When I was doing my circle back to talking about the most important God’s Wife setting, Ombos, last summer, I was aware that I had left an even larger series stone unturned here. One that is particularly egregious considering that three of my six leading ladies are historical figures, and I have long ago done entries for Dru and Theo. So, the wait is finally over and we are doing it: today is the long-overdue deep dive on my first protagonist and best girl, Arsinoë IV of Egypt! We’ll break down what we know, a ton of stuff we don’t, and how I tried to resurrect the most enigmatic of the last Ptolemies into the heroine she’s never gotten to be. But there is a lot of ground to cover (and waaaay too many dudes named Ptolemy), so this is going to be a two-parter. Today, we’ll set up the tangled backstory of Arsinoë’s family and what was happening when she suddenly arrives in the historical record, and next time we’ll see how she meets a true hinge moment in world history! Buckle up, Virginia!

[Arsinoë: Hai, bitches!… can I say ‘bitches’? Me: On this network you can.]

But before we get too deep into the history, I want to mention something about my girl’s name, in part because it’s a question I get asked a lot. Namely (heh), how do you pronounce it? Unfortunately, like most of what we’re going to talk about, it’s complicated. The straightforward answer is that she is culturally Greek and the premodern Greek pronunciation is ar-SIN-o-WEE (like the mythological Cretan queen and Minotaur mom, Pasiphaë). Buuuuuut… the traditional English Classics Department pronunciation is ar-SIN-o-WAY (like the Brontë sisters). Incidentally, this muddle carries over to the Yorkshire girls, too, as their father, Patrick, changed the spelling of their surname from Bronty to the much classier-looking Brontë as a young man. So which is the pronunciation you should go with? In short, whichever of those two that you want. The Greek pronunciation is more “correct,” but classical studies in Europe have a long tradition of bending ancient pronunciation when they want to. Very few people, expert or layperson, call him “Iullius Caesar,” or bother to swap out V’s for W’s as ancient Latin pronunciation would demand (I think because we quietly, collectively decided that “Mount Wesuwius” sounded stupid). And ultimately, that’s kind of how I made my personal ruling: I like the way ar-SIN-o-WAY sounds more, so that’s what I tend to use, and most folks in the know wouldn’t fault you for it. My sister-in-law told me she was watching a Cleopatra documentary where most of the historians were saying it that way, and the one guy trying to be a pedant was clearly struggling to re-train his tongue to the Greek pronunciation. Follow your heart.

[Hopefully my comments won’t be overrun with people who know better than me telling me how wrong I am…]

