Today I thought we’d get a little science-y, and talk about the multifaceted neurological condition synesthesia, which, broadly, involves the conflation of sense stimuli along divergent perception pathways in the brain. Synesthesia is more well known and discussed today than it was in the past, but it’s one of those topics that’s still a little fringe among the general public. This is in part because we still don’t understand a lot about how it works, and also because many of the people who have it still don’t know that it’s a recognized cognitive phenomenon (and not just a weird little thing that they do). I myself didn’t know that I was synesthetic until I was in my mid-twenties, and I don’t think that experience is uncommon—especially for those of us who have one of the rarer iterations of an already unusual condition. Which means that this entry may turn into a PSA for some of you…

So I thought what I’d do here today is do a little rundown on what little we understand of the science behind synesthesia, and some of the main recognized types. And once we’ve laid that groundwork, I’ll use myself as a case study for you all to give you a feel for how it all works (for me, at least), as well as how I use it in my writing. Spoilers: it’s not probably how you’d think.

[Apologies to people in my life who’ve heard me natter on about this before. Blame my mom—she asked me something about my synesthesia recently and got me thinking about it again.]

As I intimated above, synesthesia at its heart is basically experiencing consistent crossed wires among your senses or perceptions in your brain. Sensory inputs that should typically involve only one sense involve two or more—for example, seeing colors when you hear music. While technically a disorder, it’s largely a benign one, and not something to be worried or afraid of, if you experience it. Indeed, some of the types are downright useful in certain circumstances and professions. Synesthetic perception is usually broken down along two main lines: 1) projective, where the individual sees a certain thing; or 2) associative, where the individual has an involuntary connection between sense and a stimulus. A very helpful example given on Wikipedia is that a projective synesthete might hear a particular sound and see, say, an orange triangle, but an associative one will hear a sound and feel that it “sounds orange.” But some people fall in between these two paths, depending on their particular form of synesthesia, or even experience both—just one of the many aspects of the condition that make it extremely difficult to study.

Scientists currently estimate that only about 4% of the global population are synesthetic, but because it is has only begun to come into the general public’s knowledge, although it is still an unusual condition, that is probably a lowball number. For most people, synesthetic pathways appear to be created primarily in childhood, with scientists hypothesizing that the extreme levels of unique information processing that infants and children go through in their early years sometimes lead to this neurological conflation as a way of organizing sensory inputs faster or in what the child perceives as a more ordered fashion. But there are also numerous instances of synesthesias developing in adults after brain injuries, and it’s these individuals who are the ones whom neuroscientists can use to trace and identify how these connections might be made in the brain on a physiological level. Unfortunately, there are limits to this, as most of the data merely confirms that, say, if you are experiencing a synesthesia that involves a visual and auditory component, both of the parts of the brain that process those inputs will light up in a scan.

[This is a brain scan from a 2001 study of someone with grapheme–color synesthesia, with the areas of the visual cortex that we think are affected highlighted in green and red (Ramachandran and Hubbard, 2001). But even this is a proposed visualization, and not specific evidence of synesthetic activity.]

A lot of the studies of synesthesia involve grapheme–color synesthetes because they are among the most common type. Simply put, grapheme–color synesthesia is perceiving letters or numbers as being certain colors (four being green as an example I used in my entry title). Some argue that this larger synesthesia is actually two separate types, divided along how the perception originates: as in whether the perception originates with the letter or number, which would make it more of a conceptual construct (what they like to term “ideasthesia”) than if it originates from the color or sound. As a non-scientist, I don’t particularly care, so as far as I’m concerned, you grapheme–color folks can identify however you’d like. G-C synesthetes tend to have their own unique color associations, but there have been some neuroscientists specializing in early childhood development that have suggested many G-Cs form these connections as they build knowledge bases in different areas through a form of word association. Like, for many (though not all), the letter B is blue because ‘blue’ might be one of the first ‘B’ words a child learns. Some researchers have even suggested that the proliferation of those colored alphabet refrigerator magnets in the western world triggered synesthesia in some children, although this is basically unprovable (though it does make some sense to me for reasons I’ll get into later). Neither of these hypotheses are to suggest that the synesthesia of people who developed it from those sources aren’t real or somehow “lesser than.” How we perceive the world around us is largely environmental, and if someone else’s synesthesia seems to come “purely” from within their head, it’s more likely that we or they just haven’t been able to trace the connections origins yet, as opposed to they “just” thought it up on their own.

