We’re hopping back into some museum content this week because last night I had the opportunity to attend a members event at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History for their new temporary Egyptian exhibit, The Stories We Keep: Conserving Objects from Ancient Egypt meant to fill the gap during the Walton Hall of Ancient Egypt’s long renovation closure. We’ve seen previously how the museum has been using small pop-up exhibits outside the hall on the third floor to try to keep people engaged while one of the most popular parts of the museum is under construction, but The Stories We Keep is the first to be a full-scale exhibition.

As you can guess from the full title, The Stories We Keep is using the Egyptian hall’s renovation as an opportunity to begin to reframe an old, problematic collection away from gaping at mummies prurience toward something more befitting a contemporary scientific institution. The final form of the new Walton Hall is, as I’ve intimated before, I believe going to be a focus on Nile Delta ecology, but this interim exhibit is using the disorder of the renovation to talk about museum conservation with the general public, which is just a fabulous idea, in my opinion. Conservation work often goes unnoticed and unsung in all sorts of museums, and this is the perfect excuse to not only demonstrate the science behind keeping objects as old as those from ancient Egypt, but allow critical members of the museum staff to have a moment in the sun. The exhibition has been open for a couple of weeks now, but the members event gave me a chance to do one of my favorite activities—museum after hours—so I jumped at this instead of my usual day trip. So come take an evening stroll with me and let’s see what the conservation team has cooked up for us!

Just off the bat—and contrary to what my Dionysian picture above might imply—I think that this exhibition does a wonderful job of being age-inclusive. It was interesting for me to learn more about artifact conservation than I already knew, but there were a lot of hands-on stations for younger folks get them involved, and I was really glad to see so many kids at this event (especially since I was afraid it was going to just be me and a bunch of old, rich people). The kiddos seemed to be jazzed by what they encountered, and I was happy to watch them running around and interacting with things. Museums live and die on youth engagement, and this is a great way to get them excited about the future of a hall that they currently know as a cramped, out-of-date room with a smattering of clay pots and ushabtis.

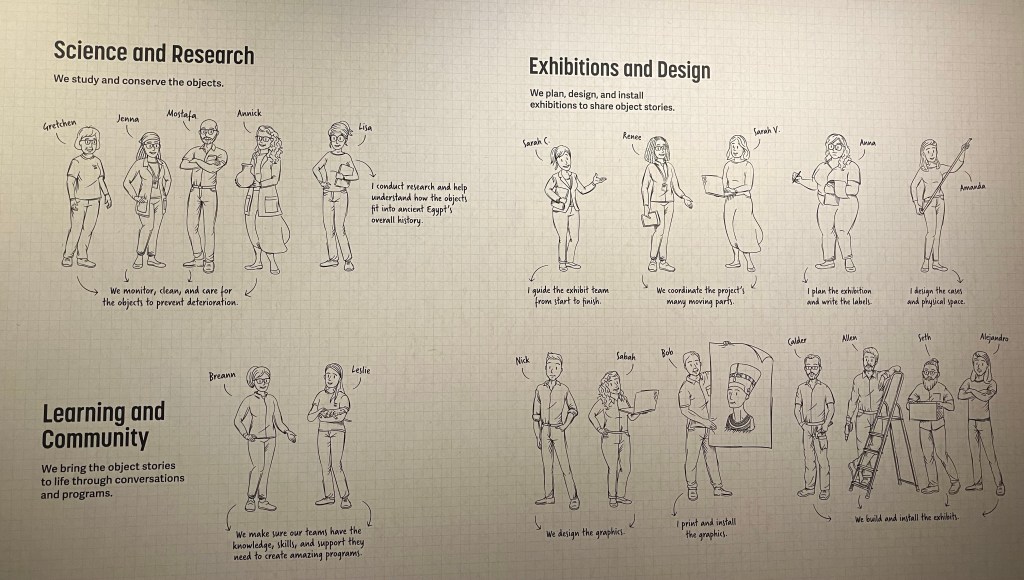

We tend to think of “conservators” as just the folks in gloves working with Q-tips, but another thing The Stories We Keep does an excellent job of explaining is all of the different kinds of specialties that are needed to build and maintain a positive environment for fragile collections like the Egyptian one. The science and research team is vital, obviously, but how often do you think about a person like Amanda (top row, far right), who designs the cases that not only make the objects optimally visible, but also keep those various objects from deteriorating in bad lighting or air contact? Or the guys in the carpentry team below her who actually have to build said cases?