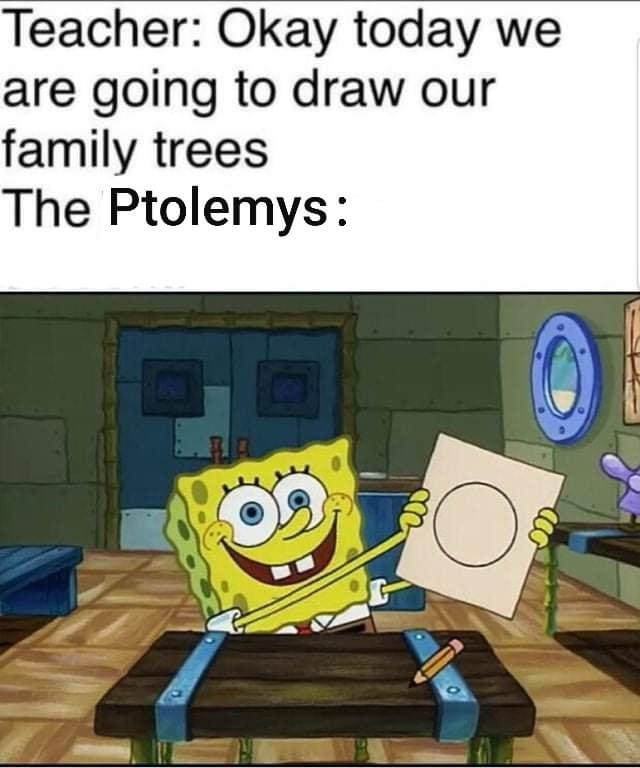

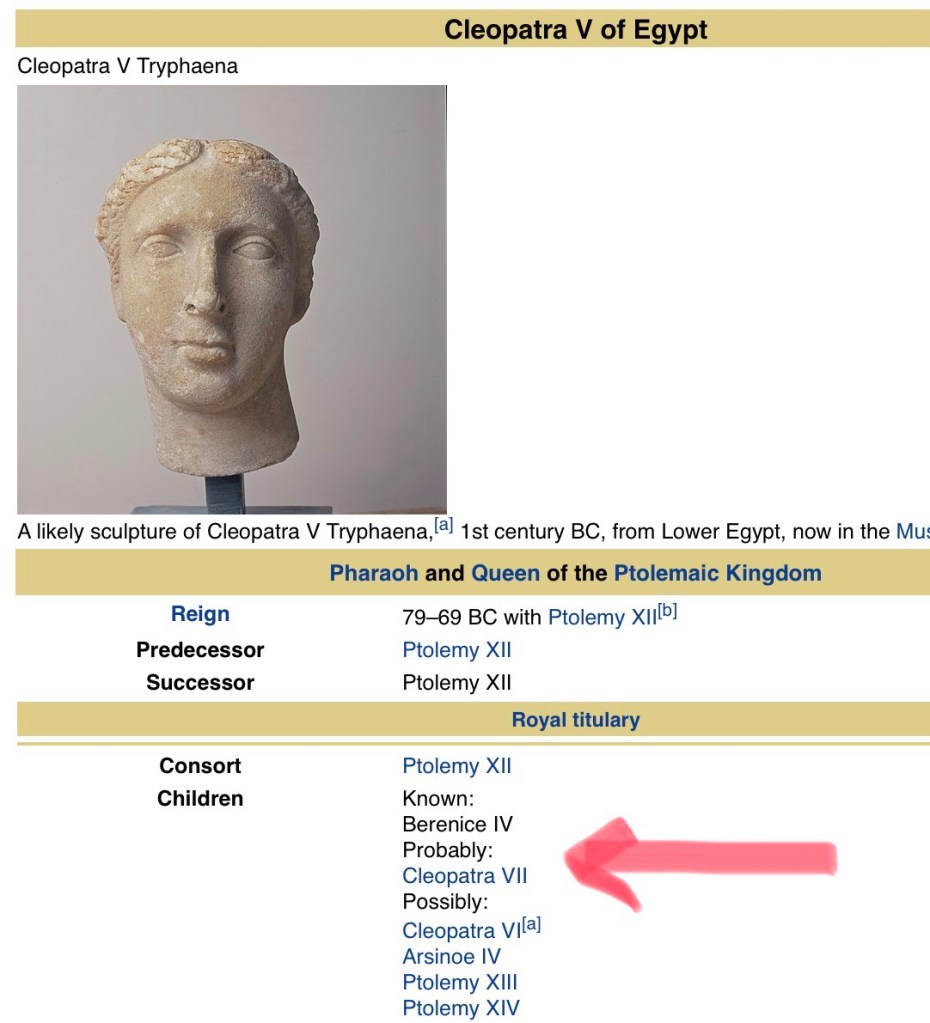

Anyway, as usual, the Ptolemies are trouble right out of the gate, and I can’t even give you a straight answer on Arsinoë’s birth or parentage. The one and only thing that historians ancient and modern can definitively say is that she was the daughter of Ptolemy XII Auletes (c. 117-51 BCE). Traditionally, Ptolemy XII is held to have had only one official queen-consort, his half-sister and/or cousin Cleopatra V (sigh…Ptolemies…), but how many of his five (maybe six) recognized children are her offspring is deeply contested. The only one that is considered in any way certain is that Ptolemy XII’s original heir, Berenice IV, was the daughter of the pharaoh and his queen—everybody else is up for grabs.

