A year and a half ago, I introduced all of you to Mary Wroth and her sprawling Jacobean pastoral roman à clef, Urania. In that post, I promised to keep my eyes peeled for an ultra-rare copy of Urania’s incomplete second part in the wild and report back if I successfully got my hands on it. Well, it was more expensive than I will usually stoop to, but this past spring I found one for sale (stateside too, as a bonus) and pulled the trigger. So here we are for Round Two on everybody’s favorite author-insert long-form fanfic! Strap in—because even as an unfinished manuscript we’ve got some great dozy storylines here.

I’m not going to rehash Wroth’s full biography (for something closer to that, click the link in the previous paragraph to go back to the original entry I did for Urania Part One). But as a refresher as to where we are in her personal timeline as she’s writing Part Two, I’ll reiterate a few highlights. While we don’t know exactly how much of Part Two was written concurrently with Part One, we can deduce that at least some of it must have been extent at P1’s publication in 1621, as P1 ends incongruously in the middle of a sentence that links up with the in-progress sentence that begins P2. Professor Josephine Roberts, the lead editor and compiler for our modern printings of both parts, believed that P2 was written by Wroth sporadically for about a decade (1620-1630) before she presumably abandoned the single holographic manuscript of P2, as P2 also ends abruptly in the middle of a sentence.

So in 1621-ish, in the presumed early days of P2’s history, Mary’s lawful husband, Sir Robert Wroth has been dead for about seven years, and her only child from that marriage, James, has been dead for five. James’ death has deprived her of most of any income she was receiving from the Wroth estate as male primogeniture entailed it away to the next male heir. She’s been carrying on an intimate relationship with her cousin William Herbert, the 3rd earl of Pembroke, since at least her husband’s demise, and has had at least two illegitimate children with him—her daughter Catherine and another son, William. This relationship is not approved of by any of their relatives, including William’s mother (and Mary’s beloved godmother) Mary Herbert, and a result she is largely estranged from them.

However Urania’s publication will knock out most of Mary’s remaining supports within a few years of its appearance. Her decision as a gentlewoman to formally publish P1, as well as the book’s barely-veiled dramatization of several real life scandals among the nobility will see her exiled from the court of James I, and William Herbert will end their relationship around the same time. She’s only in her mid-thirties in 1621, and will spend the next thirty years struggling in an obscurity so profound we’re not completely sure when she died. The decade she spent writing and rewriting P2 probably represent the last even marginally happy years of her life—a time where she might have still entertained some hope of a reconciliation with Herbert; perhaps received some financial support from him for their children; and despite its chilly reception, maybe dreamed of finishing P2 and publishing again.

But then Herbert, her beloved Amphilanthus whom she adored warts and all, died in 1630. This personal tragedy, coming less than a year after Urania’s dedicatee and titular heroine inspiration, Susan de Vere, countess of Montgomery, had also passed away, makes it seem pretty obvious that Mary just lost the will to keep writing and she left the manuscript unfinished. Additionally, if Mary was receiving any money from Herbert, that likely was stopped by his unsympathetic relations at his death, so her precarious financial situation, which she would struggle with until her own death in either 1651 or 1653, left her little time or energy to devote to her literary passions. Professor Roberts’ notes remark on the generally poor quality of the French paper Wroth was using to copy out the P2 manuscript—evidenced by the amount of ink bleed-through on the pages—which becomes just another testament to the downturn of its author’s life.

Indeed, the growing desperation of Mary Wroth permeates what she did manage to write for the second part of Urania. P2 is a book trying to be an episodic adventure romance like its predecessor, but is often overwhelmed by a distinct sense of melancholy and fatalism. To bring back the comparison I made in my first entry, like the second part of The Tale of Genji, P2 tries to show the second generation of its heroes and heroines experiencing new loves and new triumphs, but there’s this unshakable feeling in the narrative (whether conscious or unconscious on Wroth’s part) that they’re merely shadows of their parents seemingly doomed to retread the same stories. This impression of doubling and vague hopelessness is only intensified by the continued presence of the original cast from P1, who lurk around the story with the same sort of sad, sometimes almost ridiculous air that clings to the aging Genji as he watches his sons live their version of his supposedly glorious life.

At the end of P1, most of the (too many, frankly) characters have been happily or at least comfortably paired off. But P2 starts (once it finishes that mid-sentence cliffhanger) with announcing the death of major heroine Philistella, main heroine Pamphilia’s (Wroth) younger sister and stand-in for Wroth’s real life younger sister, Philippa, who died in 1620. This coincides with an adventure where Philistella’s husband, Selarinus, though grieving, almost immediately falls under the spell of an evil fairy who tortures him off and on for most of the manuscript when she’s not succubus-ing fairy children out of him. This might be a commentary by Wroth on her brother-in-law, Sir John Hobart, remarrying within a year of her sister’s death.