Honestly, this graphic was great because, having taken a picture of it near the beginning of the evening, I could look at both photographs of the team working and recognize people (“Oh, that’s Mostafa helping to take that stela out of its case…”), and also be able to better triangulate what they might be specifically doing (“Oh, Sabah’s drawing says this is Renee—she’s one of the project coordinators, so she’s probably trying to help the researchers decide if this is an object they should be preparing for display or storage…”).

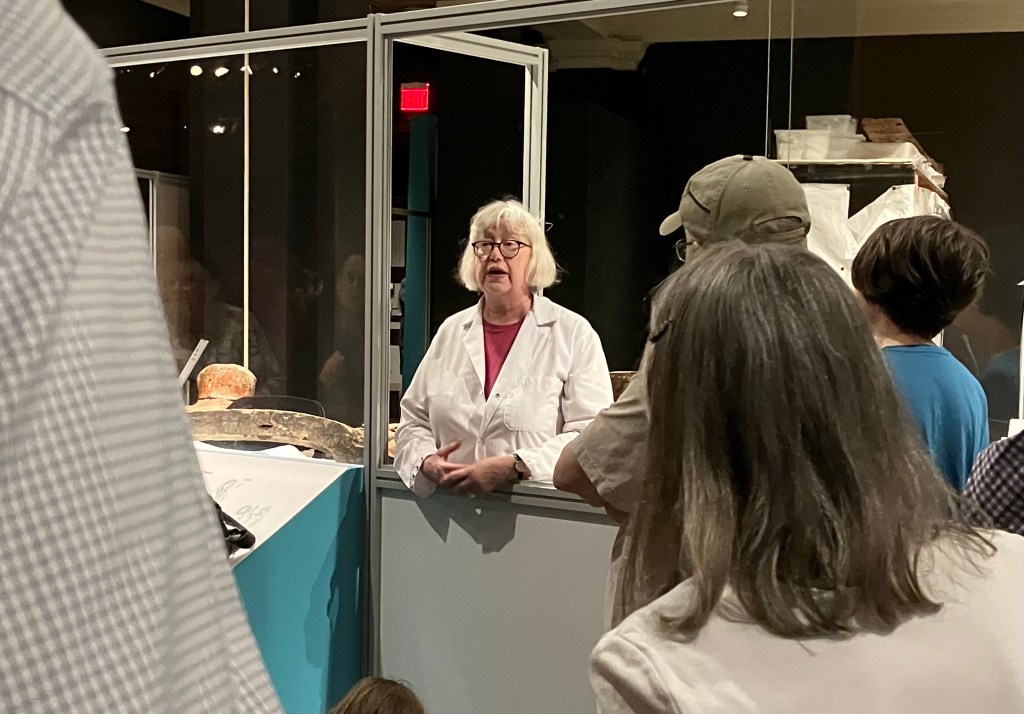

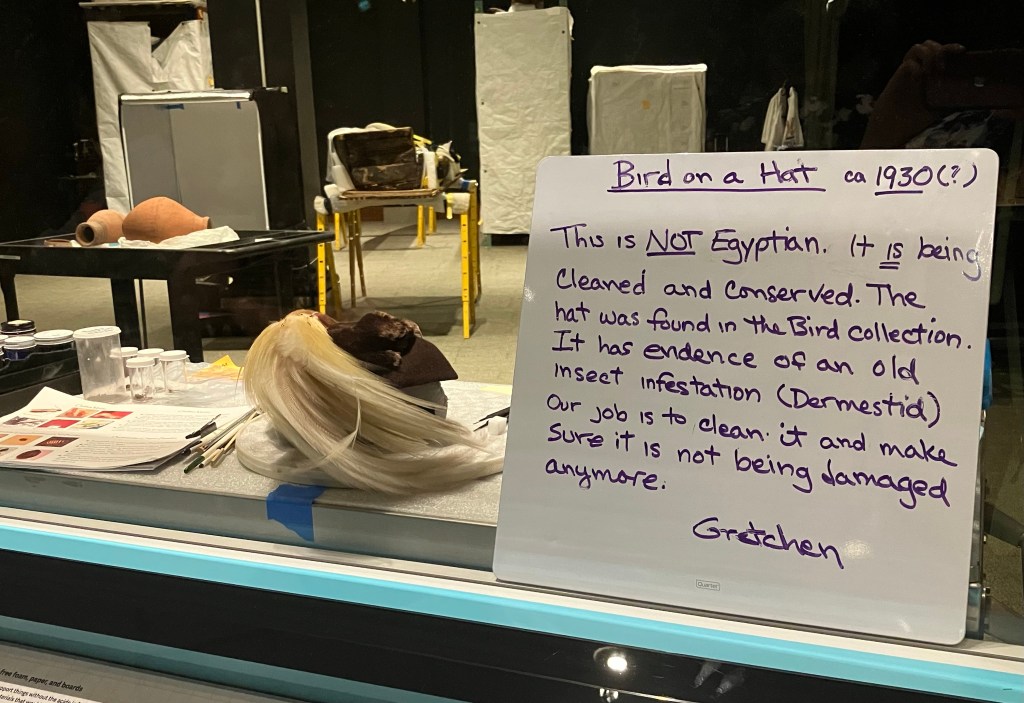

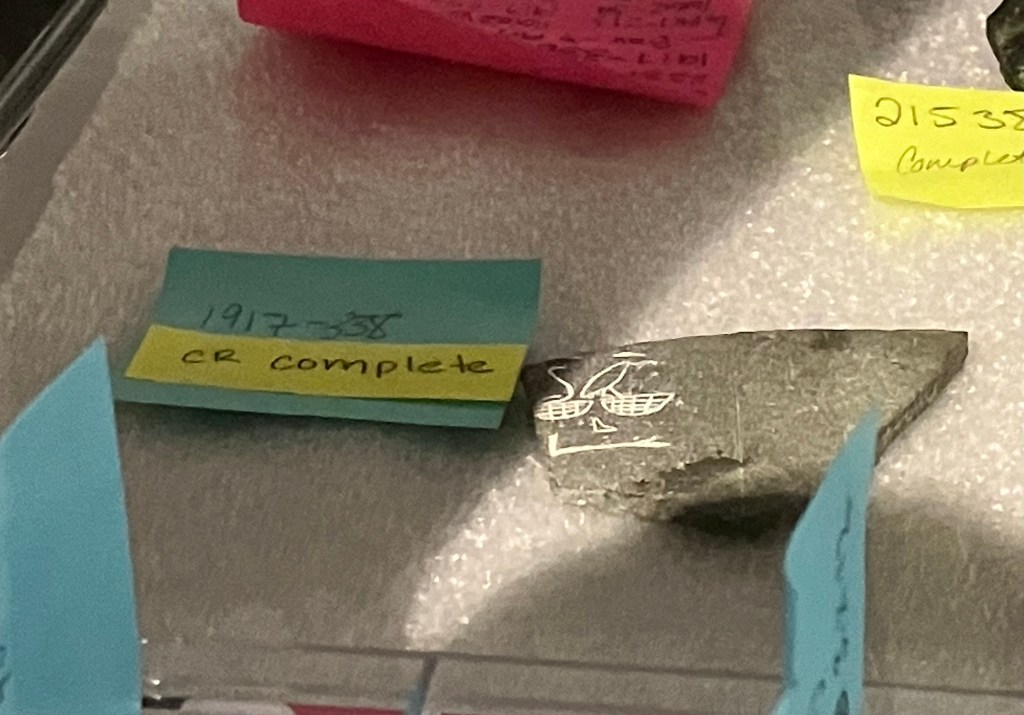

Oh, yeah, that’s the main attraction of The Stories We Keep—some of the conservation work is happening in situ in the exhibition. An entire section of the exhibition hall has been set up as a lab for conservators, much in the way that museum patrons have for years been able to watch researchers work in the paleontology lab on the first floor. Like with the paleontologists, this is truly their workspace, but they are setting aside a few time slots during museum hours to allow guests to interact with the conservators and ask questions. Because of opportunities like this, obviously some of the reason for doing things this way is purely public relations, but the large exhibit lab also serves a functional purpose for the science team—because it might be the easiest way to have the space necessary to work on Walton Hall’s largest occupant.

