“Once upon a time, there were larger, more elegant cities here, though now it was just one of many out-of-the-way places that dipped their feet in the river’s edge. Tombs from before even the Egyptians’ long memories begin dotted the surrounding desert, ones of massive scale said to be made when the gods were young and humble burrows in the sand where the old ones buried their dead before Anubis came and taught them mummification.” – The God’s Wife, chapter 49

I realized in the five years since I’ve been posting here with any regularity, and the six years since The God’s Wife came out, I haven’t tried to deep dive with all of you about the most important setting in the series outside of Alexandria and Rome: the city of Ombos. Some of that is because, in spite of its long history, there is a dearth of archaeological evidence for vast swaths of existence—which makes it enticing as a secret base for your cast of historical rebels and exiles, but makes it somewhat difficult to talk about in the more factual realm. But the breadcrumbs we do have are interesting, so I thought this week we’d take a look at what we do know about one of the oldest cities in a very old civilization.

Firstly, let’s talk about the names of this city, which, by the dint of its millennia-spanning existence, it has many. Ombos is actually one of the latest of its names, being its Greek name assigned by the Ptolemies in the 4th century BCE, and it is a mark of the city’s insignificance during this period that it is hardly differentiated in the Greeks’ records from the relatively nearby (and much more important at this point) Kom Ombo.

This confusion comes from the fact that both of these cities (at different points in Egypt’s long history) have answered to the name Nbwt/Nbyt (w/y are mostly interchangeable in transliteration of Egyptian hieroglyphs), or Nebut/Nebyt in translation, which means City of Gold, or Gold City. This recognized Ombos, and later, Kom Ombo, as located in some of the earliest mining hills worked by the ancient Egyptians. Much of settled ancient Upper (southern) Egypt isn’t “classic” desert, that is, big Saharan sand dunes and oases, but rather cavernous, rocky hills and dry wadis carved by abandoned tributaries of the prehistoric Nile. These hills, made by the movement of one of the world’s great rivers, were rich with mineral deposits, and at least in their earliest history, the gold for which one of its first cities would be named.

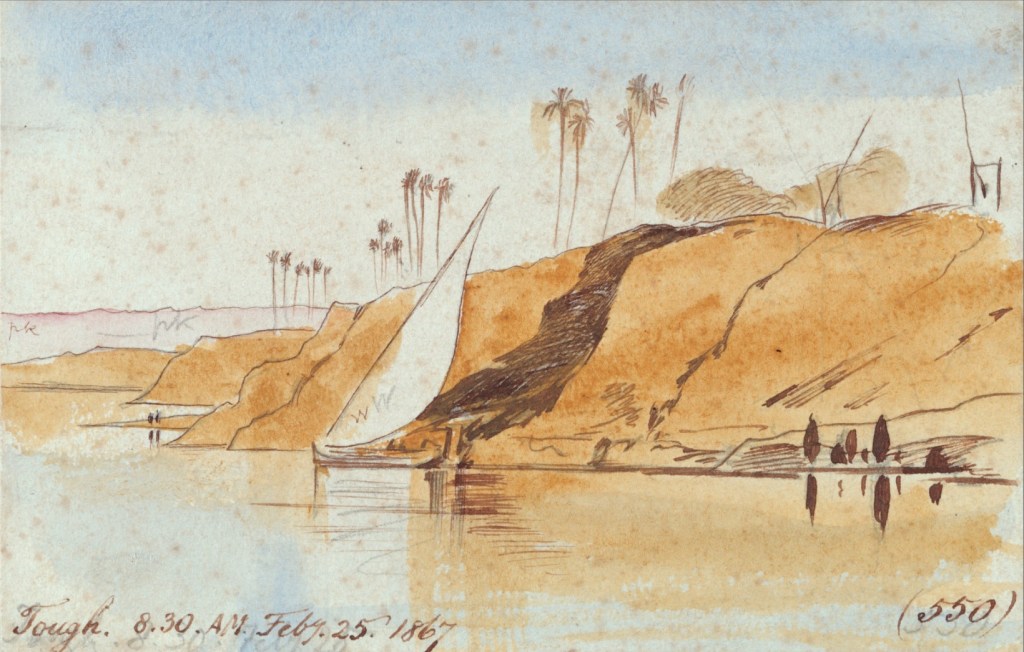

[This wadi is in Jordan, but it gives you a feel for the type of topography that I’m trying to describe.]

Ombos would also be known as the City of Gold because it was one of the earliest seats of proto-dynastic organized government in Egypt, and therefore, what riches didn’t come from its own backyard were likely diverted from its dependent communities. And that is why some of Ombos’ history is obscure to us, because its era of greatest consequence was at the very dawn of what we can even call ancient Egypt. The two millennia spanning 4000 BCE to the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt that ushered in the beginning of dynastic ancient Egypt around 3150 BCE—nearly four thousand years before Alexander and the Ptolemies showed up—is, ironically, named for the very last of Ombos’ many appellations, the one it had been wearing since the Islamic Conquest of Egypt in the 7th century CE: the Naqada (نقادة) Period.