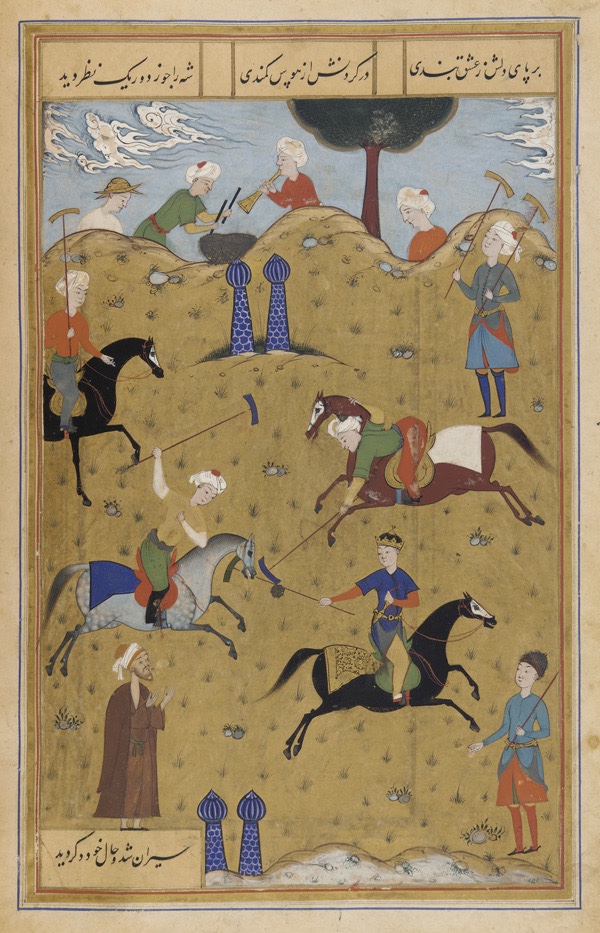

But death and estrangement are the major threads of P2’s plot, even when Wroth is trying to do other things. It’s clear that Wroth intended her focus to be on an expansion of her theme of unification from P1, but real life, and especially William Herbert (Amphilanthus), kept derailing her best laid plans. In P1, Amphilanthus and Pamphilia’s love and presumably impending marriage is supposed to represent a uniting of Western and Eastern Europe, with Amphilanthus as king of Naples and elected Holy Roman emperor in the west, and Pamphilia, as princess of Morea (a Renaissance-era Venetian colony on the Peloponnesian peninsula) and queen of the same-named territory in Anatolia (Turkey) in the east. The plot is meant to balloon this idea from an inter-European perspective to a more global one, as Pamphilia’s kingdom is threatened by an internal conflict in neighboring Persia, pitting a united Europe of her lover and friends against a usurping sophy and Islam in general.

The usurping sophy is a threat to his niece, but also to his neighbor Pamphilia, whom he threatens to marry by force. Her friends and Amphilanthus rescue her from this fate by defeating the false sophy’s Muslim army, and her brother Rosindy (Wroth’s brother Robert Sidney) rescues Lindafillia the true sophy. The unfinished P2 foreshadows that Lindafillia is destined to become the lover of the mysterious young knight Faire Designe, who is heavily implied to be the (unbeknownst) natural son of Amphilanthus, thus uniting the European West with the Middle East, and broadening the circle of interconnection begun in P1.

But even if East and West become one in Lindafillia and Faire Designe, it might not matter because the original East-West bond forged in P1 between Pamphilia and Amphilanthus becomes as irretrievably broken in P2 as it became in Wroth’s real world. And Wroth makes it clear that as much as she loves him, she places the blame at Herbert and his doppelgänger’s feet. In the story, Amphilanthus lets himself be convinced solely on hearsay that Pamphilia has married Rodomandro, the king or Great Cham (Khan) of Tartaria. Without bothering to corroborate this story, or you know, asking Pamphilia, he immediately marries the princess of Slovenia (Herbert’s wife, Mary Talbot’s stand in), and is horrified to discover later that the rumor is false. But the damage is done, and our lovers, unlike in real life where marriages to other people didn’t stop them, are parted forever. Pamphilia decides she might as well marry Rodomandro for real even though she doesn’t love him, and Amphilanthus spends the rest of P2 regretting his haste and becoming less and less integral to the movement of the plot. Like Genji, we’re assured continuously that he’s still as brave and handsome as he was before, but the textual evidence of this fades from view until Amphilanthus is little more than a figurehead reacting to events rather than causing them.

