“I spent nearly five years at the knees of the Poitevine princesses, my lord. They taught me to trust a Turk before a Lusignan.” – The Gourd and the Stars, chapter fourteen

Much like with the world of The God’s Wife, there’s a lot of ancillary tangents to explore in the medieval Mediterranean of The Gourd and the Stars, and this week I wanted to take a look at perhaps one of the period’s most unexpected royal houses—that of the House of Lusignan. Beginning as petty French lords with claims to a monstrous mythic heritage, the Lusignans would find themselves over the course of less than a century raised from noble quasi-brigands to kings in two eastern monarchies through strategic cunning and plain dumb luck. So I thought we’d see how they got there.

We don’t know much about the Lusignans before the late 9th century CE, which is when their primogenitor, Hugh I (?885-930 CE), was given the vassal lordship of Lusignan, a town/area near the county seat at Poitiers of their overlord, the count of Poitou. Throughout their subsequent aristocratic history, the Lusignans would love epithets—in part because the name Hugh would become the standard given name of every firstborn son and it rapidly became necessary to try to differentiate everyone—and it is through Hugh I’s, Le Venator (Le Veneur in his native Occitan dialect), that is, The Hunter, that historians have hypothesized he originally held the office of huntsman for either the count of Poitou or the bishop of Poitiers, who owned the forest bordering the new lord’s eastern lands.

Hugh I’s son, Hugh II (strap in, it’s going to be like this), nicknamed Le Carus (The Kind), is credited with one of the dynasty’s earliest notable accomplishments, which is the construction of its impressive stronghold, the Château de Lusignan, on a promontory overlooking two opposing regional valleys. Although the castle wouldn’t reach its full size and magnificence until the early 14th century (see the illumination from Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry below), within a century or so of its initial construction, it was already enough of an engineering achievement that the Lusignans were thought to have received supernatural aid building it. And this is where the monster legend begins.

As we discussed in my post about the Middle English poem, Richard Coer de Lyon, medieval aristocratic houses claiming mythical ancestors, even ones of monstrous or demonic origin, were commonplace, particularly in the early/High Middle Ages. The mythological ancestor was more often than not the mother, which allowed the descendant lord to hold both the benefits of a genetically secure descent from a normal, noble male line as well as potential supernatural abilities/luck derived from an uncanny female line. This may have also been a trope holdover from the Aeneid, where the hero is the son of the mortal Anchises and the goddess Venus; a story medieval European aristocrats would have been familiar with.

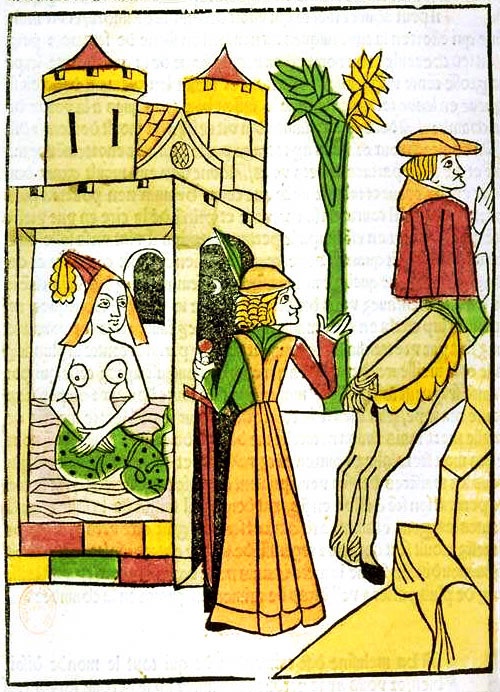

When talking about Richard I of England’s demonic mother, Cassodorien, in the poem, I had placed her in a well-established European folklore tradition usually referred to as The Demon Wife/Bride. In this milieu of stories, a nobleman or a king marries a beautiful, mysterious woman who typically hinges her consent to the union on a demand such as her husband can never look at her at night, or while she bathes—a motif that probably has some descent from Greek mythology (cf. the Cupid/Pschye myth, itself the likely western origin of the gender inverse tradition of The Demon Husband, and the Artemis/Actaeon myth). The husband, transfixed by her beauty, agrees to whatever she demands, and usually the couple lives happily for a while, long enough to have several children (which you need if you want this to be a foundational myth for your family). Then, at some point, either the husband’s curiosity gets the better of him (à la Psyche) or he sees her accidentally during the proscribed time (à la Actaeon), and the wife is revealed in some monstrous or mythical form. At the breaking of his promise, the wife immediately vanishes or departs, and the husband is left alone with their offspring.

