“One of them said we made going to the moon as exciting as taking a trip to Pittsburgh.” — Henry Hunt, Apollo 13

Now that we’re fortunate enough stateside to be (finally) enjoying a reprieve from Covid restrictions, I was able to resume my nineteen year-strong love affair with Carnegie Museums of Art and Natural History in some semblance of safety last week. Located in the heart of Pittsburgh’s historic Oakland neighborhood, these two museums share a single, conjoined structure that they also share with the main branch of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. They were conceived of and founded by industrialist Andrew Carnegie in 1895 and 1896, respectively, as a part of Carnegie’s goal of giving turn-of-the-century Pittsburgh a place in the cultural, scientific, and educational community of the United States.

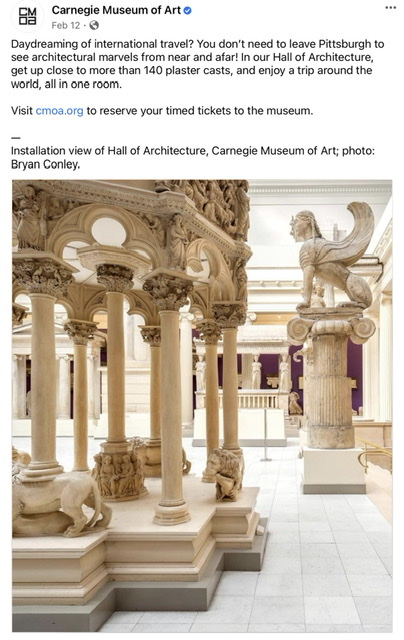

The museums straddle the border between Carnegie’s own Carnegie Mellon University and the main campus of the University of Pittsburgh, which is how, as a transplant to the city, I became familiar with them. Pitt gave their students unlimited, free access to the museums, so I spent many afternoons when I probably should have been writing papers instead flashing my student ID at the admissions desk in front of the Hall of Architecture and getting lost in the galleries. In the intervening years, I’ve had the opportunity to travel to many of the world’s great museums (I basically ran around the Louvre like I was high), but I still think of the Carnegie museums as my “home base.” Being among the relatively compact public galleries is like a comfort food; I always have this overwhelming sense of calm when I walk through their doors. How much more so after fourteen months without them except through a screen.

On the surface, neither of these museums seem like they offer much to a classical enthusiast such as yours truly, in part because Carnegie particularly wanted the art museum to be the home of the “Old Masters of tomorrow.” Indeed, the CMOA is considered perhaps the oldest modern art museum in the US. But I’ve found that digging a little deeper into the collections has yielded both fascinating information and some singular experiences along the way. As I discussed a couple of weeks ago talking about Phryne and Praxiteles, the classical world has formed the basis of everything that came after it, and Western art is both influenced by and constantly reacting against its legacy. Anyway, because they bring joy to me, I thought I’d share them with an audience that might not have any reason to travel to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to experience them firsthand.

But while not large museums on their own, together the CMOA and CMNH are expansive, so there’s more to see than one can fit into one reasonable-length blog post. Therefore we’re going to split this across a couple of posts. This week we’re going to look at what I really consider a hidden gem in the CMOA: the aforementioned Hall of Architecture, and next week, I’ll expand out to the rest of both museums to highlight some other pieces and exhibits that connect back to topics we’ve discussed here. So, let’s dive in!

