We’re back this week with more Flight of Virtue content, and I thought I’d make good on my threat to delve into some background information on the women who make up the core supporting cast of my novel behind Theo Burr. Because while I had a blast writing a lot of the men, this was from the start a story centered on the experiences of women at this pivotal moment in history and I tried to have the narrative reflect this.

As I alluded to in some of my pre-publication posts, the place of women in Revolutionary France and post-revolutionary America was deeply paradoxical. While the revolutionary era swept away many of the earlier societal structures, the status of women in both the United States and France was largely untouched by the upheavals of the moment. Women were starting to be more systematically educated and participating in public affairs in greater numbers, but the prevailing opinion was still largely against women of respectable backgrounds having too high of a profile outside of the traditional exercises of gendered “soft power” (e.g., being a well-connected hostess, private advisor to a male family member).

Male revolutionaries in both America and France couched their ideas in the language and imagery of the Roman Republic, their model for what a non-monarchical political system could look like. They would sign off their pamphlets with pseudonyms like “Cato” and “Africanus” (the anti-Caesar, and the hero who defended republican Rome from Carthage), but this framing extended to how they interpreted the place of women in their new states. Abigail Adams signed her letters to her husband and fellow Patriots as “Portia” (the wife of Brutus), and Maximilien Robespierre called Éléonore Duplay “Cornélie” (after Cornelia Africana, the daughter of Africanus and the mother of the Gracchi). Cornelia and Portia were considered paragons of Roman womanhood in their own times, and while Cornelia exercised considerable power in her widowhood, both women were very much admired for knowing their place within Rome’s hierarchy and offering guidance from the sidelines. This is the sort of participation the Patriots and Jacobins envisioned for their wives and daughters: women educated enough to be virtuous partners to their spouses and moral mothers to a new kind of citizenry, but not for their own advancement or as equal members of society with white men.

Much as Black Americans balked at their exclusion from the liberty espoused by the republican movements of the late eighteenth century, many women—especially those whose families were the most deeply involved in revolutionary politics—chafed at these limitations that were at their heart as artificial as the monarchical structures they were dismantling. The end result was that many of these women bore the trials of these chaotic times while reaping few of the rewards for their sacrifices, sacrifices that often involved more physical and psychic damage than what their husbands, brothers, and sons suffered. Brilliant Theo’s fate was tragic, but unfortunately, her trajectory was hardly exceptional for a woman of her generation. A generation of intelligent, passionate women who had such limited scope for their talents. The more successful learned to adapt themselves both to the times and their opportunities, but many came to grief on the shoals of their imposed limitations, and it was this courageous, fatalistic streak that I wanted to celebrate in my story. So let me fill in some extra details about some of them for you.

10) Angelica Schuyler Church

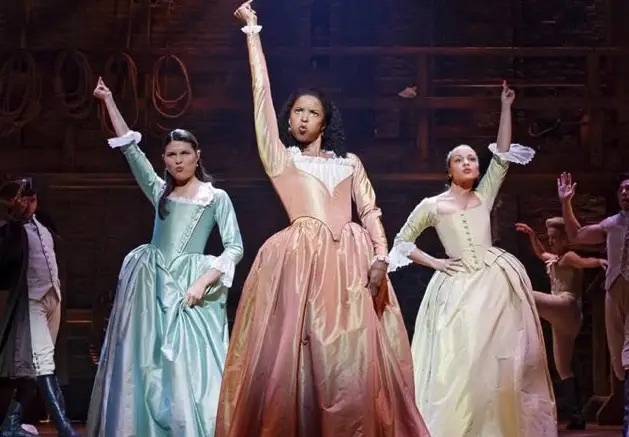

I’ll start with a minor character, but one half of America thinks they already know the score on.

