Caroline: I had this dream...

Lloyd: Do we have to do dreams?

Caroline: I'm in this restaurant, and the waiter brings me my entree. It was a salad. It was Lloyd's head on a plate of spinach with his penis sticking out of his ear. And I said, "I didn't order this." And the waiter said, "Oh you must try it, it's a delicacy. But don't eat the penis, it's just garnish."

Dr. Wong: Lloyd, what do you think about the dream?

Lloyd: I think she should stop telling it at dinner parties to all our friends. - The Ref

“I can’t believe I’m telling you this, but I’ve had a couple drinks and… oh my God!” – Lady Gaga, Sexxx Dreams

There are many, for a lack of a less pejorative term, pseudosciences that I wish were real because I find them interesting/entertaining, but over which I can’t quite let go of my skepticism to actually believe in. Astrology and tarot are examples, but of a longer standing interest to me in a similar vein is oneiromancy, the interpretation of dreams. I understand (apparently) that a lot of people find dreams boring—especially other people’s—but I have never been one of them. The mind is a strange and complex place, and I’ve always had an interest in what it gets up to when consciousness isn’t around to direct things.

[Even if I’m not the lucky sort of person who gets usable inspiration from their dreams. This is a 1824 illustration of Giuseppe Tartini receiving his famous Violin Sonata in G minor (the so-called Devil’s Trill Sonata) from His Satanic Majesty in a dream in 1713.]

I think that I can trace this fascination back to an illustrated dream dictionary I used to thumb through at my grandparents’ house during long parties as a child, captivated by the idea that dreams might mean something. It was an odd book for my grandparents to own, but my grandmother was someone who sometimes recounted an odd dream or two, though whether she really believed in the dream dictionary I don’t know.

[One of my grandmother’s most famous dreams in our family was one she had right before my mom had me, where she dreamed my mother had given birth to a cat.]

As I said, I don’t really believe in dreams as prophetic, but I do find them interesting to sift through, and I like hearing how other people dream. For example, my mother rarely remembers her dreams, while my wife has permutations on basically the same dream almost every night (she’s a “trying to pack up and leave X place” kind of person), while a friend says they only dream in black and white. Meanwhile, I remember a lot of my dreams, which are in color, and though I, too, have frequent dreams like my wife’s, mine are definitely coming from a place of anxiety, whereas often hers are more of a nightly Inception-style puzzle problem.

[She also dreams about being able to fly a lot, which I never do.]

Most of my dreams I can trace to worries or preoccupations in my waking life, but unlike Tartini, I never dream about my creative works completed or in progress (my guess is that my brain uses the night to take a break from constantly thinking about those). Three months living on a cruise ship for Semester at Sea has apparently left me with permanent recurring dreams about being on a boat, which I think is unusual for this period in history, but as we’ll discover, was much more common in the past when more people were involved with ships and sailing. The closest I’ve ever had to a prophetic dream was I kept dreaming about having three cats instead of two for the year before we rescued our third cat, but since his passing, I’ve never had dreams like that anymore. I tend to dream about people and places that I can’t return to more than things in my current life, which doesn’t generally bother me—though I had a weird stretch this summer where I had three dreams in short succession involving a school friend who had died in a tragic accident years ago, and since I had never dreamed about her before and we hadn’t been so close as to seemingly warrant this, I had to spend the day after the third one convincing myself that it had no deeper meaning. And I’m sure if I polled every person reading this, all of you would have many variations on these dreams, as well as a host of completely different experiences.

But another thing I find interesting about dreams and thinking about them is that rather than being just a hobby for navel-gazing weirdos, it is something relatively universal across our history as a species. Much like beliefs in divinity, humans have always been drawn to dreams because they are such a bizarre evolutionary quirk—that part of our brain’s physiological and emotional health is tied to these vivid hallucinations we experience while we sleep. And considering how much attention dreams and dreaming have been given, we still don’t fully understand why we do it. I suspect much of that ambiguity comes from the deeply individualistic nature of dreaming, as I tried to illustrate above. How can you categorize something that is both so ubiquitous and so personal at the same time, especially across time and cultures? These are not just questions that modern neuroscientists and occultists are pursuing, these were the exact same questions ancient people were asking. So today I thought we’d look into that a bit through the lens of the most prominent and complete dream dictionary to come out of the premodern world, Artemidorus’ Oneirokritikon to discover what it says about dreamers in the ancient Mediterranean, and perhaps, even about ourselves.

