We’ve made it, folks! After years of dragging my feet, I am done with the entirety of Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia, and I’m here to give you a slightly unserious summary of the last ten books! In true wrap-up fashion, Pliny is presenting us with his final pharmacological thoughts, some miscellaneous facts about water and aquatic life that got missed in the earlier zoology books, and finishing up with a bird’s eye view of ancient geology. Oh, and because this is ancient science, we also get some straight up magic—oOoOo! So let’s get into it!

[And here are links to Books 1-11 and 12-27, if you need to catch up]

In Book XXVIII, we’re still dealing with medicine, but Pliny has mercifully moved on to non-plant-based remedies. But before he gets too deep in the (again, mercifully metaphorical) weeds about this, in what will be a recurring storyline through the last pharmacology books, he begins with a long rant about the Persian magi and how they are shameless, wicked liars who are not to be trusted. I made a joke at the start about ancient magic masquerading as science, but truthfully, Pliny has a very dim view of the supernatural and those who claim to be able to control it. He might get his scientific causations wrong, but rarely is he a champion of straight up sorcery. His common sense instincts tell him that incantations and other magical formulae are probably bunk, but he acknowledges that belief in such practices is an intricate part of the Roman religious sacrifices of his time and complicates a hard negative from him here (XXVIII, iii.10-13). And this is an example of Pliny at his most interesting: he often has surprisingly modern views of the natural world, but he is also, like the best scientists, slow to dismiss things he can’t understand out of hand, indirectly bowing to concepts like the placebo effect, even though he doesn’t know what that is. In a similar vein, he unsure about the efficacy of curses, admitting that people might just be freaked out by unknown foreign words, or simply unfamiliar Latin ones (XXVIII, iv.20), and starting at (XXVIII, v), he gives an exhaustive list of Roman superstitions, most of which he seems to find silly. But, as said, he has no time for the magi and their foreign nonsense when there’s plenty of that to go around at home already.

Once we get into the nitty gritty of the book, he also deplores the idea of most human-based remedies, especially if they involve the blood/viscera or death of the donor person: “And by Heaven!, well deserved is the disappointment if these remedies prove of no avail. To look at human entrails is considered sin; what must it be to eat them?” (XXVIII, ii.5-6). As an example, he cites a dubious epilepsy remedy involving a gladiator’s blood (XXVIII, ii.4). Pliny does however allow for use of human breast milk, saliva, or living human contact in medicine (remember the prescription from last entry about healing abscesses with a live, naked girl?)(XXVIII, ii.8-9). Indeed, he suggests saliva for a dizzying array of conditions including snakebites, epileptic fits, offending the gods (spit on your own bosom), spitting 3x on the ground to seal a ritual, spitting on your palm that hit someone to lessen their offense, spitting in your ear to chase out an insect in there, spitting on your right shoe before putting it on or passing a dangerous place, (XXVIII, vii.35-39). It is here, twenty-one books later, where it suddenly becomes apparent why it was worth noting that Antonia Minor was praised for never having been seen to spit in public (VII, xix.80)… Pliny also notes that several “very famous authorities” claim that semen is an effective antidote to scorpion stings, but before y’all test that one out at your next sex party, he assures us that they are, in fact , incorrect about that (XXVIII, xiii.52). But for the ladies, know that your menstrual blood can chase away storms (XXVIII, xxiii, 77), but you should probably decline any offers from farmers to send you naked into their fields while on your period to kill vermin, especially not at sunrise (XXVIII, xxiii.78). And after all the advice about what to do with your spit and menstrual blood has turned you off a bit, Pliny comes back and recognizes that the best remedies are often the classics: a plainer diet, walking/exercise, sleep, massage, or a change of environment (XXVIII, xiv.53-4).

