“You’re not decorating a girl for a night on the town/ And I’m not a second-rate queen getting kicked with a crown.” – Eva Peron, Evita

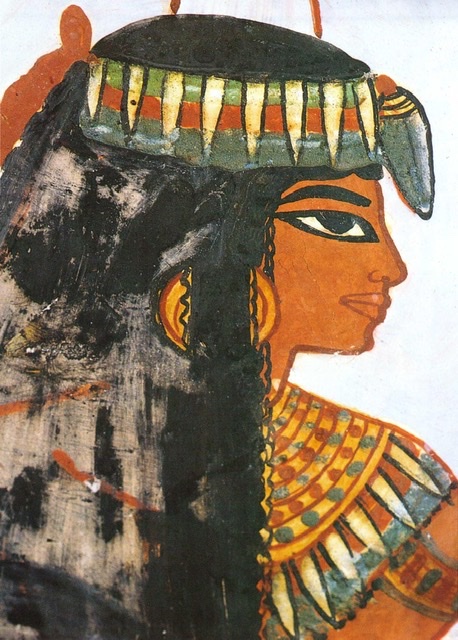

Over the summer I did an entry about clothing in the Ptolemaic/ early Roman Empire, but I thought we’d come back to personal dress again and talk about accoutrements. Because while Annie might think you’re never fully dressed without a smile, cosmetics and jewelry were as important in the ancient world as they are today. And to start us off with the Egyptian side of things, we’ll call on the Egyptian goddess of beauty herself, Hathor.

The Egyptians were unabashed fans of all manner of personal care. Cosmetics were favored by both men and women, most notably, as many of you might suspect, kohl – the black eyeliner so familiar from artistic depictions of the ta-meriu. Kohl was (and is) used extensively in many African and the Middle Eastern cultures and was traditionally made by grinding up the mineral stibnite (antimony). Like many other cultures, most notably many in India, kohl served a medical and spiritual purpose, as well as providing a beauty aid. Kohl was thought to guard the wearer from the evil eye and other witchcraft, as well as protect against eye ailments. The latter may in some way be true, as the dark eyeliner could provide some protection from sun glare in a desert kingdom, in the way that American football players will often smudge black grease paint or pre-made adhesive guards under their eyes for sunny outdoor contests.

While henna dyeing is often thought of as Indian or arriving in the Middle East through the expansion of Islam, it has much older roots of its own in Africa and Egypt. Henna was used by the Egyptians as a dye for clothing, but also in body art and nail coloring, especially for important occasions, as it is today.

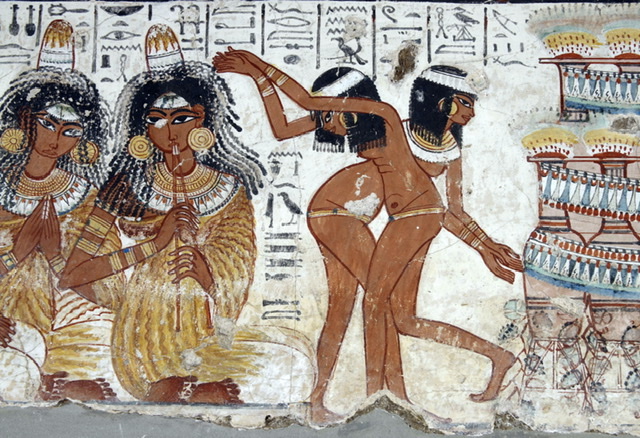

Other natural pigments were also used as eye shadows and face decoration, including frankincense, copper, malachite, and cinnamon bark were used as much for their fragrance as their deep colors. Because the Egyptians loved perfume as much as they loved makeup, admittedly a necessity in a hot climate where everyone is on the verge of being sweaty all of the time. Unlike the ancestors of some of us, the Egyptians were enthusiastic bathers and liberal appliers of fragrances. You may have wondered what those cone-shaped objects drawn on the heads of many Egyptians are, like the musicians in the picture below, and the answer is they are perfume cones. Part of any Egyptians party attire, the cones were made of soft beeswax, fats, or resin and infused with perfume. As your banquet raged into the night, the cone would slowly melt into your hair and over your person, giving your perfume a pick-me-up hours after you’d left your house.

