“In an artless tale, without episodes, the mind of a woman, who has thinking powers is displayed. The female organs have been thought too weak for this arduous employment; and experience seems to justify the assertion. Without arguing physically about possibilities—in a fiction, such a being may be allowed to exist; whose grandeur is derived from the operations of its own faculties, not subjugated to opinion; but drawn by the individual from the original source.” Mary: a Fiction, introduction/advertisement

"It's not true," I snapped, furiously blushing all the same.

"In action? Of course not," he scoffed, as if I was being deliberately obtuse. “But in word?" he asked, leaning forward. "In his heart? In yours?" - The Flight of Virtue, chapter 29

Content Warning: The lives of Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley are intimately linked with suicide, suicidal ideation, and mental illness, as well as a certain amount of romanticism connected to suicide emblematic of the larger culture in Europe during the late 18th century/19th century. If this is a difficult topic for you, I recommend skipping this post. And if you are struggling with these kinds of thoughts, please know that you are too important to this world to do harm to yourself. Life can be incredibly hard, but it will be worse without you❤️

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

This week, I wanted to return to Flight of Virtue player Mary Wollstonecraft and focus on her less well-known fictional output, Mary: A Fiction (1788), and Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman (1798), as well as do a compare/contrast between those novellas and her daughter Mary Shelley’s equally lesser-known Matilda (1819). All three of these works were being written on the cutting edge of contemporary literature by two unconventional women authors at a time where the 19th century vision of the sentimental “lady writer” was already calcifying against the type of radical proto-feminism that the Marys Wollstonecraft were crafting. Caught in a culture that would continue to resist their ideas for another century, these tragic novellas are a mother and daughter, separated by a scant generation, grappling with the limitations of early European feminism and the individualism of the Romantic movement to uplift either of them, and what hope could be stolen from a world that was rapidly changing, but not for them.

Although I briefly sketched out her life in the previous entry I linked above in her name, for those who don’t feel like backtracking: Mary Wollstonecraft was born in 1759 into a middle class/lower gentry English family, and although she would receive very little formal education, she would become one of the premier philosophical writers and thinkers of her generation. Passionately concerned about the societal limitations placed on women in the late 18th century, limitations that often kept them in ignorance and poverty, Wollstonecraft was arguably the first true Western radical feminist. She advocated for women’s education and legal reform under the law, as well as most controversially, the abolition of traditional marriage in favor of a secularized partnership of equality. Her seminal nonfiction treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, remains a cornerstone of modern feminist theory and is the forerunner of other major European feminist texts like Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex.