Matters are not helped by a serious Cleopatra numbering problem among modern scholars. The Ptolemies themselves didn’t use numerical designations (part of the reason it’s so hard for us in the future to tease them apart), those are a later addition by historians. It is seriously unclear to us if Cleopatra V and the Cleopatra mentioned in contemporary Ptolemaic records with the epithet Tryphaena are the same person, or a (step)mother and daughter. Often they are treated as the same person (aka Cleopatra V Tryphaena, as most royal Ptolemies had epithets), but a sizable minority of scholars think that Tryphaena was a daughter of Cleopatra V and therefore label her Cleopatra VI. This is, with the current available historical record, an unprovable impasse, and so the Cleopatra we all think of when someone says that name, the Cleopatra, skips over all this mess and is denoted by all sides of the debate as Cleopatra VII. My readers know that I chose to make Cleopatra V/VI the same woman—honestly, mostly for simplicity’s sake.

As I said, Cleopatra V is considered the mother of Ptolemy XII’s eldest child, Berenice IV, and Cleopatra Tryphaena, if she’s actually separate person. Cleopatra VII is also usually considered her daughter, in part because it would explain her generally favored heir status with her father, but there is not definitive proof of this. As for the youngest three of Ptolemy XII’s children: Arsinoë, Ptolemy XIII, and Ptolemy XIV, their matrilineage is entirely up for grabs. They may all share a mother who was an unofficial wife or concubine of their father’s, they could all have separate mothers, or they could all even be Cleopatra V/VI’s children—though this is the most unlikely scenario, especially in regards to the youngest, Ptolemy XIV. Although we don’t have a firm birth years for any of Ptolemy XII’s spawn, except for Berenice, who were pretty sure was born in 77 BCE, Arsinoë and Ptolemy XIII are usually thought to be about the same age (with Cleopatra being a little older and Ptolemy XIV a little younger). This is why I depicted them with different mothers, as “twins born in different wombs.” But honestly, there’s an outside chance they could have been literal twins—I wouldn’t even consider that as a possibility, except that twins do tend to run in families and it might explain the otherwise sudden appearance of their sister Cleopatra’s twins with Mark Antony down the line.

Just like their unknown mothers, I do have to mention—as I have in the past—that we also don’t know the exact racial makeup of any of Ptolemy XII’s children. Ptolemy himself was a (deeply inbred) product of a jealously Greek monarchy, but to pretend that the Ptolemies could have never formed non-Greek relationships, especially with non-official wives and concubines, is buying into their propaganda a little too hard, I think. As it is unlikely that any of them would have been fully, racially Egyptian (African), it is almost equally possible that they weren’t entirely Greek. Just as I divide matrilineage in my books as Cleopatra + Ptolemy XIII and Arsinoë + Ptolemy XIV, I make a similar distinction between the first pair being legitimate Greek children, and the latter being illegitimate half-Egyptians; mainly to express the possibility that this could be true of any of them, rather than a statement of historical fact.

We think Arsinoë was born somewhere between 68 and 63 BCE. This conjecture comes from we know her to be younger than her sister Cleopatra (who was born in 70 or 69–and who from here on out we’ll just call ‘Cleopatra’), and, frankly, because nobody believes Arsinoë could have done the things she managed to do while being any younger (which isn’t good science, but what can you do? Astute conjecture rules Ptolemaic studies). As the youngest of three princesses with two brothers, the idea that she would ever be close enough to even get a whiff of the throne of Egypt was extremely far-fetched, so how did she come as close as she did? That is also a frustratingly complicated story.

[Ugggggggghhhhhh…]