[There may be a genetic component to synesthesia, as it can run in families and is often shared among monozygotic (identical) twins, but we don’t even have the whiff of where such a connection might reside within our gene sequence.]

This vague defensiveness on the part of some synethetes is, in my opinion, fueled by a lot of synesthesia’s perception as a specific sign of intelligence and creativity—desirable attributes that one sort of instinctually wants to assign to some special ability to see/feel what others can’t, and not because you imprinted on some fridge magnets when you were three. It isn’t helped that one of the other more common types, chromesthesia (which I alluded to earlier, associating sounds and colors), is understandably well-represented among famous musicians and composers, which lends to that special genius feel of the condition. I personally don’t feel this way, though. I think synesthesia can point to a kind of useful neuroplasticity in its people, but not necessarily a sign of particular ability or intelligence on its own. Speaking of neuroplasticity, I’m sure it’s not shocking to hear that many studies have shown a correlation between synesthesia and neurodivergent conditions like autism. As someone who has never been diagnosed, but has many distinctly autistic and ADHD markers, I’m much more willing to bet that my synesthesia stems from plain ol’ neuroatypicality than it does from some mark of superior intellect. For years, it just made me feel crazy, not special.

So what is my synesthesia, you ask? True to form, I couldn’t have even one the relatively “normal” synesthesias, I have to have one of the ones that’s weird even among synethetes. I have lexical-gustatory synesthesia, where I experience the sensation of taste when I hear or speak certain words. And to be clear, I don’t mean that when I hear the word “hamburger” that I can taste a phantom hamburger in my mouth—I can do that, but I bet that you can, too (at least those of you who eat hamburgers). I mean that the word “language” tastes doughy to me and it makes my tongue and cheeks react like I have a mouthful of bread. L-G synethetes make up only about 0.2% of the total synesthetic population, so there is less research on us in an already niche field of study, and even if there were more of us, I think that we’re just harder to study. With grapheme–color synethetes, there are a finite amount of letters in the alphabet and single digit numbers to report/study, but the boundaries of lexical-gustatory synesthesia are theoretically almost infinite, even if in practice I think there tend to be neurological limits.

Based on my personal experience, I think, like the grapheme–color synethetes, we form most of our connections in early childhood, which in turn tends to mean that the words we can taste are limited to the vocabulary we possess at that time. Some researchers have thrown out the age of nine as roughly the boundary for when most children stop making these sorts of neural connections, and that feels about right to me. I almost entirely don’t have this sensory input for words I learned in high school or adulthood (I have one exception to this, but I have a theory for why it broke through that I’ll get to in a minute). Similarly, and corroborating this theory, the majority of my connections are linked to foods I ate as child and not the much wider palette I have as an adult. Many of my L-G words are bready or meaty, with only a couple of basic fruits or vegetables. No coffee or red wine… nor flavor profiles that come from less Americanized foods. Which suggests that someone with L-G who was raised in, say, Korea, would probably have a vastly different experience of the condition than I do.

I also think that the younger I was when I first heard/read the word, the stronger the L-G connection is. Because some of “my” words trigger my response more strongly than others. Like all synesthesias, a lot of the testing that researchers are doing on lexical-gustatory synesthesia is focused on consistency to combat the fact that so much of the research by necessity rests on self-reporting. As in, do you always say that Word X tastes like Y, even when asked years apart. As I said, when I first heard of L-G synesthesia, I was in my mid-twenties, and for a couple of years, I tried to keep a running list of the words I could taste, and even though I was a loquacious child with a fairly extensive vocabulary, I’ve only ever recalled around thirty words that trigger this physiological/sensory response. And even a few of those, looking back on, I think are dubious, as in, I don’t know if they would hold up if I was asked about them, now fifteen years later, under anything approaching laboratory conditions.