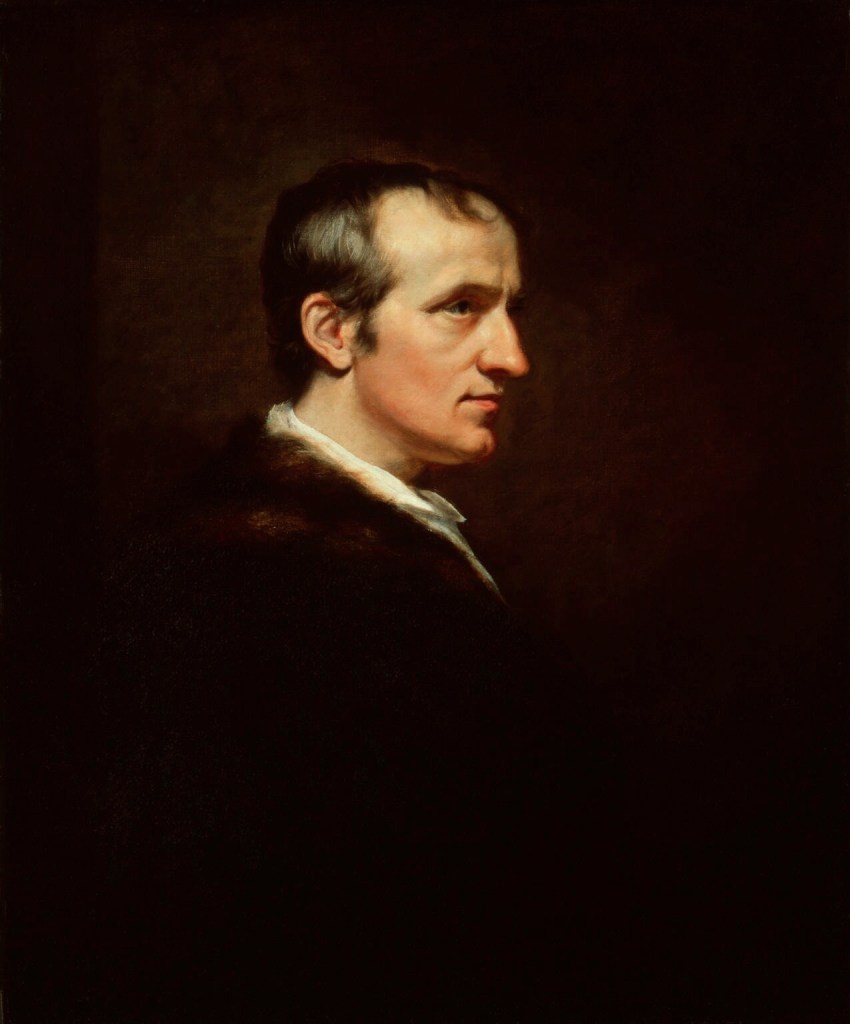

Unlike many male Enlightenment philosophers, Wollstonecraft was equally passionate about practicing the ideals she advocated, at particular cost to her as a woman oppressed by the cultural systems she was attempting to dismantle. Her domestic partnership with American entrepreneur Gilbert Imlay (called an “All-Time Great Historical Douchebucket” by modern feminist scholar Sady Doyle) was beyond the pale of respectable society, even in Revolutionary France where it was happening, and her child from the relationship, her elder daughter Frances (Fanny), was considered illegitimate. Worn down by Imlay’s ultimate lack of feminist allyship (refer back to Doyle’s assessment of him) and the accompanying mental breakdowns it caused, by the time Wollstonecraft found a true ally in English philosopher William Godwin, she (and him) capitulated to cultural hegemony and shamefacedly married in March 1797 when Wollstonecraft found herself pregnant again. On August 30 of the same year, Wollstonecraft gave birth to her second daughter, also named Mary, but was dead of postpartum septicemia eleven days later. Born too early for both her ideas and gynecological germ theory, Wollstonecraft’s intellectual legacy would largely be buried for a century while the rest of the world caught up to her.

While early 19th century society labeled her as nothing more than a mentally ill nymphomaniac, Wollstonecraft maintained a place of honor among radical thinkers in the post-Enlightenment that was rapidly pivoting into the European Romantic movement, which favored individualism, and the moral superiority of beauty and intuition over the more detached intellectualism of the Enlightenment. What both movements shared was Wollstonecraft’s belief in the decayed nature of conventional morality and her rejection of social conventions. And while not entirely won over by Romanticism, William Godwin’s fervent commitment to Wollstonecraft’s work and memory saw him intersect with the movement as he continued to promote her legacy in his own house and among the (mostly unreceptive) public at large.

However, as radical on gender issues as he was, Godwin was still colored by his times, meaning that he had little interest in giving up his own work and writing to care for his extremely young orphaned daughter and stepdaughter. Incidentally, this was something even Wollstonecraft struggled with him about while she was still alive, proving the so-called “second shift” for working women has always been an issue that has plagued feminist equality. Godwin’s solution was the traditional one: he remarried and stuck the new Mrs. Godwin (also annoyingly named Mary) with the girls, in addition to her own illegitimate daughter Clara that she brought into the relationship. That said, Mary Jane Clairmont Godwin also participated in her husband’s intellectual life and helped to run his publishing house as well.

This chaotic, unconventional household is the one that young Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was raised in. Singled out by her father as the most intellectually gifted girl, William Godwin attempted to give his daughter the sort of informal rigorous schooling advocated by her late mother in Vindication, much in the way that Aaron Burr tried to use Wollstonecraft’s theories to raise his daughter, Theodosia. Having missed the opportunity to meet his idol Wollstonecraft, Burr would in fact spend a good deal of time in the Godwin-Clairmont household during his European exile in the 1810s, becoming close with all three Godwin daughters—probably to help ease the absence of his beloved Theo. But like Theo Burr, Mary Godwin would struggle both with the continued broader societal limitations on women that no amount of scholastic rigor could surmount, as well as a problematic attachment to her father, stoked by Burr and to a lesser extent, Godwin, using their daughters as emotional and intellectual surrogates for their dead mothers. While Godwin’s remarriage prevented his and Mary’s relationship developing the unnerving psychosexual dimension that the widowed Burr and Theo exhibited, Mary’s often contentious relationship with her stepmother added a competitive element for Godwin’s attention that Theo didn’t have to deal with. A state of affairs that only worsened over time.

