I’ve said before that, for good or ill on your folks’ end, I don’t spend a lot of time worrying about analytics here on WordPress. I do my write ups on things that interest me at the time and (try) to trust that some of you will be on board. That said, it’s hard to ignore that the most popular post I’ve ever written (by a stupidly large margin) was my obscure Egyptian gods listical from three years ago, which has become, despite me avoiding the more pejorative adjective of “weird,” the #1 Google search result for “weird Egyptian gods.”

[We did it, Joe!]

But since it’s basically impossible that I’ll run out of obscure Egyptian deities or interest in all things ancient Egypt, I figured that the time was ripe to revive this one for a second round. So here it is, folks—ten more Egyptian gods you probably haven’t heard of for your search engine optimizational pleasure!

10) Ash

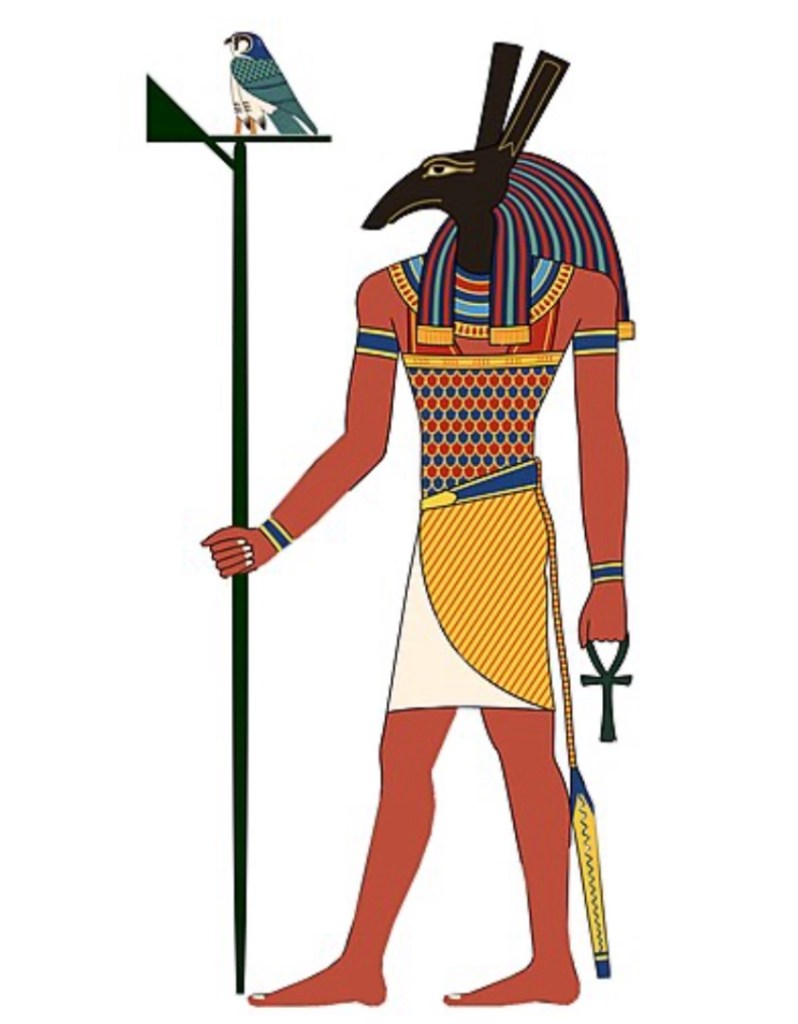

I know what you’re all saying. You’re saying, “Sarah, that’s not an obscure Egyptian god. That’s Set with a Horus plushie on a stick.” But no! This only looks like the Lord of the Red Lands—or maybe it is him? He’s not the Lord of Deception for nothing…

Joking aside, this is Ash, an extremely ancient deity from the predynastic period, who based on his unEgyptian name may have been a foreign import from Egypt’s western border. He was primarily a god of the deserts and their oases, and was most associated with some of the earliest known Libyan tribes, particularly the Libu, from whom Libya derives its name. Indeed, Ash is most often called “The Lord of the Libyans” in texts. Like Set, Ash was dualistic god, and one who was associated with many desert animals such as vultures, lions, hawks, and snakes. However, although they share some spheres of influence, there are points of divergence. They are both desert gods, but Ash isn’t usually a war god in the way Set is, nor does he have Set’s connection to universal chaos (isfet) or the underworld. And while Set is often an oases deity too, this is stronger with Ash, as the latter is also a god of vineyards, something I’ve never heard of connected to Set.