This book ends with the start of Pliny’s look animal-based remedies, mainly those procured from domestic or semi-domestic animals. Though, he does go off on a tangent about women not having to worry about miscarriages if they wear a strip of hyena breast, seven hyena hairs, and a stag penis wrapped in a gazelle leather pouch XXVIII, xxvii.98-9)… presumably because none of them will ever be close enough to a man to get pregnant with that accessory… But if your stag penis-hyena amulet is scaring the gents away, Pliny offers up a recipe of jellied white bull calf pastern bone as a skin whiter/wrinkle remover to try to bring them back (“a trifle…to satisfy the women”, he coos modestly to himself…) (XXVIII, l.184). But just in case you think it’s only the ladies doing gross stuff with animal bits, he also talks about Nero drinking a concoction of goat’s dung (dried, powdered), vinegar, and honey, which was supposed to protect him during falls from chariots (XXVIII, lxxii.238). Though, hands down, the best remedy Pliny mentions in this book is the one about having an elephant touch your head with its trunk to cure headaches (XXVIII, xxiv.88). I’d imagine having an elephant touch me with its trunk would fix everything with me🥰

Book XXIX is still talking about animal product remedies, ones he classifies as “neither tame nor wild,” but Pliny starts off with a quick history of doctors, mostly focused on Greek personages, and notes that most doctors in Rome are still Greeks in his time. But unlike, say, traditionalists like Cato the Elder, Pliny is willing to defend the use of “foreign” medicine among Romans (XXIX, viii.20). This is another book where you get a real feel for the types of ailments that preoccupied Romans most, with eye and skin conditions, baldness, snake bites, and dog bites being the major players. One remedy the Romans were partial to was using wool medicinally, considering it to have supernatural powers (XXIX, ix.29-32)—even better if you can get it with the sheep sweat (oesypum, suint) under it (XXIX, x.35). Pliny notes that wool has an affinity for eggs and egg-based medicinal ingredients (XIX, xi.39), eggs being, like animal greases, used for almost everything at least as a prescription base or binding agent. But you might need the much more exotic dragon blood to fight a snake bite (the Loeb translators suggest that “dragon” might be pythons or another large nonvenomous snake) (XXIX, xx.67-8; note b). Speaking of snakes, Pliny sees vultures and serpents in opposition—which only interested me as it might be an instance of a Roman mind applied to what Egyptians saw as a balance (Wadjet and Nekhbet)(XXIX, xxiv.77).

Book XXX is still more animal-based illnesses and remedies, as well as circling back to magic, though with that last one Pliny threatens that he will continue to expose the lies of the magi whether we like it or not (XXX, i.1). Part of his evidence for his disbelief is that even Nero thought that magic was fraudulent, and that little shit would believe anything (XXX, v). Anything that even approaches “real magic” for Pliny comes from the Persians (specifically Zoroaster and his adherents), and the Thessalians considered the magicians par excellence (XXX, i-ii), but raises his eyebrow at wild claims they make, like that the gods refuse to listen or appear to those with freckles (XXX, vi.16).

Once he’s done with the latest magi diss track, Pliny settles back down into his animal remedies again, throwing out a personal suggestion of kissing a mule’s muzzle to cure a bad cold (XXX, xi.31). He also says that his favorite stomach remedy is eating grilled African snails in a wine and garum sauce, though he does warn that your breath will be atomic (XXX, xv.44). Pliny loves snails as medicine the way Cato loves cabbage. This book has a ton more honey-based medicines, but here most of them come from the honey of specifically dead bees, which is rather macabre, as are the multitudinous cures involving wearing dead animals or dead animal parts. There’s an Ovid remedy for quinsy (tonsillitis) involving swallow ash in hot water (XXX, xii.33), and a weird anecdote about two Asprenas brothers who cured their colic: one by eating a lark and wearing its heart in a gold bracelet; and the other by performing an unspecified sacrifice in a shrine of unbaked bricks built in the shape of an oven that was blocked up when the ritual was complete (XXX, xx.63). But if all else fails, you can always use bats’ blood as a depilatory (XXX, xlvi.132)—explaining why everyone was always looking for rabies medicines in the ancient world.

Book XXXI moves into aquatic animal medicine and water-based cures. The latter focus a lot on various hot springs, including one, the Posidian, at Baiae that is supposedly hot enough to cook meat in (XXXI, ii.5), and other less specific springs that do things like make you hate wine and another that conversely gets you drunk (XXXI, xiii.16). Pliny gives a lot of space to sussing out what makes clean water—a consuming concern of ancient people (XXXI, xxii-xxiii)—while demonstrating that Romans had a basic knowledge such as running water is healthier than stagnant water (XXXI, xxi.31) and that boiling water makes it safe to drink (XXXI, xxiii.40). They also understood that poisonous gases can be released while digging wells, and knew in those circumstances to use a lamp to test for gaseous matter (XXXI, xxviii.49).

