A few years ago here, we talked about the Japanese theatrical genre of noh (aka, the one with masks). While kabuki (the one with makeup) was and remains the more well-known and popular stage form in Japan, the older and more technical noh, born as it was from Shinto temple rituals, has deep roots, and is often considered the most quintessentially “Japanese” of the country’s art forms—whatever that might actually mean. But one of the most interesting things about noh is how precarious and almost serendipitous its very survival has been throughout its history, and I want to explore that a little bit today.

Noh’s first lucky break is the one we talked about in the earlier entry, where the military class shōgunates preserved noh after they took over the political power of the court-based aristocracy. Born as it was in Shinto ritual, which were deeply intertwined with the spiritual duties of the emperor, for its earliest history, noh had been almost exclusively an entertainment of the upper classes. But as is often the case across world history, the lower class generals who became the functional government of the new shōgunate were eager to adopt many of the trappings of the court culture they were ostensibly replacing to reenforce their legitimacy, and noh became a vehicle for this. The art form’s esoteric structure gave it a natural aesthetic sophistication, and its ties to the indigenous religious traditions (Shinto) provided the shōguns with two things they needed to consolidate their power off the battlefield: a government that “looked” like a government to the people it sought to rule (think of the use of conspicuous consumption in most world monarchies to enforce the social hierarchy), and the appearance of native religious consent to their rule.

Noh’s second lucky break was even more unlikely than its first, but—strangely enough—also came, arguably, from a military man. By the 19th century, noh was experiencing a general cultural decline, and after the end of the Tokugawa shōgunate in 1868, noh was no longer receiving government funding, as the imperial government of Emperor Meiji was more focused on modernizing Japan by adopting western industrialization and what was perceived as the more “modern” culture of Victorian Europe and the postwar United States. But according to an anecdote related by Donald Keene in his introduction to the Mishima plays we’re going to talk about in a bit, the Meiji government was influenced to change its mind about noh in part thanks to the encouragement, of all people, former US president Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885). Shortly after the end of his presidency, Grant embarked on a two-year world tour in 1877, partly as a gift to his long-suffering wife, Julia, and also in an unofficially official capacity as a free-roaming diplomat for the American government, as Grant’s military reputation abroad had survived his less-than-stellar presidential terms. Anyway, while visiting Japan near the end of the tour in 1879, Grant, who was more intellectual than he is usually given credit for, was taken to a noh performance, and supposedly at the end of the play, he was so moved by it that he told his escorts that they “must preserve” noh. (Five Modern Noh Plays, vii)

This endorsement from Grant, a figure who basically embodied all of the aims of the Meiji Restoration’s westernization goals, as well as the generally positive response noh received from other western foreign diplomats, convinced the Japanese imperial government to support the few companies still performing noh, as well as helping them expand their reach to the broader Japanese public. Though it wouldn’t be until 1957 that noh would be officially recognized as a mukei bunkazai, an Important Intangible Cultural Property (無形文化財), something that may have been helped along by noh’s third lucky break: the interest of writer Mishima Yukio (1925-1970).