Like many of the ancient authors we’ve met here, we don’t know very much about Artemidorus of Daldis outside of what he’s willing to tell us in his one surviving treatise, the Oneirokritikon (The Interpretation of Dreams), but compared to the other various ancient fiction writers and rhetoricians I’ve talked about, Artemidorus is trying to set himself up as a credible authority, so he probably has less incentive to make up biographical details unrelated to his expertise. Based on the other oneiromancy sources he cites and his apparently contemporary address of parts of his book to Cassius Maximus, reasonably believed to be the late 2nd century CE rhetorician Cassius Maximus Tyrius (Maximus of Tyre), Artemidorus is also thought to have lived in the late 2nd century/early 3rd century CE. Unsurprisingly, given his name, Artemidorus was from the Greco-Lydian city of Ephesus on the western coast of Asia Minor (modern Turkey), patron city of the goddess Artemis and home to her most celebrated temple.

[Statue of Ephesian Artemis from the 2nd century CE, still sporting the goddess’ ancient Asian form, which emphasized her older links to fertility as well as virginity. We still aren’t sure whether the orbs on her chest are multiple breasts or representative of bull testicles, but both connect her to her older role as a matriarchal divinity.]

But the sharper eyed among you might be wondering why I called him “Artemidorus of Daldis” if he was from Ephesus. Well, Artemidorus gives his reasoning to Cassius Maximus himself: “As for the way I style myself as the author, do not be surprised that I have styled myself ‘Artemidorus of Daldis’ and not ‘Artemidorus of Ephesus’, as I often did in the books I have before now written on other subjects. Ephesus has come to be renowned in its own right and to be fortunate in the many distinguished men who can broadcast its name, whereas Daldis is a small and not very notable town in Lydia, which has remained in obscurity up to our time. So I am attributing this work to my native town on my mother’s side as a thank-offering for my nurture.” (Oneirokritikon, 2.70.13). So we see that Artemidorus was comfortable enough in his own reputation to “risk” lending some shine to his maternal hometown of Daldis (Δάλδις) on the Lydian-Phrygian border further inland in Asia Minor, over the very famous Ephesus. Aside from this rather touching personal reason, Artemidorus might have also been calling on some divine authorial backup for his dream book, for while Ephesus was the domain of Artemis, Daldis’ patron god was her twin brother, Apollo, god of diviners and prophecy.

[Here is a 2nd century CE coin minted at Daldis, where on the obverse side (R), you can see Apollo (L) playing a kithara.]

Despite what you might be imaging, and as is usually summarized by people talking about ancient attitudes towards dream interpretation, Artemidorus didn’t believe that all dreams were divinely inspired, and he even expressed skepticism that the gods were in any way routinely involved with human dreams. Given this, it might be surprising that he calls on Apollo at all. But you must keep in mind that Apollo’s gift of prophecy isn’t just a means of conveying information about future events, it is an expression of divine truth. Artemidorus is calling on Apollo as much to bolster his claims to explaining the techniques of oneiromancy truthfully as he is to appeal to the oracular god. Additionally, Apollo’s epithet in Daldis was Mýstēs—“initiate” (the root of the English word mystery). This word in Greek often referred specifically to the initiates of the Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Persephone, but Apollo’s varied roles as sun god, agricultural protector, holy physician, and prophet of cosmic truth tied him to the cycles of life and death presided over by the mystery cults, which may be why he was connected to them by the Lydians.