Ptolemy XII was not a particularly popular pharaoh during his reign. Granted, by the time he’d clawed his way to the throne, the Ptolemaic dynasty had been in decline for generations, so it’s not like he was given a particularly auspicious place to start. But he was, by all accounts, a typical late Ptolemy: violent, lazy, and dilettantish. Not especially loved in Egypt, he also was struggling with his relations abroad. The kingdom of Egypt was already in a proto-client/satrapy situationship with the Roman Republic by this time—the Roman Senate technically had veto power over which Ptolemy ascended the Egyptian throne. It is believed that as early as his consulship of 59 BCE that Julius Caesar was already tiring of this whole deal and eyeing up simply annexing Egypt to Rome, and Ptolemy XII tried to forestall this by paying huge bribes to the Roman Senate (or really, Julius himself). This stressed an already precarious Egyptian economy struggling with several years of low inundation levels from the annual Nile floods that had in turn led to bad harvests. Caesar took Ptolemy’s money, but then annexed Egypt’s satellite kingdom of Cyprus, ruled by one of Ptolemy’s brothers (also infuriatingly named Ptolemy) anyway. Ptolemy of Cyprus ended his life rather than submit to Roman rule, and Ptolemy XII was widely blamed in Egypt for hanging his brother out to dry. This gave his daughter Berenice and her mother (or sister??) Cleopatra Tryphaena enough momentum to rally the Greek nobility against Ptolemy, and they successfully deposed him in 58 BCE.

In the wake of the coup against him, Ptolemy XII fled Egypt, but not alone. He couldn’t risk taking the most legitimate of his potential heirs, his son Ptolemy XIII, so he settled for his two daughters, Cleopatra and Arsinoë. It’s also possible that he had at least one of his secondary wives/concubines with him, as it is possible that Ptolemy XIV was born while his father was in exile, but the timing on this is unclear. With nowhere else to go, Ptolemy went to Rome to try to raise an army and drum up Senatorial support for his reinstatement. Caesar was probably unenthusiastic, but fortunately for Ptolemy, the big Roman power player in eastern affairs was Julius’ rival, Pompey Magnus, and Pompey was much more willing to honor the legitimacy of Ptolemy’s rule. It also helped that the Greek nobility in Alexandria seemed to quickly sour on Berenice’s queenship. Some of this were things largely out of Berenice’s control, like the still-floundering economy, but she also didn’t help her own case by showing a reluctance to pick a suitable candidate with whom to form a strengthening marital alliance against Rome’s encroachment, and by her execution of Cleopatra Tryphaena in 56 BCE. All of this will give Ptolemy and Rome the wedge their mid-scale military intervention will require, and Ptolemy successfully regains his throne a year later. Berenice is, of course, executed in his wake.

Back in Egypt and without Cleopatra Tryphaena or Berenice to serve as queen consort/co-ruler with him, Ptolemy elevates Cleopatra to this role—one she will hold until Ptolemy’s death four years later in 51 BCE. Now, arguably, Ptolemy could have potentially saved everyone a ton of trouble and simply stated that Cleopatra would continue to rule as pharaoh in his place upon his death, as she was already in position to do so, and at nineteen, a perfectly acceptable age for an ancient monarch. But oh no, Ptolemy had to—bend to Ptolemaic tradition? Exert control over his daughter’s marriage from beyond the grave? Simp for the patriarchy?—and demand that Cleopatra rule jointly with (and marry) her younger brother Ptolemy XIII (age ~12). Ptolemy XII died in March 51 BCE: by August, his kid-heirs were at each other’s throats.

Cleopatra was on the young side, but very much an adult by ancient standards when her father died, but her relative youth combined with her gender hobbled her ability to outflank her teenage brother who was extremely young, but had the good fortune to be a boy. The courtiers who fell into Ptolemy XIII’s faction, led by his eunuch-tutor Pothinus, were able to spin their support for him based on male-preference, as well as the unspoken idea that it would be much easier for all of them to wield more political power with a boy king than the young adult Cleopatra, who had her own ideas. We don’t know anything about Arsinoë’s position in all of this, but, early on, one imagines that she—and her own small contingent led by her eunuch-tutor, Ganymedes—would have likely hung back and attempted to remain as neutral as possible until it was clear which faction was likely to come out on top. As we’ve already seen, the Ptolemies were not squeamish about getting rid of troublesome relatives, so it made sense to keep one’s head down as long as one could.