As she became a teenager, Mary’s covert rebelliousness ripened into more overt defiance as she struggled against the sort of purgatorial moral code her upbringing had left her in. She was being imbued with radical philosophy, while still being expected to submit to her father’s patriarchal authority, however comparatively benevolent. As a result, she worshiped the memory of the mother she’d never known and took to reading on her mother’s grave both in homage and to escape the distractions of the busy Godwin house. And into this situation, when Mary was fifteen, arrived the twenty year old Percy Shelley, bent on alienating his aristocratic relatives with his reverence for Wollstonecraft and Godwin’s radical politics. Shelley was soon joining Mary in her Goth Girl Reading Hour jaunts in St. Pancras cemetery, activity that, according to tradition, culminated in the married Shelley pledging eternal love to Mary on her mother’s grave and taking her virginity on the same.

For all his unorthodox beliefs, Godwin was not on board when Mary and Percy explained their deal to him, caught as he was between wanting to change gender norms and wanting his daughter to have a more typical social respectability. Undaunted, the young couple bigamously eloped and fled to Europe to escape Godwin, taking Mary’s stepsister Clara (Claire) Clairmont, with them. What followed was several years of bouncing around Switzerland and Italy with Shelley’s friend, Lord Byron, and a rotating coterie of young Romantic radicals seeking varying degrees of beauty, truth, and sexual liberation. Mary was one of the more sexually conservative members of this ménage, in part because she spent most of her relationship with Shelley either pregnant or recovering from a pregnancy, not that stopped him. Shelley would return to fool around with his actual wife Harriet until she finally despaired of him and drowned herself, shortly after Fanny Imlay, being at least emotionally entangled with Shelley’s crowd, overdosed on laudanum. Claire Clairmont might have also had a sexual relationship with him during breaks in her on and off again affair with Byron, though this is disputed. William Godwin disapproved of all of his daughters’ involvement with Shelley, and he and Mary would remain estranged for the early years of her relationship, though they would eventually reconcile enough to resume a professional arrangement where Godwin would remain his daughter’s publisher. But their original symbiosis would never entirely recover and would haunt Mary’s oeuvre throughout her life.

Harriet Shelley’s death allowed Mary and Percy to finally marry for real, but the early deaths of most of their children further eroded their relationship as Mary turned inward and escaped more into her own writing, something that her husband did support her in, even as he hated her new emotional numbness. With the help of his editorial eye, Mary would write her best known novel, Frankenstein, during their travels, only a few years before Shelley’s death in a boating accident in 1822. She would devote the rest of her life to writing, championing the kinds of reforms her mother had sought, and raising her surviving son, Percy Florence, until her death in 1851.

I know that this feels like an exhaustive retread of the lives of these two women to the exclusion of a longer discussion of the novellas I said were the point of this entry, but as many early(ish) English women authors, both Mary Wollstonecraft and Mary Shelley are in part autobiographical writers, and particularly in these three books, they were influenced by their own unusual lives, in addition to the literary milieu around them. Both were writing fiction at a crossroads in the evolution of the art form in Europe, and it shows in their texts. As one would expect, Wollstonecraft is influenced by key Enlightenment works like Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s novels and those of Johann von Goethe, especially the latter’s ubiquitous bestseller, The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774). At the same time, Wollstonecraft’s Mary and Maria would anticipate both the Romantic and Gothic literary movements that would influence her daughter’s writing and Matilda particularly. The Enlightenment would give both women their focus on elevated, “pure” friendship and love between the sexes and the struggles of intelligent women against a culture that saw them as feeble objects, but Romanticism would give these novellas all their Gothic/proto-Victorian sensationalism: false imprisonments in mental asylums, suicides, consumption, and implied incest.

