This week, I thought we’d get back into some writing mechanics content and talk more about the process of constructing a story that is satisfying to write as well as read. A debate that gets a lot of airtime in creative circles is whether it is better to plan out every aspect of a story, or write everything on the fly and let it take you wherever it ends up wanting to go. I think what gets many people hung up on starting (or finishing) a creative endeavor is hyper-focusing on either of these approaches. Like so much of things in life, I think a middle path is perhaps the most helpful to the largest number of people—that you need some kind of idea of where you want to go in a story, but you have to move with a certain degree of flexibility, too. Sometimes, even in a genre like historical fiction where one is at least somewhat bound by factual events, your story or your characters will go in a direction that you didn’t initially plan for, and part of growing in the writing process is learning to judge if and when to either rein this in or let it happen. As my title suggests, I generally find the latter approach to yield the most organic results, but I thought we’d (messily) explore the process through some examples from my books so you can see this in action.

What got me specifically thinking about this was one of what I’d call my “intrusive characters,” that is, a character I originally intended to have a certain role in a story, who seemingly of their own volition manages to work their way into a larger/different role in my plot. I know it can seem like downright witchcraft to civilians when writers talk about how a character “just hijacked!” their story, but it’s happened enough to me that I can attest to it being a real thing. If I had to try to explain this phenomenon, though, I would postulate that it comes from two places: one, when I’m in the middle of writing a manuscript, I’m low-grade always turning the story over in my mind and this constant rock tumbler is prone to spitting out almost every iteration of your plot. So when the new “cream” rises to the top, it sometimes feels like it’s coming from the ether outside your own imagination. Secondly, if you’re not wedded to a very rigid version of your plot, as you write out what you think you want to, sometimes the logic of what you’re writing changes as you go. I know that this is a jumbled explanation, but I think I can explain it best with specific examples which will show how this works so you can see that, as serendipitous as it sometimes feels, it isn’t magic and anyone can learn to do it. Because, as always, I want to demystify the writing process for anyone who wants to dip their toes in but is intimidated by the way we writers sometimes talk about writing.

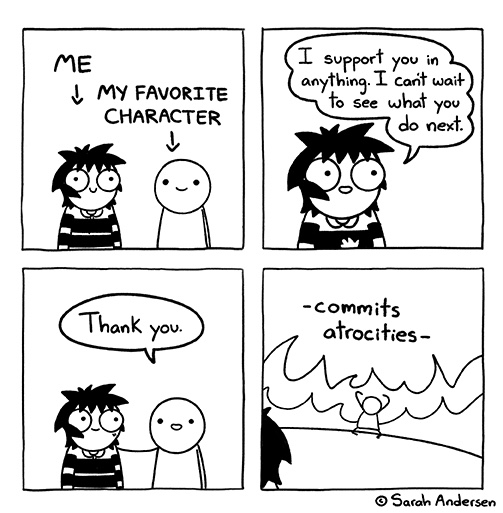

The first intrusive character type is probably the one that feels like the purest product of imagination, where the character really does seem to have a mind of their own. In my books, the archetypal example of this is Ovid (Ovidius) from my God’s Wife series, especially in Daughter of Eagles. I initially intended for Ovid to be little more than a supporting character in my story, simply a comic foil for Horace (Horatius) and a contrast to Virgil (Vergilius). But by the time I had Aetia rolling into Baiae on Marcellus’ tail in Chapter 31, Ovid was threatening to hijack her entire romantic subplot and possibly the plot proper. As the book that required the most rewriting/restructuring on my part past the first final manuscript, my notes are full of angry exclamations at Ovid for elbowing his way toward my OC without permission and remarks from my editor that their chemistry was more compelling than the relationship I was building between Aetia and Virgil (something my readers might agree with).

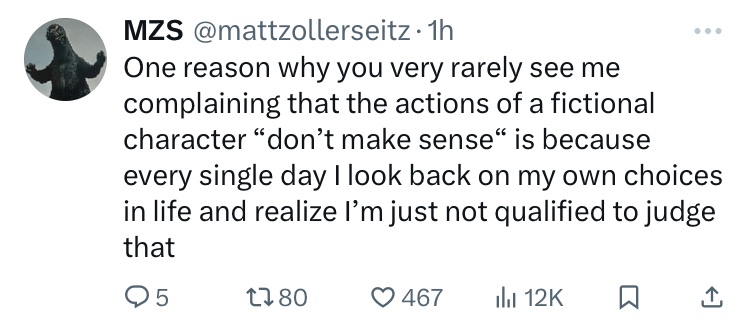

But how did this happen? As much as it all felt in the moment like it was happening against my will, “living” characters like Ovid are mostly the result of solid creative groundwork. Like any historical character with a significant role in my books, my Ovid was the product of the kind of research process that we discussed in my entry about Baldwin IV. We don’t actually have much biographical information about Ovid outside of what he writes about himself in his poems, and while he’d spend most of his exile in Tomis swearing up and down that is an (almost) entirely fictional version of him, the conclusion I reached after studying the crumbs of his life is that there is definitely more than a grain of truth in his self-portrait. So the Ovidius of my books is an irreverent rogue in the vein of his poetic personal, but with a sincere streak large enough to explain why he was drawn to love elegy rather than more “important” styles of poetry and why he scorned a lucrative public career as a rhetorician. This strong characterization lets a character move through your plot in a way that feels organic and they will then start to help you make decisions about how to use them.

