“Hello! Would you like to change religions? I have a free book written by Jesus!” – Elder Cunningham, The Book of Mormon

We talked a little about how ancient mythologies absorbed and built upon one another in my entries about Set and demonic entities, but I thought this week we’d dig a little deeper and explore how the Red Lord is hardly an outlier in this respect. We tend to view many of the pre-Christian religions as static, certain people worshipping certain gods until Constatine had one really good day on the battlefield. But as usual, the truth is a little more complicated than that. The gods had a habit of wandering from place to place with traders and generals, building new cults along the way by adapting to their new homes.

One of these earliest migrant deities is the Sumerian goddess Inanna. Inanna is so ancient we’re not even entirely sure her Sumerian form is her earliest. Considering that her influence isn’t particularly remarkable before the conquest of the great Akkadian (post-Sumerian empire) king, Sargon, she might herself be the fusion of several older Semetic entities. Inanna is a sky goddess, the Queen of Heaven, associated with lions and the planet Venus, the morning star. By the time the Akkadians arrived, they had already changed her name to Ishtar, the name that she would be known by in the Babylonian and Assyrian empires that would replace the Akkadians.

It is through the Assyrians and their neighbors, the Hittites, that Ishtar likely made her way to Egypt, where she would maintain a following amongst the Egyptians as an adopted god, in no small part due to her similarities with Egypt’s own Queen of Heaven, Isis. Both goddesses are powerful members of their own pantheon and would be readily assimilated into the religions of others. Ishtar was the morning star, while Isis was the bright star, Sirius, through her absorption of the minor goddess Sopdet.

Both Ishtar and Isis share the oldest chthonic myth of the resurrected god, though it’s hard to assess whose version is the oldest (Inanna/Ishtar’s dating from a Sumerian text a couple hundred years younger than the Pyramid Text that is our earliest record of the Osiris myth). In her myth cycle, Ishtar travels to the underworld on her own and her husband, Dumuzid (Tammuz), is sent there as punishment for not mourning her sufficiently while she was gone. But Ishtar has a change of heart and later rescues him, after which Dumuzid spends half the year in heaven and half in the underworld as a gender inversion of the Persephone myth.

Incidentally, the Osiris myth also has ties to the story of Persephone, with Isis filling the itinerant mourner role of Persephone’s mother, Demeter. While the Egyptian goddess searches for the pieces of Osiris’ body scattered by Set, she, too, is taken into a royal household disguised as an old nurse and given the care of an infant prince. As a reward, Isis secretly plans to make the boy immortal, but is discovered prematurely by the queen and Isis, like Demeter, withdraws the gift. The Demeter version of the story was likely influenced by either of the two earlier myths, even if Osiris, unlike Dumuzid or Persephone, is never allowed to leave the Duat.

The Egyptians also likely took to Inanna/Ishtar because they were familiar with her dual roles as a goddess of both love and war, just like Hathor/Sekhmet. Particularly in later years, Hathor and Isis were worshipped almost simultaneously, and their iconography slowly merged together into that of a single sky-mother goddess. Ishtar, too, was just another part of this unification.

But Egypt isn’t the only place where Ishtar’s cult ended up; she is also likely the original form of the Phoenician goddess, Astoreth, another love goddess. Astoreth in turn made her way to Cythera and became the Greek goddess Aphrodite, who is born of the sea (and some severed genitals), rather than of the Olympian gods directly. Aphrodite’s bizarre birth points to her likely roots as an assimilated outsider deity, rather than a truly “native” Greek god. See the similarities between the three goddesses below:

Now, one might look at Aphrodite’s well-known penchant for the war god Ares as another signal of her Ishtarian past, but really the connection is even deeper than that. Because while later Greeks would keep love and war as separate entities, albeit lovers, one of Aphrodite’s oldest cult centers was in martial Sparta, where she was worshipped as Aphrodite Areia (“Warlike”). And if that isn’t convincing enough, almost all of Greece hailed her as Aphrodite Ourania (“Heavenly”), just like Ianna.

And by bringing us up to the Trojan War, we find Inanna’s last big jump away from Mesopotamia. Aphrodite leaves the shores of Illium with her son, Aeneas, and arrives at last in Italy, where she absorbs her colorless Latin counterpart and is reborn as Venus, the Roman goddess of love.

The native Roman gods are distinguished mainly by their total lack anthropomorphism or mythology, having more in common with animistic African deities or Shinto forces than even the bare-bones characterizations of the Egyptian pantheon. Even the vague lares and penates, the most basic Roman household and ancestral spirits, had also been brought over from Troy by Aeneas. Much of what the Romans didn’t borrow directly from the Greeks, they took from the Greek-influenced Etruscans who ruled northern Italy before them, including divination practices like the haruspices, the reading of animal entrails to discern the future.

Like most of the classical civilizations, the Romans generally found the Egyptian gods too weird to adopt.