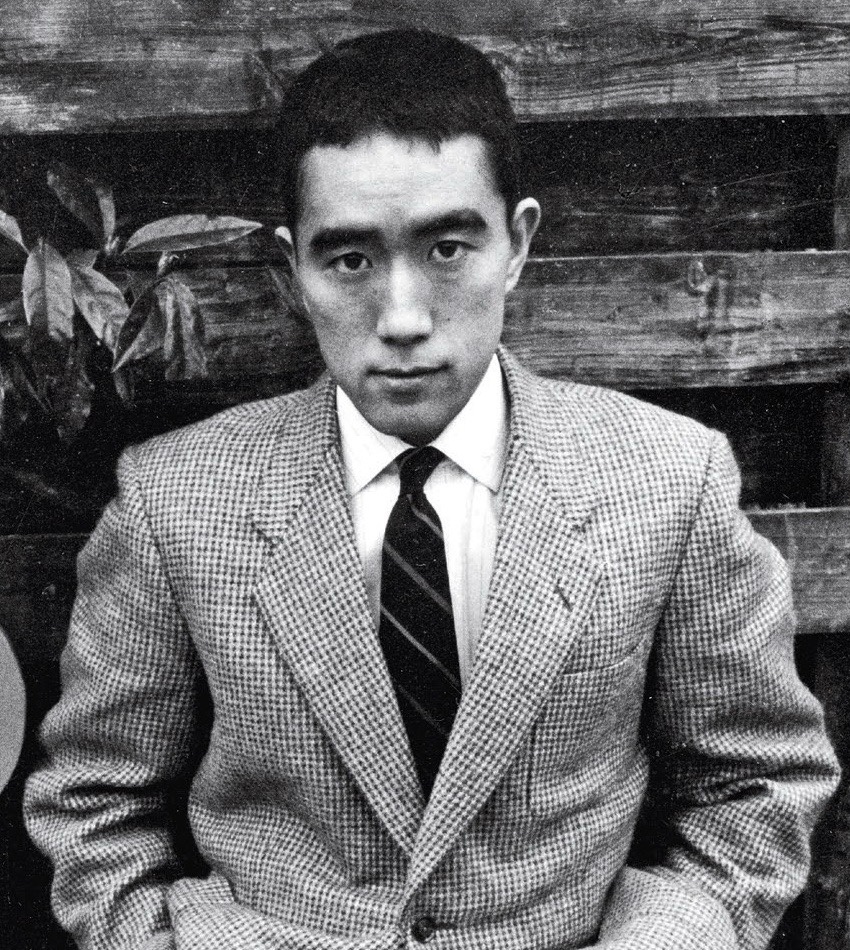

Mishima was the pen name of Hiraoka Kimitake, who like many of his literary predecessors, was born into a family of the remnants of Japan’s landowning, lower aristocracy and bureaucratic government class. Mishima’s father was a government minister, and his mother’s family was descendant from a ruling daimyō dynasty in Hitachi Province. According to Wikipedia, it was through his grandmothers that Mishima was introduced to classical Japanese culture, including noh.