[Occassionally, to add yet another name, archeologists choose to spell it “Nagada” instead of Naqada, a hazard of translating between the Roman and Arabic alphabets.]

The Naqada culture is the name given to this transitional era in Egyptian history, where Egypt moved from a Paleolithic society of family groups to a one of Neolithic tribal chieftainates, and to the cusp of centralized monarchical governance. Since Ombos’ first excavations by English archaeologist Sir William Flinders Petrie (1853-1942 CE) in the 1890s, this extensive period has been generally divided into three sub-periods: Naqada I (~3900-3650 BCE), Naqada II (~3650-3300 BCE), and Naqada III (~3300-2900 BCE), after the earliest dynastic rule of Egypt settles into the Old Kingdom period.

[Like many white men of his time, Sir William Petrie was a eugenicist and at first believed that his discoveries in Ombos showed evidence of a heretofore unknown, presumably white/Semitic, race that had founded ancient Egypt as we understand it—one that would be divorced from the Coptic/Arab African Egyptians that populated the modern country for whom Europeans had nothing but disdain. This turned out to be so unprovable even in the racist milieu of 19th century Anglo-French Egyptian archeology that he backpedaled on the theory pretty quickly. Also, in true eugenicist form, he donated his preserved head and brain to the Royal College of Surgeons in London after his death, though the story about his widow transporting it from Jerusalem to England in a hat box appears to be, unfortunately, apocryphal…]

Most of our knowledge of any of the Naqada periods comes from the vast necropolises that fill the hill country around the vague demarcations of where we think the living city was located. For most of Egyptian history, including much of the modern era, buildings made of stone were almost exclusively for the gods (temples) and the dead (tombs); that’s why those are what you see if you go on the tourist routes. The living, even the pharaohs, lived in buildings largely made of mud bricks taken from the Nile’s silt, and as such, most of an ancient Egyptian city or village wasn’t built to last down through the centuries, and it’s only because of Egypt’s uniquely suited dry climate that preserves more fragile artifacts than most that we have as much idea of basic living architecture as we do.

The dividing lines between the three Naqada periods are drawn mostly according to evidence accumulated from the grave goods in the various necropolises, which show the changing complexion of life in Ombos during the time before a unified Egypt. The earliest Naqadans, those from the first period and the earlier parts of the second, weren’t mummified in the traditional Egyptian sense of the word. These are the Egyptians who have been discovered naturally preserved by the natron and salt of the desert ground, tucked into a crouching, fetal position rather than stretched out on their backs. However, this is not to suggest that the first period Naqadans were lacking in sophistication. These earliest Egyptians, as evidenced by the things they were buried with, were already trading with their foreign neighbors in Nubia for materials like flint-grade obsidian, and charcoal samples show that they were even in contact with the Levant, as the wood is identifiable as coming from the famous cedars of Lebanon. And their native pottery was already at this early date both hand-shaped and wheel-spun, usually with a distinctive red and black pattern that suggests it required a more complex double-firing to achieve.

[I say “suggests” because even modern archeologists and art historians in the 21st century, like with the famous Egyptian blue dye, have had difficulty consistently replicating how these pots were made.]

The second Naqada period is where more complexities emerge in the necropolises. There are more indications of burial rituals with the tombs; some bodies are still buried nakedly in their graves, but more show evidence of the first rudimentary mummification (i.e., linen wraps) and things like bodies being positioned facing east (to greet the sunrise). This is also when more evidence of primordial deities like the proto-Hathor celestial cow goddess Bat appear in figures and on the increasingly diversely patterned pottery. Bat’s arrival might also indicate a greater shift in Naqadan culture toward pastoral agriculture aided by the earlier Naqadans being first adopters of Egyptian irrigation technology.

[Naqada II pot showing a figure sailing in a (ceremonial? necromonial?) boat accompanied by a female deity (likely Bat). The two rows of symbols floating above them to the right may symbolize her horns and her connection to the sky.]

By the third period, the Naqadans are being buried with identifiably “Egyptian” items that match a rapidly consolidating culture ultimately driven by the unification of Egypt by the slightly mythological predynastic king, Narmer (c. 3100 BCE). Their pottery experiments are more preoccupied with different shapes, as opposed to decorations, and—perhaps most excitingly—the very first written scripts and proto-hieroglyphs appear in Naqada. But this will ultimately be the high-water mark for the Naqadans as we understand them, and Ombos will largely fade into the background of Egyptian history until the 15th century BCE, nearly two thousand years later.