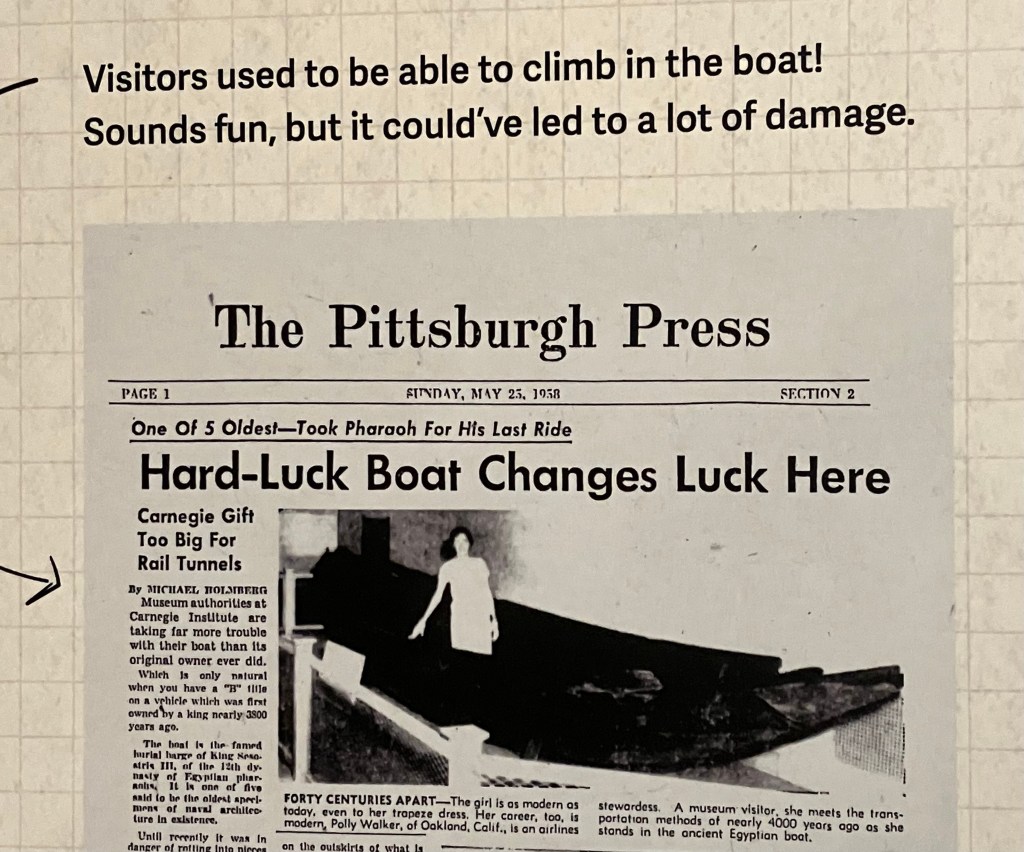

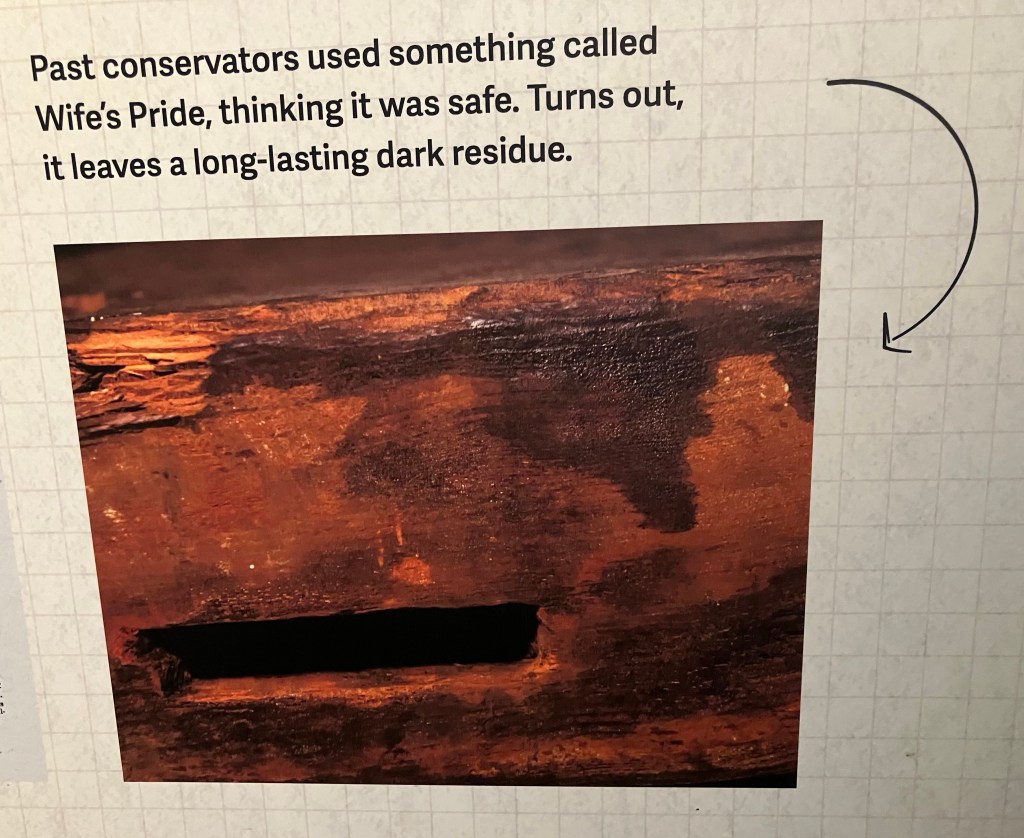

As I talked about several years ago now, the first time I introduced many of you to this collection, the star artifact of CMNH’s otherwise modest Egyptian acquisitions is one of the funerary barques belonging to Senwosret III (1878–1839 BCE), or one of his wives. One of only a handful of surviving vessels of this type, the barque is therefore a potential wealth of information about funerary practices and ship construction during this part of the Middle Kingdom, even if the boat was not built to be river-worthy. But because of its size and delicacy, the barque of Senwosret has always been a conservation nightmare for the museum staff. In the graphic above, the museum historians talk about how the field of conservation is less than a hundred years old, and therefore there were many years between the barque’s acquisition in 1901 and serious attempts at its preservation by the museum. Because the barque was too big to fit through the doors upon its arrival (and even if they’d gotten it into the building, there was no space inside for it), the boat lived in an outdoor wooden shed for five years until an addition could be built for it, exposing the ancient wood to humidity and pests. And even once it was finally in the museum, for decades it was displayed out in the open, where museum visitors were encouraged to touch it and even climb into it.