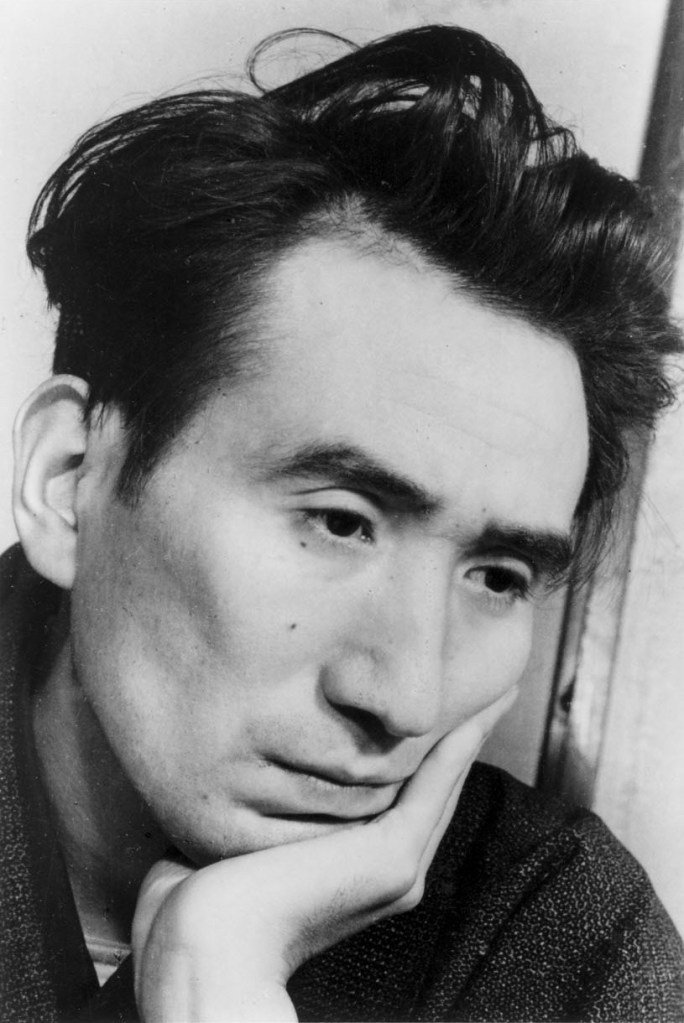

Modern Japanese literature in many ways initially followed the cultural swerve of the Meiji Restoration, as it was influenced by the 19th century more realistic, psychological novels coming out of Europe rather than the poetic medieval works that had been the norm. But the man usually considered the father of the modern Japanese novel, Natsume Sōseki (1867-1916), tried to thread the needle between “traditional” Japan and the westernized Meiji culture that he was born into—a balancing act that his literary descendants would have to grapple with as well. Early 20th century prewar Japanese literature is awash with great experimental stylists like Tanizaki Jun’ichirō (1886-1965) and Osamu Dazai (1909-1948) who pushed the boundaries of what a Japanese novel could include while still dialoguing with this east/west contradiction.

But much as the Meiji Restoration swung the pendulum between those two poles in one direction, the conservative hyper-nationalism of World War II produced an atmosphere that was more hostile to the perceived decadence of western influence on “pure” Japanese culture. This probably contributed to ne’er-do-well Dazai’s difficulty in breaking into the literary mainstream (though his alcoholism and drug habit didn’t help, either), and was part of the reason that the serialization of Tanizaki’s (most celebrated) novel, The Makioka Sisters, was censured by the military government and wouldn’t be fully published until 1948. Tanizaki would survive this repressive period and become one of the giants of the more liberal postwar literary scene alongside the much younger Mishima, but depression and substance abuse would lead to the in-between Dazai’s suicide shortly after the end of the war.

But despite being far younger than Tanizaki, Mishima was the far more conservative of the two, and I think their nearly forty-year age gap is the key to that. While Dazai was in his thirties during the war years and Tanizaki was in his fifties, Mishima was only twenty when the war ended, so his late childhood and adolescence was spent marinating in the regressive imperial culture that was being enforced at gunpoint at the time. Much of his oeuvre would be connected to a mythical, “purely Japanese” past and what would be viewed as traditional Japanese values, even as the wider country swung back toward the blended Japanese-American culture of the US occupation and beyond. That said, Mishima, especially in his early works, was capable of exploring sexuality as frankly as the more subversive Tanizaki, and his own (at least) bisexuality (denied by his wife, though supported by his semi-autobiographical novel, Confessions of a Mask) marks him out as an author who wasn’t always easy to categorize.

Mishima’s ambiguities would blunt somewhat with age as by the 1960s, he had become deeply aligned with the far right in Japan, in part because of his abhorrence for Chinese communism and the Japanese left which was at least sympathetic to it. Meanwhile, the left considered him a fascist because he’d pop off with statements like he didn’t “like” Hitler, though he thought that he was a “political genius.” He would however continue to disavow right wing violence against other Japanese writers and free speech—as I said, he was complicated. He became obsessed with a Cold War invasion from the Soviet Union and trained with the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (JGSDF), which is the closest thing to a standing army Japan was permitted to have under the Potsdam Declaration. Both of these things make more sense psychologically when you consider that he hadn’t been graded to serve in the imperial military during World War II, and had always felt inferior about it.

Unfortunately, all of this ultranationalism eventually led Mishima to attempt to stage a coup of the current Japanese government in 1970 by barricading the command offices of a military base in Tokyo along with a handful of loyal students who he’d been training as a private military force, with the intent of instigating an insurrection of the JGSDF to restore direct rule to the emperor. It did not work, and the JGSDF heckled Mishima as he read off his manifesto from the base’s roof. But, ever the traditionalist, Mishima had prepared for the eventuality that he would not succeed, and the students, as instructed, helped him commit seppuku, as any ancient Japanese rebel would have done. He was forty-five, and he left behind a controversial legacy in Japan where he is both a celebrated literary figure and an uneasy political entity.

