give Charles access to the cream of English literary society and make him a part of the Romantic movement. But this modicum of happiness and stability lay a few years in the future, and the Lambs had some dark times ahead of themselves before that.

While Charles was attending school, no such opportunity existed for his sister Mary, even when she had been his age. As the eldest surviving daughter of the family, she spent her childhood and early adulthood helping their mother care for their own home and that of the barrister. After the barrister’s death, she would become a seamstress to help the family take in money, something that became increasingly important as her parents’ health failed and they became unable to work. Her mother developed debilitating arthritis which rendered her essentially an invalid, and by the late 1790s, her father had advanced dementia and needed continuous supervision. Charles himself left Christ’s Hospital in 1792 at fourteen in order to find work to help shoulder the burden. He worked as a clerk for a variety of merchant houses, but in 1795 he suffered the first in a lifetime of psychological breakdowns, and spent several months in a private mental institution, presumably at Mary’s expense and leaving her alone with their parents.

By 1796, things were bleak. Charles was out of supervised care and back at work, but Mary was still largely responsible for their invalid parents’ care while still trying to earn a living as a seamstress. Worse yet, an elderly aunt had also moved in with the family because she was too ill to live on her own, and the Lambs’ older brother John had come home to recuperate from an accident. Trapped in a house with four incapacitated adults, Mary was caring for them, training a young apprentice for her seamstress business, seeing to all of the regular chores for a household of seven people, and still attempting to do enough sewing to actually make any money. Caregiver burnout was practically inevitable, but Mary wasn’t going to toddle off to check herself into a sanatorium like her brother did. By the time anyone knew how bad the situation was, she’d be dragged there involuntarily.

As far as the events can be determined, on September 22, 1796, Mary was making dinner for everyone when her apprentice said or did something that annoyed her. She shoved her out of the way, which caused Mary’s mother to start shouting at her for handling the girl too roughly. Elizabeth Lamb continued to berate Mary while the invalid aunt and her brother looked on, and it appears that Mary just snapped under the weight of her mother’s diatribe. She grabbed the kitchen knife and stabbed her mother in the chest until she was dead, stopping only when Charles arrived on the scene to take the knife out of her hand.

Mary Lamb was almost immediately declared not responsible for Elizabeth Lamb’s murder by reason of insanity (“lunacy” in the legal terminology of the day). Her older brother wanted to commit her to a public mental facility—a truly horrific prospect in that time—but Charles convinced him to have Mary sent to a private institution in Islington founded by a physician friend. She remained there for six months regaining her psychological stability, and Charles took over responsibility for her care. He had enough emotional intelligence to realize taking Mary back to the family and placing their care back on her was an astoundingly bad idea, so instead when she was released from the mental institution, he set her up in a house in Hackney where she was looked after by her landlords and visits from him while resuming her seamstress work. This would continue until 1799, when, with both their father and aunt having passed away, Charles brought Mary back to London to live with him. They would remain happily together, despite both of them occasionally checking in and out of mental hospitals throughout their lives, until Charles’ death in 1834. After this, Mary lived another thirteen years, still navigating episodes of chronic mental illness until her own death in 1847.

But despite psychosis, manslaughter, and the threat of penury, as I alluded to earlier, the Lambs enjoyed deep friendships with many of the leading figures of Romanticism, including Coleridge and William Wordsworth, as well as prominent philosophers like Mary Wollstonecraft’s husband, William Godwin. Wollstonecraft was dead by the time Godwin was publishing Charles’ poems and essays, but Mary was friends with Godwin’s second wife (also named Mary—Byron groupie Claire Clairmont’s mother), and it was Mary Godwin who suggested that Mary Lamb write something for a series of volumes the Godwins published for children. Taking their love of Shakespeare, especially for the idea of the plays as something one read as opposed to watched, Mary and Charles began collaborating on a book of prose adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays for a younger audience. The end result would be Tales From Shakespeare.

