I haven’t done a museum entry in a while, and the Carnegie Museum of Art has some new exhibitions that caught my attention last week, so I thought we’d take a look at some of what’s on offer for the spring quarter.

[My nebbiness in the Hall of Architecture, of course, remains incorrigible. This stuff is definitely exhibition-related, but I’m not sure what. Possibly pieces for this year’s local Youth Exhibition. Exciting!]

CMOA’s Forum Gallery is a single-room exhibition space that rotates on a roughly quarterly basis dedicated to living artists in the contemporary art scene, and the current series is by Colombian artist Gala Porras-Kim (b. 1984), whose photographic work and intricate colored pencil pieces for this exhibition explores how museums and similar institutions catalog and curate their collections, and how that influences how we perceive “art.” As she elaborates (and we’ve discussed several times on this blog), “[a]rt is not a fixed category, and question[ing] the conceptual frameworks and individual subjectivities that go into presenting and understanding an object as a work of art” is an important aspect of both engaging with the past and helping museums move forward into a more equitable future.

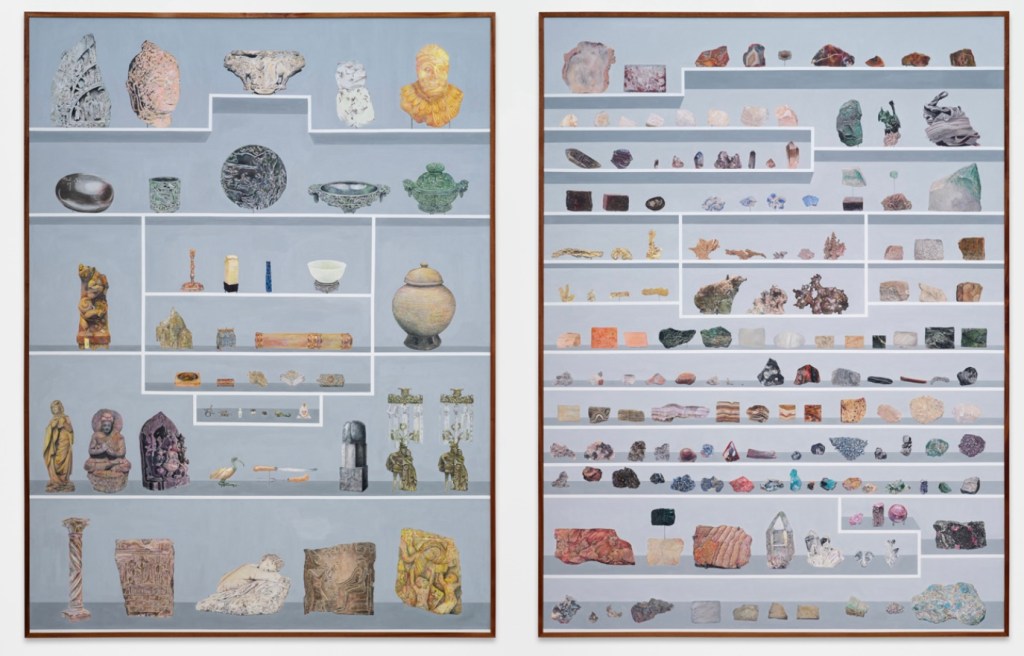

Kim’s pieces are divided into two categories, the first being large-scale colored pencil drawings of objects she found in CMOA/CMNH’s collection archives categorized by their materials (glass, minerals, etc) and shows how categorization can both influence and change how an object is presented and perceived. For example, in the paired pieces below, classifying both carved objects and mineral samples as simply “mineral objects” may change how both are viewed by an audience.

[202 mineral objects at Carnegie Museum of Art or at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, 2025]

[202 mineral objects at Carnegie Museum of Art or at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, detail]

For example, this stone Ganesh used to be on display in a CMOA wing (gosh, I miss this ancient art wing—I wish they’d bring it back…). Displaying it based on its composition, rather than its historical or religious significance potentially changes its meaning, and in the case of the paired Carnegie museums, potentially changes whether this object is more suited to an art museum or a natural history one. We don’t always think about how museums as institutions mold how we as the public understand art, or engage with broader socio-cultural issues like collection providence and ethics, but as we’ve said before, the best modern museums are both grappling with these issues and inviting the public to explore them, too.

