Blessings on thee, dog of mine,

Pretty collars make thee fine,

Sugared milk make fat thee !

Pleasures wag on in thy tail —

Hands of gentle motion fail

Nevermore, to pat thee !

- from “To Flush, My Dog” (Elizabeth Barrett Browning)

This week, I wanted to take a look at an interesting literary subgenre: books about animals told by animals. Now, books with animal narrators are a staple of children’s fiction, but they aren’t confined to juvenilia. The idea of knowing what an animal is thinking transcends age groups, and there have been many works aimed at an adult (or all-ages) crowd for as long as we’ve been telling stories. Traditional folktales like Aesop’s fables and the Reynard cycles are the obvious precursor to this genre in the modern novel, but many writers have tried to elevate the subject past stories about animals to stories by animals.

Probably the most famous animal autobiographical novel is Anna Sewell’s 1877 novel, Black Beauty. Beauty is an English horse living in the contemporaneous mid-19th century, narrating the events of his life to an invisible audience. Although now squarely considered a children’s book, due to its subject matter and digestible prose style, Sewell originally intended the novel for an adult audience. Rather than animal folklore, Black Beauty’s truest literary predecessors are the 18th and 19th century social reformation works of writers like Samuel Richardson and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Indeed, Black Beauty is often called “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin” of the early animal rights movement, and, uncomfortable parallels between the treatment of animals and human slaves notwithstanding, both novels had the similar goal of raising public consciousness toward how a societal underclass was being mistreated. Beauty’s story was meant to show how badly many horses were dealt with in a world where they were still largely working animals, and to push for both cultural and legislative changes for them. Beauty is an obedient horse who wants to please his owners, but Sewell is careful to show that “bad” horses like his friend, Ginger, are the way they are because a cruel and often stupid humanity made them that way. As Stowe shattered the myth that being a “good” slave would protect Black people from harms inherent in the system of slavery, Sewell has her “good” protagonist suffer many of the terrible vicissitudes that befall his “bad” comrades through bad luck and worse owners.

Because of this underlying authorial focus on education and reform, Black Beauty is also probably the least verisimilitudinous of the modern animal autobiographies in terms of narrative tone. Beauty, while not always understanding everything around him, has a very “human” voice and general grasp of the world around him. He has to become accustomed to human notions like trains, fashion, and alcohol, but he understands what a train is, and that drinking alcohol leads to drunken behavior. Incidentally, Sewell making sure to have a subplot of a good character driven to death and ruin by alcohol aligns Black Beauty with the other major reform novels of the day, which were overwhelmingly focused on the temperance movement. A great example of likeminded social movements piggybacking off one another.

In addition to being the most famous, Black Beauty is often called the first fictional animal autobiography, but it is beaten by at least fifty years to that punch by the German Romantic and proto-surrealist, E.T.A. Hoffmann. Hoffmann, best known as a short story writer in our century—the plots of The Nutcracker ballet and the original Sandman come from his short story collections—was also a prolific composer and novelist in his own time. One of the last novels he wrote during his relatively short life was a fictional autobiography of a young cat named Murr, The Life and Opinions of Tomcat Murr (Lebens-Ansichten des Katers Murr). Based on Hoffmann’s own cat of the same name, rather than a story meant to edify like Sewell’s Black Beauty, Murr was written as a playful send-up of self-important contemporary Continental biographies and as a biting class satire. Instead of a creature reciting its story to an unseen audience, Hoffmann creates the humorous framing device that the clever Murr, raised in a scholarly household, has taught himself to read and write, and has copied out the novel you are reading in his own hand. Unlike the human-sounding Beauty, Hoffmann tries to give Murr a distinctly feline characterization. Murr attempts to do justice to his education by being modest and objective about his life, but often he can’t help but act cat-like and give into preening and self-aggrandizement.