For the sake of content and perhaps brevity, Tales does not cover all of Shakespeare’s plays. The Lambs chose to adapt twenty of Shakespeare’s thirty-nine (if you include Edward III) plays—thirteen of the comedies and seven of the tragedies—with Charles writing all of the tragedies except for Cymbeline, and Mary writing that and all of the comedies. Left out of Tales are all of the history plays, all of the antiquity plays, plus three of the comedies (The Merry Wives of Windsor, The Two Noble Kinsmen, and, strangely, Love’s Labour’s Lost). A lot of this is probably why I’ve been putting off reading Tales—I love pretty much all of Shakespeare, but I am here for the history and antiquity plays. To me, the Lambs basically left out my favorite plays that aren’t Macbeth.

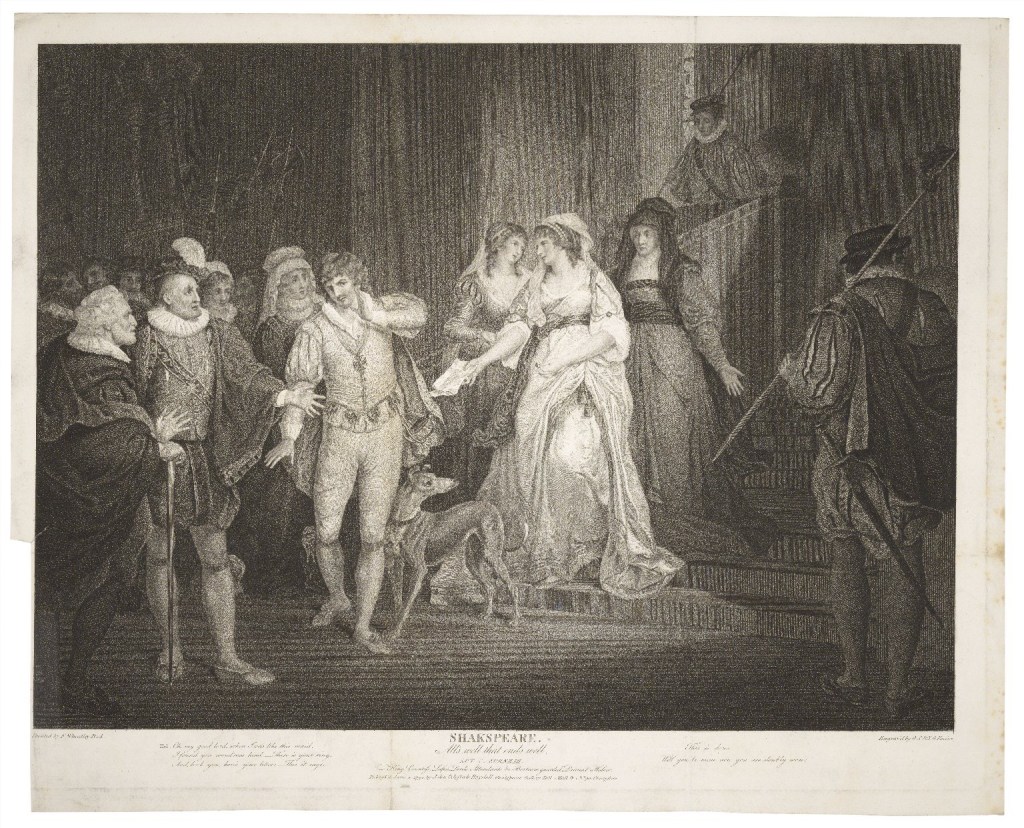

As I also alluded to at the beginning, I went into Tales expecting very sanitized versions of the plays, and while the book is self-described as being aimed at a “young” (Charles’ emphasis, not mine), largely female readership (young girls likely not having the access to the originals that their more formally educated brothers would), it seems ungenerous and simplistic to tar the Lambs with Thomas Bowdler’s brush. While dodging some questionable morality by leaving out most of the antiquity plays and the histories, the Lambs keep most of the so-called “problem plays” with their bizarre plots and NSFW story beats, and keep them largely intact without being explicit. It takes real outside-the-box thinking to decide that explaining wtf is happening in the three Henry VI plays is too much for kids, but laying out everybody’s deal in The Winter’s Tale or All’s Well That Ends Well is worth the effort. I mean, no one made Mary Lamb adapt Measure For Measure—she chose to keep that weirdo (for the record, I love MFM).