That said, Ash’s conflation with Set, who is also an extremely old god in the Egyptian pantheon, began very early on, unlike many other syncretic Egyptian deities, for whom this process happened much later and therefore during more historic (read: documented) times. Ash himself is referenced as late as the 26th dynasty (664-525 BCE), but most of his heyday appears to be during the predynastic and Old Kingdom, where his name has been found on funerary jars in the necropolis at Saqqara. This is where a lot of the confusion about Set’s origins and powers comes from as well. Was Set an Egyptian god, or a foreign god? Well, it might depend if Ash was a local or an interloper, which we just don’t have enough evidence for either way. I’ve talked several times about Set’s deep roots in the predynastic city of Nebut/Nebyt (Hellenistically, Ombos, and modernly, Naqada), but there is some scholarly thought that Ash may have been the original guardian deity of the city, as one of his other ephitets is Nebuty—literally, “He of Nebut.” So trying to decide which god was first; or whether they were fully concurrent, or later combined, is kind of a chicken and egg problem. But I’m sure that the Prince of Storms would consider two Sets better than one.

9) Heqet

Heqet might be the closest thing to a known god on this list, as she sometimes comes up as one of the “forbidden gummies” in her amulet form.

[Mmm…delicious rocks…]

I’ve also occasionally used her as an unrelated reaction picture here on the blog:

But when we’re being a little more serious, Heqet (sometimes spelled Heket; both from the Middle Egyptian hqt), was the consort of the god Khnum, with whom she shared the responsibility for creating human beings. Khnum would fashion people on his potter’s wheel, and Heqet would place and shape them within the womb. She was also a goddess of childbirth itself, considered the one needed to complete the birthing process, much like the Greek goddess Eileithyia. Unlike the more famous Taweret, who was more a guardian of child rearing, or Meskhenet, another deity involved specifically with childbirth who we’ll get to in a bit, Heqet seems to have been a goddess of the entire fertility cycle from conception through birth. Her animal totem, the frog, was an ancient Egyptian symbol of fecundity and was closely associated with the annual Nile floods, the ultimate fertility metaphor in the Egyptian world. As “She Who Hastens Birth,” Heqet is present during many important birth stories, most significantly, it is she who breathes life into Horus, and is consequently viewed as a goddess of rebirth via the Osirian resurrection narrative. This link between life, death, and resurrection may support the linguistic theory that the Greek goddess Hecate’s name is a derivative of hers, as well as certain frog amulets and markers from the Common Era in Egypt that suggest a variant of her cult was syncretic for a time with Copt Christianity.

8) Dedun

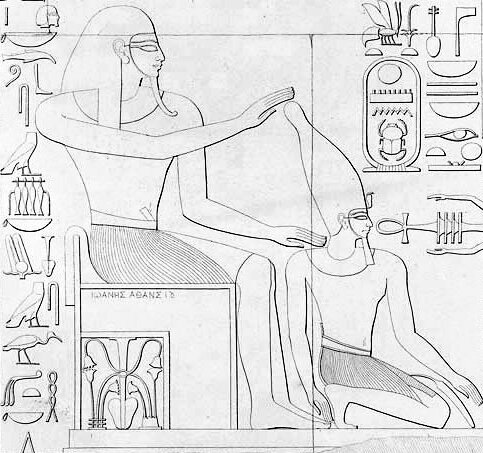

Unlike the uncertain origins of Ash, we know that Dedun (alternatively, Dedwen) was a foreign god synthesized into the Egyptian pantheon, though how deeply that integration was is open to debate. As Ash was the Lord of the Libyans, Dedun was “He Who Presides Over the Nubians,” Nubia being Sudan and Egypt south of Aswan, as well as what would be incorporated in the Kingdom of Kush. Though sometimes depicted as a lion or unspecified bird, Dedun was usually anthropomorphic, and he was primarily the god of incense, a commodity Egypt traded with Nubia for. Because of how costly incense was and the probable Nubian royal monopoly on its sale, Dedun also became a god of wealth and prosperity.