The problem for Murr, and arguably Hoffmann’s readers, is that, being a cat, Murr must use the materials at hand to compose his opus. As a result, half of Murr the novel is the protagonist’s autobiography, but the other half is a biography written by Murr’s fictional owner of his friend and mentee, the equally fictional court composer Johannes Kreisler—the obverse pages of which Murr steals for his writing material. The fake publisher of Murr’s writing decides not to separate the works out, so the novel veers wildly between the aristocratic setting of Kreisler’s story and the bourgeois misadventures of Murr in town. Aside from his erudition, Murr experiences life in a very feline manner—he has a frienemy situationship with a dog belonging to one of his master’s friends, he gets caught stealing sausages from merchants, and has numerous amorous escapades, including almost falling in love with his own daughter. By contrast, Kreisler’s comedy of manners among the nobility is probably less immediately interesting to a modern reader than the mischievous Murr, but the whole idea is so weird and arresting that I still thought the whole thing was worth reading. More than liking one half of the book over the other, the real letdown of Murr is that it is incomplete. Hoffman intended to write a sequel to continue the story, but his muse, his own Murr, died while he was completing the first novel, and he confessed to friends that it left him without the heart to keep going with the idea; and the author’s own death within two years of Murr’s publication left no opportunity for his loss to heal.

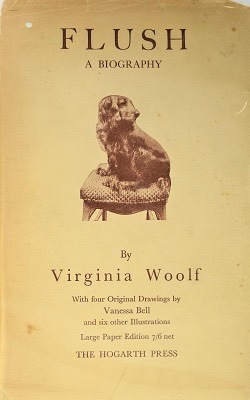

Moving out of the 19th century into the 20th, even the serious, realist writers of the times could be caught under the spell of the animal novel. Much in the way I described myself in my last entry, English modernist author Virginia Woolf was looking for a less demanding outlet after finishing the exhausting process of writing her 1931 novel, The Waves (my personal favorite of hers, btw). Like Hoffmann, taking some inspiration from her own cocker spaniel, Pinka, she embarked on a novel based on the life of England’s most famous member of the breed: Flush, a cocker spaniel owned by 19th century poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning and subject of two poems (“To Flush, My Dog,” and “Flush or Faunus”) and a host of letter anecdotes by the writer. Unlike the other works we’ve discussed, Flush is a biography written in an omniscient third person, rather than first person, and while the subject of mixed reviews since its publication for its “frivolous” topic, it bears all the hallmarks of Woolf’s more “serious” fiction including her stream-of-consciousness narrative style and subtle feminist critique.