[Here on the famous Narmer Palette, although found in Nekhen, you can see all the hallmarks and achievements of the Naqada III culture: a distinctly “Egyptian” art style, and proto-hieroglyphs in the form of the king’s serekh—his name enclosed in divine protection—that you can see at the top center of both sides of the palette. But also notice that his serekh sits between two depictions of Bat, still held as the celestial mother goddess who spatially outranks the newly-appearing falcon deity below her.]

We’ve mentioned Bat a lot so far, but those of you who know (either from history or my books) that Ombos was considered the main cult center of Set may find it strange that he hasn’t come up yet. Part of that is that so much of Set’s origins are shrouded in mystery. He was a very old god, but the how and when of his actual first appearance in the Egyptian pantheon is up for debate. There is a tomb in Ombos dating from Naqada I that has the depiction of an animal that might be the sha, the Set-Beast, but as we talked about in my latest round of lesser-known Egyptian gods, this could very well be the predynastic god Ash, who both looks like Set and was originally denoted as Nebuty—He of Nebut. But just as Bat would eventually be absorbed by Hathor, it is possible that Ash is merely a proto-Set in the same way. The macehead of early dynastic king Scorpion II (c. 3200-3000 BCE) also appears to have a pharaonic standard that depicts an animal that looks like the Set-Beast, but there’s no way to be certain. Both of these at least point to an established early cult to the god, or a similar deity, in Ombos.

[Part of the Scorpion Macehead, with an animal standard that, again, bears a resemblance to the sha (circled in red).]

More concrete (sort of literally) evidence of Set’s presence in Ombos comes from the remains of his temple, the earliest parts of which date from the reign of New Kingdom pharaoh Thutmose I (1503-1493 BCE). Petrie found some evidence that a temple existed on this site as early as the Fourth Dynasty (~2613-2498 BCE), and had been added to during the Twelfth Dynasty (~1991-1802 BCE), but those structures had been primarily in mud brick and Thutmose renovated the structure in limestone. Both he and his grandson, Thutmose III (1479-1425 BCE) would sponsor work on the temple, and frankly, if Thutmose III’s name is on the work, there’s a good chance that his aunt-stepmother co-ruler Hatshepsut (1479-1458) probably had a hand in Ombos, too.

Unsurprisingly, the Ramsiads of the 19th Dynasty that followed them, with their deep familial roots in Southern Egypt and the Set priesthood in particular, also appear to have sponsored augmentations to the temple, with archaeological fragments and documentation dating from the reigns of both Ramses II (1279-1213 BCE) and Ramses III (1213-1203). Like with the situation between Thutmose III and Hatshepsut, Ramses both spent several years as co-ruler to his father, Seti I (~1290-1279) and completed many of their joint building projects during his own solo reign without specifically mentioning his father (Ozymandias needs his credit, after all). So it is possible that Seti, the pharaoh whose name literally means “Man of Set,” would have been particularly interested in maintaining his patron god’s most prominent temple, especially given the otherwise atrophied state of Set’s cult in wider New Kingdom Egypt.

[Despite his name and personal inclinations, Seti was always careful to balance his affiliation with Set against proper respect to the dominant cult of the period, the so-called Abydos Triad of Osiris, Isis, and Horus—which, for obvious reasons, had little love for Osiris’ supposed murderer. He and Ramses II were major builders and patrons of the great temple at Abydos, Osiris’ main cult center, and anywhere Seti mentions himself within the temple grounds, he generally uses his ruling praenomen, Menmaatre (“Eternal is the Justice of Re”), rather than Seti, out of respect for Osiris and his death.]

After the New Kingdom, Ombos seems to have retreated into the shadows again and largely became the diminished village that the Ptolemies would find it. Burials from the Late Period (~664-332 BCE) before them would be found by archeologists, but with nothing of the pomp of any of its heydays, either as a government hub or as a city with at least the reputation of having a small elite population. Set’s continued slide into cultural demonization certainly couldn’t have helped matters, nor did the shift of power to Alexandria far away in the north.

Eventually, Coptic Christians would settle in the area for safety in the 4th century CE, far from the control of first Rome, then later the Fatimid caliphate and the Ottomans, but their numbers would always be small. Yet their Greek name for Ombos, Nekatērion (ⲛⲉⲕⲁⲧⲏⲣⲓⲟⲛ), would be the one from which the modern Arabic town of Naqada derives. A census in the 1960s would show that the population of Naqada had dipped to barely 3,000 people, mostly Copts, but today that number is close to 189,000 (as of 2021). This is still an extremely far-flung, rural part of Egypt, far from Cairo and Alexandria, so there is little expectation of that number ever climbing much higher than that, though. And in this, modern Naqada isn’t terribly dissimilar from the town I imagined my God’s Wife heroines living in during the 1st century BCE/CE. An out-of-the-way place easy to miss as the river bends to east between Abydos and Thebes—but also a place with plenty of secrets if one is willing to dig a little deeper.

[The perfect place to hide my special girls👑]

Leave a comment