Angelica Church was born in 1756, the eldest child of American Revolutionary War general Philip Schuyler. Both of her parents were descendants of old Dutch families that had been among the first to settle New York, and her father’s wealth and position in the Patriot cause made their house in Albany a major political hub during the war years where Angelica met many of the most influential men of the era. Contrary to what Lin-Manuel Miranda tried to tell all of you, Angelica was already married to her husband John Barker Church when her sister Elizabeth met Alexander Hamilton in 1780. Contemporary gossip did think that Angelica and her brother-in-law were clearly attracted to one another later, but much like Hamilton, Angelica was known for her flirtatious personality and she carried on nearly as salacious a correspondence with Thomas Jefferson as she did with Hamilton. In 1783, the Churches left New York for London, where they would live for the next sixteen years. John Church would serve in Parliament, and Angelica would run a fashionable salon that included artists, playwrights, the major English politicians of the time, and the Prince of Wales (George IV). Both Church and Angelica would be close to the marquis de Lafayette, and be involved in several of the abortive attempts to rescue him from his imprisonment in Moravia. The Churches returned permanently to the United States in 1799, where they would remain wealthy and prominent members of New York society until Angelica’s death in 1814.

Angelica’s comfortable existence and happy end was aided by her wealth and her willingness to conform to the revolutionary ideals of her time. She carried on a spirited correspondence with several important figures of the time, but ultimately, she confined her public role to being a charming hostess to her husband and a background player in politics. That said, she wasn’t entirely a conformist—Thomas Jefferson clearly enjoyed his spicy correspondence with Angelica, but probably thought she was still too forward and politically-involved to be true wife material (in his view).

9) Éléonore Duplay

Considerably less bougie than Angelica Church, Éléonore Duplay was born in 1768, the eldest child of Maurice Duplay, a Parisian cabinetmaker who became famous during the French Revolution as Maximilien Robespierre’s landlord. While hardly wealthy, the Duplays clearly aspired to middle-class status, as evidenced by Éléonore taking lessons with the painter Jean-Baptiste Regnault (the portrait of her above was done by Éléonore herself). As Robespierre’s landlords, the Duplays became deeply intertwined with Jacobin politics, and Robespierre and Éléonore seemed to have had a special bond. He called her “une âme virile,” a noble soul, and as we previously mentioned, addressed her as “Cornélie” in his letters—the ultimate compliment. How far their relationship went before Robespierre’s execution is uncertain—Éléonore’s sister, Élisabeth Le Bas, claimed they were merely “promised” to one another, while many of Robespierre’s colleagues believed her to fully be his mistress. As Catholic marriage had largely been discarded by the Revolution, it is possible that Éléonore and Robespierre had some form of secular marriage, but if this was so, Éléonore continued to use her maiden name. Either way, after his death, Éléonore wore black for the rest of her life and never married, and Paris referred to her as la Veuve Robespierre (Widow Robespierre), making the semantics of their relationship largely moot.

Éléonore was of a lower social class than most of the other women on this list, but instead of leveraging this potential advantage into a more active role in the movements of her time, her family’s aspirations for a more important position in the new social hierarchy might have made her more conservative than a higher-born woman. She played no active role in Robespierre’s public life, and was so self-effacing that many historians and writers on the period paint her as little more than a crushing fangirl. But this is a woman who spent nearly a year in prison after Robespierre’s death for no crime beyond his friendship and mourned him for the rest of her life. Her convictions might strike us as extreme, but in an age where most of the survivors of the Revolution were political chameleons, she was unusually steadfast.

8) Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, Madame Royale

Lots of long-suffering eldest kids among these ladies, and Princess Marie-Thérèse is no different. The eldest child of Louis XVI of France and Marie Antoinette, Marie-Thérèse was born in 1778, as the long-awaited heir who disappointed France by being a girl and exacerbating the underlying political problems of the country. Named for the queen’s mother, Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, Marie-Thérèse was nicknamed Mousseline by her mother, and like her younger siblings (and unlike the image of the decadent royal court), was raised far more simply than court children of the era were generally brought up. Contrary to her own maligned reputation, Marie Antoinette hated the haughty ways of her sisters-in-law and instilled in her children compassion for the less fortunate and brought peasant children to play with Marie-Thérèse. Unfortunately, it was probably too late for these conciliatory gestures from the royal family, and Marie-Thérèse would spend most of the Revolutionary decade imprisoned in the medieval Templar castle in Paris. Eventually separated from her parents and her remaining younger brother, the dauphin, Louis-Charles, she wouldn’t be informed of their fates (her parents executed, her brother dead of what we think was scrofula because of his maltreatment) until 1795, shortly before the new government agreed to release her into the care of her remaining relatives.