[Ganesh, detail (photo from April 2018)]

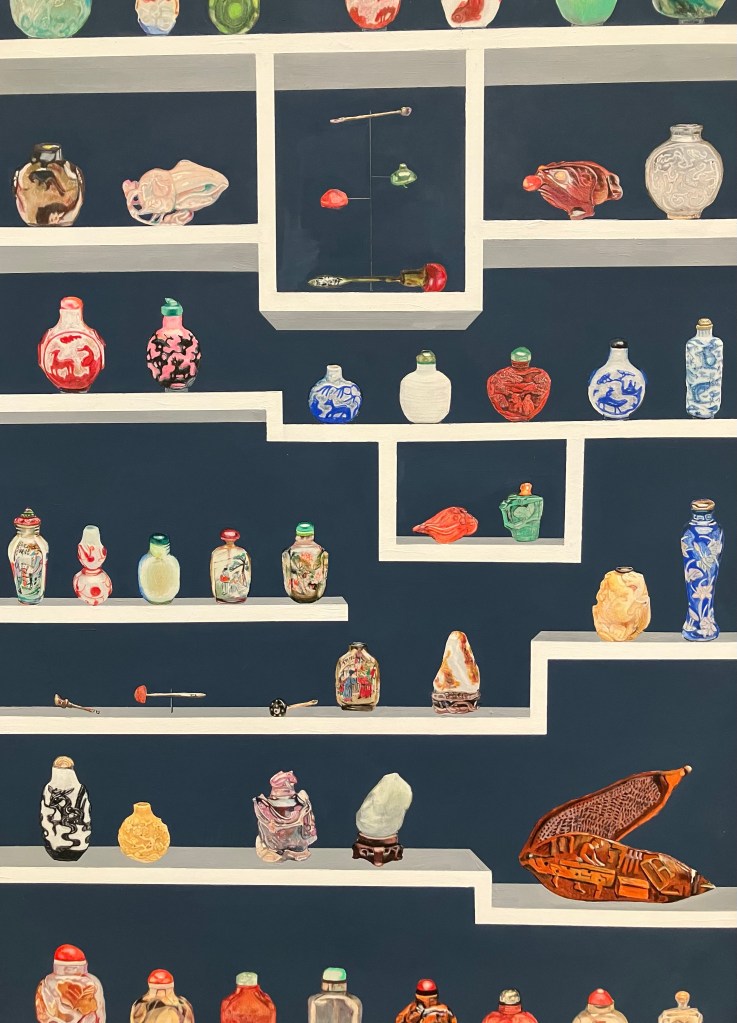

[75 snuff containers at Carnegie Museum of Art or at Carnegie Museum of Natural History, 2025. For the record, I would also love to see a whole wing/exhibition of CMOA/CMNH’s snuff bottle collection; though maybe not having one is for the best for me. I went through a period about ten years ago where I got waaay too into looking for vintage Asian snuff bottles on eBay… What can I say? I have a weakness unique, small-piece art😬]

[Just a few of the bottles I ended up with in those fugue years]