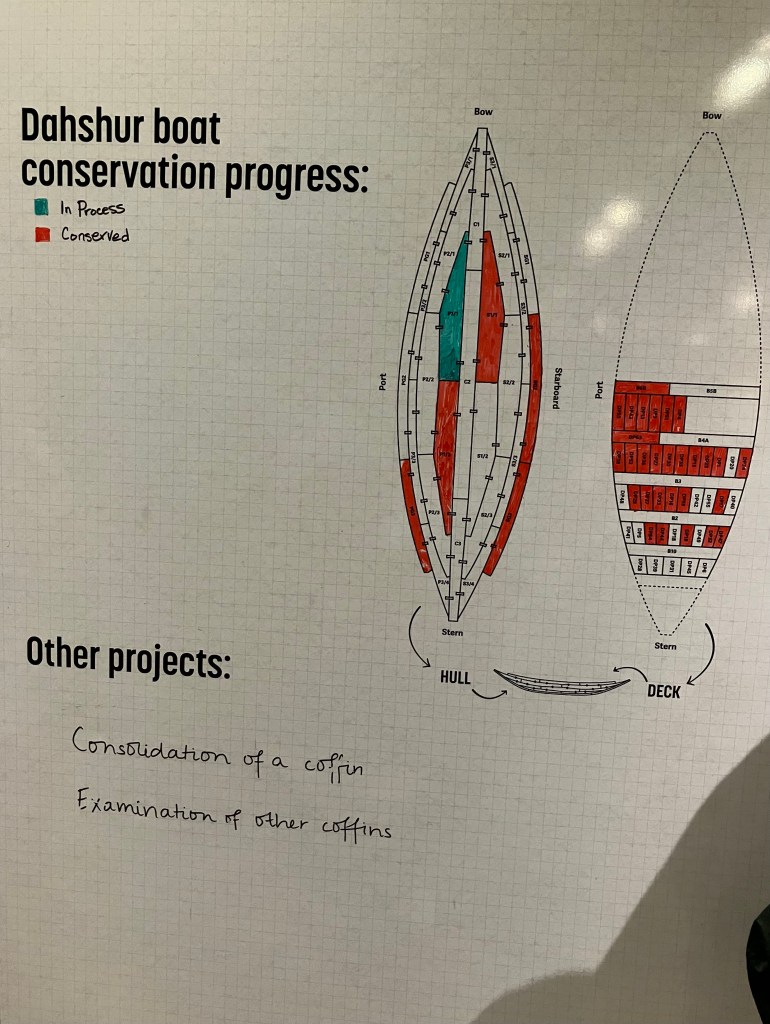

Anyway, in contemporary times, I’ve never seen the barque outside of its hermetically sealed glass coffin off to one side in Walton Hall, where it lies like Snow White waiting for her prince. But Walton Hall has barely been big enough to house it, so I’m sure part of the hall renovation is aimed at moving the barque to a more appropriate position and making it the centerpiece of the new space. In the meantime, the conservators are keeping the disassembled pieces of the barque in temperature-controlled spaces and working on them individually in blackout tents to clean and restore them for the future exhibit (and presumably trying to figure out wtf Wife’s Pride is and how to remove it).

While the barque of Senwosret is being conserved for future display, the other current major project for the science team is restoring the few coffins that museum owns—not for display, but appropriate conservation storage along with their mummies in line with CMNH’s newly adopted prohibition on the display of human remains. While a different objective than the boat’s, it is an equally important one from the standpoint of conservation ethics and the preservation of knowledge for future researchers.

As you can see above, the exhibit also touched on the conversation about reals and replicas that we’ve been having off and on here. But in this context, it’s partially to talk about restoration techniques, some of which, like we saw a couple of weeks ago with the Met’s reembedded marble fragments, involve filling in gaps in a piece. But modern conservators aren’t looking to fool people into believing a piece is more complete than it is, so they often use mending techniques like the ones for the blue faience bowl below that restore structural integrity to an object, but where the gap-filling is clearly discernible to even the untrained eye.

Speaking of faience, particularly the clay dyed that coveted turquoise blue—often simply called Egyptian Blue—the exhibition also had a station that talked about modern scientific research into discovering the methods of how the ancient Egyptians created this synthetic color. You can also see how variations in the copper content of the cuprorivaite can produce the differing shades of blue that you see in faience artifacts.

But as much as I try to promote the benefits of museums using casts and replicas (like the replica of the famous Nefertiti bust this exhibition used to illustrate pigment and materials research), I’m not insensible to the power of original objects. Something amply demonstrated by the unassuming clay vase above. There is something very humbling about looking at the marks made by the fingernails of a person who lived 4,000 years ago and they made this… that is something a mere copy can’t quite capture. But as the exhibition graphic below adds, caring for these objects is another way to connect with them; reminding us that there are many ways to find those connections and that one of the educational opportunities museums offer is to help us in the public understand those different avenues.

And that’s what a lot of the bulk of the remaining space is dedicated to—connecting us to the past and how ancient Egyptian life was in many ways not so dissimilar from ours.

So, yeah, I think The Stories We Keep does a remarkable job of making a dry, often technical, subject like conservation and making it both interesting and accessible to the public, as well as helping a small, aging, sometimes ethically fraught collection pivot toward something educationally sustainable for the 21st century. To do all of this while also dealing with the major upheaval of structural renovations is even more commendable, and I look forward to continuing glimpses into the exciting new direction of CMNH’s Egyptian collection.

Leave a comment