For the record, I think overall that this is a good thing. It can be distracting enough when my “stronger” words trigger the response—I can’t imagine being able to concentrate if I was having this reaction to hundreds, or god forbid, thousands of words. This also feels like it aligns with the “capacity” expressed by the more common synesthesias (what with twenty-six letters in the Romanized alphabet, etc). Without some guardrails like that, it feels like the neural pathways in the brain would simply overload, rather than form these symbiotic connections. I should also point out that it is possible that L-G synesthesia might fade in some amounts over time. While the words I remember are as strong as ever, it’s possible that I experienced the overlap more intensely when I was younger (particularly when you take into account that the triggers words would have made up a larger percentage of my total vocabulary). But whether this is a sign of neurological aging, or that, frankly, I know so many words now that the sum total has somewhat drowned out what was more intense in my youth, I couldn’t say. It’s also possible that living with it for so long and consciously forcing it into the background (because what do you mean you taste words?? Weird!) for half my life has lessened its overall effect on my present mind. Hard to say.

Looking at my list from circa 2008, I can say that, for my particular lexical-gustatory synesthesia, the words whose connections I can in any way trace operate in two distinct ways. One, we have a handful of what I’d deem “fridge magnet” words, that is, non-food words I know developed their tastes from associations on common food packaging from my childhood. Three of these words are probably among my strongest triggers: English, ocean, and cup. ‘English’ is the most basic: we ate a lot of English muffins when I was young, and I clearly imprinted on the standalone word to always taste like them, whether I was talking about the English Revolution or the actual bread product. ‘Ocean’ is more corporate and potentially embarrassing: I also drank a lot of cranberry juice as a child and very specifically Ocean Spray brand, so now ‘ocean’ causes my whole mouth to react like I have the tart sweetness of cranberry in it. ‘Cup’ is the most specific and strange: a typical American child spends a lot of their childhood mornings staring at the breakfast cereal box in front of them, and one of the cereals in heavy rotation in our house were Frosted Mini Wheats (bite-sized shredded wheat with a sugar layer on one side of the wheat bale). During what I’m guessing was that crucial 5-9 year old age range, Kellogg’s did a ton of cross promotion on their cereals with FIFA trying to get American kids hype about the World Cup… and now all I can taste is shredded wheat.

[Where’s my FIFA peace prize for that???]

Most of the rest of my words I can suss out in any way fall into what researchers have identified as a kind of cross-phonological phenomenon within L-G synesthesia, where non-food words that produce similar sounds to food words get free-associated in the person’s mind. In practice, it operates on almost the same principles as Cockney rhyming slang—which is either interesting or funny, depending how you look at it. A good example of this from my bank is ‘oak’, which I think my brain links to ‘yolk’, so the result is ‘oak’ tastes like eggs. A less straightforward example is ‘cook’, which I think is linking specifically to ‘soup’, and therefore tastes brothy. Another that has a kind of circuitous logic to it is ‘flop’, which I think I’m linking to pancakes through “flapjack”, but ‘flop’, as a linguistic inverse of ‘flap’, tastes more strongly of pancakes than the much more direct ‘flap’ does. And ‘flip’ is neutral/no taste. So, you see how even when it sort of makes sense, it barely makes any sense.

[That single word that I can think of with a taste that I learned past late childhood is ‘exculpatory’ (you can really tell I was in law school), but I’m pretty sure we’re dealing with another phonological free association because it tastes like scalloped potatoes (potatoes au gratin), and my brain is latching on the similar sounds of exculpatory and scalloped.]

By now you’ve probably figured out that despite being a lexicon-based condition, lexical-gustatory synesthesia doesn’t really “help” me with my writing much. Part of this is because of mine’s limited vocabulary, and the rest is because it’s, as I mentioned, kind of distracting. Not the tastes themselves, being foods that I generally like, but the false feel of them in my mouth, that my mouth and tongue are “active” even though I’m not eating, is sometimes annoying. On the other hand, I don’t know if my synesthesia has affected the way I have acquired language throughout my life and has indirectly fueled my high-verbal/high-reading metrics. The tendency to free associate among non-related words in a semi-unconscious way suggests yes, but I have no hard data to back that up.