Marie-Thérèse was sent to join her eldest uncle, the comte de Provence, living in exile in Courland (modern Latvia), where the childless future Louis XVIII arranged a marriage between her and her cousin, the duc d’Angoulême, the eldest son of Marie-Thérèse’s other uncle, the comte d’Artois. Most of the rest of her life was spent vacillating between periods of restoration and exile as the Bourbon monarchy tried to reestablish itself during the first half of the 19th century, including the twenty minutes where Marie-Thérèse was technically queen of France between the period where Charles X (the comte d’Artois) and her husband Louis XIX jointly signed the abdication agreement forced on them by the July 1830 Revolution. Marie-Thérèse would go into a final exile, living in Britain and Prague, before dying in Austria in 1851 on the anniversary of her mother’s death.

While spared the hate her family generated during the Revolution, part of the reason the Bourbon Restorations were ultimately unsuccessful was that they, and Marie-Thérèse in particular, were understandably mistrustful of the subjects who had murdered the rest of their family. Upon her first return, there was a certain level of respect and tenderness toward her especially, but her undeniable trauma meant she could never fully reciprocate and it didn’t take long for the last Bourbon princess to be seen as cold and unfeeling, which in turn probably doomed the Restoration and left her and France at tragic crossed purposes.

7) Elizabeth Monroe

Okay, I’ll admit that I might have done Elizabeth Monroe a little dirty in FoV by making her the haughty, traditionalist foil to Theo, but some of what I depicted is historical, so let me try to make amends by sorting fact from fiction.

Elizabeth Kortright Monroe was born in 1768 to a wealthy Dutch merchant family in New York of similar social standing to the Schuylers. In 1786 at the age of seventeen, she would marry James Monroe, who was ten years her senior, and spend most of her young adult life serving alongside her husband in his various political posts, including his time as ambassador to France, governor of Virginia, and finally, president of the United States. During much of this time, Elizabeth, like Theo, experienced general ill-health, and this combined with her more standoffish personality made her less beloved than similar women in her milieu. Her reputation particularly suffered as First Lady, where she had to follow the wildly popular Dolley Madison in the role, and most people would have probably dimmed in comparison. Once Monroe’s second presidential term expired in 1825, she retreated to their property in Virginia, where she largely isolated herself until her death in 1830.

Elizabeth was in some ways a woman out of her time, where her breeding and preference for aristocratic gestures made her shunned by more democratic-leaning women of similar social standing like Angelica Church and Dolley Madison. But she should be given a lot of credit for remaining in the public eye for most of her adult life despite her many private health struggles. And it was her visit with her husband to Adrienne de Lafayette that likely pushed the National Convention to free her—an act that was personally and politically dangerous for the couple on both sides of the Atlantic. She deserves some marks for her courage for the risks she took while in France, if nothing else.