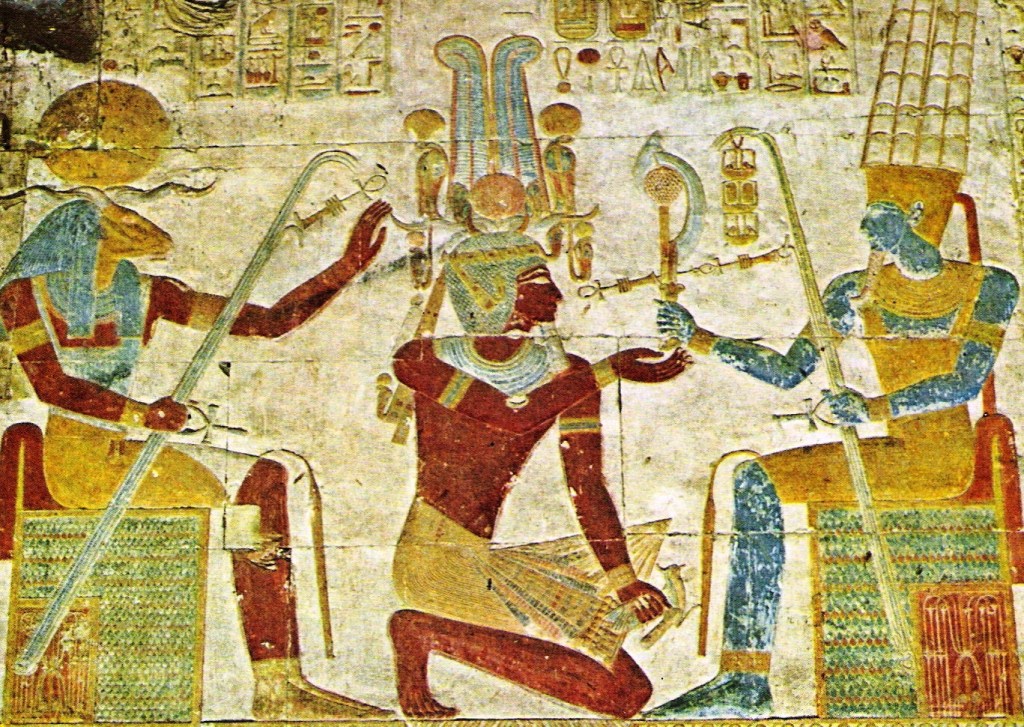

Dedun was mostly a god local to the southernmost cities of Egypt, except during the 25th Dynasty, when Egypt was controlled by the Nubian pharaohs, who obviously promoted his wider worship. This may be when Dedun became seen as the god who provided incense to the other gods, something integral to their service and funerary rites. But Dedun is present in the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts, and the picture above is 18th dynasty pharaoh Thutmose III (kneeling) being crowned by Dedun (seated), so clearly he was present in Egypt before the 8th century BCE. Thutmose’s relief might be symbolizing his military victories over parts of Nubia during his reign, using the royal Nubian patron god’s gesture of approval to signal the moral right of his conquests. The fact that Dedun is crowning Thutmose with the towering hedjet crown of Upper (southern) Egypt, where Egypt and Nubia meet, is also indicative of this.