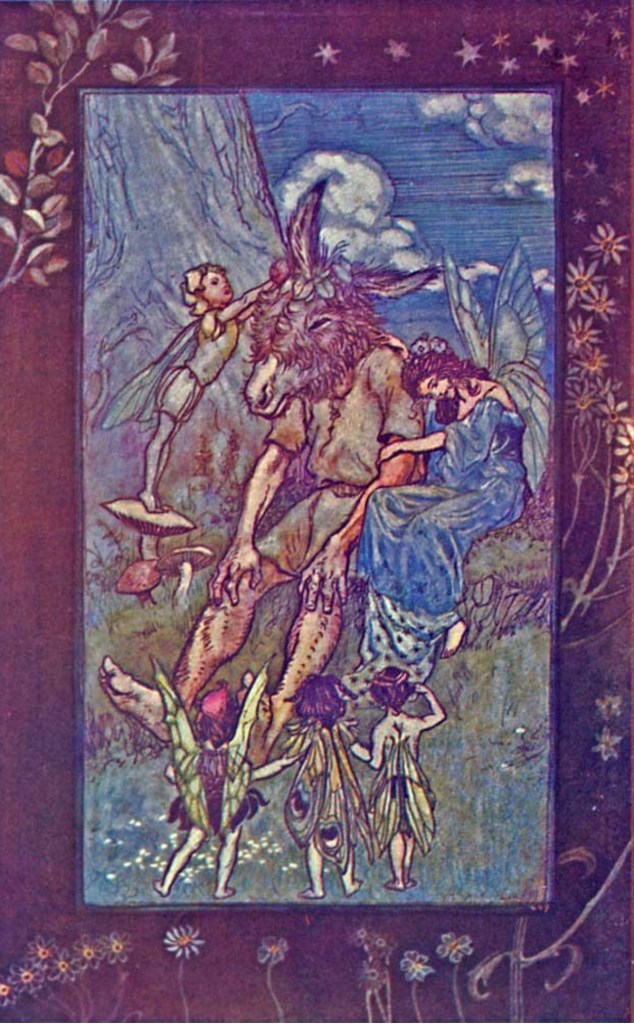

Some of this in-between-ness of Tales comes from its place in the history of children’s literature. As Professor Sylvan Barnet discusses at length in an afterword he wrote for the 1986 Signet edition I have, children’s literature was both a newly burgeoning market at the turn of the 19th century in the western world and at a sort of crossroads. The rationalism of the European Enlightenment had pushed traditional fairytales out of fashion as useless superstition (Tales, 316), and authors writing for children were replacing them with largely realistic, didactic stories. A good example of this is Mary Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories from Real Life, which has the tongue-numbing subtitle of: With Conversations Calculated to Regulate the Affections, and Form the Mind to Truth and Goodness. Mary does what it says on the tin and lays out a series of realistic morality stories told to two young girls by their prudent governess, Mrs. Mason. Charles Lamb, on the other hand, felt that this new trend denied children the chance to use their imaginations and explore creative expression, and Tales From Shakespeare was intended to push back against the pure realism of Enlightenment literature (Tales, 317). This is why the Lambs were willing to cut most of the comic characters out of Shakespeare’s plays to streamline the stories, but mythical characters like Ariel and Puck are retained, for enjoyment’s sake.