But the main event of this book is the infamous garum digressions (XXXI, xliii): how to make it and what to use it for. Aside from its culinary uses, Romans also deployed fish sauce as a treatment for burns, ulcers, dog bites, and crocodile bites. Pliny makes special mention of it as a cure for mouth sores (XXXI, xliv.97), which honestly tracks as the salt in garum probably functioned similarly to modern salt water rinses commonly recommended for oral wounds. Though, with a higher likelihood of fishy breath. Additionally, he mentions that Romans knew that natural sponges are absorbent and used them as surgery swabs (XXXI, xlvii.126).

Book XXXII is the so-called Index of Fish, though one should be aware that “fish” for Pliny includes fish, turtles, crabs, dolphins, seals, beavers, some snakes, and frogs—basically anything that is semi-aquatic or amphibious. He calls fish “the greatest of Nature’s works”, because fish can live in an environment as chaotic as the sea with little difficulty. He also claims that they have the power to halt battleships—something that supposedly contributed to Mark Antony’s bad times at the Battle of Actium (XXXII, i.1-3)—and swordfish, presumably very large ones, that can pierce and sink ships (XXXII, vi.15). He quotes Juba as saying that there have been whales 600ft long, and Pliny claims that Ovid was supposedly working on a book about fishing (Halieuticon) (XXXII, v.11-13) during his exile at Tomis (XXXII, liv.152) that he sadly never got to finish, even if I suspect that, to paraphrase the Onion, that “Man’s Relationship Advice Same as His Fishing Tips.”

Pliny’s section on beavers appears to be another source for tropes that come up in later medieval bestiaries, particularly the myth that beaver testicles are considered valuable and the animals will bite them off to escape hunters. Though, according to him, the real beaver oil comes from the animal’s kidneys and the testicles bit is just a ruse (XXXII, xiii.26-28). Additionally, rinsing your mouth with turtle blood three times a year makes you immune to toothaches (XXXII, xiv.37), and if you put the extracted tongue of a living frog on the heart of a sleeping woman, she will answer all questions truthfully (XXXII, xviii.49)—though she will probably have a few questions of her own for you (like why the hell you’re putting severed frog tongues on her while she sleeps). Speaking of frogs, Pliny calls angler-fish “sea frogs,” and says that if they are boiled in wine and vinegar, they can counteract poisons (XXXII, xviii.49), but the astrologer Thrasyllus suggests crabs for snake bites (XXXII, XIX.55). But this book winds up with the truly bold claim that while we don’t know the names/quantity of all land animals, “we” already know all sea creatures (XXXII, liii.143).

Book XXXIII is where Pliny is finally rounding the final turn on his magnum opus subject-wise, and whereas as we started in the stars, we will end beneath the earth with metals, minerals, and their adjacent human uses. In this book, he primarily focuses on gold and silver, along with electrum (an alloy of the two), cinnabar, and ochre. Pliny agrees that many of the metals and minerals he will discuss can be useful, he ultimately feels that the things they drive humanity to do as sources of greed and violence outweighs those benefits: “We trace out all the fibres of the earth, and live above the hollows we have made in her, marveling that occasionally she gapes open or begins to tremble—as if forsooth it were not possible that this may be an expression of the indignation of our holy parent! We penetrate her inner parts and seek for riches in the abode of the spirits of the departed, as hough the part where we tread upon her were not sufficiently bounteous and fertile…The things that she has concealed and hidden under-ground, those that do not quickly come to birth, are the things that destroy us…” (XXXIII, i.1-3)

Principle objections out if the way, Pliny has a long digression about rings, even though they were not historically a common piece of Roman jewelry, especially anything beyond the traditional iron rings used by far ancient officials and as bands by wedding couples (XXXIII, iv.12). As a result, he is generally (as usual) suspicious of more elaborate rings as an expensive and superfluous luxury. Accustomed to them in his own time, Romans of all genders tended to wear multiple rings on their fingers, except for the middle finger, which was always kept bare (XXXIII, vi.25). As emperor, Claudius instituted a rule that anyone wearing a ring with his portrait was given free access to him, which must have eventually gotten extremely out of hand as a tradition because Vespasian would abolish the practice when he assumed the throne (XXXIII, xii.41). Pliny goes on to blame the Celts for the fad of wearing bracelets (“Dardania”) in Rome, and the Egyptians for basically everything else jewelry-related, including men—gasp—wearing Harpocrates rings (XXXIII, xii.40-41).