The growing ineffectiveness of the P1 generation in P2 would leave a less disturbing impression on the reader if one felt more certain that their kids were all right. But Wroth’s clear worries for her fatherless, illegitimate children (and arguably the children of her contemporaries) sublimates itself into one of the other core plots of P2. In that, a large contingent of the young princes and princesses are sailing to Naples to be cared for and tutored by Amphilanthus’ mother, the widowed queen (aka Mary Herbert), when their flotilla is scattered and the kids disappear. A large part of P2 is concerned with their frantic parents searching for their whereabouts, and freeing them from various calamities like capture by giants, imprisonment by magic, and—to circle back to the original P1 situation of Urania—left amongst shepherds in far flung villages. Near the end of the P2 manuscript, the children have all been found and a few of the most promising of the second generation like Faire Designe have begun to show their potential, but the future feels precarious and not just because things cut off mid-sentence.

Despite all of this, not everything about P2 is dark. One of the most fascinating aspects of the second part of the story is how Wroth subtly changes the characterization of the people she depicted as her biggest nemeses in P1: courtier and rival for Herbert, Mary Fitton, and Wroth’s late husband, Robert. Fitton’s doppelgänger, the proud and scheming Antissia of Romania returns in P2, and the first we hear of her in the story seems like more of the same from the first, where Wroth depicts her as literally mad with jealousy that she can’t have Amphilanthus. In P2, she suffers some of the most violent episodes of any character in the story, being almost sexually assaulted in front of her husband, the king of Negroponte, and later is nearly assassinated. Clearly, Wroth was still working through some personal issues with Fitton, but she never goes all the way, even in this, her fantasy fanfic. Antissia is saved by friendly forces before she is raped by pirates and doesn’t actually get killed later on. Wroth even sends her favorite benevolent deus ex machina, the mysterious priestess Melissea to cure Antissia’s madness. It might not exactly be a redemption arc, but it’s a lot from a writer who had clearly harbored so much resentment against her. Perhaps over the ten years of writing redrafts, Wroth grew more sympathetic of her former rival, to whom life had also turned distinctly unkind in the years since the two had been fighting over William Herbert. Dismissed from court after having her own illegitimate child (who died) with Herbert, Fitton had several more scandalous extra-marital affairs, another illegitimate child, and a couple of undesirable marriages to low-status men, and was persona non grata with her own family. Lonely and hard up herself, it wouldn’t be crazy if Wroth no longer held herself above Fitton as easily as she had once done.

But even more surprising than her change of heart toward Fitton is the softening of Wroth’s authorial relationship with her dead husband. In P1, Sir Robert Wroth appears in some of the worst characters—murderously jealous spouses, drunken bores, irredeemable gamblers. But in an almost complete about-face, Robert appears as only one character in P2: the gallant and lovelorn Rodomandro. In spite of being depicted as very much an outsider as the khan of Tartaria and someone Pamphilia is not in love with, nothing Rodomandro says or does is shown in a bad light at any point in the story. Like Othello, he is expressly depicted as Black, but also like the Moor of Venice, Wroth goes out of her way to describe him as very handsome. He adores Pamphilia, and consents to admire her from afar when she initially rejects him. Even when she finally agrees to marry him, he doesn’t push her to give or feel more than she wants to. He is loyal to his allies and fights bravely when called on to do so—he arguably fights more than Amphilanthus does in the story. Like Sir Robert, Rodomandro leaves Pamphilia a widow near the end of the manuscript, but one gets the sense that Wroth has had some time and distance from her unhappy marriage to discover an unexpected well of grace for the man who did, if nothing else, kept a roof over her head and tolerated her obsession with another man for ten years.

To wrap this up, I wanted to acknowledge a tragic bit of dovetailing involved with the unfinished P2 manuscript and Professor Roberts’ efforts to bring a modern, annotated version of both parts of Urania to both an academic and general audience. I suspect part of the reason why copies of the second part are so difficult to come by is the more fractured history of its editing and publication. A year after Professor Roberts’ publication of P1, and while she was still working on P2, she was killed in a car accident. This horrible turn of events led to two colleagues, Suzanne Gossett and Janel Mueller, taking over the project and spending the next three years sifting through her notes trying to complete Roberts’ vision. I think the end result is as seamless a book as could be achieved from incomplete notes on an incomplete manuscript. And in some ways, it is strangely hopeful. Urania itself was in part a product of Mary Wroth’s yearning toward a world where women could write and have greater control of their destinies. I’d like to think she would have been happy to know that a woman so committed to helping the world know hers a little better enjoyed a similar intellectual support of like-minded women that was so pivotal in her youth and her greatest dream for the future.

Leave a comment