But I am interested in the mechanics of my synesthesia and the ones that don’t have, so that much has crept into my writing. Currently, I have two openly synesthetic characters across my books, both God’s Wife characters (though, being from the past, neither of them calls themselves that). Drusilla from Children of Actium has a form of the aforementioned chromesthesia, in that she hears people’s voices in different colors, and as no two people have exactly the same voice, everyone’s “color” is a slightly different shade. Dru also experiences a modified grapheme–color synesthesia that derives from this, where something written by a person takes on the color of their voice because of her visualizing them speaking their words aloud to her. The other character is Balbillus from Daughter of Scorpions, who has ordinal-linguistic personification synesthesia, where numbers, months, names, and other similar inanimate entities take on genders and/or specific personalities. Dru’s synesthesia is very vibes-based, but her colors don’t always correlate to a person’s personality, but for Balbillus, his synesthesia is a direct interpretive tool he uses to understand his astrological calculations.

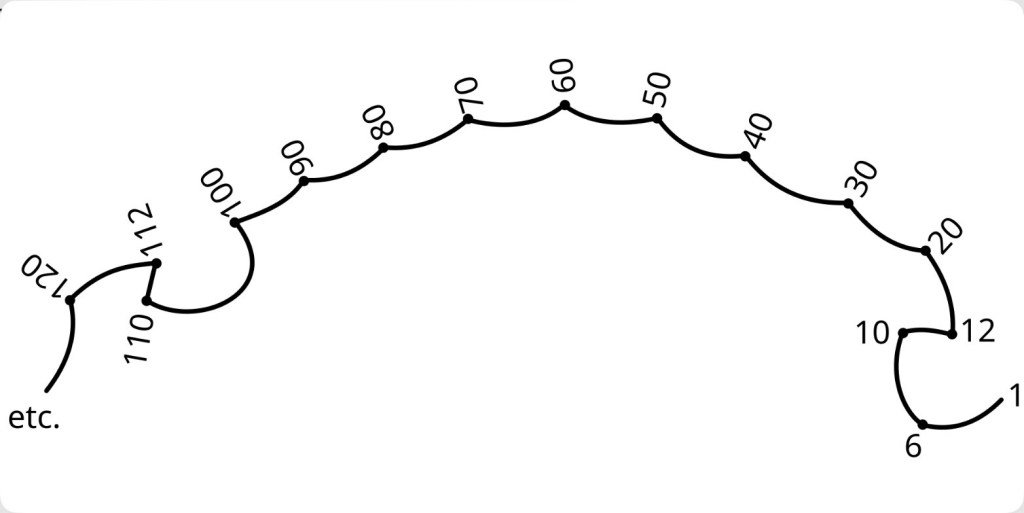

But this is an interesting bit of character depth building that I think is a great way to add to people in your narratives. Though, as I alluded to earlier, consistency is a big part of real world synesthesia, and adding a character like this to your story is one of the few times that I seriously recommend some form of character sheet. Somewhere in my notes I have a master document for Dru that lists all the other characters in CoA and what color their voices are to her, whether it’s ever directly mentioned or not. This was in part so I had it all mapped out in case I needed them, as well as to make sure I never accidentally reused a specific color. If you have a character with, say, grapheme–color synesthesia, you’d probably want to list out all the alphabet letters and at least all of the single digit numbers for them somewhere, just so you can keep it all straight. These synesthesias are likely the most straightforward to write as an outsider author/narrator, but there are others if you like a challenge. Be more adventurous than me and try to pin down a lexical-gustatory synesthete! Do your own take on spatial sequence synesthesia, the memory palace people who see abstract concepts like time and musical notation as visual phenomena they can interact with! Or mirror-touch synthetes, who can physically feel things happening to other people in front of them! The brain is a wild, wacky place, and its ability to forge unlikely connections is almost unquantifiable. Don’t be afraid to explore!

[Number form synesthesia like this, where the synesthete has a concrete, personalized mental map of numbers as they hear them, might as well be Greek to my ballistic-verbal brain, but I’m sure it makes perfect sense to them.]

Leave a comment