“So they lived, these men, in their own lusty, cheery fashion rude and rough, but honest, kindly and true. Let us thank God if we have outgrown their vices. Let us pray to God that we may ever hold their virtues. The sky may darken, and the clouds may gather, and again the day may come when Britain may have sore need of her children, on whatever shore of the sea they be found. Shall they not muster at her call?” – The White Company, chapter 37

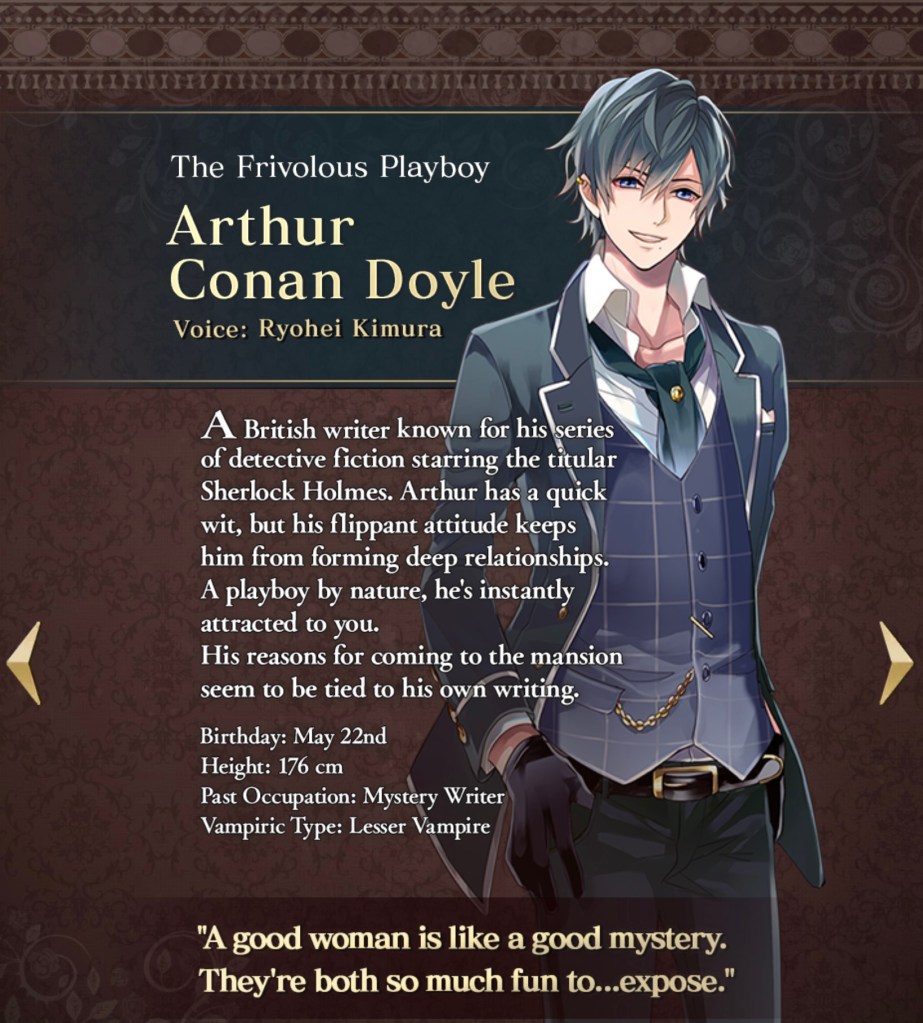

We’ve reached the time of year where I’ve met my (intentionally manageable) yearly goal on Goodreads and I’m waiting on cover finalization for The Gourd and the Stars, which pauses any editing or formatting work I could be doing. This means that I have a little extra time in a day to futz around with reading projects, the longer or more back-burner-y ones I put off at other times. As I’m still waiting for Bhishma to finish dying in the Mahabharata, I figured I’d take a break and read something I’ve been meaning to try for years: one of Arthur Conan Doyle’s historical novels. While far more famous as the creator of one of the most recognizable fictional characters in literature, Sherlock Holmes, Doyle was a passionate writer of historical fiction, and although these novels would never achieve the level of popularity of his mystery stories even at their peak, I’m always interested in examining the works a particular author is most enthusiastic about themselves.