6) Thérésa Tallien

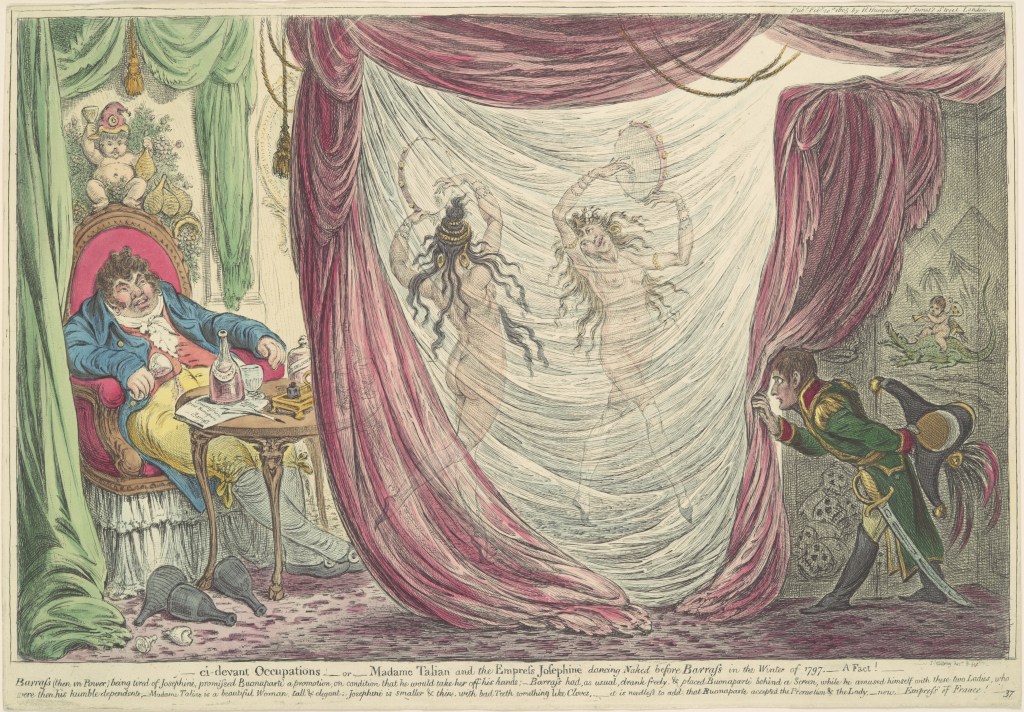

Beautiful, rich, and free-spirited, Juana María Ignacia Teresa de Cabarrús y Galabert is one of the more colorful aristocrats to survive the French Revolution. The daughter of an ennobled Basque financier and the heiress of a French industrialist, Thérésa would spend most of her life in France where she would marry the last marquis de Fontenay, divorce him after he fled the Revolution, marry the Jacobin lawyer Jean Lambert Tallien, be arrested with him on Robespierre’s command, and survive the Thermidorian Reaction to become one of the most famous social hostesses of the Empire Period. Having befriended Joséphine de Beauharnais while they were both imprisoned in Carmes prison, Thérésa and her would be the glittering lights of the post-revolutionary period, envied and infamous for their scandalous salons and even more scandalous affairs. The two women would swap Paul Barras and Napoleon between themselves, and Thérésa would divorce and marry again before dying a countess with eleven children… seven of whom were born to men she wasn’t married to.

Thérésa, as both a member of the old order and the new was a sort of bridge between the two sides of the Revolution. She’s more remembered for wild lifestyle than her intelligence or personality, and in some ways that’s a shame. She is largely responsible for originating the Greek Revival style that defined the Empire Period, and during the Thermidorian Reaction, she was a moderating influence on her husband Tallien, and by extension, the National Convention, in trying to stop the reciprocal executions, earning the nickname Notre-Dame de Thermidor (“Our Lady of Thermidor”). It might be more fun to paint her solely as the pleasure-loving woman who showed up to the Paris Opera in a transparent, sleeveless gown and no underwear—but it simplifies the creative, compassionate woman who was unafraid to live her life in a way generally reserved only for men of her time.

5) Joséphine de Beauharnais

Joséphine had a similar trajectory as her friend, Thérésa Tallien, albeit with higher highs and arguably lower lows. She was born Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie in 1763 to an aristocratic planter family on the island of Martinique, then a French colony in the West Indies. The Taschers became friendly with the mainland French des Beauharnais (very friendly, one of her aunts was her future father-in-law’s mistress) and Joséphine, then known as “Rose” to her friends, left Martinique to marry Alexandre, viscomte de Beauharnais in 1779. It was a bad marriage almost from the start, and the couple were living separately within a few years. Though this wouldn’t be enough to save Joséphine from being arrested when her husband was imprisoned for supposedly failing to adequately defend the city of Mainz with the army. He would be executed in late July of 1794, and it is likely that only the fall of Robespierre mere days later probably saved Joséphine. Thérésa Tallien got her husband to expedite Joséphine’s release, and once she was able to recover her income from Alexandre’s estate, she joined Thérésa on the salon circuit, where she met Napoleon Bonaparte, still a relatively unknown artillery officer. Within two years they were married, and in another eight, she would be crowned empress of France. But her childlessness with her new husband combined with her chronic unfaithfulness to him would eventually lead to their divorce, but she was the love of Napoleon’s life even if he wasn’t hers, and he supposedly died whispering the name we know her by—the one he gave her.