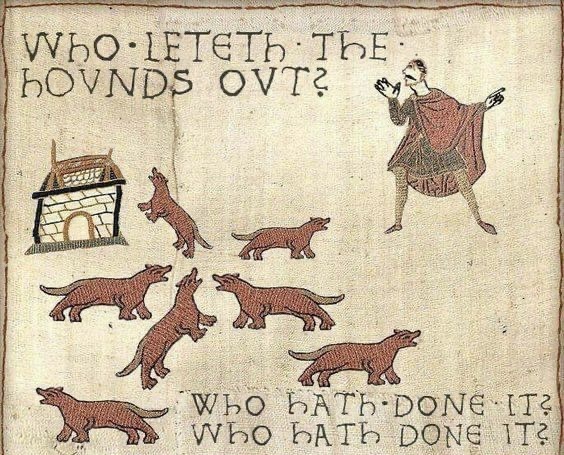

Cassodorien of Coer de Lyon is a variation on the motif—a demoness who flies away from her marriage rather than gaze upon the Eucharist—but the prototypical European Demon Wife is Mélusine. Mélusine is sometimes a fairy, but more often than not, she’s a lamia (Greek: Λάμια)—a half-serpent woman (who may or may not have wings). The water snake iteration of the Demon Wife proved to be extremely popular among medieval nobility, with several houses claiming descent from a Mélusine figure, including the French House of Anjou (and through them, the Plantagenet English kings) and Flemish/Germanic House of Limburg-Luxembourg… and the Lusignans. While the regionally-adjacent Mélusine myths initially tie her to the Lusignans’ overlord, one of the many Count Raymonds of Poitou, in southern France, Mélusine became increasingly identified with the crafty, lucky Lusignans over the centuries. To the point that residents of the modern city of Lusignan in their historic lands in Nouvelle-Aquitaine are still known by the demonym Mélusin(e)s.

Anyway, whether or not Mélusine helped Hugh II build the Château de Lusignan, after a relatively peaceful period where they were headed by his son, Hugh III Albus (The White), the Lusignans began their true familial project: being as big a pain in their neighbors’ asses as they could manage for the next several centuries. Beginning with Hugh III’s son, Hugh IV Brunus (The Brown), the Lusignans started an aggressive policy of territorial expansion against other local petty lords and clerical landholdings. Sometimes this was to the advantage of their overlord, the count of Poitou (now also the duke of Aquitaine), and sometimes it was a huge problem for them. Whether the titular head of the clan was granted a seemingly benign epithet (like Hugh V’s Le Piuex, The Pious), or one that more reflected their general “deal” (like Hugh VI’s Le Diable, The Devil(ish)), like many houses of the medieval lesser nobility, the Lusignans were in constant competition for land and wealth with both those above and below them on the hierarchical ladder.

Hugh VI’s nom de guerre came from his contentious relationship with the abbey of St. Maixent, a drawn-out dispute that not only embroiled the duke of Aquitaine and the bishops of Poitiers and Saintes in it, but almost got Hugh excommunicated by Pope Paschal II. Maybe partly because of this unholy situation with the pope, Hugh Le Diable is also the first Lusignan to go to the Holy Land, as he participated in the First Crusade in the retinues of his young stepbrothers, Raymond IV of Toulouse and Berenguer Ramon II of Barcelona. Unfortunately for him, he would be killed at the Battle of Ramla in 1102, which would end Lusignan contact with Outremer for the present, but would begin a crusading tradition in the family similar to those found in other aristocratic houses.

Incidentally, Hugh Le Diable’s mother, Almodis of La Marche (c. 1020-1071), from whom the House of Lusignan would inherit the title of counts of La Marche, is a rather fascinating figure herself. She and Hugh V would divorce, seemingly amicably, within a few years of marrying one another (though they still had three children together) based on consanguinity, and Hugh then helped her marry Pons II of Toulouse, whom she would be married to for thirteen years. Her marriage to Pons “ended” when she was abducted by Ramon Berenguer I of Barcelona and he married her… while also already married himself. Almodis seemed fine with this, and she kept in close contact with all of her families while the pope excommunicated them for this bananas bigamy scheme they had going. Almodis would eventually be murdered by her third husband’s original heir, who didn’t like her son’s horning in on his patrimony.

I know that Almodis digression seemed like a complete non sequitur, but it did bring into our discussion a common aspect of medieval life that is nigh incomprehensible to our contemporary sensibilities—the abduction model of matrimony. Through most of the Middle Ages, many of the major and lesser land titles were permitted to be passed through daughters and female relatives. But in a world where even the most competent woman would run up against contemporary gender limitations both in the law and the military field, this led to a roaring trade in heiress wardship. A lone orphan or widow still within her fertile years with a rich patrimony could trade on that patrimony to gain protection from a powerful male lord, who while technically required to safeguard her fortune, could in practice leverage those resources for his own use and gain from the heiress’s (re)marriage, either to him, a family member, or a vassal. In its most legal, organized iteration, a monarch or overlord would assign control of a dependent heiress to a lord—this is essentially how William Marshal became the earl of Pembroke—but again, in practice, as we saw with Almodis, possession of an heiress (or a wife) was nine tenths of the law, so there was a huge incentive for anyone to just kidnap the heiress and hold onto her.