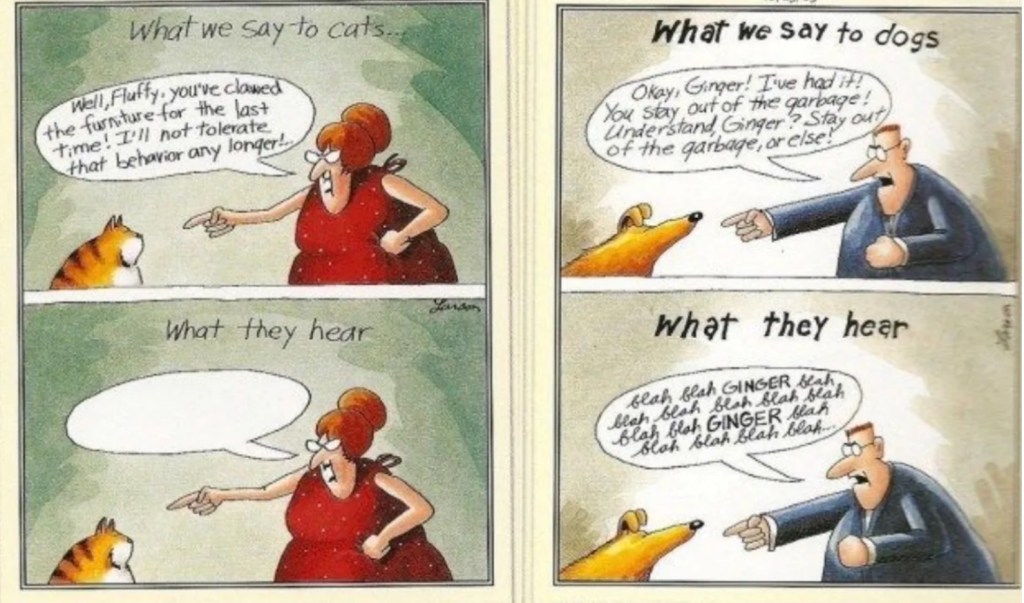

Like Hoffmann does with Murr, Woolf attempts to imbue her subject with appropriate canine sensibilities, particularly in regard to his sense of smell, the main venue through which Flush experiences the world. And in a much more modernist, blended way, Woolf takes Hoffmann’s idea of a dual human/animal biography to its logical conclusion by making Flush’s story a covert biography of Barrett Browning as well. By exploring the relationship between dog and invalid mistress, Woolf can ruminate on the expanses and limitations of art and relationships. Flush and Barrett Browning are devoted to one another, but they can never fully understand each other, divided as they are by a world where one lives in the senses and the other in words. The second of Barrett Browning’s poems, “Flush or Faunus”—recounting an episode where the poet was startled while crying by Flush’s face suddenly next to hers, and she momentarily mistakes him for the satyr god—is illustrative of this vale of un-recognition between humans and animals, as is Woolf’s unwillingness to fall into the first person for her canine protagonist.

Lastly, to bring us full-circle, we return to horses and the first person animal autobiography in English author Richard Adams’ 1988 novel, Traveller, about Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s most famous war mount. Adams, unlike some of the other writers we’ve discussed, is not only not a stranger to animal narratives, it is what he is best known for. His most beloved novel is the children’s classic, Watership Down, the only story about rabbits to traumatize kids more than when The Velveteen Rabbit taught them about scarlet fever and that their toys were alive. While Watership Down is a sort of modern fable told in third person, Traveller, on the other hand, feels like a culmination of the hundred and sixty-odd years of the genre of personal animal autobiography we’ve been exploring.

Eschewing the anthropomorphism of Black Beauty for the attempted realism of Woolf, Adams’ Traveller is often, and occasionally delightfully, misinformed about the human world around him. As a young horse, before he is sold to Lee, he hears about something called “The War” that everyone is very excited about, but he never learns what it means and therefore fails to understand that the thing he experienced with Lee was the war, expressing regret at the end of the book that he “never got to see it.” In another example, he only knows of “Richmond” as the name of Lee’s other warhorse (who Traveller doesn’t like), and he is therefore indignant and baffled every time Lee or one of his commanders insists that they “must protect Richmond.” Adams even attempts some of Woolf’s covert social commentary by having Traveller believe that Perry and Meredith, Lee’s enslaved valets, are actually Lee’s commanders, as they are the only people whose orders (to eat, to sleep, etc) that the horse sees his master obey. And like Hoffmann’s attempt to inject a practical audience for Murr into his story beyond a fourth-wall readership, Adams’ Traveller is depicted as recounting his life to his barnmate, Mildred Childe Lee’s real-life cat, Tom the Nipper. And to continue Woolf’s conversation about cross-species mutual intelligence, Adams makes it clear that horse and cat don’t always understand one another any more than Traveller can plumb the depth of the human experience.

So as you can see from even this rather basic rundown, anthropomorphic autobiographies have often been treated as intellectually insubstantial and fit for little except as a stepping stone for juvenile readers into the world of adult literature. But this is an overly simplistic view of both their history and the texts themselves. For two hundred years, writers have been using the deceptively fun vibes of cute, talking animals to do everything from provide incisive social critique all the way to stylistically revolutionizing the novel as an art form. The animal fable is the beating heart of human storytelling, and that means there’s no reason to mechanically shun the modern anthropomorphic novel as something lesser-than due to their subject matter. Because just like their ancient predecessors, they might be the truest mirror of humanity that we have.

Leave a comment