But as one might predict, Isis was the most successful transplant from Egypt to Rome, either in her traditional form, or as her Hathor-hybrid. In part because she’d arrived long before as late-stage Inanna.

Now Osiris, stuck down in the underworld, was less popular with the Greek Ptolemies and their Roman successors, mostly because they were less obsessed with the afterlife than the Egyptians.

But while Isis or the wayfaring Ishtar might not have been able to bring him back from the lands of the dead, Osiris had spent thousands of years saving himself.

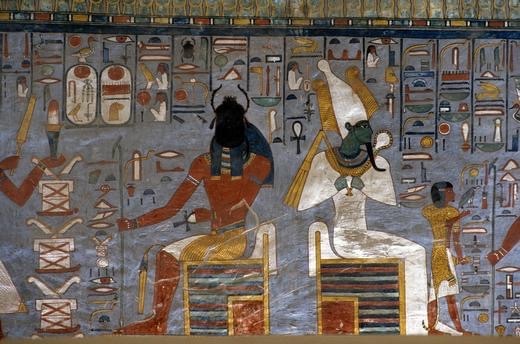

He did this in part by absorbing other gods that helped give him a far greater reach beyond the Duat. Like his wife, Isis, with Sopdet and Hathor, he did this with minor deities like the death god Sokar, all the way up to major, popular gods like the creator god Ptah. The result was a triple deity, Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, particularly in the ancient city of Memphis, where all three gods were powerful.

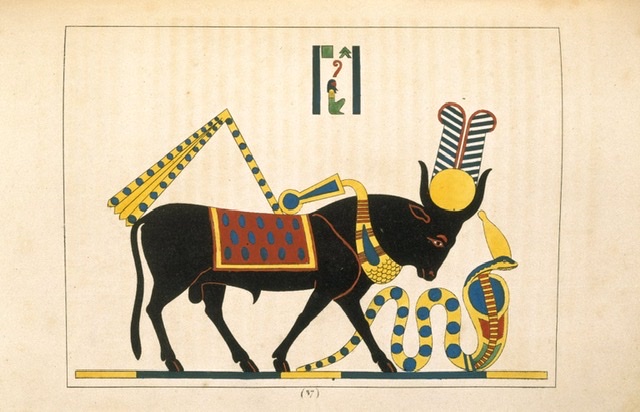

But the other great god Osiris took on was the fertility god Apis, usually depicted as a bull. The son of the cow goddess Hathor, Apis also had a major cult center in Memphis, but eventually his worship became the most popular of several Egyptian bull cults. And that was because he became a symbol of the renewal of life and the land promised by the union of Ptah and Osiris. In life, he was Ptah’s promise of creation, but in his yearly sacrifice, death made him Osorapis, the promise of the dead’s union with the protection of Osiris.

So why am I belaboring this endless compounding of Osiris into a sort of Egyptian Voltron?Because Osiris the Slain God has one more transformation, and it’s the craziest of them all.

When Alexander the Great and Ptolemy Soter arrived in Egypt, they planned to pick a singular deity to represent their new order, as they had in the other kingdoms they conquered. While not particularly interested in foisting their Greek gods on their new subjects, they also had no intention of worshipping Egypt’s ten thousand-strong wacko pantheon. Alexander initially thought to elevate the sun god Amun, but Amun’s cult wasn’t strong enough in the farther-flung Upper Egypt, and if you’re looking for consensus, you can’t afford to alienate the people most likely to revolt against your Alexandrian-based rule.

So Alexander, and later Ptolemy, settled on the broadly popular Osorapis as the official god of the new Greek-Egyptian dynasty. But there was still a problem.

As I said, the Greeks weren’t comfortable with animal gods, but they also thought the mummy-wound Osiris was too dark for their tastes. So Ptolemy took some iconography from the Greek underworld god, Hades, gave him a little bit of Egyptian flair (and Dionysus’ more sunny personality), and voila! The Hellenistic god Serapis was born!

The Ptolemies gave Serapis Isis as his wife and Horus for a son, and his worship went on while the Egyptian Osiris faded into the background. But in his new mask, his cult proved to be extremely durable. Serapis would be adopted by the Romans after the fall of the Ptolemies, who would spread his temples throughout the empire. The Second Triumvirate would build him a sanctuary to share with Isis on the Campus Martius, and the Flavian emperors would depict him on their currency. Serapis’ home base in Alexandria would continue to be a major cult center until nearly 400 AD, when the same kind of Christian mob that murdered Hypatia would destroy his temple and the Nicene-leaning authorities would block its reconstruction.

So there you have it. We’ve seen Inanna become Roman and Osiris became Greek, and Isis become everything in between. Religions evolve and fold into one another when they speak to the universal human condition. Love, conflict, death, grief, hope of a place beyond the world we know, and reunion with those who are gone — these are experiences that transcend time or culture. Early Christianity was successful in these places because it, too, addressed these longings. People of the ancient world could recognize Christ as a compassionate god whose life had began anew many times before.

Leave a comment