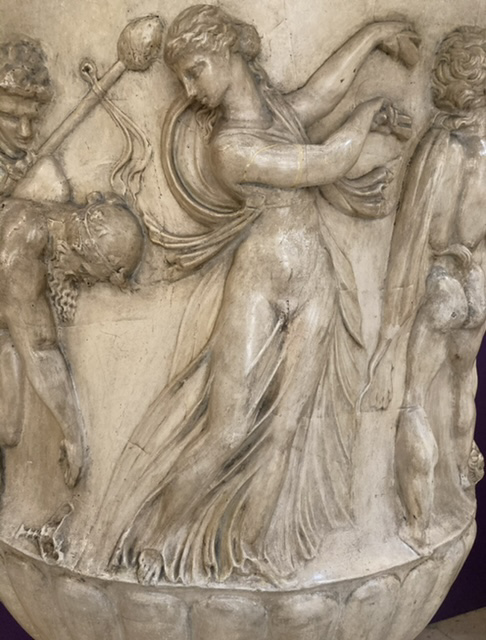

The Carnegie Museum of Art’s Hall of Architecture was added to the museum in 1907, to house over 140 plaster casts made of European and Near East antiquities acquired from professional cast companies and artisans hired to make one-time reproductions. This is largest collection of such casts in the Americas and one of the three largest in the world, superseded only by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Musée national des Monuments Français in Paris. Although a practice dating back to the Renaissance, plaster casting of antiquities reached its zenith during the 18th-19th centuries, with many major museums housing extensive plaster collections. Plaster would be added to the original, which would create a hollow mold of the piece. This mold would then be filled with more plaster and create a virtually perfect copy. The CMOA helpfully compares this to using a Jell-O mold.

Now, unlike Jell-O, plaster is inflexible, so with larger or more complicated pieces, these casts would be made in pieces that would then be reassembled like really fancy 3D puzzles. Eventually molds would be cast in gelatin, rubber, and silicone to ease this problem, but by that time the vogue for casting had started to wane.

Now, I’m sure a lot of you are thinking, “What’s the big deal, then? Who wants to look at a bunch of plaster copies of famous pieces?” Indeed, it is a sentiment shared by many people, including the many museums and institutions that have scrapped their Edwardian casts, as well as many visitors, judging by CMOA’s many cajoling social media posts trying to talk them up.

But at the time they were made, plaster casts served a vital purpose, and one I don’t think is completely absent today. Casts provided artists and scholars the opportunity to study the great artistic works of the past without the expense of traveling around the world to do so at a time where international travel was out of reach to all but the exceedingly wealthy. Indeed, that remains part of their purpose today, when a tour of the great European museums or a round-trip tour of the Mediterranean is still out of many people’s financial reach. The internet has helped to shrink the world considerably, but it is still one thing to see a picture of something and quite another to stand next to it— to be able to appreciate a sense of detail and scale.

Casts were/are also a way to spread around a finite resource. We only have a relatively small number of objects from any era, and copies can fill gaps in a museum’s collection. And before one gets too righteous about originals versus copies, remember I also told you all that any “Praxiteles” sculpture we have is itself a Greek or Roman copy. Many of the “originals” displayed by the Louvre or the British Museum are copies, too.

And in era where the post-colonial ownership of other nation’s antiquities has become a more pressing issue, copies, plaster or otherwise, might turn out to be the wave of the future. It might take time to convince the average museum goer that a “fake” is as cool to see as the real thing, but I hope to demonstrate here there is an opportunity to have different, but equally enriching experiences with both versions that museums could take advantage of, all the while fostering historical healing with nations who suffered under the imperial epoch by letting them have what belongs to them. To wit:

The Elgin Marbles are a collection of statuary originally brought to Britain from the Parthenon and the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, by Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin. The marbles have been part of one of the longest-running rightful ownership debates in the art world, with Greece demanding their repatriation since its independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1832. In fact, far from being some contemporary social justice hobbyhorse, the acquisition of the marbles was controversial in its own time as well, with many contemporary Britons, including Lord Byron, considering them stolen by Elgin under dubious Ottoman permissions. It would take a vote in Parliament for England to even agree to keep them.

But the marbles above aren’t the real Elgin Marbles— those are professional plaster casts acquired by the CMOA. Here, I’ll give you the real thing below, in a picture I took at the British Museum a few years ago:

But you might have already noticed one of the biggest differences between seeing the real marbles and the copies, which is one of the copies’ main strengths in my mind, and that’s proximity. In part because while certifiable antiques themselves at this point, the plasters aren’t priceless; and because the CMOA doesn’t have to live in fear of pissed-off repatriation activists trying to steal the marbles back like the British Museum, they can afford to let visitors get right up in the marbles’ grill. Seriously. In these pictures and the ones I’ll show you further down, I cannot stress how close to these works you are allowed to get. Virtually none of my pictures are zoomed in, and you have the ability to study the great detail in some of the most famous pieces of art in the world.