Mishima’s five “modern” noh plays, despite their ultra-traditional subject—arguably the most Japanese of all Japanese theater—were written between 1950 and 1955, before his political leanings really started to go off the rails, so they’re not as preoccupied by a nostalgia for a lost Japanese past as some of his later novels and other works are. Indeed, their premise—updating five existing noh plays for a modern audience—is a very contemporary idea in the 1950s. To me, it was very reminiscent of the intent behind Jean Anouilh’s modern adaptation of Antigone, which was actually the first version of Sophocles’ play that I ever read, in part because with its stylization and use of masks, there is something vaguely Greek in noh. Mishima’s genius in his adaptation is to contemporise the settings of these plays without entirely sacrificing the structure or poetry of the original plays. There is more dialogue in Mishima’s versions, but you get the same sense of talking past one another that noh tends to give off, the same eerie sense of being taken out of the ordinary in order to touch the uncanny.

The five plays Mishima is adapting are Sotoba Komachi (Komachi at the Stupa), Aya no Tsuzumi (The Damask Drum), Kantan (The Magic Pillow), Hanjo (The Waiting Lady With the Fan), and The Lady Aoi (Aoi no Ue). Of the five, only The Damask Drum was conceived by Mishima with truly traditional noh staging in mind, with the others straddling the line between noh and more western theatrical staging, and The Lady Aoi even being fully staged as as sung western opera in 1956 (Five Modern Noh Plays, xii). Seeing how this was Mishima in his less nationalistic phase, he even suggested that if, say, a production of Sotoba Komachi were stage in New York City, its park setting could and should be changed to Central Park and the dream sequence to take place at a similarly opulent dinner setting in the city like Delmonico’s instead of the thoroughly Japanese Rokumei Hall (ibid). Because, as we said in the previous entry, noh is about mood, rather than the specificities of setting or character.

To look at one of the plays, Sotoba Komachi is one of several classic noh plays that on their surface seem to be about a specific character, namely the Heian era poet Ono no Komachi (c. 825-900), but they’re not really about the historical Komachi. Rather, they are about Komachi as an idea. Komachi was considered one of the most beautiful women of her time, famous for sensual poetry and her (supposedly) many lovers. But even beautiful women age and die, and obviously Ono no Komachi was no exception, and her long afterlife as a subject of noh positions her most strongly as an ideogram for the folly and transience of life. In the classic Sotoba Komachi, she is a hideous old woman haunting a Buddhist stupa and is in turn being haunted by the ghost of one of her lovers whom she treated cruelly. As with most noh plays, the only release from this decay and transience is spiritual release through Buddhist enlightenment.

In Mishima’s version, most of the Buddhist elements are excised (probably because Mishima was more devoted to native Shinto personally), and rather than annoying priests at a Buddhist holy site, Komachi is depicted as butting in on lovers making out in one of Tokyo’s parks; her mere presence as a decrepit beggar throwing off the mood. The priests are also replaced by a young poet who mocks Komachi’s claims to having once been a great beauty until—instead of Komachi herself—he is possessed by the spirit of her dead lover in an extended dream sequence where Komachi is transformed in his eyes into her former glory, though the audience only ever sees the old Komachi. She warns him that if he doesn’t stop that he’ll die like the lover did, but he is unable to listen to her warning, and when the scene returns to the park, the poet is dead. A policeman asks Komachi what happened to him, but only laughs when this old woman says he died because of her beauty. Mishima strips out Komachi’s original resolve to pursue enlightenment and simply has her return to what she’d been doing at the start of the play: gathering old cigarette butts to smoke.