And as we move with them into the 12th century, the Lusignans become big gamblers in this arena, in part because the house of their liege lord, the extremely rich and powerful dukes of Aquitaine, found themselves in this exact heiress quandary when William X of Aquitaine dies with only eldest daughter Eleanor to inherit his lands and title. By then, the Lusignans were the most powerful of Aquitaine’s vassal lords, and while Hugh VII (another The Brown) was ostensibly loyal to William X, part of the reason Louis VI of France moved in so swiftly to marry his son to Eleanor was because of a real threat of families like the Lusignans riding off with the young duchess before her father’s corpse was cold. Hugh VII must have reconciled himself to the overlordship of Eleanor’s new husband, Louis VII, because he joined the royal couple on their ignoble crusade in 1147, and while unlike his devilish father, he managed to survive the ordeal, he was dead within a year of his return. Which led to the ascension to the title of his son Hugh VIII, nicknamed Le Vieux (The Old), and this is where all hell really breaks loose.

Some of the turbulence in the House of Lusignan that began in Hugh Le Vieux’s times is due to the nature of the relations between their liege lady Eleanor and her two husbands, Louis VII of France and Henry II of England, where allegiances were in constant flux and the Lusignans were willing to test boundaries to see what they could get away with (including trying to kidnap Eleanor when she was between marriages). The rest was because even by the standards of the Lusignans, who had never been at a loss for heirs, by the time Hugh Le Vieux was lord of the family in 1151, there were so many of them. Hugh’s only wife, Bourgogne of Rancon, had seven children—all boys—only one of whom died in childhood. That left six young men with little to do but stir up trouble whenever it suited them. This only intensified when Hugh Le Vieux went on pilgrimage to Palestine in 1163 and was promptly taken prisoner by Nur al-Din’s Syrian forces in the disastrous Battle of Harim, where Muslim forces crushed the crusader armies of King Amalric of Jerusalem and effectively ended all Latin territorial expansion in the east. He died in captivity shortly after.

Hugh Le Vieux’s death brought his eldest son, Hugh (obviously), to the lordship, but Hugh was dead so quickly (~5 years later) that he’s not even usually given a number in Lusignan ordering. Hugh No Number left two toddler sons, one of whom would eventually become Hugh IX (yet another Le Brun), but during his minority, control of family affairs would be assumed by Hugh’s eldest surviving younger brother, Geoffrey de Lusignan. Geoffrey, probably himself still in his mid-twenties, would promptly rope his younger brothers into forming a posse of ne’er do wells who ran rampant in southern France, joining any local rebellion that might give Louis VII or Henry II a few headaches. Youngest Guillaume was barely any older than Hugh No Number’s boys and escaped the worse of it, but Pierre, Aimery, and Guy spent most of their teen years either fighting alongside Henry of England (the Young King) against his father, or rebelling against Prince Richard, who was their liege lord in Aquitaine. Henry II finally stamped out this insurrection, but Geoffrey would be playing with fewer brothers in crime when it was over. Henry chose to let Geoffrey’s sins as instigator slide, as well as those of the very young Guy, but Pierre was packed off into a priesthood and it was strongly suggested that Aimery develop a sudden interest in a pilgrimage to Jerusalem.

But it’s this shift away from the interminable line of Lusignan Hughes that will ultimately change the destiny of the family. Aimery was in his early twenties by the time he showed up in Latin Palestine, and while being the renegade fifth son of a minor French noble sounds like an inauspicious starting place, he wasn’t without resources. Even if his father’s sacrifice for the kingdom’s cause had been overlooked by King Amalric (and it wasn’t), Aimery seems to have been able to make himself well thought-of in very short order. While we don’t have a lot of contemporary comment on Aimery’s personality, we do know that he quickly gained an ally in the king, as well as Agnes of Courtenay, both when she was queen and after her divorce from Amalric. Additionally, while rumors swirled that he was romantically involved with Agnes, Aimery still made a strategically advantageous alliance with the powerful Ibelin clan by marrying Baldwin of Ibelin’s daughter, Eschiva. All of this points to a man who was clever enough to try to balance himself between the various Jerusalem factions, while being personable and competent enough to do it successfully. These are traits he shared with both King Amalric and his son, Baldwin IV, and they recognized this by having Aimery serve first as Lord Chamberlain (head of the royal household) and later as Lord Constable (head of the army) of the realm, two of the four highest offices in the kingdom. And he did all of this in barely a decade.