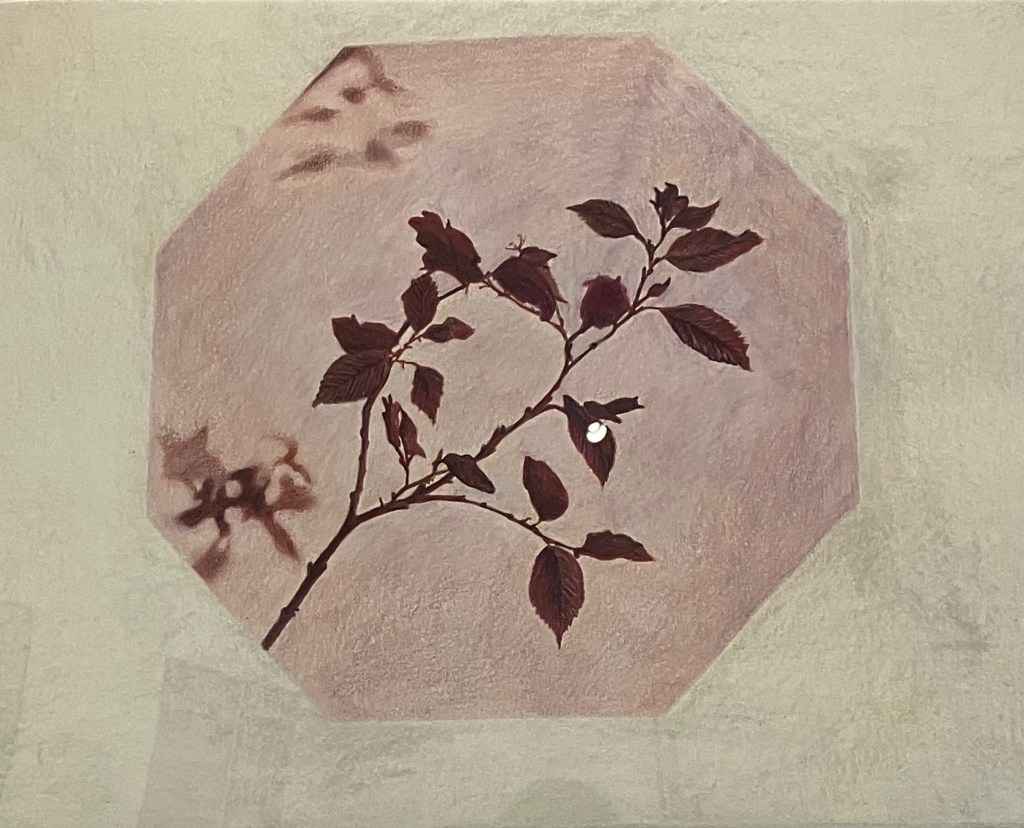

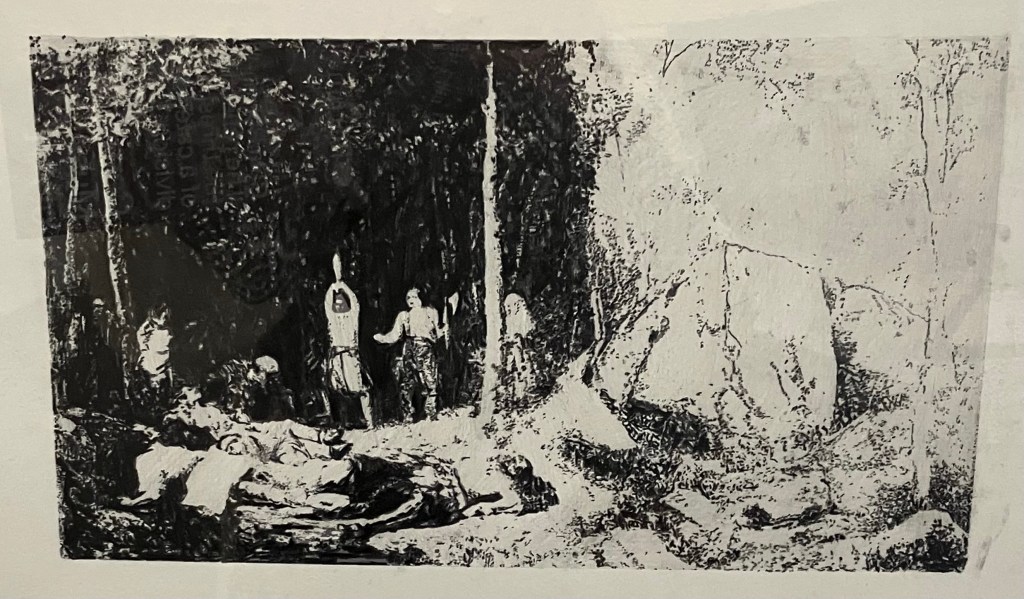

Smaller, but no less interesting are a series of photographs Porras-Kim took of archive pieces/instillation proposals that aren’t publicly accessible, and the various reasons institutions make the decision to not display a work of art. Some of them involve ethical issues we’ve talked about previously, such as a piece is culturally insensitive or has components that are problematic (like human remains) either in content or providence (we don’t know if those remains were obtained legally, etc). But aside from issues like this, that some people may still believe are solely rooted in ultra-woke leftist ideologies, Porras-Kim highlights other institutional concerns such as works that are too sensitive to light or air to be displayed; works that lack context for an audience, or have not found an exhibition yet that would give them that context; or, my personal favorites, works that are too big/impractical/dangerous to be displayed around the public, or works the artist just has unrealistic expectations about. It’s a really interactive way to discuss how museums go about the business of curating their collections and bringing the public into that process. Anyway, the Forum Gallery is so small that I don’t usually get to have this much engagement with the current exhibition, but I really liked this one both aesthetically and because it tied in so well with things we’ve talked about before.

[Silver salt film photograph depicting a plant and its extending branches. Least likely to be on view because the silver salts are unfixed and if the work is exposed to light, the photograph would continue to darken until the image disappears.]

[ Canvas painting, 361/4 x 42 1/2 in. (92.1 x 108 cm). The painting shows a clearing in the woods with heavily-leaved trees and large, vertically standing boulders; a small opening of leaves reveal a patch of pink and gray sky above a distant mountain. In the landscape, eight figures stand on brown dirt ground; five are Abenaki men, three are white female colonists, and four of the men are lying on the ground. Least likely to be on view because of the violence depicted against a population that is part of a confederacy local to the museum.]

[An art installation that involves large amounts of crude oil to be pumped through it. Least likely to be on view because it is too expensive and technically challenging to install. But imagine how cool this would be!]

[Wedding cake topper from the early 20th century; bride died the night before the wedding. Least likely to be on view because there is no immediate context to show it in.]

[And my absolute favorite: A delicate wall-hanging made of thousands of very small sharp objects. The artist insists the work cannot be shown with any barriers, floor tape, or glass in front, or guards nearby. Least likely to be on view because the museum is not capable of showing the work according to the artist’s wishes without risking possible injury to visitors and damage to the work.]