We also know that Artemidorus was married at least once, as he recounts a disagreeable personal dream where he was physically beaten by his wife (2.48.3)—incidentally, Artemidorus considers it generally inauspicious to be beat up by anyone the dreamer has authority over (as a man would have had over his wife in 2nd century Ephesus). But it is equally bad to be the one beating your wife—that means she’s committing adultery (2.48.1-2). And we know he had at least one son, also named Artemidorus, because books four and five of the Oneirokritikon are addressed to him instead of Cassius Maximus, in hopes by the author that the younger Artemidorus might follow in his footsteps as a professional oneiromancer.

[Artemidorus Sr. also admonishes his son to keep these books secret (Bk 4, preface, 4), so as not to reveal all their trade secrets—oops😬]

One of the more interesting things about Artemidorus as an oneiromancer is that he both claims to have traveled widely over the Roman empire to study various cultural approaches to oneiromancy in Greece, Italy, and Egypt, and he is clearly intimately familiar with the leading written oneiromanic sources of his day (Alexander of Myndus, Antiphon, Artemon of Miletus, Aristander of Telmessus, Demetrius of Phalerum, among others—many of whose works primarily survive as references in the Oneirokritikon). And yet he in no way a slave tradition. He often disagrees with other oneiromancers’ conclusions, and he isn’t afraid to offer his own interpretations based on personal, practical experience. Artemidorus also, very unusually, isn’t above learning from the kinds of popular fortune tellers (“diviners of the marketplace”, as he calls them) operating in every town and village in the empire (Bk 1, preface, 4). Of course, some he’ll denounce as frauds and swindlers, but he’s a big believer in, as I said, hands-on experience with clients over what you can merely learn from a dream book.

And much like ancient astrologers, that’s really the crux of the Oneirokritikon and Artemidorus’ advice for aspiring oneiromancers: a good oneiromancer uses real world facts and information to help their clients. Although the bulk of the Oneirokritikon is a straight up dream dictionary with scenarios and what they mean, Artemidorus is insistent that a specific scenario can be generalized, say, as auspicious or inauspicious, but its truest meaning is dependent on the person who dreamt it. There are plenty of scenarios that he illustrates where the social status of the dreamer (rich/poor, slave/free) fundamentally changes his interpretation. To pull an example that gets a lot of ink in the Oneirokritikon but I’m guessing is less common now, to dream of being crucified is generally auspicious for a slave (because a crucified person is no longer subject to anyone), but inauspicious for the rich (because a crucified person is stripped naked) (2.53.1-2).

Artemidorus also stresses the importance of cultural context. Entering the temple of a god can signify becoming a priest of that god, or intendant social elevation and wealth (4.49), but if the dreamer is barred from that god’s temple in real life, it could signify calamity. He uses the dream of a woman from his own city, Ephesus, to demonstrate this: the woman dreamed that she entered the temple of Artemis and ate there, but since she was married (and therefore tabooed from the temple in real life), it signified death and she died (4.4). On the other hand, he also points to a similar dream had by an Ephesian prostitute, and although she would have also been forbidden in the temple precincts, for her the dream was a sign that she would soon be freed (pornai were usually slaves) and no longer in sex work (ibid). The dreamer’s waking world reality was crucial for understanding what they experienced in their dreams. It’s this varied approach to interpretation that I think permits Artemidorus’ oneiromancy to straddle the place between art and at least what passed for science in the ancient world. He’s fully aware that sometimes a cigar is just a cigar in a dream, and many dreams are just subconscious manifestations of our current anxieties and circumstances—that’s why he encourages oneiromancers to gather as much information about their clients as possible, in order to sort dreams with additional meaning from run of the mill worry dreams.