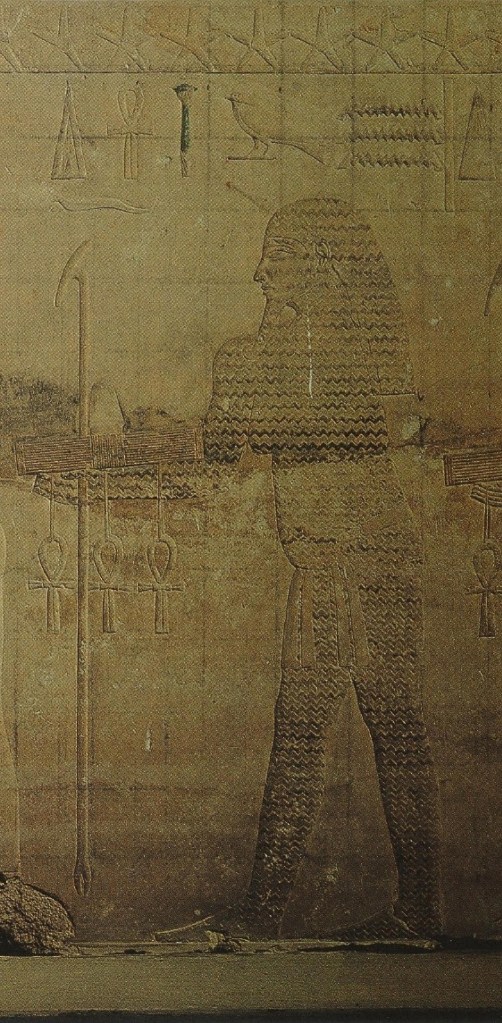

7) Wadj-wer

As he bares a striking resemblance to the androgynous Nile god Hapi, and because he’s covered in little squiggly waves, you might have guessed that Wadj-wer is an aquatic god himself. His name means “Great (wr) Green (w3dj),” and he is often held out as the Egyptian personification of the Mediterranean Sea, which most of the ancient world referred to as “the Great Sea.” However, an alternative viewpoint, based on texts that suggest one could traverse his domain on foot, has led some Egyptologists to believe that Wadj-wer represents the marshlands and lagoons of the inundated Nile Delta, whose vibrant green color during the flood season can be seen from space.

Like the busty Hapi, Wadj-wer is also a fertility figure, their breasts being symbolic of the fecundity and life-giving nature of Egypt’s great river (hence why the relief above shows him carrying ankhs, the symbol of life). Like other personification deities, Wadj-Wer doesn’t have a corresponding mythological presence, but he is an important funerary figure in tomb art, especially from the 5th dynasty (25th century BCE) through the New Kingdom (13th century BCE). This suggests that, like Heqet and other fertility gods, there is a chthonic element to Wadj-wer’s worship, which makes sense in light of the Egyptian belief that water served as a gateway between the worlds and fertility gods’ power to use life force to combat death.

6) Tayt

While many Egyptian gods have rather esoteric reputations, there are some very practical deities, too. One of these is Tayt, the Egyptian goddess of textiles. Clothes are of course important, but from nearly the beginning of its history, the production of superior quality linen was one of the pillars of the Egyptian economy both domestically and abroad, making this otherwise minor goddess far more integral than she might at first seem. This is emphasized by her name, t3yt, literally being the Middle Egyptian word for “garment.” Tayt’s two traditional consorts also reflect strangely minor yet important status. One is Hedjhotep, who is a simple gendered mirror of her as another fabric deity; but the other is Neper, the god of grain—the other commodity staple of ancient Egypt.

[Ironically, Neper also looks like Hapi and Wadj-wer. You can tell it’s him though by the three grains of wheat over his head.]

Aside from being responsible for this key piece of Egyptian mortal life, Tayt was also the goddess who clothed the gods and provided the protection that the cloth nemes headdress supposedly gave the pharaoh. This protective aspect of her powers gave Tayt a maternal relationship with the king, as well as a guardian role in broader Egyptian funerary rites—because what do you think mummy wraps are made of, after all? As a chthonic goddess, Tayt is “She Who Awakes in Peace,” and all of her specialties come to bear in the Duat. She is the expert weaver prayed to so that the deceased has linen offerings that will please the gods, but she is also the motherly goddess who is often shown tenderly swaddling the dead in their mummy wraps in preparation for their rebirth in the West. To tie back to our last entry on the Tale of Sinuhe, part of Senusret’s exhortation to Sinuhe that gets him to agree to return to Egypt is that only in Egypt will Sinuhe be able to receive “wrappings from the hands of Tayt,” i.e., a proper burial. Tayt is as much the mother Sinuhe is coming home to as Egypt itself.