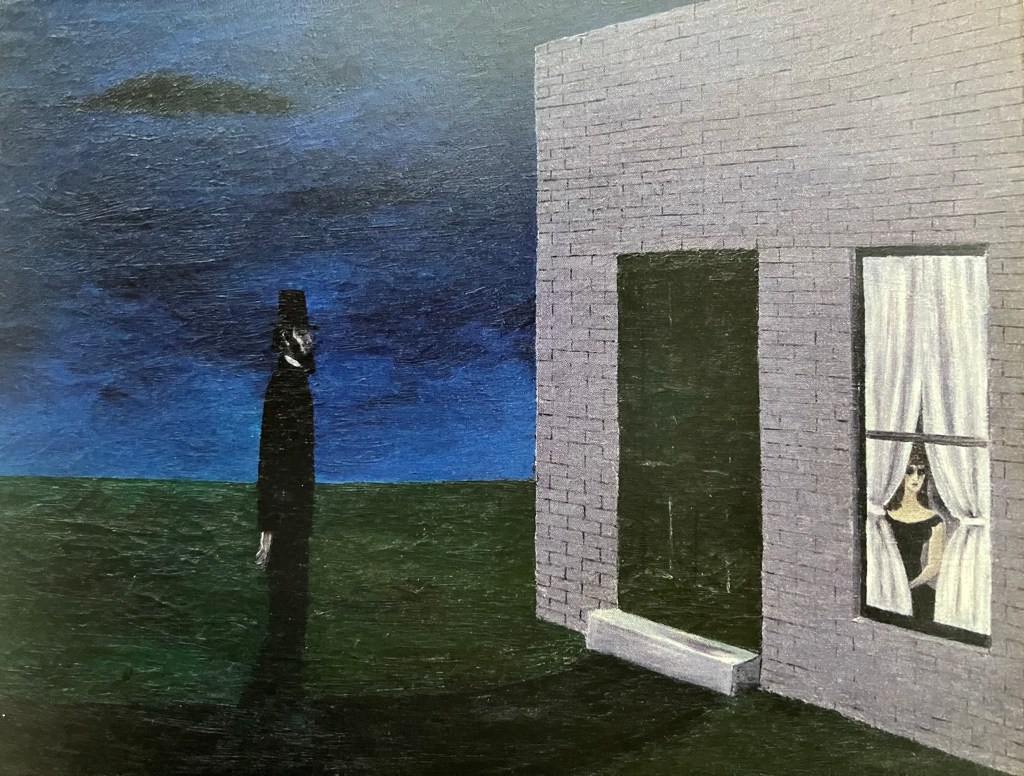

The Forum exhibition was a bit of a surprise along the way, but the main reason I’d hopped down to CMOA was to see the retrospective exhibition they were putting on upstairs in the Scaife Gallery for the midcentury surrealist Gertrude Abercrombie (1909-77), who I honestly didn’t know much about going in, but whom I’m obsessed with now. A central figure in the Chicago art movements of the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, Abercrombie was influenced by other artists like René Magritte and Edward Hopper, but also by her deep personal connections to the Chicago jazz scene, especially leading figures of bebop style like Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, many of whom would hold practice sessions and late night jams in her Hyde Park apartment. Gillespie himself would call Abercrombie’s artistic style bebop in visual form: “Gertrude Abercrombie is the bop artist, bop in the sense that she has taken the essence of our music and transported it into another art form.”