Once a character starts behaving this way, you have two options: you can let them change your plans, or you can try to direct them. Ovid’s case is an example of the latter; as great (and fun) as he and Aetia were together, he was not what I wanted for her character growth in Daughter of Eagles. My God’s Wife books are in part about the longing for balance in a chaotic world, and matching Aetia with someone who was similar to her in personality wouldn’t help her meet a destiny that would require her to be prudent as well as brave and clever. At its core, story-wise, the Aetia/Ovidius ship is fun, but they both needed to grow up first. So, my creative compromise to the character I had created was not a complete refusal, but delayed gratification. Children of Actium becomes the Aetia/Ovidius ship story, because I do agree they are fun together, but also because we get see them together both in that book’s present and in flashback to a time between DoE and CoA, we let them have a full relationship and not just a sexy fling (not that that can’t be fun, too).

A second intrusive character type, at least in the genre I’m writing in, is one born of the historical record against your original intentions. The best example in my books of this is the character that got me thinking about all of this in the first place: Gourd and the Stars’ William Marshal (Guillaume le Maréchal). Although some of what we know about William is hype from the history of his life commissioned posthumously by his children, even at its most stripped down, the Marshal was a remarkable figure in his time. As a second son of the lower nobility who rose to fame and an earldom on the back of his skills on the 12th century knightly tournament circuit and his actual military acumen, he was a literal embodiment of the medieval literary ideal of the courageous knight errant.

For all the potential biases of The History of William Marshal, it was still a valuable primary source for creating my Maréchal for my story, especially since I merely meant for him to serve as a foil to his master, the handsome and arrogant Harry the Young King, so my Zénaïde could have two versions of knighthood to compare. I initially intended the Maréchal to have his time in the Paris part of Zénaïde’s journey, and then he’d stay behind with everyone else when she left for Palestine. But as I was reading both the History and one of the many secondary biographies of Marshal (Thomas Asbridge’s The Greatest Knight), I realized that William made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land during one of the pivotal moments in my plot (1183-1186). Not only that, the usually effusive History is weirdly evasive about what William got up to in Jerusalem—no knightly exploits, no derring-do, nothing besides some contact with the Templars.

This lacuna is even more glaring when you account for the fact that it is obvious that most of the material for the History clearly comes directly from reminisces shared by William to his children, so this dearth of information on this period means that he didn’t want to talk about it for some reason. Perhaps William simply didn’t want to dwell on being in the Holy Land during the unsettled time around Baldwin’s death and the rise of Guy de Lusignan, a person and family the Marshal had (negative) history with, all of which he had little influence or control over. Maybe in a hagiography celebrating his knightly achievements, he didn’t want to draw attention to his lack of prowess in defending Christendom and the fact that he left the East right before Jerusalem fell to the armies of Salah al-Din. But as I’ve said before, historical gaps are my creative catnip, and I realized that I couldn’t ignore William’s presence at this cataclysmic point in my story. So, I revised my original ideas and brought the Maréchal over to where he was supposed to be so he could be a friend to Zénaïde at a moment where her whole world is crumbling and she is in desperate need of a perfect knight to defend her honor. And someone capable of protecting her secrets—even if that casts his pilgrimage in a less classically heroic light.

We’ve looked at two versions of intrusive characters that are at least partially products of the natural creative process, but to finish up, I want to illustrate perhaps the least organic type, which let us call “the solution in search of a problem.” Because even though, judging by the laments I read on Twitter, I don’t usually find the writing production process as tortuous as some do, speed bumps do crop up and I want to show some of the warts to you all so you don’t think everything jumps out of my head fully-formed like Athena. To do this, we’re going to turn back to Daughter of Eagles.

To be upfront with you, DoE is the only manuscript that my editor has ever returned to me with the (gentle) suggestion that it needed more refining before I published it. Obviously, stuff like that still stings, but she was 100% right. One of her major critiques was a lack of overt conflict in the original manuscript outside of the vague machinations of destiny and the shadowy coup plot. Some of that was fixed by writing in more narrative breadcrumbs around the coup and the characters involved, but I knew that wouldn’t fix everything. So, I went search of more overt conflicts for Aetia to have outside of her shadowboxing with Octavius.

That’s when Octavius’ daughter Julia stepped into the forefront. I had initially shied away from conflict between Aetia and Julia because one of my side goals for the story was to buck ancient opinion on Julia as frivolous and spoiled, mostly because I think she was a girl in an impossible situation where the rules were being made up underneath her and that contemporary men did her dirty. But as I reevaluated my story, I realized that by forcing them to get along, I was actually preventing my defense of Julia from unfolding naturally, and Aetia could be an effective conduit for my readers to discover the “real” Julia alongside my OC. So I basically went in and rewrote all of their story prior to the post-funeral scene to be one where Aetia finds Julia rather frivolous and spoiled at the beginning and Julia is jealous of her father’s attention to Aetia, but they learn through circumstance that they aren’t so different and become friends. This had the added benefit of giving Julia more depth as a character and not just being a third person in her narrative troika with the Antonias. But as you see, Julia didn’t suggest herself to me until very late in the creative process, and while her arrival wasn’t as spontaneous as Ovid’s, it was ultimately just as timely.

So, yeah, that’s some insight into how your story can evolve through your characters as you write it, even when you’re in a more restrictive genre like historical fiction. As I tried to distill it for my wife, part of having those moments where it feels like your characters are moving around on their own is understanding that they have legs because you, the writer, gave them those legs, and the trick is learning how to give them legs—which I hope I’ve shown you is often just a matter of laying good foundations as it is the more intellectually sexy flashes of inspiration. For me, it’s usually the result of a lot of research, but it can also be from doing things like making stat pages about your characters to track appearance, personality, etc, if that’s more useful to you. Understanding your characters gives them the momentum to move your story—both in your intended direction and sometimes against it—and it’s that give and take that can produce some really extraordinary results, so don’t be afraid to embrace it!

Leave a comment