Like many Victorians, Doyle was fascinated by the medieval period and several of his historical novels are set in this time. Because of this, and my own current preoccupation with that era, I thought this week we’d take a look at his personal favorite, The White Company, and see where the discussion takes us.

Doyle is famous enough that I hardly have to give him the exhaustive biography that many of my other author subjects have needed, but perhaps a little grounding is necessary. Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle was born in 1859 in Edinburgh, Scotland, to precariously middle class Irish Catholic parents. Although the family’s general situation spiraled for many years due to his father’s alcoholism, Doyle received an extensive private education thanks to wealthy relatives, culminating with medical studies at the University of Edinburgh. It is while in medical school that Doyle began writing on the side, in part because it was here that he met Joseph Bell, a renowned surgeon and pioneer in the field of medical forensics. Bell was already well known for his groundbreaking and meticulous scientific methodology, and it is this professor who would serve as Doyle’s model for Sherlock Holmes. Despite this early inspiration, it would be nearly a decade after he graduated that the first Holmes story, A Study in Scarlet, would appear in print in 1886. Almost instantaneously wildly popular, Doyle would be basically frog-marched by an insatiable public into writing Sherlock Holmes stories for the rest of his life, even after he’d clearly grown out of the character and had famously tried to kill off Holmes in The Final Problem.

But the Holmes stories also made Doyle wealthy enough that he could afford to occasionally write what he wanted to—when he wasn’t dabbling in architecture, sports, or spiritualism.

A man of huge international acclaim and a Renaissance man in his interests, Doyle would be almost as famous as his fictional detective by the time of his death in 1930. He had been knighted in England in 1902, as well as in Italy and the Ottoman Empire, and by the revived Knights of the Order of St. John (born out of the original medieval Hospitallers). He had written a mammoth number of works: over 200 short stories, twenty-two novels, fourteen plays, an operetta, and another twenty-some nonfiction works (well, the medical texts are nonfiction, the spiritualist stuff, erhm…). In the approaching hundred years since his death, he’s appeared as himself in nearly as many books, films, and tv shows as Holmes has. In these, he’s been a writer, a doctor, a criminal investigator—just to name a few of the hats he’s worn as a historical person turned quasi-fictional character.

But Doyle’s fictionalized afterlife is appropriate for someone who always harbored a soft spot for historical fiction, to return us to The White Company. Victorian global imperialism created a sort of temporal cultural paradox in Britain, where Englishness was both seen as the avatar of the future progress of mankind, and as the natural continuation of an unbroken historical tradition of social supremacy. This led to a 19th century revival of interest in medieval and Renaissance culture, which we’ve already mentioned in my entry about the Lambs’ Shakespeare adaptations. The Elizabethan dramatists and poets provided a pedigreed literary legacy, but it was the Arthurian myths and chivalric tales of the Middle Ages which captured the public zeitgeist. Through Arthur and his Round Table, and historic military kings like Richard I and Edward III, England could promote their foreign conquests and international position as a romantic and noble birthright (see my flavor text from TWC above, in which Doyle pretty well sums up the attitude of the era). Victorian soldiers were modern knights fighting against infidel armies like the crusaders of old, and arguably it would take the brutality of two world wars to beat that notion out of British self-conception. It would take nearly an additional century to begin to undo the academic damage this blinkered nostalgia and xenophobia would do to the field of European medieval studies.