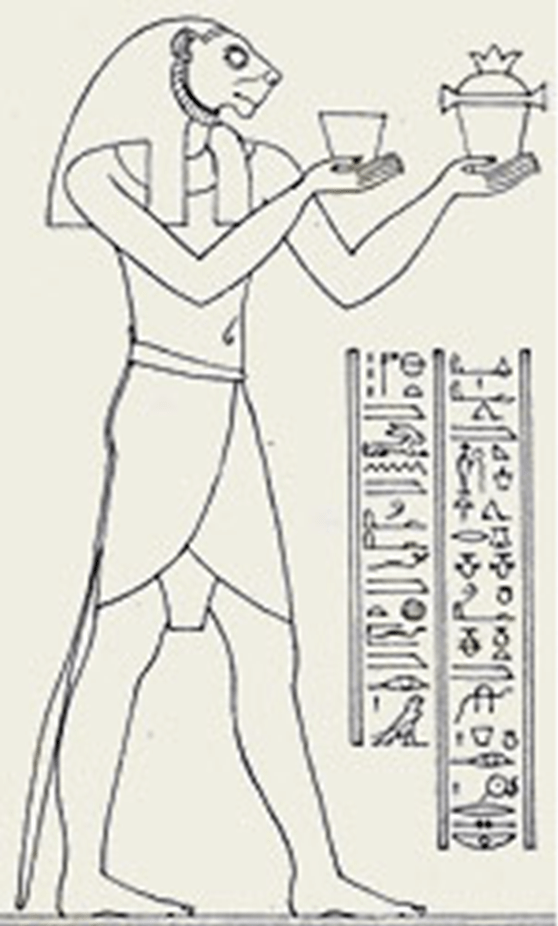

5) Shezmu

Unlike my last list, this one has so far been lacking in violent deities, so I thought next we’d look at the somewhat schizophrenic god, Shezmu. Like many of the gods we’ve been talking about, Shezmu is an old god, one whose worship is most connected to the Old Kingdom (c. 2680s-2180s BCE). Although Wikipedia has a fun illustration of him as a vulture-headed god double-fisting a pair of knives, from what I can best tell, when he was (rarely) depicted, Shezmu was usually a lion or lion-headed man—the default for a violent Egyptian god. Shezmu was the god of blood, “the great slaughterer of the gods, and he who dismembers bodies” in some of the Pyramid Texts, where he is asked to kill even the gods to provide a dead king with the sustenance necessary to survive the dangerous journey through the Duat. But as Set is a dualistic god in the underworld, Shezmu is also a protector of Mesektet, the Night Barque/Bark, the solar ship of Ra, as it traverses the treacherous waters beneath the horizon.

But it should be noted that blood in a ritual context in the Egyptian religion was a contradictory term. Many of the gods’ blood was thought to in fact be red wine, and many temple blood offerings were actually wine instead of animal blood (this is where Herodotus gets the mistaken notion that Egyptians didn’t drink wine themselves, because he thought they held it as divine blood). This jives with Shezmu’s less frightening side as a god of wine and celebration, one to whom songs and dance were offered during the grape harvests. Sometimes this gets translated as it does in a gruesome 21st century BCE funerary text as Shezmu moving a pile of severed heads through his wine press rather than fruit, but the unsettling combination of ritualistic ecstasy and violence is hardly unusual among this class of deity—see half of Dionysus’ mythology. Shezmu’s association with wine pressing in turn links him with oil presses and particularly in later eras, he’s also a god of unguents, which he was seen, not as necessarily the god of perfume like Nefertem, but as the sacred perfumer of the gods and their vintner. In the picture above, these are the items he is likely holding in his hands: a cup of wine and a jar of oil.