Proving that nicknames for coinage are timeless, he also the names of two early silver denarii were “pair of horses” and “four in hand” based on their designs with a bigae and a quadriga chariot, respectively (XXXIII, xiii.46), before going on about Mark Antony having a bunch of golden toilets for “satisfying all the indecent necessities”, something Pliny claims even Cleopatra probably found a bit over the top (XXXIII, xiv.50). He reports that Julius Caesar had the gladiators fight with silver weapons at the funeral games of his father, that Nero once covered the entire Theater of Pompey in gold to impress/intimate Tiridates of Armenia, and that Agrippina the Younger once wore a military-style cloak to a naumachia made entirely out of woven gold (XXXIII, xvi.53-4; xix.63). He also describes a goblet in a temple of Athena on Rhodes that was dedicated to the goddess by Helen that had the same dimensions as one of her breasts (like the apocryphal claim that champagne coupes are modeled on Marie Antoinette’s) (XXXIII, xxiii.81). But as to whether any of these stories are true, Pliny merely notes that “We too have done things to be deemed mythical by those who come after us.” (XXXIII, xvi.53)

As I said earlier, in addition to gold, Pliny touches on silver and cinnabar, the latter used in paintings and for certain religious rituals such as painting the bodies of those in a triumph (cf. the show Rome), though he confesses that he doesn’t know the origin of this tradition (XXXIII,xxxvi.111-2) and is aware that cinnabar is potentially poisonous (XXXIII, xl.122). He also claims that Egyptians stain silver to scry into in order to see Anubis (XXXIII, xlvi.131), and thinks that “Egyptian blue” is made of ground azurite (XXXIII, lvii.162). This is a good hypothesis as azurite is copper-based, but its formula is Cu3(CO3)2(OH)2, and we now think that Egyptian blue is calcium copper silicate (CaCuSi4O10) or CaOCuO(SiO2)4–calcium copper tetrasilicate. Either way, Pliny states that he has done the best that he can when stating various metal costs and commodities rates, but since all of these fluctuate by year, market location, and vendor, he does not want to hear about any potential discrepancies from anyone (XXXIII, lvii.164).

Book XXXIV continues the copper-based discussions of the last, while adding in the copper alloys bronze and brass, as well as iron and lead. Naturally-occurring copper ore and metallic copper were actually not common in the Old World, but in order to manufacture bronze (copper/tin), the ancient Mediterranean was actually quite adept at artificially producing copper ores by heating more plentiful copper oxides, silicates, sulphides, and carbonates (XXXIV, n.a (p.126)), with the most valued bronze comes from Corinth (XXXIV, iii.6-7)

Most of this book is tied up with bronze as it related to ancient sculptors and sculptures. Pliny describes a fad for bronze art made of copper with silver and gold mixed in, but the craftsmanship behind it was being lost in his time, and he doubts that the art produced was ever worth the additional expense anyway (XXXIV, iii.5). He mentions a bronze statue of Apollo by the famous sculptor Myron (5th century BCE) that was taken by Antony from the temple of Artemis in Ephesus, but later restored by Octavius because of a warning that he received from the god in a dream (XXXIV, xix.58). He tells of Marcus Agrippa donating a sculpture of a man using a body-scraper (a type of sculpture known as an Apoxyomenos) by the sculptor Lysippus of Sicyon for the entrance of his baths that everyone was crazy about, apparently. It was supposedly so good that Tiberius, himself an sculpture connoisseur, couldn’t resist and commandeered it for his bedroom until the public outcry made him return it. Like, they were literally shouting “give us back the Apoxyomenos!” at him in the theaters (XXXIV, xix.61-3). After an exhaustive list of bronze sculptors and their most famous works, Pliny falls back into his medical advice and suggests blowing cuprous oxide into the ear with a tube for hearing loss, or applying it directly with honey for tonsil swelling. Copper and cuprous oxide do have anti-fungal properties, so it might have done something (XXXIV, xxv.109). He is also slapping verdigris (copper acetic acid salts) on everything, and despite its moderate toxicity, it would continue to be used in medicine at least through the 18th century, where according to Wikipedia, it was a treatment for canker sores (XXXIV, XVII.114-5). Pliny rounds things up by suggesting iron on wool to stop menstrual discharges (XXXIV, xlv.153), though I doubt many of your vagina-havers are super stoked to try what is essentially an ancient steel wool tampon.