In short, Victorian novels set in the Middle Ages were both common and popular, so it’s hardly surprising that Doyle, largely a proponent of the Empire, would have been drawn to the topic. Doyle supposedly got the idea for the story from attending a university lecture, much like Louisa May Alcott’s inspiration for her mummy fiction. But reading The White Company in our times leads a contemporary reader to unavoidable comparisons with the pre-Victorian medieval novel par excellence, Ivanhoe (1819/20), from Scotland’s other famous man of letters, Sir Walter Scott. While their settings and plot aren’t terribly similar on face, I would say that Ivanhoe and TWC share a sort of nostalgic English “flavor,” for lack of a better word. Both have this reverence for the native Saxon bloodlines of the English countryside and its ability to climb every mountain and right every wrong, something that the propagandist Middle English writer of Richard Coer de Lyon would also recognize. TWC moves forward in time from the 12th century of Ivanhoe and Richard to the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453), but the belief in Anglo-Saxon English soldiery over Frenchmen remains internally consistent.

The protagonist of TWC is a young man named Alleyne (a name Doyle would give to his son, Kingsley, as a middle name, so you can see how much he liked this one). Alleyne is the younger son of an ancient Saxon Hampshire family, whose father died when he was a baby. As a result of a stipulation in his father’s will, he was raised and educated by monks, but he is sent out of the monastic community at twenty on a kind of Catholic rumspringa to get a taste of the outside world before committing to a life in the abbey. In doing so, he has many adventures and meets many different people—the most important being Sir Nigel Loring, a renowned royal liegeman and leader of the titular White Company, fighting for England under the aegis of the famous Black Prince against the French and their allies on the Continent. The focus of the novel is on Alleyne’s bildungsroman from an intelligent and high-minded, if somewhat naive, young man into a knight, a trusted comrade, and a worthy husband to a beautiful and noble lady.

When Doyle isn’t exploring Ivanhoe-esque jousting tournaments and courtly love entanglements, the other native influence I see in much of TWC’s episodic, almost travelogue plot progression is Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, which is fitting as Chaucer himself lived through the period the novel takes place in. The main characters spend the majority of the story traveling from location to location, having both serious and comic adventures that illustrate slices of medieval life in a way that is very Chaucerian in its soul. So is Doyle’s flashes of humor, which are harder to find in the deathly-serious Ivanhoe. This is best typified by the figure of Sir Nigel himself, who, despite being a knight whose reputation is practically as high as that of the Black Prince’s on both sides of the Channel, is a short, unimpressive-looking bald man who has an almost quixotic thirst for chivalric escapades. But it also comes through in our hero, Alleyne, who is handsome and smart, but whose sheltered upbringing makes him an occasionally duped figure who must learn to cope with, as Taylor would say, the liars and the dirty, dirty cheats of the world. Not to mention that he must also learn to keep up with Sir Nigel’s beautiful and imperious daughter, Maude, if he wants to win her willful heart.

Though, I believe this episodic structure also reveals Doyle’s roots as a primarily a writer of short fiction. Much of TWC bounces along from incident to incident at a leisurely pace until Doyle gets to the last six or so chapters and he suddenly realizes that he needs to start wrapping things up. After four hundred or so pages of characterization (not necessarily unwelcome), he remembers we haven’t even met up with the White Company yet and huge chunks of the plot are breathlessly concluded in the galloping final chapter. As not a fan of long battles in novels, I’m glad that the focal historical point, the Battle of Nájera (1367), didn’t take up an inordinate amount of space, but it did sort of sneak up on you and bolt just as quickly. I don’t even mean this as a serious criticism, but more of an illustration of how difficult it is to write both novels and short stories well, and how few writers can truly pull off both wholly successfully.

To sum up, I think The White Company isn’t a great book, but in being very much a product of its age, it throws into sharper relief the sheer magnitude of Doyle’s literary achievements in his Sherlock Holmes stories. To have taken a barely-formed genre, the detective story, and single-handedly defining it for the next century is incredible. I had a perfectly cromulent time reading The White Company, but I feel I can say with confidence that while Arthur Conan Doyle could write an Ivanhoe, I don’t think Walter Scott could have written Sherlock Holmes. And that is certainly something Doyle should be proud of, if nothing else.

Leave a comment