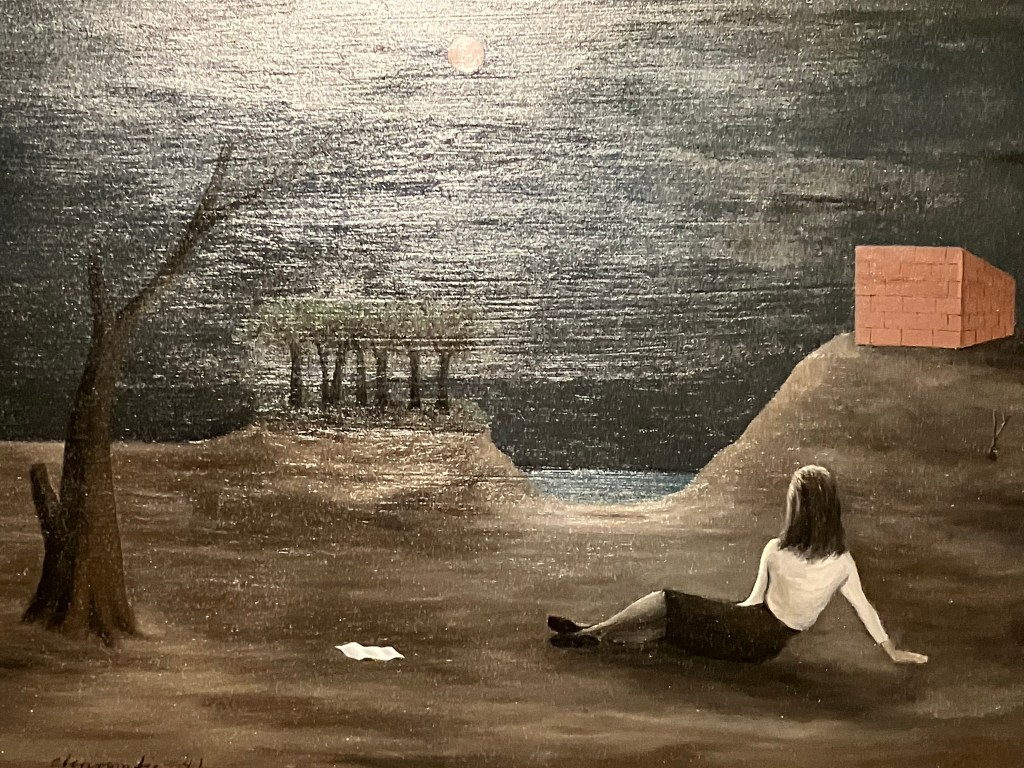

[I actually gasped when I first saw this one, Reverie (1947), because I was like, “Oh! This is Abercrombie’s take on Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World!” Imagine my surprise to discover that Christina’s World wasn’t painted until 1948. I can’t find any suggestion that Wyeth and Abercrombie were aware of each other, so the similarities might simply stem from their shared background in the contemporary American realism movement. But I find it very interesting.]

[Christina’s World, Andrew Wyeth (1948)]

[Charlie Parker’s Favorite Painting (1946). Like much of jazz itself, Abercrombie was not typically a specifically political artist. But just as jazz’s status as the art of a marginalized group sometimes made itself inherently political, she was not against political art. Possibly inspired by friend Billie Holiday’s classic song, “Strange Fruit,” and definitely as a response to the racial violence experienced by returning Black GIs after World War II, this painting places a lynching noose in one of Abercrombie’s usual surrealist landscapes, which both highlights the un-reality of a world that allows these murders to happen as well as her conceit that her paintings are the real world, no matter how strange they may first appear.]