Now when I say, “your hair”, for an Egyptian, that’s not strictly accurate. Your hair would be something you owned, rather than something you grew yourself. In addition to their high hygiene standards, Egyptians abhorred all body hair, including the stuff on the top of your head. Hair removal was typically achieved with pumice stones or sharpened shells used like razors. An exception to this were children, who generally wore a lock of hair plaited on one side of their head until they were of age, called the sidelock of youth.

Now, some of this attitude toward body hair was likely practical, again given the temperature of their environment, but obviously that wasn’t the whole story, in light of their obsession with wigs. Because while Egyptians weren’t particularly fond of natural hair, they appreciated hair beauty. Indeed, one of the defining attributes of Hathor’s celestial attractiveness was her beautiful hair.

Anyway, wigs came in a variety of styles, the cost of which was tied to length and the elaborateness of the hair plaiting. Because when you see an Egyptian woman with long, flowing hair in their pictorial art, that hair is actually hundreds of tiny braids which required master craftsmanship and upkeep. Sometimes stone and statuary work give one a better feel for this.

While, as we talked about before, the linen shifts of all sexes and most ranks were relatively plain aside from pleat-work, one suspects that clothing was used as a backdrop for the Egyptians’ first love: jewelry.

Jewelry was worn by everyone, and while fads would come and go, there were a number of staples that would stick through the dynasties, continuing into the Ptolemaic era. Earrings could be studs or dangling, the latter more likely to be a women’s style, and bracelets/ anklets either as bangles or cuffs. Rings were common, with gems, cut glass, or signet-style. Belts and girdles were also common, and indeed, is usually the only clothing item worn by children or certain artistic performers (see the pictures above).

But like the kohl, what most people think of when they think of Egyptian jewelry is the jaw-dropping broad collar or pectoral necklaces. We often visualize the impressive gold and glitter affair in the first picture below, but broad collars could also be made of simpler materials, like the second necklace made of linen and faience, a fired pottery, often in that distinctive Egyptian blue-turquoise.

The Egyptians favored gold as their metal medium of choice, for its malleability, and gemstones were obviously coveted, but some of the most stunning pieces of jewelry we’ve recovered make expert use of glass, resin, and enamel as well. Materials were of course based on availability, but also many metals and stones had special religious significance and were chosen to shield the wearer from malignant forces. Amulets for this purpose were also perennially popular, with Horus’ wadjet; the god Ptah’s symbol, the djed; and the god Bes as favorite choices.

Now, the Romans weren’t strangers to cosmetics and personal care, but their attitude was a little more ambivalent, especially along gender lines. Men were expected to be well-groomed, but what we would have dubbed metrosexuality in the 2000s was considered effeminate and beneath the dignity of a Roman man. In part because men who wore a lot of makeup or jewelry were associated with Rome’s “barbarian” enemies, like the Egyptians and Persians. Because the overwhelming majority of Roman writers were men, we have ample evidence of the red-blooded Roman’s disdain for both the makeup-wearing man and Roman women for wearing too much, not enough, and swearing by ancient nighttime chemical peels that smelled horrific. But women’s use of cosmetics did have one champion among the literary set.

Ovid is generally fully on board with cosmetic use by Roman ladies; he even wrote a didactic elegy about it – the Medicamina Faciei Femineae. The poem, a tongue-in-cheek parody of Virgil’s sober agricultural manual, the Georgics, is a how-to guide for Roman skincare. And despite the unserious tone (and its author), the Medicamina contains legitimate home remedies using natural ingredients like barley, egg, gum Arabic, and honey; unlike Roman historian Pliny the Elder’s facial remedies, whose ingredients are frequently poisonous or just plain gross.

As Ovid just implied, smooth complexions were prized by the Romans as they are generally now. Women chased after paler skin tones, the mark of a lady of leisure who didn’t have to attend to outdoor work, and also as a sign of purity and chastity. Men, conversely, were expected to be tanner, to show they led active, outdoorsy lives. But, as many of your acquaintances of Italian descent will tell you, few Roman women possessed naturally pale skin tones, so cream and powder usage were rampant. In addition to the ingredients Ovid listed in his Medicamina, women would use oils and resins infused with frankincense, onions, ground oyster shells, and sheep’s urine to bleach their faces, as well as the white lead-based and chalk cosmetics that would continue to be utilized into the modern era. Cleopatra swore by ass-milk (as in donkey milk, don’t be extra disgusting) baths that were supposed to have miraculous skin-smoothing properties.