Transience, illusion, and unrequited love are the hallmarks of all the plays Mishima chose to adapt from the classic catalog. The adaptation often comes from placing contemporary people in the situations of the old play, and the result reflects the ambivalence and ennui of postwar life in Japan. In the original Kantan, the protagonist needs to dream about being the emperor of China to learn that all of the riches and pleasures world are illusions, but Mishima’s cynical young protagonist is already bored of life and knows that nothing really matters. The illusions even have to break off their puppet show to scold him for ruining the whole dream by not playing along as generations before him have. In the original Damask Drum, the protagonist at least gets to haunt the princess he fell in love with to punish her for not returning his affection, but here in adaptation, his ghost still cannot make himself heard to the fashionable young woman he loved from afar. Even in a play like Hanjo, where in the original, the heroine’s madness is lifted by her lover’s return, Mishima changes the ending so that she cannot recognize him anymore and they remain parted. In Mishima’s noh, the world is not only an illusion, but a tragedy.

To wrap up, I want to briefly touch on the fifth play, The Lady Aoi, because I think it does a good job of encapsulating everything we’ve talked about. It is perhaps the most Japanese of all the plays because even the original is an adaptation, taking an episode from the Japanese novel, Murasaki Shikibu’s Tale of Genji, where—after a frankly stupid but very Heian spat about prestige at a public event between Genji’s former lover, the so-called Rokujo Lady, and Genji’s wife, Aoi—Rokujo’s vengeful spirit, unbeknownst to her, attacks Aoi through spirit possession, which eventually kills her. The episode so horrifies Rokujo that she decides to leave the capital and accompany her daughter, who has been named priestess at Ise Temple, into a spiritual retirement to atone for what her unchecked spirit did.

The shite, the “doer” of the classic noh play, is Rokujo (as you can see in the picture at the start of this entry, because her madness is possessing Aoi, her actor wears a demon mask to illustrate this). Her tsure, or companion, is the miko, or female shaman, who is attempting to channel away Rokujo’s angry spirit from Aoi by acting as a medium between them. The waki, or audience surrogate who drives the action by asking questions of the shite is, as is so often the case in noh, a priest, who here is the exorcist brought to treat Aoi alongside the miko. There is also a wakitsure, or waki companion, who is an official from court. What might surprise you is that Aoi herself is nowhere to be found in the play that bears her name, only being represented by a rare noh stage prop, namely, an empty kimono. That’s because despite the title, it is Rokujo’s rage, her lost love with Genji, her aging beauty, and her jealousy that threatens her spiritual life that are the real focus of the play. How Rokujo’s destabilizing emotions must be addressed and dispelled not only if Aoi is to live, but if Rokujo can be saved.

Mishima’s first move in adapting this play is to place it in a more recognizable context for his contemporary audience. He pulls out all of the metaphysics of Heian belief in spirit possession and addresses it as a modern person would: Aoi is experiencing some sort of psychological trauma and is being cared for in a mental hospital. The priest and miko are gone, and replaced with a nurse and Genji himself, who is also conspicuously absent from the original play. Aoi is more than an empty kimono here, but in the spirit (heh) of the original, she is a nonspeaking part in her hospital bed, aside from some moaning. Rokujo arrives in concert with an eerie ringing of the room telephone, and at the end of the play, the “real”(?) Rokujo is only heard through the phone. But the other Rokujo speaks almost simultaneously out of sight on the other side of the door, begging the question of which is real, and what or Genji and Aoi actually experiencing. By placing Genji at the center of the action alongside Rokujo, Mishima is asking whether it is Rokujo’s spirit (memory) that is harming Aoi, or is it Genji’s memories of her that are killing his wife? A medieval ghost story becomes a modern psychological drama through these small tweaks. But the real question I found myself asking at the end of these adaptations was whether approaching these plays from a psychological perspective is really any different than the interiority of traditional noh’s probing for what lies beneath the plain surface. Confronting and understanding emotion are universal experiences, and both types of noh achieve it in equal, albeit distinct, measures. If only Mishima had remembered in his own life that tradition can adapt, too.

Leave a comment