For a while, Cleopatra was able, through age and probable talent, to gain the upper hand and ostensibly shunt her brother and his posse from any actual power. Egypt was still struggling with a multi-year drought/famine situation, but with virtually sole control of the government, she was at least in a position to stop squabbling with the court and address the kingdom’s actual problems. However, Cleopatra then made a rare miscalculation. After her father’s defeat of his rebels in 55, Rome had kept a contingent military force in Egypt—supposedly to protect the recrowned Ptolemy XII, but more so to protect Rome’s interests in the kingdom. Led by Cicero target, Aulus Gabinius, this force was generally referred to as the Gabiniani. In practice, the Gabiniani’s position in Egypt was complex. Their officers tended to think of themselves as Romans and not really subject to the ruling Ptolemies, while the rank and file soldiers quickly intermarried with the locals of all ethnicities and often became more aligned with Egyptian interests. The real trouble for Cleopatra began when some Gabiniani soldiers got into a fight with the sons of Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, who was serving as the Roman proconsul of Syria. Bibulus had sent his sons to recruit the Gabiniani to help him fight a war against Parthia. The Gabiniani didn’t want to go fight Parthia, so they clashed with Bibulus’ sons—and either deliberately or by accident—killed them.

Bibulus, of course, demanded that the guilty Gabiniani be sent to him in Syria to face prosecution. The Gabiniani, through their general Aulus Gabinius, appealed to Cleopatra and asked her to adjudicate the guilty parties in Egypt (essentially asking her to protect them as her troops). This obviously put Cleopatra in a tough position, but she ultimately decided to put her own allegiance to Rome over the split loyalties of the Gabiniani. She had the guilty soldiers arrested and promptly sent them to Syria for Bibulus to deal with. This shattered whatever support the Gabiniani had for Cleopatra’s rule, and they promptly threw their loyalty behind Ptolemy XIII’s faction. There might have been a time in Egyptian history where losing a force the size of the Gabiniani wouldn’t have sunk a sovereign, but in Cleopatra’s Egypt, the Gabiniani were the best and most highly-trained soldiers in the kingdom. Them not having your back was a disaster. Through sheer force, the Gabiniani were able to reinstate Ptolemy’s joint rule with his sister, and he and Cleopatra were back in an uneasy ruling detente. And that’s when all hell broke loose in Rome.

The start and magnitude of the Roman Civil War between Caesar and Pompey’s factions in 49 BCE blew aside a lot of smaller issues in the wider Roman world. Like, we don’t end up with a real resolution on the Gabiniani/Bibulani situation—Bibulus, clearly afraid to misstep with whatever team was in control of Rome, ended up just sending the Gabiniani soldiers back to Cleopatra, telling her to let the Senate punish them (which by then she probably wasn’t in a position to do, and I doubt that Ptolemy’s pro-Gabiniani people did anything about it). But the volatile situation in Rome probably helped Cleopatra hold onto what power she still had left, as Ptolemy couldn’t risk offing her and potentially pissing off Egypt’s traditional ally, Pompey, who’d supported her rule up until this point. Cleopatra knew that Pompey was her best bet at the outset of the civil war, and demonstrated her loyalty to his cause by making sure that his forces were kept well-supplied with grain. However, this, like with the Gabiniani, is another instance of Cleopatra prioritizing her good relations with Rome over the wider needs of Egypt, which was still in the midst of a famine. Ptolemy’s faction leveraged Egypt’s dissatisfaction with its limited grain stores being gifted abroad to stage a full coup against Cleopatra, and almost exactly a decade after the same was done to her father, she was ousted from the throne, and she had no choice but to flee the kingdom or risk losing her life to her brother’s minions. But just like Ptolemy XII, she wouldn’t leave alone.

It’s unclear if Arsinoë had any more choice to leave Egypt with her sister than she had possessed when her father had taken her with him in 58. Arguably, Cleopatra’s reasoning was little different than Ptolemy XII’s had been: it would have been too risky to try to snatch up Ptolemy XIII’s ostensible heir, their youngest brother Ptolemy XIV, and having another heir of the blood, Arsinoë, was better than nothing. Also, if she had left Arsinoë in Egypt, it would have made Cleopatra vulnerable to Ptolemy’s faction simply replacing her with Arsinoë as queen and cut her out entirely—which would have made it that much more difficult for her to regain her position. And it’s this second, compelling point, that makes me think that Arsinoë was more of a hostage than an ally in her travels with her sister.