Joséphine sometimes gets a bad rap for being flighty and unromantic because she wasn’t as into Napoleon as he was into her, but like her friend Thérésa, she had come of age in brutal times where security was hard to come by. Saved from the guillotine by a hairsbreadth, she spent the rest of her life taking all that she could get, likely in an attempt to never feel that powerlessness again. I see her life and Thérésa’s as a sort of post-revolutionary memento mori—life was too short to be hemmed in by convention or what other people thought. It left Joséphine alone at her beloved mansion, Malmasion, in the end, but she’d still died an empress.

4) Anastasie and Virginie de Lafayette

The marquis de Lafayette’s daughters, Anastasie Louise Pauline and Marie Antoinette Virginie were born in 1777 and 1782, respectively. During the Revolution, the girls stayed with their mother until Adrienne was arrested after the marquis’ failed attempt to defect to Austria in 1792 and his subsequent arrest by the allied European forces of the king of Prussia and the emperor of Austria. After this, they remained under house arrest at their family seat in Auvergne until the Monroes successfully lobbied for the marquise’s release in 1795. They then traveled with Adrienne to Moravia, where their father was being held and after failing to obtain his freedom, the women stayed with him until he was finally freed in 1797. After some finagling by their mother with Napoleon, the Lafayettes were able to return to France as a family in 1799.

The interesting thing about the rest of Anastasie and Virginie’s lives after the tumultuous events of their youth, is how dead-normal they seem to have been. Both of them married suitable men of their social class, had several children, and remade their lives in the new France that followed the Revolution. Their father’s occasional, badly-received, attempts to get back into politics never seem to have affected them. Perhaps unlike Joséphine and Thérésa’s attempts to process the trauma of the revolutionary years through hedonism, the Lafayette girls retreated as far as they could into the establishment as a shield.

3) Adrienne de Lafayette

Among the women we’ve discussed here, Adrienne is probably the one most a part of the pre-revolutionary “establishment.” Born into the ancient and powerful Noailles family, she was married at fifteen to Lafayette, himself the sole heir to a rich and powerful southern French family. While an arranged marriage, the young couple were in love, even if Lafayette almost immediately bunked off to America to fight in the war there, only returning occasionally to impregnate Adrienne. Even after the end of the American Revolution, politics and the army kept the couple apart for long stretches of their marriage, culminating in their separate imprisonments during the French Revolution. As we discussed with her daughters, Adrienne spent close to five years in continuous confinement either in France or Moravia, and it soon became clear that prison conditions had taken a serious toll on Adrienne’s health. She would finally get to enjoy the quiet family life that she had always wanted, but she would die at the age of forty-eight in 1807, barely seven years after the Lafayettes’ return to France.

While fairly traditional in most senses, Adrienne is an example of a woman who perhaps was not naturally inclined to the revolutionary spirit by nature, but was able to rise with the circumstances. She adopted her husband’s ideals wholeheartedly, and when she had to fight for her family’s very lives, it was her who took the lead. She shared Lafayette’s imprisonment and it was her who convinced Napoleon to let them come home. Heroines are often made of a lot less.