Despite this focus on being ghost-white wraiths, Roman women also used rouge for a healthy-looking glow, but as today, Roman men were always quick to point out when women were wearing too much. Rouge was made of safer ingredients like vermillion and poppy petals, but like the white lead face creams, red lead and poisonous cinnabar were used extensively. And despite what you might suppose, the Romans were already well aware that lead was unsafe, but as with many fashions, sometimes the results meant people were willing to die for it.

Roman women used much of the same eye makeup as their Egyptian counterparts, favoring greens (ground malachite) and blues (ground azurite). Roman beauty was focused on large eyes with long, dark lashes, so women also used kohl to enlarge the appearance of their eyes, and soot or antimony to darken their eyebrows. It is possible women used red dyes from India to color their nails, but there is little evidence of lipstick in the Latin world. The one thing both Roman men and women could agree on was a love of perfume and fragrance – rose, iris, and honey being popular scents.

For all of these cosmetics, just like today, there were expensive designer brands favored by the wealthy and hordes of cheap knockoffs that the average woman could afford. Roman men might want to restrict makeup usage exclusively to prostitutes, but virtually all women (and more men than they’d have you believe) used some kind of cosmetics in their daily life. The only women specifically forbidden to wear any were the Vestal virgins, as a sign of their virtue and literal chastity.

While not as fanatical about hair removal as the Egyptians, Roman women plucked and removed excess hair in much the same way, save for the head shaving. Resin preparations were used like waxing, or hair was worked off with a pumice stone. During the period of time we’re discussing, Roman men were typically clean-shaven, but that would slowly change as the empire expanded and beards would eventually be en vogue.

Octavius and the Roman writers moaning for the simple and heroic past might also want to restrict women to very plain hairstyles of simple buns and knots, but that wouldn’t last for very long. Roman women were adept at using curling irons, hairpieces, and wigs to sculpt their coifs into nearly every shape you can imagine. Below are a few examples of the ladies Augusti advertising their modesty with their understated ‘dos, and then some more daring examples from their friends and the women of the later empire.

Ovid writes a very funny poem on this subject to his muse, Corinna, who suffers an embarrassing mishap while trying to emulate the latest elaborate hairstyle:

“…You decided on corkscrew ringlets. The irons were heated, / Your poor hair crimped and racked/ Into spiraling curls. ‘It’s a crime,’ I told you, ‘a downright/ Crime to singe it like that. Why on earth/ Can’t you leave well alone? You’ll wreck it, you obstinate creature,/ It’s not for burning… gone, all gone… Poor sweet — she’s shielding her face to hide those ladylike/ Blushes, and making a brave effort not to cry/ As she stares at the ruined hair in her lap, a keepsake/ Unhappily out of place. Don’t worry, love,/ Just put on your makeup. This loss is by no means irreparable—/ Give it time, and your hair will grow back as good as new.”

Beautiful hair pins and nets were often used by upper class Roman women, as were various tiaras and diadems. But simple cloth and silk bands were also prevalent, each style lending itself to one or the other.

Jewelry was also a somewhat more understated affair in Rome, at least compared to Egypt. Although Romans would also wear jewelry to ward off the evil eye, they were arguably more indiscriminate in their materials, using gold and silver, but also bone, bronze, and pearls. Like with cosmetics, women where the dominant wearers, though Roman men would wear rings. Roman women would wear necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and rings, the design of which are often very similar to we might wear today.

But one of the biggest uses of jewelry display for both sexes were their fibulae, the brooches and pins that fastened one’s tunica, stola, or toga together. Fibulae might be very simple, or incredibly intricate, as the examples below show.

And there you have it, a brief look at putting on the finishing touches on your outfit in the 1stcentury BC/ AD. Unlike wearing togas and kilts, this part of ancient living feels very familiar: people following the latest trends, social critics bemoaning the corruption of virtue through makeup and crazy hairstyles, all of it sounds like every Buzzfeed think piece you’ve ever read. So, don’t fret over the next fad that comes your way, because this is one part of the human condition where plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Leave a comment