Book XXXV is devoted to painting, pigments, clay, the pottery arts, and plastering—which might feel left-field in a geology section, but it makes some logical sense as ancient paint pigments are almost universally derived from mineral powders. Pliny thinks that painting began as a monochromatic art, but archeological evidence actually shows that this wasn’t the case (XXXV, xi.29; n. a, p. 282). He laments that painting has largely been ousted by marble work, gold work, and mosaics, with traditional portrait painting being basically extinct as the more realistic style of Roman facial representation was replaced by the best idealized portraits money can buy: “…they leave behind portraits that represent their money, not themselves” (XXXV, i-ii.2-5). Basically ancient photoshop. This obsession with idealization had even led to family wax imagines being less made than in the past (XXXV, ii.6). He tells of Nero having a 120ft-high portrait of himself painted on linen, which was displayed in the Gardens of Maius, where it was promptly struck by lightning and burned down (XXXV, xxxiii.51-2), illustrating one of the many reasons ancient paintings rarely survive into the modern age.

Like with the bronze sculptors, Pliny rattles off a lengthy list of the most famous painters in antiquity, and like with the list of famous doctors, they are almost all Greek. He believes that the model for Apelles’ Aphrodite Anadyomene was of Alexander’s mistresses, Paneaspe, who was given to the painter when he fell in love with her during the painting process (XXXV, xxxvi.86-7). He also thinks that the clay artist who modeled the Venus Genetrix in Caesar’s temple was named Arcesilaus (XXXV, xlv.155-6), and at one point I think that he is trying to describe the Egyptians doing a form of batik painting (XXXV, xlii.150), but it’s not entirely clear. But either way, Pliny is far from a snob, and he includes humble brick making among the more beaux arts mentioned in this book (XXXV, xlii-l.170-4).

Book XXXVI, the penultimate book, is primarily concerned with marble and other rocks, which Pliny considers Nature having created for the sake of creating: “For everything that we have investigated up to the present volume may be deemed to have been created for the benefit of mankind. Mountains, however, were made by Nature for herself” (XXXVI, i.1). As for mankind, like with gold, he considers marble to be a decidedly mixed blessing. Augustus may have made Rome a city of marble, but Pliny doesn’t exactly approve of it. Carian marble was as highly regarded in Pliny’s time as ours, and he credits Caria with the invention of thin-cut slabs (XXXVI, vi.47). He thinks sand from Ethiopia is best for cutting marble (XXXVI, ix.51-2), and for polishing, Egyptian sand from the Thebaid is recommended (XXXVI, ix.53).

We are once again treated to a list of sculptors in marble, of whom Praxiteles is still considered the foremost. Pliny delineates the original works of the sculptor in Rome at his time as being a Latona in the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine, an Aesculapius and a Diana in the Temple of Juno in the Porticae Octavia, and Asinius Pollio owns a Venus (XXXVI, iv.24). He also knows of and describes the famous Vatican Laocoön (XXXVI, iv.37), which after the fall of the city wouldn’t be rediscovered until 1506. He tells of several people who fell in love with statues, including all of those perverts making out with Praxiteles’ Aphrodite at Cnidus, and an eques, Junius Pisciculus, who once fell in love with one of the muse statues in the Temple of Prosperity, but Pliny doesn’t know which muse was the object of his affection (XXXVI, iv.39). He describes in one set of temples to Jupiter and Juno in the city, where the paintings that were to be in each temple were accidentally switched during installation, but afterwards, the mistake was left as is, presuming that the gods had condoned the error and this was how they wished for their sanctuaries to be decorated (XXXVI, 42-3).