As for those of us now, reading Artemidorus and how much you’ll enjoy it is also largely an exercise in the personal. The English translation I read, the 2020 Oxford World’s Classics edition by Martin Hammond, warns in its introduction that many readers might want to read the Oneirokritikon’s books out of order to mitigate the tedium of straight lists of dream scenarios and their interpretations. But I was a reads-the-dictionary kind of kid, and I didn’t mind it in chronological order. The Oneirokritikon isn’t that long and Artemidorus’ prose is, by design, unliterary and straightforward. For me, the real pleasure of it isn’t in finding out what seeing a hyena in your dreams means (lesbians, witches, and twinks, apparently (2.12.14)—sounds like a fun time for someone…), but rather reading Artemidorus’ lists as a window into the lives of generally very ordinary people in the 2nd century Mediterranean.

Because unlike say, Thrasyllus, Balbillus, and the famous court astrologers, Artemidorus concerns himself with regular folks on all points of the social hierarchy. Reading between the lines, you find slaves searching for signs in their dreams that they’ll be freed, men and women looking for clues about their marriage prospects, and the sick hoping that what ails them won’t be fatal. And for all of the dreamscapes tied firmly to a lost past where shipwreck and crucifixion were much more likely problems, you find so many scenarios that have remained unchanged over the millennia. Dreaming about your teeth falling out, being dressed in the wrong clothes, having sex with the wrong person, sports dads stressing about how their kids (sons) are going to do in a competition—some dreams transcend time and place, and reveal our shared (embarrassing) humanity. I think that makes the Oneirokritikon more than just a dream dictionary and Artemidorus more than just a rote cataloguer.

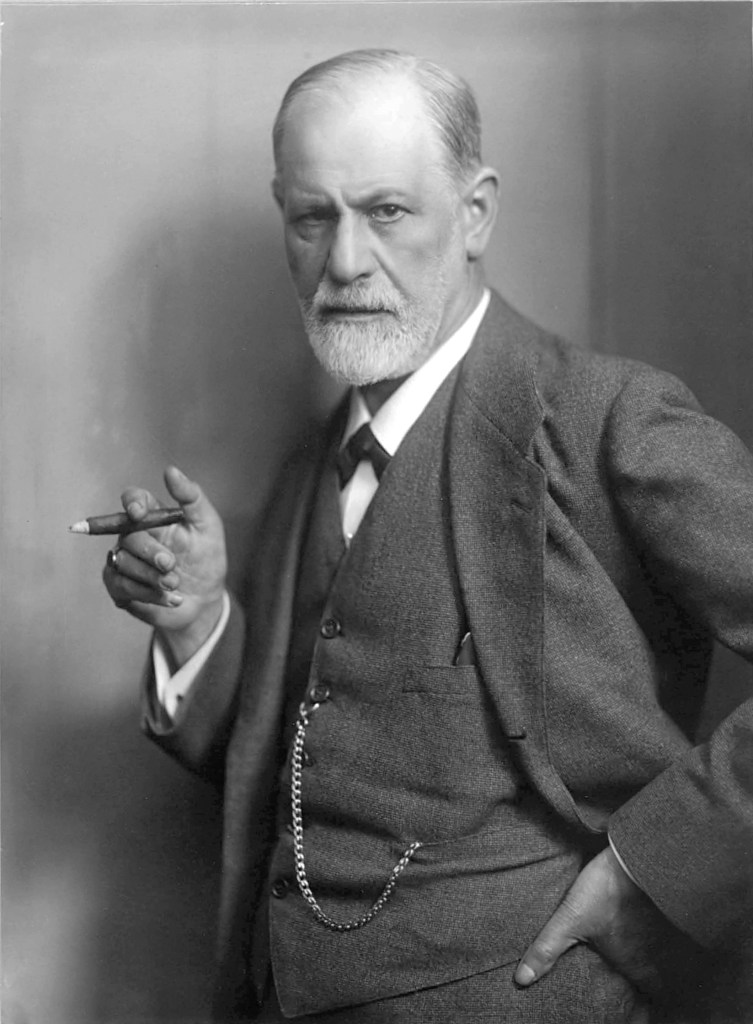

[And for the most part, he says don’t stress out about incest dreams. They’re always metaphorical and usually not even negatively so. But as you might imagine, Freud looooved the Oneirokritikon…]

Leave a comment