As a holdover from 18th century novelists like Rousseau and Samuel Richardson, as well as her own natural inclination as a political philosopher, Wollstonecraft writes in a much more didactic style even in fiction than would become the fashion during her daughter’s lifetime and our own times. This means that the flowing text of both Mary and Maria will often feel like it’s stopping the plot to preach at you, or characters will elucidate her points to one another like they’re conversing off to the side of the action. For example of what I mean, here’s an excerpt from Maria:

“Alarmed by some indistinct noise, Jemima [a servant who had been recounting her life story to Maria and Darnford, wrongly confined in an insane asylum] rose hastily to listen, and Maria, turning to Darnford, said, ‘I have indeed been shocked beyond expression when I have met a pauper’s funeral. A coffin carried on the shoulders of three or four ill-looking wretches, whom the imagination might easily convert into a band of assassins, hastening to conceal the corpse, and quarrelling about the prey on their way. I know it is of little consequence how we are consigned to the earth; but I am led by this brutal insensibility, to what even the animal creation appears forcibly to feel, to advert to the wretched, deserted manner in which they died.’

‘True,’ rejoined Darnford, ‘and, till the rich will give more than a part of their wealth, till they will give time and attention to the wants of the distressed, never let them boast of charity. Let them open their hearts, and not their purses, and employ their minds in the service, if they are really actuated by humanity; or charitable institutions will always be the prey of the lowest order of knaves.’” – Maria, p. 91

Mary, the earlier novel, is very much the product of Wollstonecraft’s youthful radicalism and has more noticeable autobiographical elements. The protagonist is the daughter of wasteful, ignorant parents, who must teach herself to unlock her native genius, much like Wollstonecraft. Like the author, the character Mary forms an intense bond with a female friend who is of slightly inferior social status, Ann, who is the literary doppelgänger of Wollstonecraft’s friend Fanny Blood, whom Wollstonecraft named her first daughter after. Like Fanny, Ann dies of consumption (the pretty, poetic death) while Mary gains an equally intense bond with a sympathetic male friend whom she has a spiritual marriage with that transcends traditional morals. Mary as a novel feels very much like a feminist Werther clone, everybody has big emotions and Mary contemplates killing herself rather than accepting her (very distant, blandly unfulfilling marriage) to an entirely offscreen aristocrat.

[Goethe’s Werther was a genuine literary phenomenon, spawning an army of written copycats and supposedly just as many actual copycat suicides. Even Napoleon wrote part of a Werther-style novella—I might talk about it one day, but honestly, it’s not particularly good…]