Seeing that Aimery had done so well for himself abroad, it’s little wonder that his older brother Geoffrey back in France might consider strengthening the family hegemony in Outremer. We don’t know exactly when Guy was sent to join Aimery in Jerusalem, but it was presumably after Aimery was well established at court. Scholars put the likely range between 1173-1180, while I personally favor 1179, seeing that was the year a significant contingent of the French nobility, led by Henry I of Champagne went on pilgrimage to the Holy Land and it seems natural that Geoffrey would send Guy as the family representative. We also don’t hear about any especial exploits of Guy in Palestine any earlier than that, which seems odd if he was already there. But this is where all of Aimery’s excellent groundwork with the Jerusalem nobility paid off because in 1180, a disagreement about the remarriage of Sibylla of Jerusalem, Baldwin IV’s sister and heir, nearly sparked a rebellion among Baldwin’s vassal lords, and led to the surprise emergence of Guy as the one candidate nobody hated enough to go to war over. So on Easter Sunday 1180, Guy married Sibylla, and with an “I do,” the Lusignans found themselves next in line to the throne of Jerusalem.

Now, a lot of ink has been spilled about Guy’s personality because ultimately it’ll be him holding the reins when Salah al-Din brings the whole kingdom of Jerusalem crashing down in 1187. And it must be acknowledged that Ridley Scott proves he makes a delicious villain. Certainly we know that, unlike the apparently popular Aimery, Guy never really “made it” with the Frankish barony in Jerusalem. Those who didn’t think he was stupid or actively evil seemed to have found him haughty and abrasive. Some of that was surely envy at the luck that found him eventually king-consort—especially given that, forced at one point to divorce him, Sibylla chose him again later—but Sibylla really appears to be the only one who liked him that much. In the end, when I was trying to flesh him out as a character for Gourd, I found myself comparing him to Tsar Nicholas II of Russia: not an evil man, but one wildly unprepared by ability or temperament to meet the hinge historical moment he found himself in. He was by all accounts a brave enough and competent enough knight, but he seems to have been a spectacularly bad leader of men in a monarchy that lived and died by an individual king’s personal charisma and ability to unite disparate interests. Much of what we know about Guy has been written by his enemies, but his failures point to a man who is at least some of the things alleged of him.

Guy also just didn’t have Aimery’s luck. When Sibylla and their daughters died during the Siege of Acre (1190), Guy wasn’t popular enough to hold onto the throne in his own right, and he would have to spend most of the Third Crusade trying to get anyone to support him staying in power besides his loyal brother. He got Richard I on his side, but that’s probably because Richard, still duke of Aquitaine as well as king of England, saw use in having one of his vassal Lusignans on the throne of Jerusalem. But it is a testament to Guy’s aggressive unpopularity that even the charismatic Richard couldn’t win this argument for him, and Guy was deposed in favor of Conrad of Montferrat and Sibylla’s half-sister Isabella in 1192. Richard gives Guy a consolation lordship over the island of Cyprus, which the king of England conquered on a whim on his way to the crusade—which Guy still has to buy off the Templars to take ownership of. But he does it and rules over Cyprus before dying two years later in 1194. Without surviving children to pass the title to, Guy’s few remaining vassals elect Aimery as their new lord, and within a few years, Aimery has officially instated rule of Cyprus as a monarchy and is king of the island.

Aimery rules Cyprus for a couple of years until Isabella of Jerusalem’s latest husband Henry II of Champagne died—I kid you not—falling from a window (Conrad got taken out by the Assassins five years earlier), leaving the oft-married queen a widow again at barely twenty-five. The Jerusalem barony looked around and decided, perhaps against all odds, that the best consensus candidate for king-consort was the also recently widowed Aimery; another testament to his enduring popularity in the Frankish east. Aimery married his dead wife’s cousin and was crowned king of Jerusalem thirty years after his arrival in the Holy Land. He would rule both Jerusalem and Cyprus for another seven years before dying in 1205 of—again, not kidding—“an excess of white mullet.”

While the throne of Jerusalem would stay with Isabella and eventually pass through her daughter with Conrad of Montferrat, the kingdom of Cyprus would remain in the Lusignan line through Aimery’s son and his heirs until the island was annexed by the republic of Venice in the 15th century. This combined with the Lusignans’ continued influence in Continental affairs in France and England made them for most of the remaining Middle Ages a truly global powerhouse. Not too bad for the kids of a huntsman and a water snake🐍

Leave a comment