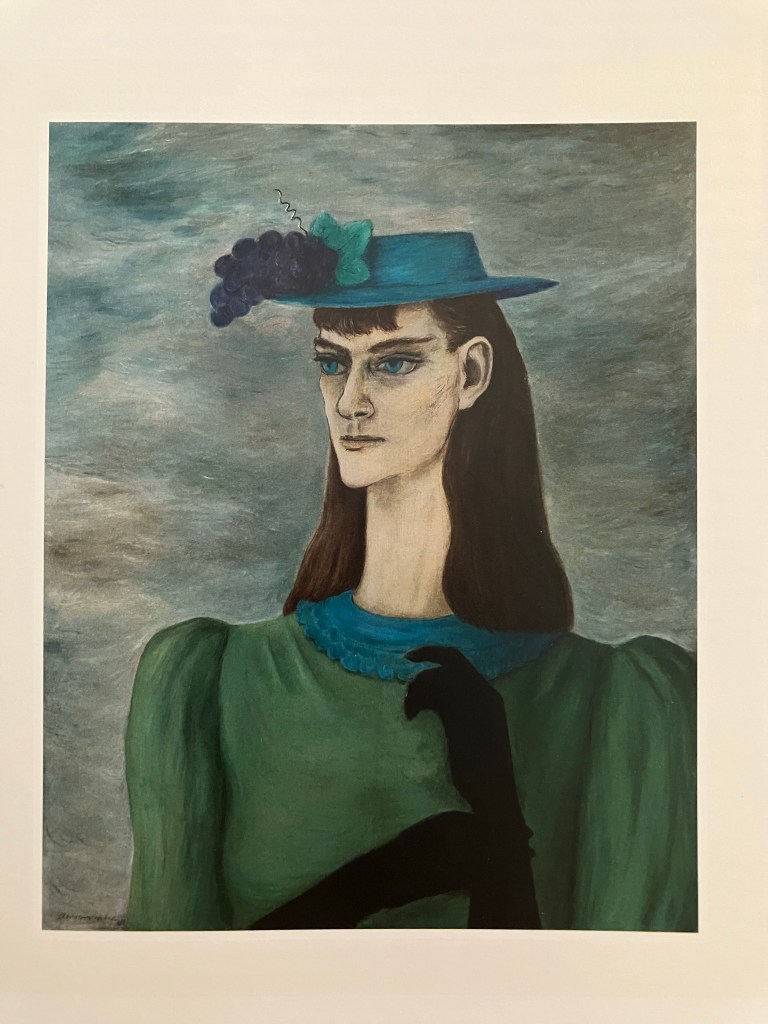

For her part, Abercrombie, adverse to labels, didn’t see her work as bop or surrealist per se, but simply as an extension of herself and the world around her. Declaring in a quote used as the title of this exhibition, “the whole world is a mystery,” and her art was merely depicting “simple things that are a little strange.” Unabashedly autobiographical in much of her work, she saw painting herself and her surroundings as the only way to access “real” art and emotion. If her paintings are surreal or liminal in nature, it is because the world is often a surreal and liminal space. A place where common objects become totems in our lives through our experiences, where our dreams cannot always be neatly compartmentalized away from the waking world. Abercrombie’s closest friends were generally from marginalized communities, Black and queer artists living in midwestern America during very outwardly conservative times—if her paintings are a little “odd” or “surreal,” it is because she was most comfortable in this borderland space rather than the one experienced by “normal” Chicago.

[The women in her paintings are always Abercrombie herself, even when the painting has a title like this one of Self-Portrait of My Sister (1941)(Abercrombie didn’t have a sister). Her different roles within her paintings—woman, bride, sister, magician, queen—are merely aspects of the artist, masks to worn, changed, and discarded if necessary.]

[The Queen (1954), and Queen and Owl in Tree (1954). Rather than a truly egotistical stance, both of these paintings, like all of her works where she takes on the role of queen, are a playful reference to Abercrombie’s nickname of “Queen Gertrude” among her Chicago friends.]