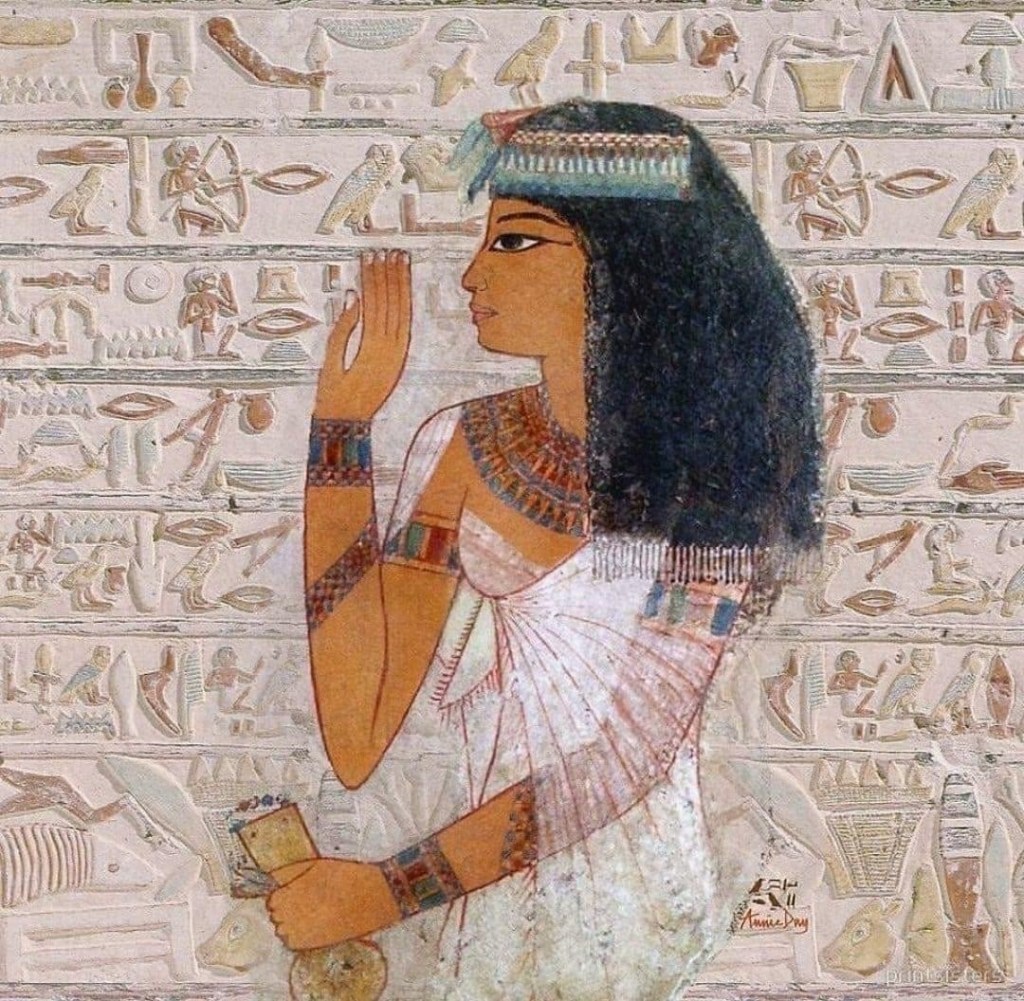

4) Meskhenet

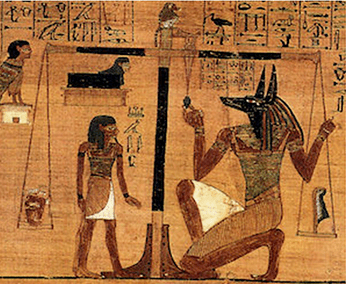

As I semi-spoiled above in talking about Heqet, Meskhenet is also a childbirth goddess, always recognizable by the cow’s uterus (Peseshkef) she wears on her head. All of the Egyptian pantheon’s many celestial cow deities (Bat, Hathor, etc) also double as divine mother figures, and the Peseshkef was meant to transfer that sacred power to pregnant people through their terms and delivery. Where Heqet’s main job was to fashion the baby within the womb and breathe life into it once it was born, Meskhenet’s role was to create a person’s ka, the very essence of their life force, and place it within a child. Because the ka defined someone’s personhood, Meskhenet was often shown as the consort of Shai, the god of fate.