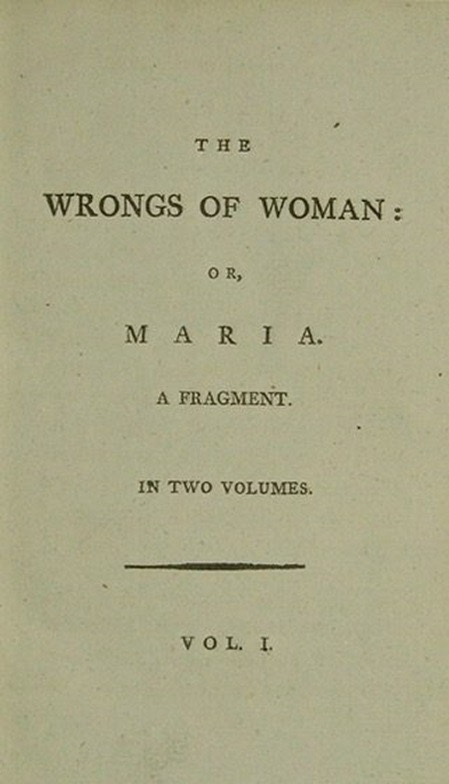

The unfinished and posthumously published Maria, through its alternate title (The Wrongs of Woman) and its subject matter, is in direct conversation with the nonfiction A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and Wollstonecraft’s mature feminist philosophy, despite its much more sensational Gothic trappings. The protagonist Maria is falsely imprisoned in a castle-cum-asylum by a reprobate husband bent on getting his hands on her inheritance. Gone is the inoffensively indifferent aristocrat spouse of Mary, and in his place is the unrepentant rake whom the unjust laws of the land make the undisputed master of our trapped heroine. Even the more heroic love interest, Darnford, isn’t someone Maria can rely on. In the unfinished fragments left by Wollstonecraft at her death, it is revealed that rather than the intellectual soulmate (Godwin) he seems to be, Darnford is in fact Gilbert Imlay, and will abandon the heroine for another mistress in the end. In addition to spelling out the harms suffered by the upper classes of women, Wollstonecraft also uses the figure of Jemima (see the quote above) to illustrate the grinding circumstances that destroy poor women, though Wollstonecraft’s beliefs are not devoid of the more conventional classism of her time. More than the pre-revolutionary sentimentalism of Mary, Wollstonecraft wants the Gothic sensationalism of Maria to underline her points about patriarchal norms, even at the expense of a smoother fictional style.

Conversely, Mary Shelley’s Matilda (sometimes printed as Mathilda), is much more a novel in the traditional sense, in that Shelley isn’t here to teach, but to explore truth through emotion in the strictest Romantic sense. But like her mother’s novels, Shelley is still using fiction to excise autobiography. Where Wollstonecraft is often fictionally torn between her passionate adult relationships (with Fanny Blood, with Imlay, with William Godwin), Mary has the classic Gotho-Romantic duality of father (Godwin) and lover (Percy Shelley). Like the author, the protagonist Matilda’s mother dies in childbirth, and after initially distancing himself, her father then becomes intensely involved with her. Eventually, the father confesses that he’s incestuously in love with Matilda and kills himself as a result. Although neither of them ever acted on her father’s forbidden attraction, Matilda feels that she is spiritually polluted for having produced such emotions in her father and secludes herself from society as a result. In spite of this, she becomes friends with Woodville, a poet with his own tragic romantic history (clearly Percy), whose feelings she ultimately rejects. After wandering out into the heath overnight, trying to cleanse her soul of her invisible stain, it is implied that Matilda gives herself consumption, which she eagerly encourages in order to purge herself so that she and her equally cleansed father can be reunited in spiritual love in heaven.

As you might imagine, William Godwin was not a fan of this story when Mary sent it to him for publication in 1819. He was so horrified by the incest theme that not only did he refuse to publish it, he refused to return the manuscript to his daughter, despite numerous requests on her part. Only after her husband’s death by drowning, under circumstances eerily similar to the death Mary had written for the novel’s father, did she decide that the manuscript was ill-starred, and she abandoned attempts to publish it. As a result, Matilda remained unpublished until the 1950s, when it was cobbled back together from Godwin and Shelley’s papers.

That said, do I think Godwin’s reaction is the result of a guilty conscience, or that Mary was implying real incest between her and her father? No. But much as I did in Flight of Virtue with the intense and unorthodox relationship between Aaron Burr and Theo, I think that Mary is toying with the sand gain of truth inside the sensational pearl of father-daughter incest. After all, her heroine Matilda feels the guilt of the sin without actually committing the sin. Like the Burrs, I’m guessing there was an element of emotional incest between Mary and Godwin, sublimated into a mutual dependence that she recognized was unhealthy for both of them. Arguably Theo Burr avoided the crisis Mary had in her relationship with her father (when she ran off with Shelley) by choosing a husband who would not function as a rival to her father (the inoffensive Joseph Alston), but as a result, the Burrs never weaned themselves off their dependence. When her elopement caused estrangement between them, Mary was forced to confront what severing that emotional attachment might mean. It’s interesting in 1819, before Percy’s drowning, Mary could only imagine that separation resulting in death.

All three of these novellas are arguably too short to be their authors’ best work. The characters aren’t very three-dimensional, and the plots too sensational to be interesting on their own. But with the additional context of both their writers’ lives and the restrictions they were fighting against, you come to understand that these aren’t the midcentury potboilers, using taboo subjects merely to titillate. Instead, you see that both Marys used what would be largely ghettoized as the conventions of “ladies’ fiction” to explore injustice and the psychological effects of being an oppressed class in an unequal society while in the shadow of men who, while sympathetic, were still subconscious perpetuators of that inequality. It’s easy to see how, in fiction, love and hate could become warped dualities, and the masks that separate our relationships could become harder to parse. The even more difficult task for those of us two hundred years on is to discern if we’ve really made as much progress toward their ideals as we think we have.

Leave a comment