The tales themselves are fairly straightforward in their retellings of what would be called the “A” and “B” plots of these twenty plays, while cutting any extraneous characters or remaining C plots. For example, Mary’s adaptation of The Merchant of Venice goes through the pound of flesh plot between Antonio and Shylock, as well as a truncated explanation of Bassanio’s courtship of Portia, but cuts out the Jessica/Lorenzo plot entirely, save for a single reference when Shylock’s sentence is pronounced. Fools, servants, and lower class characters are cut except where they are strictly necessary to the main story, as with the shepherds of The Winter’s Tale, or Lear’s fool. Most of the time, this is merely unfortunate from a stylistic appreciation standpoint, as you miss classic characters like Touchstone and Juliet’s nurse, but occasionally the result is bizarre. The worst being A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where Mary’s decision to completely cut the worker’s play plot and its characters leaves her in a narrative jam when she has to explain the trick Oberon wants to play on Titania. So she’s stuck hastily summoning Nick Bottom as a nameless “clown” to assume his ass-inine interlude with the drugged fairy queen.

How much of Shakespeare’s language or phrasing also varies wildly depending on the play in question. The Lambs wanted to incorporate as much of the Bard’s famous words as they could, but not at the expense of making the stories intelligible to a young audience. Charles keeps in a lot of the dialogue language from Macbeth and Romeo & Juliet, because of its beauty and fame, but doesn’t do the same for Hamlet, a play most famous for its language. Similarly, Mary works in the whole “Come away, come away Death” song from Twelfth Night simply for the sake of its poetry, but includes reams of straight-copied dialogue from Measure For Measure clearly just for the sake of trying to explain what the heck is going on.

In the end, I agree with Professor Barnet that the Lambs’ Tales are “simplified but not moralizing” (Tales, 326-7), at least by the standards of their day. They try not to step out of frame to moralize the plays to their audience—which is good, because the few times they do, it tends to be unfortunate from a posterity standpoint (while not overly racialized, the Lambs have typical white 19th century European attitudes towards Jews and Blacks that come through in Merchant and Othello). Another thing that caught my attention as I was reading was a strange aside by Charles about mental illness in King Lear:

“But upon examination this spirit proved to be nothing more than a poor Bedlam beggar, who had crept into this deserted hovel for shelter, and with his talk about devils frightened the fool, one of those poor lunatics who are either mad, or feign to be so, the better to extort charity from the compassionate country people, who go about the country, calling themselves poor Tom and poor Turlygood, saying,

‘Who gives anything to poor Tom?’ sticking pins and nails and sprigs of rosemary into their arms to make them bleed, and with such horrible actions, partly by prayers, and partly with lunatic curses, they move or terrify the ignorant country-folks into giving them alms.” (Tales, 139)

When I first read this passage, I was scornful that Charles seemed so dismissive of mentally ill people, given his own struggles and those of his sister. But as I reread it, and re-parsed his long, Romantic run-on sentence, I realized his anger was for those who pretended to be mentally ill, not those who were, and that made much more sense. Having known the depths and cost of real psychosis, those faking it for money and sympathy must have been infuriating to him. Mary knew these costs too, as fear of her potential notoriety after her mother’s murder kept her name off the title page of the book she wrote the larger share of for thirty years. Her name wouldn’t appear on Tales until 1838, when the book had entered its seventh edition.

To close, I can’t say that Tales From Shakespeare is as good as reading Will Himself, or even that it’s particularly necessary reading, but it is an important piece of literary history nonetheless. Not just because it was at the forefront of the 19th century children’s literature revolution that formed the basis for the entire modern genre, but because it was at the forefront of the 19th century Shakespeare revolution that transformed the Bard from an important English writer into the most important English writer. Those us living in the 21st century where Will is held up as a god sometimes forget that there was a significant span of time between Shakespeare’s death and the mid-19th century where he was not especially popular or revered. While certainly never entirely forgotten, his preeminence as we think of it was really the product of a twofold cultural revival in the 1800s. Most importantly, there was seismic shift in how Shakespearean plays were staged, particularly with the rise of the great tragic actors in England and the United States. But not to be underestimated was the literary trend helmed by the Romantics, where it became fashionable for the first time to read the plays. The Lambs understood this, and their grasp of the zeitgeist would change the way we read Shakespeare’s plays and how we teach them to the next generation. For better or worse, if you read Shakespeare in school, you likely have the Lambs to thank for it.

Leave a comment