Cleopatra first went to Syria, hoping to receive aid from Marcus Bibulus, who owed her a favor after the debacle with the Gabiniani. But by the time she and Arsinoë arrived in Antioch, Bibulus had died and had been replaced by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio(c. 95-46 BCE), who proved to be unwilling to risk his position or his troops for her with Caesar’s legions breathing down his neck. Denied help in Syria, the princesses returned south to Judea, where Cleopatra tried the same plea with Antipater the Idumaean (113/14-43 BCE), who was the dying Jewish Hasmonean dynasty’s consigliere and Rome’s liaison (and the real power in the region). Both Scipio and Antipater were Pompey allies, but neither wanted to make a misstep by propping up a deposed Cleopatra without input from Rome, and with that not forthcoming, Cleopatra was on her own.

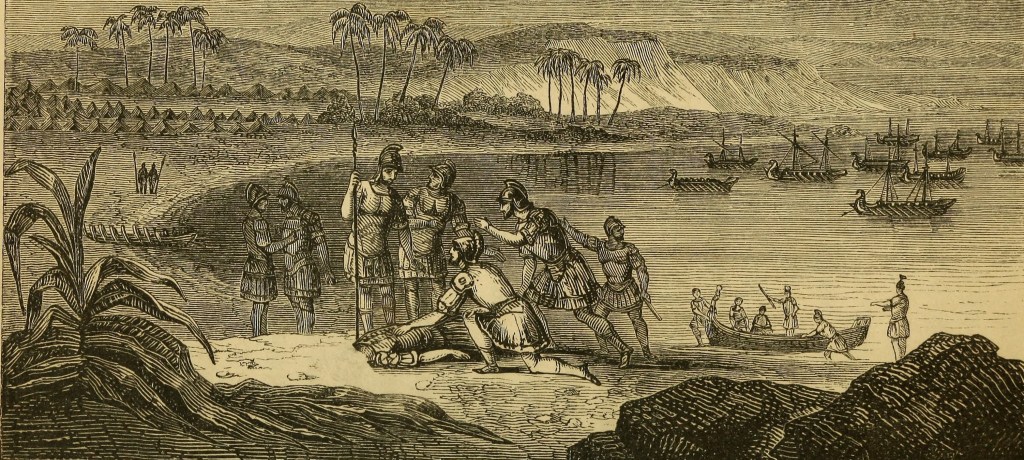

But when all hope for the queen seemed lost, she caught a break. Following his disastrous defeat by Caesar’s forces at the Battle of Pharsalus, her savior Pompey was himself on the run—and decided that his best hope for rallying what remained of his army was to head to Egypt. With the opportunity to plead her case directly to him, Cleopatra packed up her sister and her retinue, and hurried back to Egypt. She reached the outpost port of Pelusium in September of 48 BCE with Pompey’s flotilla bobbing just offshore… and Ptolemy and his retainers on the beach waiting for them both. And it’s unlikely that Cleopatra ever got to speak with Pompey, as the defeated general was murdered by Achillas and Lucius Septimius, two of Ptolemy’s goons, almost the moment he landed. The motivations for the young pharaoh to execute his Roman patron are not entirely clear, but they are typically thought to be that either Ptolemy (read: his tutor Pothinus) thought that Pompey would take over Egypt directly in order to have a new base of operations and Ptolemy would lose his throne; or they thought that Pompey was finished and they hoped to butter up Caesar—when he inevitably arrived on Pompey’s tail—by giving him his enemy already dealt with, and Caesar would side with Ptolemy against Cleopatra in gratitude.

So that’s where we’re going to leave our fractious Ptolemies for this week: Ptolemy and Cleopatra glaring daggers at one another over Pompey’s decapitated corpse and their very much alive sister, Arsinoë, and Caesar’s ships are two days’ out from Alexandria. I know that there wasn’t much Arsinoë in this Arsinoë entry, but we’re getting there. Much like Cotton Eye Joe, y’all need to know where she’s come from to know where she’ll go. Stay tuned!

Leave a comment