Branching out from Rome, Pliny spends a fair amount of time discussing Egyptian matters, describing the mysterious, lost sound that the “speaking” colossus of Memnon made as a “creak”(XXXVI, xi.58), and (correctly) stating that the Egyptian word for obelisk is tekhen, and also knows that it is additionally the word for “sunbeam” (XXXVI, xiv.64). He holds with the tradition that Ramses II was the pharaoh during the Trojan War (XXXVI, xiv.65)—which is extra wild if you also hold that he was the Exodus pharaoh. Busy couple of years for world history… But mostly Pliny is here to be a pyramid hater: “They rank as a superfluous and foolish display of wealth on the part of the kings, since it is generally recorded that their motive for building them was to avoid providing funds for their successors or for rivals who wished to plot against them, or else to keep the common folk occupied.” (XXXVI, xvi.75). As a hater, he doesn’t have a horse in the pyramid construction debate, but puts forward the ramp (made of salt and soda) theory, along with the idea of bridges of (biodegradable) mud brick (XXXVI, xvii.81) Unlike Herodotus and Strabo, who hadn’t been able to see it, as it was still covered in sand, Pliny knows about the Sphinx and says that the locals claim that a “King Harmais” is buried inside, which may be a corruption of the name of the sun god Harmachis, aka, Horus (XXXVI, xvii.77). As an unrelated aside, he also claims that the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus was built on marshy ground in an attempt to protect the structure from earthquakes (XXXVI, xxi.95), which if true, was wildly unsuccessful, historically. But obviously Pliny thinks that the architecture of Rome far outweighs anything anyone else has ever done (XXXVI, xxiv). He says this despite the fact that Rome had a problem with lime theft, which led to buildings being erected without as stone mortar, which in turn led to frequent building collapses (XXXVI, lv.176).

After this, we have just general trivia about various rocks, including the so-called sarcophagus stone from Assos that could supposedly eat an entire corpse (sans teeth(?!?!)) in forty days, and could also turn grave goods to stone. Pliny also claims that the sarcophagus stone tastes salty (XXXVI, xxviii.132)—why would you try to taste it??? Obviously, all of this is unlikely: the translators think that this was probably fissile limestone in which lime was added to produce the corpse-eating effect (XXXVI, xxvii.131; n. e). A lot of this rocks section is devoted to space for the translators trying to identify what real stones Pliny could possibly be describing. Like eagle stones, which are supposedly gendered rocks that eagles need in their nest to produce young (XXXVI, xxxix.149-51). Back on his homeopathic bullshit, Pliny suggests geodes for eye-salves, and as a topical treatment for breasts and testicles (XXXVI, xxxii.140-1), as well as drinking lye as a cure-all. The translators suggest that he probably means an alkaline fluid strained through wood or charcoal ash (XXXVI, lxix.203; n. d)—please don’t drink lye.

Which brings us to Book XXXVII and gemstones, “Nature’s grandeur gathered together within the narrowest limits” (XXXVII, i.1), the very last book of the Naturalis Historia. Pliny seems to sort gems by color rather than stone composition (i.e., emeralds, green jasper, malachite, green porphyry, and greener turquoise are all basically considered one stone of varying quality). Though he does pick up on emeralds and beryl being the same correctly (XXXVII, xx.76). A lot of gems were thought the domain of not-Rome (India, Persia, Arabia, Egypt), and Pliny blames women for the rise in place of diamonds, emeralds, opals, rubies/garnets, and carnelian as the most prized Roman gemstones (XXXVII, xxiii.85) over more traditional stones like agates, which he says in his day are virtually worthless (XXXVII, liv.139). Roman women are also the only ones into amber (So far says Pliny ominously…) (XXXVII, xi.30-41), before going off on a long tangent about all the things that the Greeks get wrong about amber, “since it is important for mankind to know that not all that the Greeks have recounted deserves to be admired.” He also talks about an “aromatic stone” that he says comes from Arabia and Egypt, which might be ambergris, not a rock (XXXVII, liv.145).