[The ka of Ani weighed by Anubis (R) and Shai (L), with Meskhenet hovering above her husband’s head]

But what makes Meskhenet perhaps best qualify as an unusual goddess is the other form that she takes, particularly in funerary texts, which to the uninitiated looks like a black box with a woman’s head (see above). But this isn’t a box, it’s a brick—specifically a birthing brick. In ancient Egypt, as with many traditional cultures, women typically gave birth in a squatting position, and in Egypt, they did this balancing on bricks while being supported by a midwife and/or relatives. Meskhenet was the guardian goddess of these bricks and through them, eased a woman’s labor. She’s shown in Brick Mode in funerary texts because the dead are appealing to her to aid their kas, of whom she is arguably the mother of, through the “labor” of weighing and into their rebirth in the West. Just as Heqet is with a person before they are born and sees them through their first birth, she symbolically hands them off to Meskhenet, who sees them not only through their first birth, but all the way through death into resurrection.

3) Rekhyt

Rekhyt is a deity with a history so convoluted that for the first half of its existence, it was the exact opposite of a god. Rekhyt (rhyt)—the Egyptian word for the Northern lapwing (Vanellus vanellus)—was originally their nickname for a tribal people in the northern Nile Delta during the earliest dynastic periods, who wouldn’t be considered Egyptians until at least the third millennium BCE. As the Egyptians moved into the Old and Middle Kingdoms, “Rekhyt” became a catch-all term for peasants, or any lowly people thought to embody the clumsy, plaintive nature of the lapwing. Even in the New Kingdom, pharaohs like Seti I below were sometimes depicted with lapwings in their fists to show their control over the populous.

[Seti with Rekhyt in hand]

But as Egyptian funerary practices and Duat-lore evolved, the humble Rekhyt began to be an iteration of the ba-bird, the winged soul resurrected in the West. This was probably in part because the Northern lapwing is a migratory bird in Egypt, and its departure and arrival in the Delta was a simulation of the soul’s coveted ability to come and go forth at will from the underworld. Rekhyt the deity became the representative of all blessed souls, a son of Amun-Ra and younger brother of Horus with delightfully odd human arms sprouting from his lapwing body raised in adoration of Ra and the dead pharaohs as incarnations of the sun gods. While Rekhyt would remain a deity connected to the common people, sometimes kings would depict themselves as Rekhyt to show humility to their divine father(s). The divinity of Rekhyt is the triumph of universal salvation in the Egyptian religion over an afterlife originally reserved only for the royal family.

[Ramses III as Rekhyt]

2) Kebehwet

Kebehwet is an obscure goddess, but she just might be the most Egyptian god of them all. Because really, what other pantheon would have a goddess of embalming fluid? But that was Kebehwet’s raison d’être, and considering again how important proper burial ritual was to the Egyptian people, it’s hard to call her a minor deity. Though it adds a potentially macabre twist to the meaning of her name (“cooling waters”).