2) Sally Hemings

I would love to be able to do a whole solo entry about Sally, but as I lamented in my historical note within my novel, so much of her life is unknown to us and it is dangerous to speculate too far into her mind when speaking factually (and worth extra caution when speaking fictionally). Most of what we do know about her comes from her son Madison, and he says Sarah Hemings was born in 1773 to John Wayles, a Virginia planter, and Elizabeth Hemings, an enslaved biracial woman whom he owned. Wayles died shortly after Sally’s birth and the Hemingses were inherited by her father’s white daughter Martha, who was by then married to Thomas Jefferson, which is how they were brought to Monticello.

Through some unexpected circumstances, teenaged Sally would end up accompanying her niece Mary (Polly) to join her father in Paris during Jefferson’s ambassadorship, and this is when Madison says his mother’s relationship with Jefferson began. Though it continues to be disputed by some, especially Jefferson’s white descendants, Madison’s narrative supports the DNA evidence that Jefferson was the father of Sally’s six (possibly seven) children. There are also many anecdotal contemporary stories from Jefferson’s time of Madison, and his brothers Beverly and Eston, being mistaken for Jefferson at a distance (Sally’s children had only one African great-grandmother, so all of them were more white-presenting than not).

Anyway, for motivations we can only speculate about, Sally entered into an arrangement with Jefferson that she would continue a sexual relationship with him, with the understanding that any children born to her would be freed when they turned twenty-one. Two (or three) of her children would die in infancy or childhood, but the other four would be quietly allowed to leave the plantation as they came of age. Beverly and Harriet would choose to pass as white, which they did successfully, while Madison and Eston would live as free Black men. Sally herself wasn’t freed by Jefferson’s will at his death in 1826, but Jefferson’s remaining white daughter, Martha, would choose to free her. Frankly, this would have been an inexplicable decision for a debt-ridden estate if Martha wasn’t trying to bury her father’s relationship with Sally. A free woman, Sally would move to be with Madison and Eston in Charlottesville, Virginia, where she would live until her death in 1835.

Sally’s status as an enslaved woman makes her situation fundamentally different from any of the other women in this list, as does potentially her lacuna in the historical record. But her life and her survival is only the most extreme example of the resiliency of women from this period in the face of horrific circumstances so often outside of their control.

1) Mary Wollstonecraft

And to wrap up, nothing about Mary Wollstonecraft was conventional before or after the revolutionary period. Born in 1759 to lower gentry parents, Mary would have to make her own way in the world after her violent father squandered all of their money in speculative investments. Much like the Brontës, she would spend several years doing the only kinds of work open to women of her social class—lady’s companion and governess—before throwing all of her energy into writing. She would publish several tracts on education, particularly women’s education, culminating with her most famous work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, in 1792 shortly before she traveled to France to continue her writing and be closer to the Revolution, whose ideals she agreed with. There, she became involved with American writer and entrepreneur, Gilbert Imlay, and gave birth to her first daughter, Fanny.

The rise of the Reign of Terror and the crumbling of the democratic ideals she espoused coincided with the breakdown in the radical cohabitation Mary had been living in with Imlay, and he ultimately left her stranded in a very dangerous political environment. Undeterred, Mary followed Imlay back to England, where he threw her out again, and she attempted suicide several times. It would be over a year before she could claw her way back out of her mental depression to return to her writing. Back on something of an even keel, she met the English philosopher William Godwin, who shared her political and social views, and whom she would marry when she became pregnant again in 1797. She gave birth to her second daughter, Mary (the future author of Frankenstein), but died of postpartum septicemia less than two weeks later.

If Elizabeth Monroe was a woman born too late, Mary was indubitably a woman born too early. Passionate about women’s rights and marriage equality, very few men or women were ready for her ideas. Godwin, who adored her and thought she was a genius, published her letters after her death, and this act of love would have Mary branded as a crazy whore by polite society for most of the next century and a half. The terrible irony of this period’s most brilliant feminist chasing her worthless baby daddy over half of Europe and being defeated by childbirth-related gynecological trauma before the advent of germ theory is the ultimate avatar for the place of women as a whole during this time. There was an increase of liberty, equality, and fraternity for white men in the years following the American and French Revolutions, but the accompanying “sorority” would have to wait a century or two.

Leave a comment