He also describes individual pieces, such as an agate owned by King Pyrrhus that supposedly had Apollo and the Muses (with each of their attributes) on it that was found in that state naturally (XXXVII, ii.5-6), and the largest (150 lbs!) of rock crystal ever seen in Rome (XXXVII, x.27), dedicated to the city by Livia. For Pompey’s first triumph (over Mithridates), a portrait of him was made entirely out of pearls, and though Pliny admits that a man like him deserved such tribute, he acknowledges that such extravagance will eventually lead to Caligula’s pearl-studded slippers and Nero’s pearl-encrusted actor’s masks, symbols of extreme imperial decadence (XXXVII, vi.14-7). Augustus’ famous sphinx signet ring was supposedly one of two (hence why he could loan one out to his subordinates if necessary), which had been found among his mother’s effects at her death. People used to joke when a bearer arrived with one of the rings that “the Sphinx brings its riddles” (“aenigmata adferre eam sphingem”), which eventually made Augustus later change his signet to a portrait of Alexander (and defs not because Laksh and Aetia stole his sphinx…😉).

After one more alphabetical index of gems, Pliny ultimately opines that while India might be the land of gems, no other nation on earth is more diversely favored by the whole of Nature than his native Italy, proven by the breath of his praises for it that he’s been able to delineate throughout these thirty seven books. He gives second place to Spain, with Gaul and India (for its fabulous marvels) taking a third place tie (XXXVII, lxxvii.201-3). He ends with a call to his muse, Nature, and says to her, “Hail, Nature, mother of all creation, and mindful that I alone of the men of Rome have praised thee in all thy manifestations, be gracious unto me.” (“Salve, parens rerum omnium Natura, teque nobis Quiritium solis celebratam esse numeris omnibus tuis fave.”)

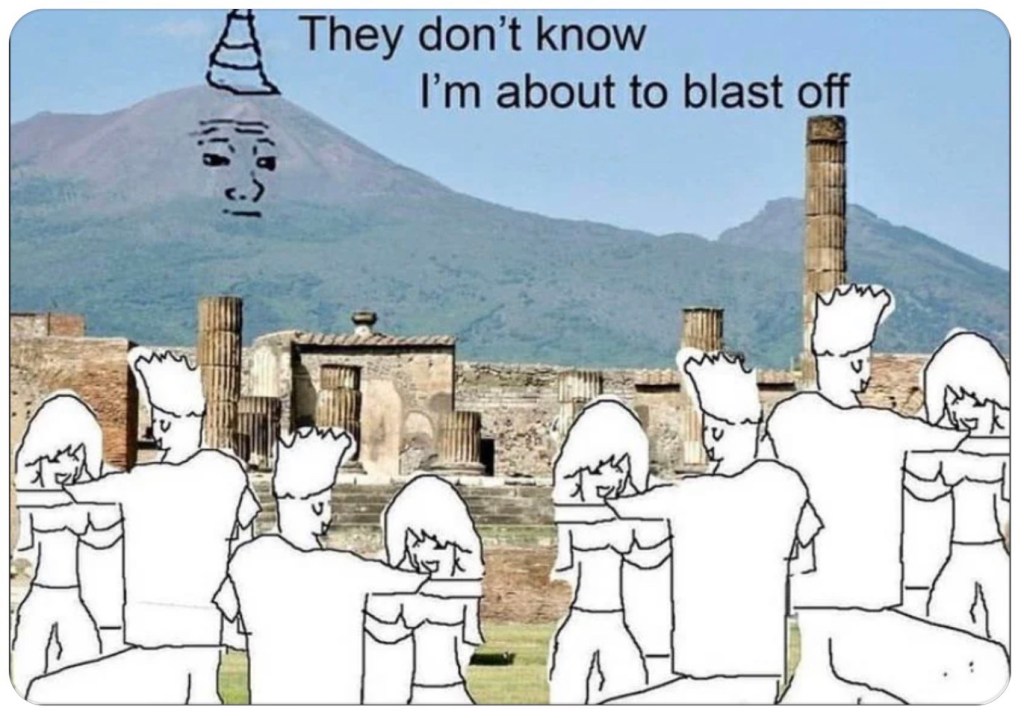

[Nature says: Get wrecked, Pliny 🌋🌋🌋]

Leave a comment