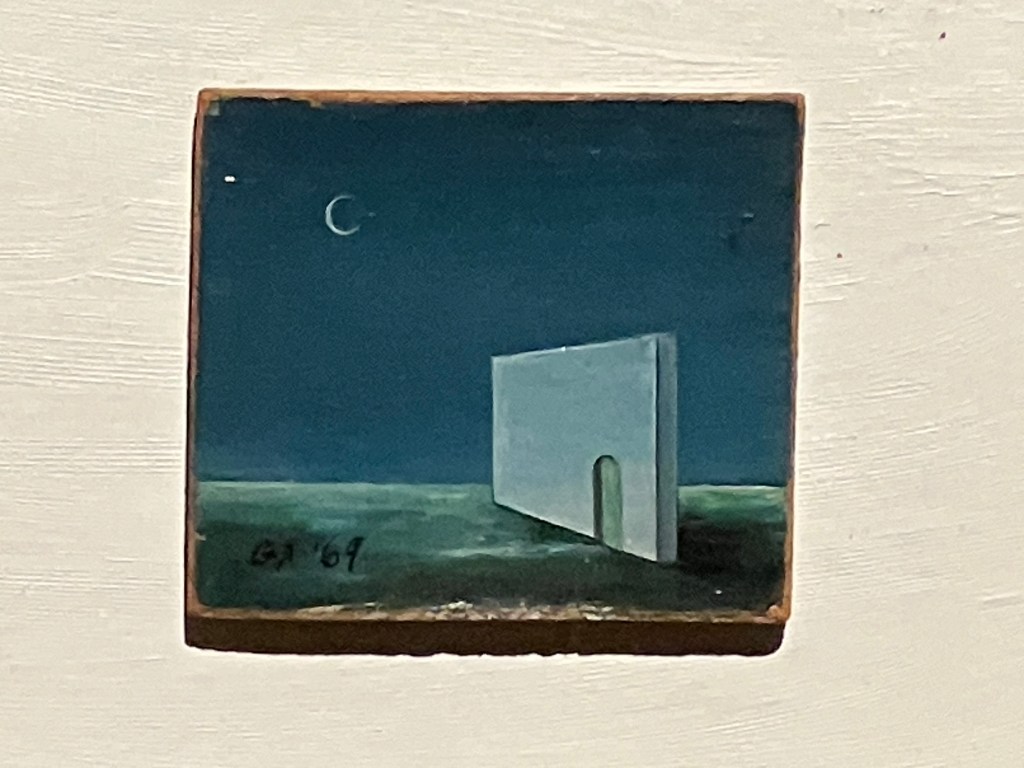

Abercrombie’s paintings are full of recurring motifs and figures, and one of the benefits of an exhibition of this scope (two whole wings of the Scaife Gallery) is to see how these patterns are used and reused throughout her oeuvre. Cats, dominoes, chaise lounges, trees, pyramids, owls, giraffes, ladders, shells, eggs, and a strange man with a striking resemblance to Abraham Lincoln pop up continuously through her forty year career as a professional artist, and while some contemporary critics saw this as a lack of artistic growth on her part, I think that’s a facile approach to her output, because it implies no change in her approach to these motifs when I think there emphatically is. A recurring image in her art that I didn’t mention above is a set of bare building walls that comes from the ruins of an abandoned slaughterhouse in Abercrombie’s childhood hometown of Aledo, Illinois. The clean, bone-like appearance and arresting geometry of the ruins bring an almost Classical, Parthenon-esque beauty to something that is not only abandoned, but the remnants of a distinctly un-beautiful function (death and butchering). The exhibition has three paintings of this singular image, all at different points in Abercrombie’s career, and you can see below how her idea of the ruins changes with her.

[Detail of a photograph of Abercrombie’s first husband, Robert Livingston, and their daughter, Dinah, at the Aledo slaughterhouse ruins (c.1946)]

[Slaughterhouse Ruins at Aledo (1937). Here, you can see the ruins at their most classically realist—fitting for a young artist still finding their unique style.]

[Giraffe House (1954). Whereas here, Abercrombie is fully established in her liminal, surrealist style, and the slaughterhouse ruins become a landscape for her motif giraffes and crescent moons. In her dreamscape, animals are returned to an animal-centric building, but rather than as a location of death, the slaughterhouse becomes a home, and rather than livestock, its inhabitants are whimsical, wild giraffes. Abercrombie continues to repurpose and recontextualize this remnant of labor and everyday life into something that is Art (much as Gala Porras-Kim was doing in her Forum pieces).]

[Wall with Moon (Doorway) (1969). At the end of her artistic career, Abercrombie returns one more time to slaughterhouse, pared down to a single remnant wall and abandoned once more. Struggling with alcohol-related medical issues and depression, as well as arthritis that kept her from being able to paint, the overcast day of her original painting has turned to night, and the landscape has emptied, leaving the seemingly eternal ruins. But the style of this painting fittingly feels like the mature marriage of the more concrete realism of her early work and the hyper-surrealism of her heyday.]

Changing tastes and the usual lack of investment in the legacies of women artists left Abercrombie’s work on the outside of modern museum art for several decades following her death in 1977, but as CMOA’s exhibition shows, her oeuvre is starting to be reevaluated not only alongside surrealists like Magritte and Dalí, but in her rightful place in the 20th century American art movements of which she was such a part as a contributor, muse, and artistic patron. Her paintings are deceptively simple on the surface, but there are so many minute details—objects, paintings within paintings, ideas—that she has richly earned this second look. And speaking of second looks, I don’t know if CMOA has ever put on an exhibition whose art required me to lap the offerings twice in one visit, even at my leisurely viewing pace. I walked both galleries once, took a lunch break, and felt compelled to go back and lap them again to fully appreciate what I was seeing. And I bet if I went back, there would still be new things for me to notice—a positive endorsement if I’ve ever heard one. If you’re in the greater Western Pennsylvanian area, this showing stays on view until June 1st, and I highly recommend checking it out. After that, it is moving to its sister-exhibitionist, the Colby College Museum of Art up in Waterville, Maine, if any east coasters feel like making a drive north for it. And if you have $1k burning a hole in your pocket, like my bane, the snuff bottles, a whole bunch of Abercrombie works are for sale on eBay. Just watch out for all of the cheap AI copycats trying to steal her look😉

[I can tell that some of you didn’t believe me about the Abe Lincoln guy, so here’s The Visit (1944) to prove it. Also, everything I know (and anything I’ve subsequently forgotten) about jazz I learned in the most popular undergrad humanities course at the University of Pittsburgh, History of Jazz, then still taught by the incomparable Dr. Nathan Davis. Not to be confused with the second most popular undergrad humanities course, Vampire: Blood and Empire. But both of which feel very Abercrombie-coded🧛🏻]

Leave a comment