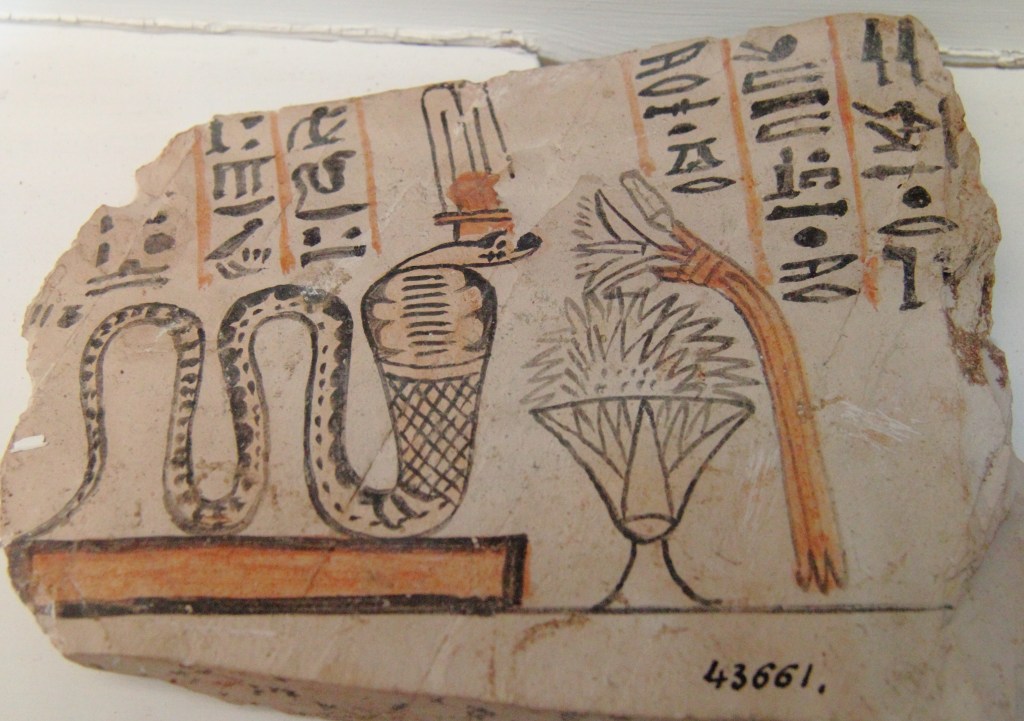

As you might expect, Kebehwet is an underworld goddess, the daughter of Anubis and his consort, Anput. Though despite having two jackal gods for parents, Kebehwet is, as you can see above, a snake deity. But like several other Egyptian serpentine gods, Kebehwet can also traverse the space between the underworld and the heavens, and according to the Pyramid Texts, can “open the windows of the sky” to the souls she purifies with holy water (unclear if that’s the embalming fluid). Some interpret these passages as meaning that Kebehwet has water that she offers to the deceased during the mummification process to keep the ka refreshed until it can be fully reborn. But as you might imagine with a goddess with such a hyper-specific skill set, she didn’t have any real cult presence outside of the isolated funerary clans in charge of embalming.

1) Nehebkau

We’re going to wrap up with one more snake god, but like the ultra meme-ified Medjed, you may have stumbled across Nehebkau before. Because he’s the snake with feet.

Nehebkau is the oldest of Egypt’s many, many snake deities, a primordial god who once was an evil serpent like Apep, but over the millennia became the protector of Ra in the heavens and the guardian of Ma’at and Osiris in the Halls of the Dead. Called “the great serpent, multitudinous of coils” in the Pyramid Texts, the Coffin Texts are the ones that claim the change in his nature was effected by Ra’s underworld form, Atum, who supposedly placed his fingernail on Nehebkau’s spine and calmed his ferocity.

Unlike Kebehwet, Nehebkau seems to have enjoyed significant popular veneration, particularly as a protector against venomous snakes, much as his sometimes-mother Serket/Selket was thought to guard against scorpions. Nehebkau’s immunity to other snakes was allegedly because he once swallowed seven cobras and that gave him heka over not only the magic of others, but also made him immune to fire and water.

While Nehebkau’s origins are varied, he is often depicted as the child of the earth god Geb and the harvest goddess Renenutet (also a snake). Because of this connection with earth and agriculture, he is seen as a nourisher of souls in the afterlife, which is when he seems to sprout arms as well as feet, as he does in the tile relief and the Ptolemaic amulet above, presumably the better to serve. But Nehebkau is also possibly the only god on this list who was major enough to have his own festival, which we know that he had, though its timing seems to have changed through the different eras of Egyptian history. Some of this is due to whether he was being honored as a harvest-guarding deity (like after first ploughing or right before winter), or as a royal guardian (as for coronation celebrations). He might often look a little goofy in drawings, but he was a powerful, respected god who survived every twist of belief in ancient Egypt. Feet included.

[Pants optional]

Leave a comment