In fact, I suspect the only reason all of the CMOA’s plasters aren’t in even better shape than they are is this scandalously intimate experience they permit patrons to have. Because while there are innumerable signs reminding people not to touch the plasters, any surface within touching height bears the unmistakable trace of fingers. I think it’s a touchingly (heh) forgiving attitude on the museum’s part that they clearly know this is a constant problem, but so many of the casts remain within our grubby little grasps.

Another good example of this is the Venus de Milo. While when I saw the original at the Louvre I felt lucky enough to get an unobstructed view of her magnificence, I was still kept by her staging at a respectful distance. The CMOA’s cast of de Milo, however, is a different story.

And while her staging is less dramatic than her original perched atop a trihemiolia and the summit of a Louis XIV staircase, I can also vouch you’ll be a lot closer to the Nike of Samothrace at the CMOA than at the Louvre.

It was truly awe-inspiring to be in the presence of the original de Milo and Nike of Samothrace, but in situ, you’re also fighting crowds (and in the case of Nike, likely partially blocking a staircase) to enjoy them. As I alluded to earlier in the museum’s slightly desperate appeals, the Hall of Architecture is almost wildly unpopular— unless it’s the holiday season and they’ve set up the Neapolitan presepio(nativity) in it. On the day I was there, I wandered around taking pictures and looking at the casts for literally an hour without seeing a security guard, let alone another patron. I joke to my friends it’s my private wing of the museum, admittedly a place I enjoy for its contemplative silence as much as its art. It’s a testament to how much I believe in that art that I’m willing to let the whole internet in on what I feel is my little secret. As you can see in my pictures — on an admittedly gorgeous spring day — the space has the potential for almost transcendent lighting that can really bring the pieces to life. A few steps separate the British Museum-bound Elgins from the Louvre-housed de Milo, and another hop, skip, and a jump and you could find yourself in the bowels of the Vatican museum standing next to Rome’s grumpiest emperor.

Yes, yes, Octavius is here, too; in his most recognizable form, the Prima Porta Augustus. As you can see in full picture below, Octavius’ cast was one that was done in parts like we discussed above, with a clear break in his outstretched right arm showing how it was attached. This will make him lose some points for verisimilitude, but it is an important preservation of the casting technique.

Too late! Okay, one of the drawbacks of working in plaster as a medium is that it does break easily. But this damage can give us an inside look at the structure of these casts, too. Which is the more charitable reason not to fix it.

Shut up, Putto! Now, some of you have started to wonder why this is called the Hall of Architecture, when all I’ve showed you so far are sculptures. And this is where some of the real magic of this room comes into play, because while it’s challenging enough to want to make a perfect copy of an intricate single piece of marble, what if what you had in mind was…bigger? Like too big for the Earl of Elgin to walk off with?

This is a life-sized cast made of the south end of the Erechtheion, a temple situated on the north face of the Acropolis. This part is often referred to as the Porch of the Maidens (caryatids), the support pillars being in the shape of kore, young women. And if these girls look a little further away than some of the statues we’ve look at so far, it’s because of the porch’s scale. The base of the side is at floor level and they are commensurately far away.

The Hall of Architecture is full of facades and pillars like this. Ten foot, fifteen foot casts made of huge architectural features. The one below is an Egyptian Eighteenth Dynasty pillar that is supposed to be in the shape of a papyrus bud. The larger one to its left is a palm-column of Ramses II’s from Heracleopolis (modern Ihnasya el-Medina).

To wrap things up, I’m just going to dump a bunch of photos on you all to give you the breath of the casts in this space. As you’ll see, a lot of them are classical, but the other major focus of the museum during their acquisitions were Renaissance and Gothic cathedrals, and some of the largest casts are of church facades and vestry objects. The size and complexity of these casts are wonders unto themselves, and the artisans who made them were in many ways just as much artists as the original sculptors. While it’s doubtful plaster casting will ever regain the popularity it had a hundred years ago, I’m glad the CMOA has kept theirs as long as they have. They have their own beauty and offer a singular experience that can be just as fascinating as their venerated originals.

Leave a comment